|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2018;55:1075-1082 |

|

Congenital

Heart Disease in India: A Status Report

|

|

Anita Saxena

From the Department of Cardiology, All India

Institute of Medical Sciences,

New Delhi 110 029, India.

Email: [email protected]

|

Considering a birth prevalence of congenital heart disease as 9/1000,

the estimated number of children born with congenital heart disease in

India is more than 200,000 per year. Of these, about one-fifth are

likely to have serious defect, requiring an intervention in the first

year of life. Currently advanced cardiac care is available to only a

minority of such children. A number of cardiac centers have been

developed over the last 10 years. However, most are in the private

sector, and are not geographically well-distributed. Challenges to

pediatric cardiac care include financial constraints, health-seeking

behavior of community, and lack of awareness. Government of India is

taking a number of steps for improving health of children through its

various program and schemes that are likely to benefit children with

congenital heart disease, especially those who are vulnerable and

marginalized.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Birth defects, Congenital heart

defects, Echocardiography.

|

|

C

ongenital heart disease (CHD) is the most

frequently occurring congenital disorder, responsible for 28% of all

congenital birth defects [1]. The birth prevalence of CHD is reported to

be 8-12/1000 live births [2,3]. Considering a rate of 9/1000, about 1.35

million babies are born with CHD each year globally [4].

With rapid advances in diagnosis and treatment of

CHD, vast majority of children born with CHD in high-income countries

reach adulthood. However, this is not the case for children born in low-

and middle-income countries (LMIC) as such advanced care is not

available for all children. Considering a birth prevalence as 9/1000,

the estimated number of children born with CHD every year in India

approximates 240,000, posing a tremendous challenge for the families,

society and health care system. This article discusses the current state

of cardiac care available to children with CHD and how it has changed

over last decade [5].

Epidemiology

The birth prevalence of severe CHD has been

consistently reported as 1.5 - 1.7/1000 live births [3,6,7]. Use of

echocardiography is associated with higher birth prevalence as many

milder cases are also detected [6-8]. Similarly, hospital-based data is

unlikely to be representative of community prevalence in LMIC where a

substantial proportion of births occur at home. Critical CHD, especially

those dependent on patency of ductus arteriosus, may go undiagnosed in

these settings.

Most studies reported from India are on prevalence at

a given point of time, and not on prevalence at birth. Many reported

studies are based on data from pediatric patients reporting to hospitals

leading to a possible sampling bias [9-14]. The profile of patients with

CHD that present to healthcare facilities in LMIC is largely determined

by the natural history of individual conditions. A high attrition of

patients with serious CHD results in low frequency of these lesions

encountered in hospital settings, and may contribute to the prevailing

perceptions on their rarity.

The true incidence or birth prevalence has been

reported only in few studies from India, which also include only babies

born in the hospital (Table I) [15-18]. In two of these

studies, echocardiography was performed for all newborns. The birth

prevalence of CHD in these studies was higher in comparison to data

available from other countries. Several other studies have reported the

prevalence of CHD during childhood, and, it varies from 1.3 to 9.2/1000

population (Table II) [19-27]. The wide variation is

partly explained by population studied and the diagnostic method used

for evaluation.

TABLE I Birth Prevalence of Congenital Heart Disease in India

|

Author [Ref.] |

No. screened |

Screening method |

No. with CHD |

Prevalence/ 1000 live births |

|

Khalil, et al. [15] |

10964 |

Clinical examination only |

43 |

3.9 |

|

Vaidyanathan, et al. [16] |

5487 |

Clinical, Pulse oximetry, |

Minor*: |

Minor CHD*:74.4 at

|

|

|

Echocardiography in all cases |

408 at birth 119 at

|

birth 21.7 at 6 weeks |

|

|

|

6 weeksMajor**:17 |

Major CHD**:3.1 |

|

Sawant, et al. [17] |

2636 |

Clinical; echocardiography in |

35 |

13.3

|

|

|

suspected cases only |

|

|

|

Saxena, et al. [18] |

20307 |

Clinical, Pulse oximetry,

|

Significant#: 164 |

Significant#: 8.1 |

|

|

Echocardiography in all cases

|

Major##: 71

Major##: 4.5/1000 |

(95% CI 6.94; 9.40)

|

|

CHD: congenital heart disease; *Those which are likely to

normalize by 6 weeks and include; atrial septal defect >5mm,

patent ductus Arteriosus >2 mm with left ventricular volume

overload, ventricular septal defect with gradient of >30 mmHg,

aortic stenosis/pulmonic stenosis with gradients of <25 mmHg and

pulmonary artery branch stenosis with gradients of <20 mmHg;

**CHD that is likely to require early intervention; #atrial

septal defect >5 mm, patent ductus arteriosus >2 mm with left

ventricle volume overload, restrictive VSD, and valvular

aortic/pulmonary stenosis with gradients <25 mmHg (in addition

to Major CHD); ##any CHD that is likely to require intervention

within the first year, including newborns with critical CHD that

require intervention within the first 4 weeks of life. |

TABLE II Prevalence of Congenital Heart Disease in Children Beyond Neonatal Age

|

Author [Ref] |

Age group

|

Setting |

Place of study |

Total No. |

Screening

|

No. with |

Prevalence |

|

(y) |

|

|

|

method |

CHD |

per 1000 |

|

Gupta, et al. 1992 [19] |

6-16 |

Community |

Jammu |

10263 |

Clinical |

8 |

0.8 |

|

Vashishtha, et al. 1993 [20] |

5-15 |

School |

Agra |

8449 |

Clinical |

44 |

5.2 |

|

Thakur, et al. 1995 [21] |

5-16

|

School |

Shimla |

15080 |

Clinical |

30 |

2.25 |

|

Chadha, et al. 2001 [22] |

<15

|

Community |

Delhi |

11833 |

Clinical |

50 |

4.2 |

|

Misra, et al. 2009 [23] |

4-18

|

School |

Eastern Uttar Pradesh |

118212 |

Clinical |

42 |

1.3

|

|

|

|

|

|

Echo for

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

suspected

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

cases only |

|

|

|

Kumari, et al. 2013 [24] |

5-16 |

School |

Dist. Prakasam,

|

4213 |

Clinical and |

39 |

9.2

|

|

|

|

Andhra Pradesh |

|

Echo in all |

|

|

|

Saxena, et al. 2013 [25] |

5-15 |

School |

Ballabgarh, Haryana |

14716 |

Clinical

|

3577 |

2.37 5.23

|

|

|

|

|

|

Clinical and

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

echo |

|

|

|

Bhardwaj, et al. 2016 [26] |

All age

|

Community |

Himachal Pradesh |

1882 |

Clinical |

12 |

6.312.95 |

|

groups |

|

|

(<18 y: |

Echo for

|

|

(in <18 y) |

|

19.5 y

|

|

|

660) |

suspected

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

cases only |

|

|

|

Nisale, et al. 2016 [27] |

1st to |

School |

Latur, Maharashtra |

3,53,761 |

Clinical |

143 |

0.4

|

|

10th class |

|

|

|

Echo for

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

suspected

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

cases only |

|

|

Current Status of Care in India

The issue of pediatric cardiac care in India has been

discussed earlier [28,29]. Gross disparity exists between high-income

countries and LMIC as far as care of children with CHD is concerned.

Whereas one cardiac center caters to a population of 120,000 in North

America, 16 million population is served by one center in Asia [30].

Similarly, the number of cardiac surgeons is also much more in North

America and Europe (one cardiac surgeon per 3.5 million population) as

compared to Asia (one cardiac surgeon per 25 million population) [3]. Of

the 240,000 children born with CHD each year in India, about one fifth

would need early intervention to survive the first year of life. A large

pool of older infants and children who may have survived despite no

intervention add to the burden of CHD.

Status of Care for Serious CHD

A number of cardiac care centers have come up in

India over the last decade. The total number approximates to 63; ten of

these can be considered high volume centers (more than 500 cardiac

surgeries per year). As per data provided by all large and medium volume

centers and a majority of small volume centers, a total of approximately

27,000 patients with CHD underwent cardiac surgery over a one-year

period (2016-2017). Of this, about 9,700 patients were infants (<1

year), and about 1700 were neonates (<1 month). Considering the birth

prevalence of serious CHD (requiring intervention in first year of life)

as 1.6/1000 live births, about 43,000 babies are born in India every

year with serious CHD, of which only about one-fourth seem to be

receiving optimal cardiac care. This proportion, though still very low,

is much better when compared with similar projections from India a

decade ago [5,31]. These data suggest that pediatric cardiac care is

gradually improving in India; although, we still have a long way to go.

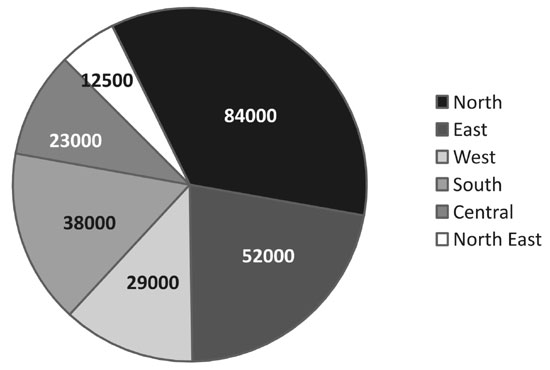

Regional Variations

There is marked regional variations in the population

and crude birth rates in various parts of India. The total number of

births are much higher in Northern and Eastern parts of India (Delhi,

Jammu and Kashmir, Punjab, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Rajasthan, Uttar

Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Bihar, Jharkhand, Orissa and West Bengal) as

compared to rest of four regions (Southern, Western, Central and

North-East). Consequently, the total number of babies born with CHD are

likely to be much more in regions with high birth rates (Fig.

1).

|

|

Fig. 1 Regional distribution of

infants born with CHD in India every year. (See color figure at

website)

|

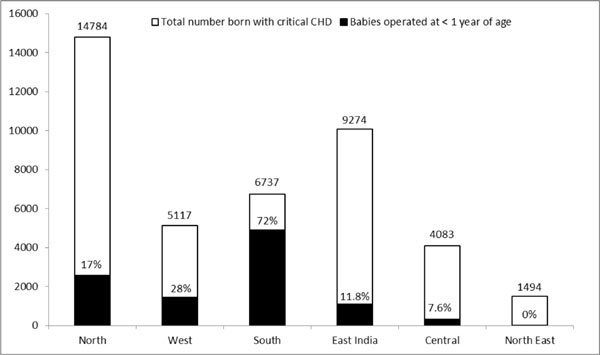

Based on the information provided by 47 centers in

India, there is a clear paradox as many centers are located in regions

with lower burden of CHD. When considering the critical CHD (requiring

intervention in first year of life), the Southern and Western states of

India have fared much better than other regions (Fig. 2).

On the contrary, states such as Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand and

Madhya Pradesh, which presumably have much higher CHD burden as compared

to the rest of states, have fared much worse. The data suggest that

children born with serious CHD in Southern India have a 70% chance of

receiving good cardiac care even if we consider that some of the

children operated in these centers are from other parts of India. In

contrast, babies born in Eastern and Central parts of India have a much

lower chance of receiving an intervention. This status may soon change

as the pediatric cardiac care centers start within the campuses of newly

opened government institutes (All India Institute of Medical Sciences).

These institutes are already operational in various states, including

those in eastern, central and northern parts of India. Currently, the

number of congenital heart surgeries is less in these institutes,

especially for neonates and infants.

|

|

Fig. 2 Regional distribution of

infants with critical heart disease accessing surgery as

compared to total number born with critical heart disease.

|

Obstacles to Pediatric Cardiac Care in India

Lack of awareness and delay in diagnosis: A

substantial proportion of births in India occur at home, and the infant

is likely to die before the critical, ductus-dependent CHD is diagnosed.

Fortunately, the rate of hospital deliveries have significantly

increased due to several incentivized schemes by the Government of

India. Ductus-dependent CHD may still escape detection as babies are

often discharged earlier. Pre-discharge screening of newborns by pulse

oximetry, which may pick up these CHDs, is often not practiced,

especially in rural and semi-urban centers. Frontline health workers and

primary caregivers are not sensitized to the problem of CHD and a number

of them believe that a child with CHD is doomed and will never be able

to lead a fruitful life, even if intervened. Delay in referral results

in poor outcomes as complications and co-morbidities (such as under-

nutrition) may have already set in.

Maldistribution of resources: The resources for

treatment of CHD are not only inadequate but also seriously

mal-distributed. As mentioned earlier, the geographical distribution of

these centers is very uneven. Poverty, which is the greatest barrier to

successful treatment of CHD is more common in states with little or no

cardiac care facilities. Transport of newborns and infants with CHD is

another neglected issue in India. There is practically no organized

system for safe transport of newborns and infants with CHD. The risks of

developing hypothermia and hypoglycemia during long, unsupervised

transport further adds to the already serious condition of the infants

with CHD [32]. Limited resources and inefficient governance further

compromise a fair distribution.

Financial constraints: Medical insurance is

practically nonexistent in India, especially for birth defects. In most

instances, families are expected to pay for the treatment out of their

pocket, which they can barely afford. In a study from Kerala [33],

surgery for CHD resulted in significant financial burden for majority of

families. Approximately half of the families borrowed money during the

follow-up period after surgery [33]. Many families lose their wages as

they are away from work during care of these children. Though several

state government level programs, microfinance schemes, charitable and

philanthropic organizations exist for the benefit of economically weaker

sections of the society, awareness amongst community about such programs

is very low. The number of public hospitals which provide care at a low

cost are very few. Most cardiac centers, especially those set-up more

recently, are in the private sector and may not be affordable for the

majority. Public hospitals are faced with a very large number of

patients and have waiting lists ranging from months to years. Children

undergoing surgery are often in advanced stages of disease with

associated malnutrition [34]. The results of intervention in such

settings are expected to be less than ideal.

According to data collected from 47 centers in India,

about 35% of cardiac surgeries are funded by families themselves.

Government schemes, mostly at state level, cover about 40% of all

surgeries for CHD patients. Many hospitals partner with charitable

non-government organizations and multinational companies to assist

economically weaker families. About 20% of cardiac surgeries are funded

by such organizations. Other less common (<5%) funding sources include

parents’ employer and donations. Some of the charitable cardiac centers

are providing completely free treatments; however, such centers

generally have long waiting lists.

Health seeking behavior of the community:

Often the parents seek medical care only when child develops significant

symptoms. This may not be only due to financial constraints. Local

religious and socio-cultural practices in India affect the level of care

received by children with CHD. Illiteracy may be partly contributing to

such behavior. Gender bias, as prevalent in some societies, may put

girls at a disadvantage compared to boys. In a study from a referral

tertiary care center, girls were less likely to undergo cardiac surgery

for CHD than boys [35].

Lack of follow-up care: Most children with CHD,

including those who have undergone an intervention, require long-term

care for a good outcome. Unfortunately, a large number of children in

India, especially those from middle or lower socioeconomic strata, are

lost to follow-up. The onus of follow-up is totally on the family of the

affected child as our health system is not proactive despite having a

network of primary health care units.

Other factors: Investment on healthcare is one of

the lowest in India when compared with several other countries,

including many LMIC. There is no national policy for CHD. Rapid

population growth, competing priorities, inefficient and inadequately

equipped infrastructure, and a deficit of trained staff at all levels of

healthcare are some of the other major roadblocks to cardiac care of

children with CHD.

Strategies for Improvement of Cardiac Care

To make meaningful reductions in mortality and

morbidity from CHD, it is imperative to focus on comprehensive newborn

and infant cardiac care. However, improvements in maternal and child

health services must occur simultaneously. Health is a state subject and

the various states of India differ vastly in their economy, literacy

levels, population, languages, cultural beliefs and human development

indices. This regional diversity makes the task more difficult as ‘one

size fits all’ approach is not tenable [36].

Increasing awareness: Community needs to be

sensitized to the problem of congenital defects, through electronic and

print media. Targeting pediatricians and educating them not just about

diagnosing CHD in a newborn, but also about the advancements that have

occurred in the care of children with CHD should also be helpful.

Preventive measures and screening: So far, little

emphasis has been placed on preventive measures for CHD. This needs to

be stressed as the investment required is much smaller. Mass

immunization against Rubella should be the starting point at the

national level. Although one can have a specific preventive program for

children with CHD, a more comprehensive program which caters to the

well-being of children in general, and incorporates a number of other

common disorders is more likely to be sustainable. A flagship scheme of

Government of India (Rashtriya Bal Swasthya Karyakram, RBSK) has been

launched in February 2013 with a mandate to screen all children, aged

0-18 years for early detection and management of birth defects and other

diseases. Under this initiative, comprehensive health care is expected

to be provided for all diagnosed cases of birth defects. Periodic

education programs to sensitize the practicing physicians and

pediatricians are necessary. The frontline health workers as well

community in general should be made aware of the availability of

advanced care in India for children with CHD. Screening newborns with

pulse oximetry to diagnose critical CHD should become a part of newborn

care [37].

Geographic distribution of centers of excellence:

Establishing more centers for cardiac care would be ideal, but this is a

very challenging task. One not only needs sophisticated technology and

infrastructure, but also a motivated team of health professionals.

Pediatric cardiac care is a team effort involving cardiologists,

surgeons, anaesthesiologists and intensive care specialists. There

should be at least one center in each state unit, may be more in

populous states, so that families do not have to travel long distances

to new cities with different local environments and languages. Ideally,

these centers should be supported by the government, either directly or

through welfare schemes, so that families belonging to middle and lower

strata on socioeconomic scale can also reap the benefits. This would

also maintain a high volume of cases, leading to professional

satisfaction and motivation of the employed staff.

Optimal utilization of resources: The model of

piggybacking pediatric cardiac program on a successful ongoing adult

cardiac program is useful for optimizing resource utilization, and has

been successfully used in several hospitals. The cardiac catheterization

laboratory, operating rooms, staff and other services are shared for

both pediatric and adult patients. In such ‘adult-program first’ models,

the pediatric cardiac program is gradually expanded. However, this model

is not without problems as adult care may get preference over pediatric

care as adult program are much less resource-intense. Collection of

outcome data to assess the quality of program is very important for

self-sustainability.

In-country training of staff: Currently India has

approximately 130 pediatric cardiologists and 110 pediatric cardiac

surgeons. These numbers are grossly inadequate, but are much better than

what it was a decade ago. Given a choice, very few specialists choose

pediatric cardiology and cardiac surgery as these specialities are much

more demanding, less glamorous and provide lower monetary return.

Hand-holding of new recruits by senior staff/expatriates on short-term

deputation from established cardiac centers, is likely to improve skills

and morale of junior surgeons. With ever increasing numbers of centers,

in-country structured training programs for pediatric cardiac care

specialists are necessary as has been successfully done in some

countries [38]. In the last five years or so, some good quality training

programs have started in India, including a three year courses in

pediatric cardiology. Incorporating research into a training program is

also very important, and helps in its sustainability.

Indigenization and innovation: For cardiac

surgery and interventions to be affordable, cost-containment is

necessary. Currently, majority of equipment and disposable items

required for cardiac surgery are being imported. Encouraging home grown

technology will reduce the cost of equipment considerably. Few LMIC,

such as Brazil and Mexico, are manufacturing products locally, reducing

the costs significantly. However, high standards have to be prescribed

for local manufacturers and a strict quality control is necessary.

Prioritization of care: A contentious issue is

prioritizing CHD care for those cases which are ‘one time fixes’ with

good long-term outcome over those with complex CHD requiring multistage,

often palliative surgeries with suboptimal long-term survival. This

issue gains importance because of the enormous burden of CHD in India

and availability of limited facilities for their management. The denial

of cardiac surgery to children with complex CHD and single ventricle

physiology (e.g., heterotaxy syndromes) and to those associated

with significant extra-cardiac malformations is for efficient resource

utilization in a resource-constrained setting. Such decisions can be

challenged and are best taken in consultation with parents.

Providing financial support for treatment: A

number of financial models are supporting healthcare in India. Many of

them cater to children and cover for CHDs. Some of the private hospitals

support patients utilizing funding from corporate social responsibility

programs. Payment is sometimes linked to the patient’s capacity to pay,

helping to subsidize services for poorer patients. Charitable hospitals

often depend on donations. Insurance is another way to provide high

quality care. One of the successful schemes adopted by Karnataka, called

Yeshashwini, is a microfinance scheme where each member of a cooperative

group pays a nominal amount to create a corpus which is used to fund

surgeries [39]. Several other states have similar schemes under

different names. A number of initiatives by the central government are

directed at health of children. Provision is also provided for free

treatment of children from families which are below poverty line. In

addition, poor patients can get financial help from Prime Minister’s

Relief Fund and Chief Minister’s Relief Fund. The policy makers and

others in the government are taking note of pediatric health, and in

future, we may see more schemes for the benefit of children with CHD.

However, we must have the infrastructure to take care of this increasing

demand.

Recently government of India has launched a

National Health Protection Scheme, which is a flagship program

under Ayushman Bharat [40]. This scheme is expected to cover over 10

crore poor and vulnerable families (approximately 50 crore people).

Under this scheme, a coverage up to Rs. 500,000 per family per year will

be provided, for secondary and tertiary care hospitalization. Whether

this scheme would significantly impact the cardiac care of children with

CHD is to be seen, considering the mismatch between the high load of

cases and number of cardiac care centers in India.

Conclusion

The care available for children with CHD is vastly

different in MIC, including India, from that in high-income countries. A

large proportion of children with CHD go undiagnosed and untreated in

India due to the large numbers and limited resources. A significant

amount of progress has been made in India for the management of children

with CHD over the last three decades, but it still remains grossly

inadequate. Interactions with pediatricians and other front line health

staff are necessary to improve the overall outlook for children with

CHD. Advocacy with health policy makers is very important so that more

resources are allocated to care of children with CHD – at primary,

secondary and tertiary levels. Potential solutions to improve access to

cardiac care must consider the local social, economic and political

systems for each region. A locally relevant research must be a part of

this endeavor.

Acknowledgements: The author thanks all the

participating centers and the specialists who provided their centers’

data. A complete list is given below:

Prem Alva (AJ Hospital and Research

Centre, Mangalore), Sachin Talwar (All India Institute of Medical

Sciences, New Delhi), R Krishna Kumar (Amrita Institute of

Medical Sciences, Kochi), Muthukumaran C Sivaprakasam, Neville

A G Solomon (Apollo Children’s Hospitals, Chennai), Vikas Kohli

(Apollo Hospital, New Delhi), Nidhi Rawal, Viresh Mahajan, Aseem

R Srivastava, Pradipta K Acharya (Artemis Hospital, Sector 51,

Gurugram), Renu P Kurup (Aster MIMS Calicut), K Nageswara Rao

(Care Hospital, Hyderabad), KS Iyer (Fortis Escorts Heart

Institute and Research Centre, New Delhi), Swati Garekar (Fortis

Hospital, Mulund, Mumbai), Raghavan Subramanyan (Frontier

Lifeline Hospital, Chennai), Sumodh Kurien (G B Pant

Hospital, New Delhi), Sanjay Gandhi, Ramesh Patel (Geetanjali

Medical College & Hospital (Geetanjali Cardiac Center), Udaipur), M

Kalyanasundaram (GKNM Hospital Coimbatore), Jayakumar TK

(Govt. Medical College Kottayam), Shaad Abqari (Jawaharlal Nehru

Medical College Hospital, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh), Smita

Mishra (Jaypee Hospital, Sector-128, Noida), R Prem Sekar,

Karthik Surya (Kauvery Hospital Chennai), Snehal Kulkarni (Kokilaben

Ambani Hospital, Mumbai), Sudeep Verma, Gouthami V (Krishna

Institute of Medical Sciences (KIMS), Secunderabad), S Devaprasath

(Kovai Children Heart Center & Sri Ramakrishna Hospitals, Coimbatore),

Edwin Francis (Lisie Heart Institute, Kochi), K Sivakumar

(Madras Medical Mission, Chennai), Neeraj Awasthy (Max

Superspeciality Hospital, New Delhi), Amit Misri (Medanta

Medicity, Gurugram, Haryana), Anil Singhi (Medica

Hospital, Kolkata), R Saileela, Robert Coelho (MIOT centre for

Children’s Cardiac Care, Chennai), Karan Dave (Narayana Institute

of Cardiac Sciences Bangalore), Emmanuel Rupert, Debasis Das (Narayana

Superspeciality Hospital, Howrah), Prashant Mahawar (Narayana

Multi-specialty Hospital, Jaipur), Biswajit Bandyopadhyay (NH

Rabindranath Tagore International Institute of Cardiac Sciences,

Kolkata), Manoj Kumar Rohit (PGIMER Advanced Cardiac Centre,

Chandigarh), Dinesh Kumar,Vijay Gupta, Dheeraj Deo Bhatt (PGIMER

and Dr RML Hospital, New Delhi), Siddharth Gadage (Ruby Hall

Clinic, Pune), Sudeep Kumar (Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate Institute

of Medical Sciences, Lucknow), Shivaprakash K (Sir HN Reliance

Foundation Hospital, Girgaum), Raja Joshi, Neeraj Aggarwal (Sir

Ganga Ram Hospital, New Delhi), K M Krishnamoorthy, Deepa S Kumar,

Arun Gopalakrishnan (Sree Chitra Tirunal Institute for Medical

Sciences and Technology, Trivandrum), Ashish Katewa, Balswaroop Sahu

(Sri Sathya Sai Sanjeevani Hospital, Raipur), Jayranganath M, Usha MK

(Sri Jayadeva Institute of cardiovascular Sciences and

Research, Bangalore), Anupama Rao, Krishna Manohar (Sri Sathya

Sai Institute of Higher Medical Sciences, Whitefield, Bangalore),

Saji Philip (St. Gregorios Cardio Vascular Centre, Parumala),

Nitin Rao, Ramkinkar Shastri (STAR Hospitals, Hyderabad), Srirup

Chatterjee (The Mission Hospital, Durgapur, West Bengal), Nilesh

K Oswal (UN Mehta Institute of Cardiology and Research Centre, Ahmedabad),

BRJ Kannan (Vadamalayan Hospitals, Madurai), Sumitra

Venkatesh, S S Prabhu, Biswa R Panda (Wadia Children’s Cardiac

Centre, Mumbai).

|

Key Messages

• Over 200,000 children are estimated to be

born with congenital heart disease in India every year.

• About one-fifth of these suffer from

critical heart disease requiring early intervention.

• The currently available care for these

children is grossly inadequate.

• There are over 60 centers that cater to

children with congenital heart disease; majority are in southern

states of India.

• Most of babies born with congenital heart

disease in most populous states of India, such as Uttar Pradesh

and Bihar, do not receive the care they deserve.

• Improving care of children with congenital

heart disease is an uphill task, but needs to be addressed.

|

References

1. Dolk H, Loane M, EUROCAT Steering Committee.

Congenital Heart Defect in Europe: 2000-2005. Newtownabbey, Northern

Ireland: University of Ulster; March 2009. Available from:

http://eurocat.bio-medical.co.uk/content/Special-Report.pdf.

Accessed May 18, 2017.

2. Bernier PL, Stefanescu A, Samoukovic G,

Tchervenkov CI. The challenge of congenital heart disease worldwide:

epidemiologic and demographic facts. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg

Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 2010;13:26-34.

3. Hoffman JIE. The global burden of congenital heart

disease. Cardiovascular J Africa. 2013;24:141-5.

4. Hoffman JIE. Incidence of congenital heart

disease: I. Postnatal incidence. Pediatr Cardiol. 1995;16:103-13.

5. Saxena A. Congenital heart disease in India: A

status report. Indian J Pediatr. 2005;72:595-8.

6. Hoffman JI, Kaplan S. The incidence of congenital

heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1890-900.

7. van der Linde D, Konings EM, Slager MA, Witsenburg

M, illem Helbing A, Johanna JM, et al. Birth prevalence of

congenital heart disease worldwide. A systematic review and

meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:2241-7.

8. Kothari SS, Gupta SK. Prevalence of congenital

heart disease. Prevalence of congenital heart disease. Indian J Pediatr.

2013;80:337-9.

9. Kapoor R, Gupta S. Prevalence of congenital heart

disease, Kanpur, India. Indian Pediatr. 2008;45:309-11.

10. Bhat NK, Dhar M, Kumar R, Patel A, Rawat A, Kalra

BP. Prevalence and pattern of congenital heart disease in Uttarakhand,

India. Indian J Pediatr. 2013;80:281-5.

11. Wanni KA, Shahzad N, Ashraf M, Ahmed K, Jan M,

Rasool S. Prevalence and spectrum of congenital heart diseases in

children. Heart India. 2014;2:76-9.

12. Kiran B, Chintan S, Reddy C, Savitha S, Medhar

SS, Keerthana TN. Study of prevalence of congenital heart diseases in

children in a rural tertiary care hospital. J Pediatr Res.

2016;3:887-90.

13. Abqari S, Gupta A, Shahab T, Rabbani MU, Ali SM,

Firdaus U. Profile and risk factors for congenital heart defects: A

study in a tertiary care hospital. Ann Pediatr Cardiol. 2016;9:216-21.

14. Mahapatra A, Sarangi R, Mahapatra PP. Spectrum of

congenital heart disease in a tertiary care centre of Eastern India. Int

J Contemp Pediatr. 2017;4:314-6.

15. Khalil A, Aggarwal R, Thirupuram S, Arora R.

Incidence of congenital heart disease among hospital live births in

India. Indian Pediatr. 1994;31:519-27.

16. Vaidyanathan B, Sathish G, Mohanan ST, Sundaram

KR, Warrier KK, Kumar RK. Clinical screening for congenital heart

disease at birth: A prospective study in a community hospital in Kerala.

Indian Pediatr. 2011;48:25-30.

17. Sawant SP, Amin AS, Bhat M. Prevalence, pattern

and outcome of congenital heart disease in Bhabha atomic research centre

hospital. Indian J Pediatr. 2013;80:286-91.

18. Saxena A, Mehta A, Sharma M, Salhan S, Kalaivani

M, Ramakrishnan S, et al. Birth prevalence of congenital heart

disease: A cross sectional observational study from North India. Ann

Pediatr Cardiol. 2016;9:205-9.

19. Gupta I, Gupta ML, Parihar A, Gupta CD.

Epidemiology of rheumatic and congenital heart disease in rural

children. J Indian Med Assoc. 1992;90:57-9.

20. Vashishtha VM, Kalra A, Kalra K, Jain VK.

Prevalence of congenital heart disease in school children. Indian

Pediatr. 1993;30:1337-40.

21. Thakur JS, Negi PC, Ahluwalia SK, Sharma R,

Bhardwaj R. Congenital heart disease among school children in Shimla

hills. Indian Heart J. 1995;47:232-5.

22. Chadha SL, Singh N, Shukla DK. Epidemiological

study of congenital heart disease. Indian J Pediatr. 2001;68:507-10.

23. Misra M, Mittal M, Verma AM, Rai R, Chandra

G, Singh DP, et al. Prevalence and pattern of congenital heart

disease in school children of eastern Uttar Pradesh. Indian Heart J.

2009;61:58-60.

24. Rama Kumari N, Bhaskara Raju I, Patnaik AN, Barik

R, Singh A, Pushpanjali A, et al. Prevalence of rheumatic and

congenital heart disease in school children of Andhra Pradesh, South

India. J Cardiovasc Dis Res. 2013;4:11-4.

25. Saxena A. Echocardiographic prevalence of

congenital cardiac malformations among 14,716 asymptomatic school

children in India. Presented at EuroEcho Imaging 2013.

26. Bhardwaj R, Kandoria A, Marwah R, Vaidya P, Singh

B, Dhiman P, et al. Prevalence of congenital heart disease in

rural population of Himachal - A population -based study. Indian Heart

J. 2016;68:48-51.

27. Nisale SH, Maske GM. A study of prevalence and

pattern of congenital heart disease and rheumatic heart disease among

school children. Int J Adv Med. 2016;3:947-51.

28. Kothari SS. Pediatric cardiac care for the

economically disadvantaged in India: Problems and prospects. Ann Ped

Cardiol. 2009;2:95-8.

29. Kumar RK. The nuts and bolts of pediatric cardiac

care for the economically challenged. Ann Ped Cardiol. 2009; 2:99-101.

30. Pezzella T. Worldwide maldistribution of access

to cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;123:1016-17.

31. Kumar RK, Shrivastava S. Pediatric heart care in

India. Heart. 2008;94:984-90.

32. Kumar RK. Congenital heart disease profile: Four

perspectives. Ann Pediatr Cardiol. 2016;9:203-4.

33. Raj M, Paul M, Sudhakar A, Varghese AA, Haridas

AC, Kabali C, et al. Micro-economic impact of congenital heart

surgery: Results of a prospective study from a limited-resource setting.

PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131348.

34. Liu J. Challenges and progress of the pediatric

cardiac surgery in Shanghai Children’s Medical Center: A 25-year solid

collaboration with Project HOPE. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr

Card Surg Annu. 2009;12:12-8.

35. Ramakrishnan S, Khera R, Jain S, Saxena A,

Kailash S, Karthikeyan G, et al. Gender differences in the

utilisation of surgery for congenital heart disease in India. Heart.

2011; 97:1920-5.

36. Saxena A. Pediatric cardiac care in India:

Current status and the way forward. Future Cardiol. 2018;14:1-4.

37. Saxena A, Mehta A, Ramakrishnan S, Sharma M,

Salhan S, Kalaivani M, et al. Pulse oximetry as a screening tool

for detecting major congenital heart defects in Indian newborns. Arch

Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2015;100:F416-21.

38. Pezzella AT. Cardiothoracic surgery residency

program in Shanghai, China. Ann Afr Chir Thor Cardiovasc. 2009;4:81-99.

39. Maheshwari S, Kiran VS. Cardiac care for the

economically challenged: What are the options? Ann Pediatr Cardiol.

2009;2:91-4.

40. Lahariya C. ‘Ayushman Bharat’ program and

universal health coverage in India. Indian Pediatr. 2018;55:495-506.

|

|

|

|

|