|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2020;57: 1119-1123 |

|

Effect of Umbilical Cord Milking vs

Delayed Cord Clamping on Venous Hematocrit at 48 Hours in

Late Preterm and Term Neonates: A Randomized Controlled Trial

|

|

Mukul Kumar Mangla, Anu Thukral, M Jeeva Sankar, Ramesh

Agarwal, Ashok K Deorari and VK Paul

From Division of Neonatology, Department of Pediatrics,

All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Anu Thukral, Assistant Professor,

Department of Pediatrics, Newborn Health and Knowledge

Centre,

First Floor, New Private Ward, AIIMS, New Delhi 110 029,

India.

Email:

[email protected]

Received: November 03, 2019;

Initial review: January 20, 2020;

Accepted: September 08, 2020.

Trial Registration: CTRI/2016/11/007470

Published online: September 16, 2020;

PII: S097475591600248

|

|

Objective: To compare the effect of intact umbilical cord

milking (MUC) and delayed cord clamping (DCC) on venous

hematocrit at 48 (±6) hours in late preterm and term neonates

(350/7- 426/7 wk).

Study Design:

Randomized trial.

Setting and participants:

All late preterm and term neonates (350/7 - 426/7 wk) neonates

born in the labor room and maternity operation theatre of

tertiary care unit were included.

Intervention: We

randomly allocated enrolled neonates to MUC group (cord milked

four times towards the baby while being attached to the

placenta; n=72) or DCC group (cord clamped after 60

seconds; n=72).

Outcome: Primary

outcome was venous hematocrit at 48 (±6) hours of life.

Additional outcomes were venous hematocrit at 48 (±6) hours in

newborns delivered through lower segment caesarean section

(LSCS), incidence of polycythemia requiring partial exchange

transfusion, incidence of hyperbilirubinemia requiring

phototherapy, and venous hematocrit and serum ferritin levels at

6 (±1) weeks of age.

Results: The mean

(SD) hematocrit at 48 (±6) hours in the MUC group was higher

than in DCC group [57.7 (4.3) vs. 55.9 (4.4); P=0.002].

Venous hematocrit at 6 (±1) weeks was higher in MUC than in DCC

group [mean (SD), 37.7 (4.3) vs. 36 (3.4); mean

difference 1.75 (95% CI 0.53 to 2.9); P=0.005]. Other

parameters were similar in the two groups.

Conclusion: MUC leads

to a higher venous hematocrit at 48 (±6) hours in late preterm

and term neonates when compared with DCC.

Keywords: Anemia, Infant,

Placental redistribution, Transfusion.

|

P

lacental

transfusion provides sufficient iron reserves for the first

3 to 6 months of life; thus, preventing or delaying the

development of iron deficiency until the use of

iron-fortified foods is implemented [4]. Delayed cord

clamping (defined variably as clamping till cessation of

pulsations or up to 60-180 seconds) leads to improvement in

levels of hemo-globin and hematocrit at two months of age

[5]. However, universal application is limited in particular

due to obstetrician concerns for the risk of hypothermia,

and delay in initiation of resuscitation, when indicated

[6,7].

Umbilical cord milking, on the other

hand, involves milking the entire contents of the umbilical

cord towards the baby. Cut umbilical cord milking (umbilical

cord detached from placenta) limits the refilling of cord

from placenta, so less blood is likely to be transfused when

compared to intact umbilical cord milking (pushing the blood

toward the infant at least four times before clamping the

umbilical cord) [8-12].

Till date, two studies [13,14] have

evaluated the effect of delayed cord clamping and umbilical

cord milking in term neonates. In both studies, cut

umbilical cord milking was performed. Hence, we planned the

present study to evaluate the effect of intact umbilical

cord milking on venous hematocrit at 48 hours of age in late

preterm and term neonates when compared with delayed cord

clamping.

METHODS

This open labelled randomized trial was

conducted in the department of obstetrics and gynecology,

All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi from May

to September, 2016. All late preterm and term neonates (35 0/7

- 426/7 week)

were included in the study. Neonates with fetal hydrops,

major congenital malformation, Rh isoimmunization (Rh

positive neonate born to Rh negative mother with indirect

Coombs test (ICT) positive) [15], newborns born through

meconium stained liquor who were non-vigorous at birth

(defined by poor/no respiratory efforts, weak/no muscle tone

and heart rate less than 100 beats per minute, limp or

apneic or poor tone at birth) [16], forceps or vacuum

assisted delivery, and newborns born to HIV positive mother

(on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) followed by

Western blot test for HIV) and maternal eclampsia (defined

as generalized seizure in pregnant females with

preeclampsia) [17] were excluded from the study. The study was

approved by the institutional ethics committee.

All eligible mothers admitted in the

labor room were screened for eligibility and enrolled, after

informed written consent. We allocated mothers using

computer generated random sequence to intact umbilical cord

milking group and delayed cord clamping group. Opaque

envelopes containing allocation group were serially

numbered, and sealed to conceal the identity. The sealed

envelope was opened by the nursing staff when the expectant

mother was wheeled inside the labor room. The intervention

written on slip was carried out by the obstetrics and

gynecology resident and pediatric resident team posted in

the labor room. Blinding of the clinicians was not possible

due to the obvious nature of intervention.

Intact umbilical cord milking (MUC) group:

The intact umbilical cord for its remaining accessible

length (nearly half of the total length) was milked four

times towards the baby by the residents on duty in the

obstetrics department, and then clamped. All the health

care providers (postgraduate residents of pediatrics and

obstetrics) were trained in a structured manner for intact

umbilical cord milking.

Delayed cord clamping (DCC) group:

Umbilical cord was clamped at least 60 seconds from the

time of delivery.

Time of all interventions was recorded by

a stopwatch and noted in the study form. In both the groups,

the baby was held at introitus after vaginal delivery, and

over mother’s thigh in caesarean delivery. After delivery,

the babies were kept with mothers unless they required

admission in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) for

standard indications. Gestational age was assigned based on

the last menstrual period. The appropriateness of

birthweight for gestational age was assigned by stan-dard

intrauterine growth chart [18]; weight less than 10th

centile and weight more than 90th centile being adjudged as

small for gestational age (SGA) and large for gestatio-nal

age (LGA), respectively [18]. Early breastfeeding was

encouraged in all babies as per standard guidelines. The

infants were evaluated at birth, and at the age of 24 hours

and then at 48 hours.

The primary outcome was venous hematocrit

evaluated at 48 (±6) hours. Additional outcomes were venous

hematocrit at 48 (±6) hours in newborns delivered by lower

segment caesarean section (LSCS), incidence of polycythemia

(defined as venous hematocrit greater than 65% at 48 (±6)

hours of life) [19] requiring partial exchange (PET),

incidence of hyperbilirubinemia requiring photo-therapy (as

per American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) charts) [20],

venous hematocrit at 6 (±1) weeks, and levels of serum

ferritin at 6 (±1) weeks.

Venous sample was collected in micro-

capillaries for measurement of hematocrit, and an additional

1 mL sample was separately collected for serum ferritin

levels. Micro-capillaries were micro-centrifuged at a speed

of 9000 rpm for 5 minutes and analyzed with card reader for

hematocrit measurement. Serum bilirubin was assessed in

babies with clinical icterus by spectrophotometer (Apel BR

5100, APEL). Calibration of the spectrophotometer was done

at defined intervals, as recommended by the manufacturer and

phototherapy was instituted, if required. Serum ferritin

levels were evaluated with ELISA orgentech kit (analytical

sensitivity, 5 ng/mL; range of evaluated concentrations

5-1000 ng/mL).

Attendants were counseled by the

principal investi-gator to follow up at 6 (±1) weeks, which

coincided with their immunization visit. Hematocrit

evaluation and serum ferritin levels were evaluated at this

time point. On follow up, parents were asked about any

intercurrent illnesses since birth, and type and mode of

feeding (top fed, exclusively breastfed or predominantly

breastfed.

Venous hematocrit at 48 (±6) hours in a

previous study was 50% [10]. Anticipating that intact

umbilical cord milking will lead to at least a 5% absolute

increase in the hematocrit and assuming a standard deviation

(SD) of 7 in each group with power of 90% and alpha of 0.05,

we needed to enroll at least 42 neonates in each arm.

Considering an attrition rate of 40% on follow up, total

sample size was increased to 72 in each group.

Statistical analyses:

Statistical analyses were performed with Stata 11 (Stata

Corp LP). Baseline categorical variables were compared using

Chi-square or Fisher exact test, as appropriate, and whereas

continuous variables were compared using Student t-test. A

P-value of less than 0.05 was considered as significant. The

analysis was by the intention to treat.

RESULTS

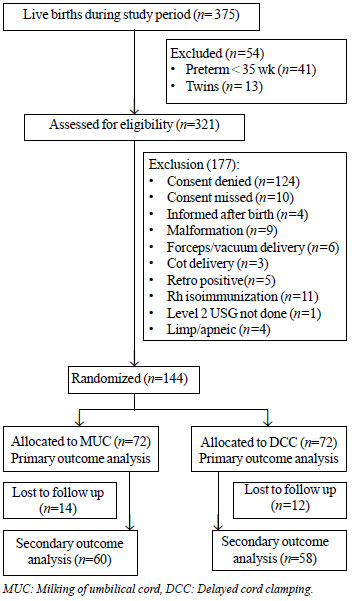

A total of 375 babies were delivered

during the enrolment period, of which 144 babies fulfilled

the inclusion criteria and were enrolled (Fig. 1).

Baseline characteristics including maternal pregnancy

induced hypertension, gestational diabetes, gestational age

and birthweight were comparable between the two groups (Table

I). 72 neonates were enrolled to DCC and 72 neonates to

MUC group. Out of the 144 neonates, 118 (82%) completed the

trial at 6 (±1) weeks. There were no adverse events in

either group during the study period.

|

|

Fig. 1

Study flow chart.

|

Table I Baseline Maternal and Neonatal Characteristics of the Two Groups

|

Umbilical cord

|

Delayed cord

|

|

|

milking group |

clamping group |

|

(n=72) |

(n=72) |

|

Maternal characteristics |

|

|

|

Booked pregnancy |

72 (100) |

71 (99) |

|

Maternal age (y)* |

29.1 (4.2) |

28.3 (3.3) |

|

Lower segment caesarean section

|

31 (43) |

36 (50) |

|

Hemoglobin (g/dL)* |

11.7 (1.2) |

11.4 (1.1) |

|

Chronic hypertension |

7 (9.7) |

4 (5.5) |

|

Pregnancy induced hypertension |

3 (4.1) |

3 (4.1) |

|

Meconium stained liquor |

2 (2.7) |

6 (8.3) |

|

Intra uterine growth retardation |

1 (1.4) |

3 (4.1) |

|

Gestational diabetes mellitus |

13 (18.1) |

11 (15.2) |

|

Neonatal characteristics |

|

|

|

Gestation age (wk)* |

37.9 (1.0) |

37.8 (1.6) |

|

Male sex |

36 (50) |

36 (50) |

|

Small for date

|

1 (1.4) |

0 |

|

Large for date

|

10 (13.9) |

9 (12.5) |

|

Weight (g)* |

3038 (436) |

2909 (435) |

|

Use of any respiratory support |

3 (4.1) |

3 (4.1) |

|

Admission in NICU |

1 (1.4) |

2 (2.8) |

|

Time since cord clamp (s)*# |

12.9 (0.8) |

60 (0) |

|

Data depicted as n (%) or *mean (SD); All

P<0.05 except #P<0.01. |

The mean (SD) hematocrit at 48 (±6) hours

in the MUC group [57.7 (4.3)] was significantly higher than

the DCC group [55.9 (4.4)] [mean difference (MD)

1.7 (95% CI 0.21 to 3.1); P=0.002] (Table

II). Venous hematocrit in newborn delivered by caesarean

section at 48 (±6) hours was similar in the two groups.

Incidence of polycythemia was also similar in the two

groups. One neonate in each group required phototherapy.

Mean (SD) Venous hematocrit at 6 (±1) weeks was higher in

MUC than in DCC group [MD (95% CI) 1.75 (0.53 to 2.9); P=

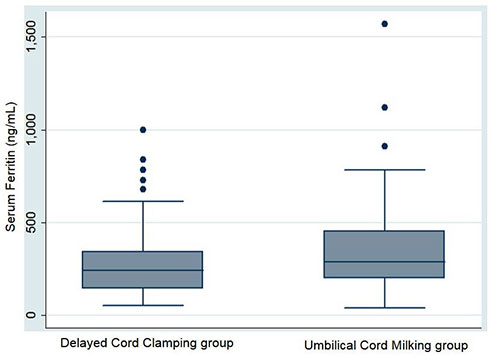

0.005] (Table II). The levels of serum

ferritin were similar in the two groups (Table II

and Fig. 2).

Table II Primary and Secondary Outcome Variables in Late Preterm and Term Neonates in the Study

|

Parameter |

MUC group

|

DCC group |

Mean

|

|

(n=72) |

(n=72) |

difference |

|

|

|

(95% CI) |

|

Hematocrit at 48 (±6) h |

57.7

|

55.9

|

1.68

|

|

|

(4.3) |

(4.4) |

(0.21, 3.1) |

|

Secondary outcomes |

(n = 58) |

(n = 60) |

|

|

Hematocrit# |

37.7

|

36 9

|

1.7

|

|

(3.3) |

(3.4) |

(0.53, 2.9) |

|

Serum ferritin (ng/mL)# |

363.1 |

295.8 |

67.2

|

|

|

|

(-24.0, 158.5) |

|

Hyperbilirubinemia*

|

1 (1.4) |

1 (1.4) |

- |

|

Polycythemia^ |

0 |

2 (2.8) |

- |

|

Hematocrit at 48 (±6) h‡

|

57.4

|

56.4

|

1.02

|

|

|

(4.4) |

(4.8) |

(-1.2, 3.2) |

|

*Requiring phototherapy; #at 6 (±1) wk;

^requiring partial exchange transfusion; ‡Newborns

delivered by lower segment caesarean section,

n=31 in UCC and 36 in DCC group. |

|

|

Fig. 2 Box-and-whisker

plot for serum ferritin at 6 (±1) weeks in neonates

in the delayed cord clamping and umbilical cords

milking groups.

|

DISCUSSION

This randomized trial compared intact

umbilical cord milking (MUC) with delayed cord clamping

(DCC) on venous hematocrit at 48 (±6) hours of life in late

preterm and term neonates. The hematocrit at 48 (±6) hours

and at 6 (±1) week was higher in the intact MUC group.

However, it was similar in the two groups in infants

delivered by LSCS. Other parameters including incidence of

polycythemia, incidence of hyperbiliru-binemia requiring

phototherapy and ferritin were similar in the two groups.

There are very few studies in late

preterm and term infants comparing MUC with DCC. Jaiswal,

et al. [13] evaluated the effect of MUC and DCC on

hematological parameters (serum ferritin and hemoglobin) at

6 (±1) weeks of life in term neonates. The packed cell

volume (PCV) at 48 (±6) hours and hemoglobin level at 6 (±1)

weeks postnatal age was similar in the two groups in

contrast to the results of the present study. Studies in

preterm infants comparing DCC suggest mixed results

[8,9,11,12]. The

cord vein contains nearly 20 mL of placental blood and

one-time umbilical cord milking (of cut segment of about 30

cm) can transfer nearly 18 mL/kg of blood to the newborn

[9,21,22]. The newborn is likely to get more blood if the

cord segment is intact, since this allows subsequent

refilling of cord from placenta explaining the higher

hematocrit at 48 (±6) hours and higher hemoglobin at 6 (±1)

weeks seen in the present study.

We observed no difference in the

hematocrit in MUC and DCC group in neonates delivered by

LSCS. A recent study by Katheria, et al. [11] in

preterm neonates delivered by cesarean delivery suggested a

higher hemoglobin (within the first 24 hours) in MUC group.

Infants delivered by cesarean section have a lower

circulating red cell volume due to the anesthetic and

surgical interventions which interfere with active uterine

contraction, thus leading to more blood volume remaining in

placenta and hence a lower hematocrit

[22]. However, we did not evaluate the

hematocrit at birth or within 24 hours.

We did not observe any difference in the

incidence of hyperbilirubinemia requiring phototherapy or

the incidence of polycythemia at 48 (±6) or any difference

in serum ferritin at 6 (±1) weeks. These findings have been

previously reported [8,9,12,16].

Our study is the first study in late

preterm and term neonates where intact umbilical cord

milking (milking done with umbilical cord attached to

placenta) was compared to delayed cord clamping for

evaluation of hematological parameters. This trial ensured

appropriate allocation concealment. The outcome assessors

and laboratory team were blinded to the intervention arm. We

had a follow up rate of 82%. Our study had some limitations

too. A longer follow-up till at least 6 to 12 months is

desirable to establish whether the initial advantage in

hematocrit also translates into gains in infancy and early

childhood, which we did not plan.

Umbilical cord milking leads to higher

venous hematocrit at 48 (±6) hours when compared with

delayed cord clamping in late preterm and term neonates,

however long-term effects of milking need to be further

evaluated.

Ethics clearance: Institute Ethics

Committee, AIIMS; No. IECPG/197/24.02.2016, RT-10, dated

March 30, 2016.

Contributors: MKM: protocol

development, study implementation, data management and

writing the manuscript; AT, MJS: development of the protocol

and supervised implementation of the study and contributed

to writing of the manuscript and did data analysis; VKP,

AKD, RA: protocol development, and provided critical inputs

in manuscript writing. All authors approved the final

version of manuscript, and are accountable for all aspects

related to the study.

Funding: None; Competing

interests: None stated.

|

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN?

•

Delayed cord

clamping leads to improvement in levels of

hemoglobin and hematocrit at two months of age.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS?

•

Umbilical cord milking leads to higher venous

hematocrit at 48 (±6) hours when compared with

delayed cord clamping in late preterm and term

neonates

•

Intact cord milking does not result in neonatal

hyperbilirubinemia or symptomatic polycythemia as

compared to delayed cord clamping.

|

REFERENCES

1. Lozoff B. Iron and learning potential

in childhood. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1989;65:1050-66.

2. Stevens GA, Finucane MM, De-Regil LM,

et al. Global, regional and national trends in

hemoglobin concentration and pre-valence of total and severe

anemia in children and pregnant and non-pregnant women for

1995-2011: A systemic analysis of population representative

data. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1:e16-e25.

3. International Institute for Population

Sciences (IIPS) and Macro International. 2007. National

Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005–06: India: Volume I.

IIPS. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FRIND3/FRIND3-Vol1AndVol2.pdf.

Accessed Jan 10, 2018.

4. WHO. Guideline: Delayed Umbilical Cord

Clamping for Improved Maternal and Infant Health and

Nutrition Outcomes. World Health Organization; 2014.

Available from: https:

www.who.int/nutrition/publications/guide lines/cord_clamping/eng.pdf.

Accessed January 10th 2018.

5. Beyond survival: integrated delivery

care practices for long-term maternal and infant nutrition,

health and development. II ed. PAHO, 2013. Available from:

https://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/Beyond

Survival2ndeditionen.pdf?ua=1. Accessed Jan 20, 2018.

6. Jelin AC, Kuppermann M, Erickson K,

et al. Obstetricians’ attitudes and beliefs regarding

umbilical cord clamping. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med.

2014;27:1457-61.

7. Boere I, Smit M, Roest AA, et al.

Current practice of cord clamping in the Netherlands: a

questionnaire study. Neonatology. 2015; 107:50-5.

8. Hosono S, Mugishima H, Fujita, et

al. Umbilical cord milking reduces the need for red cell

transfusions and improves neonatal adaptation in infants

born at less than 29 weeks’ gestation: A randomized

controlled trial. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed.

2008;93:F14-9.

9. Rabe H, Jewison A, Alvarez RF, et

al. Milking compared with delayed cord clamping to

increase placental transfusion in preterm neonates: A

randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol.

2011;117:205-11.

10. Owen DA, Mercer JS, Oh W. Umbilical

cord milking in term infants delivered by caesarean section:

A randomized controlled trial. J Perinatol. 2012;32:580-84.

11. Katheria AC, Truong G, Cousins L,

Oshiro B, Finer NN. Umbilical cord milking versus delayed

cord clamping in preterm infants. Pediatrics.

2015;136:61-69.

12. Shirk S, Manolis S, Lambers D, Smith

K. Delayed clamping vs. milking of umbilical cord in

preterm infants: A randomized control trial. Am J Obstet

Gynecol, 2019; 220:e1-8.

13. Jaiswal P, A Upadhyay, Gothwal S,

et al. Comparison of two types of intervention to

enhance placental redistribution in term infants:

Rando-mized control trial. Eur J Pediatr. 2015;17:1159-67.

14. Yadav AK, Upadhyay A, Gothwal S,

Dubey K, Mandal U, Yadav C. Comparison of three types of

intervention to enhance placental redistribution in term

newborns: Randomized control trial. J Perinatol.

2015;35:720-24.

15. Moise KJ. Management of rhesus

isoimmunization in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol: 2008;

112:164-76.

16. Weiner GM, Zaichkin J. Textbook of

neonatal resusci-tation.7th edition: American Academy of

Pediatrics; 2016.p.12.

17. Fauvel JP. Hypertension during

pregnancy: Epidemiology, definition. Presse Med.

2016;45:618-21.

18. Singhal PK, Paul VK, Deorari AK,

Singh M, Sunderam KR. Changing trends in intrauterine growth

curves. Indian Pediatr. 1991;28:281-83.

19. Ramamurthy RS, Brans WY. Neonatal

polycythemia. Criteria for diagnosis and treatment.

Pediatrics. 1980;97:118-20.

20. American Academy of Pediatrics

Subcommittee on Hyperbilirubinemia: Management of

Hyperbilirubinemia in the Newborn Infant 35 or More Weeks of

Gestation. Pediatrics. 2004;114:297-316.

21. Blood. In: Haneef SM, Maqbool

S, Arif MA, eds. Text book of Paediatrics.

International Book Bank; 2004.p.545.

22. Aladangady N, McHugh S, Aitchison TC, Wardrop CA,

Holland BM. Infant’s blood volume in a controlled trial of

placental transfusion at preterm delivery. Pediatrics.

2006;117:93-8.

|

|

|

|

|