|

|

|

Indian Pediatr

2017;54:1012-1016 |

|

Prevalence of

Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Normal-weight and Overweight

Preadolescent Children in Haryana, India

|

|

Manoja Kumar Das, #Vidyut

Bhatia, #Anupam

Sibal, *Abha

Gupta, #Sarath

Gopalan,

‡Raman Sardana, $Reeti

Sahni, #Ankur Roy

and Narendra K Arora

From The INCLEN Trust International, F1/5, Okhla

Industrial Area, Phase I, New Delhi; and Departments of #Pediatric

Gastroenterology and Hepatology, *Biochemistry, ‡Microbiology

and $Radiodiagnosis, Indraprastha Apollo Hospitals, Sarita

Vihar, New Delhi; India.

Correspondence to : Dr Manoja Kumar Das, MD, Director

Projects, The INCLEN Trust International, F1/5, Okhla Industrial Area,

Phase I, New Delhi 110020, India.

Email: [email protected]

Received: December 10, 2016;

Initial review completed: February 20, 2017;

Accepted: September 29, 2017.

|

Objective: To document the prevalence of

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and metabolic parameters among

normal-weight and overweight schoolchildren.

Study design: Cross-sectional study.

Setting: Thirteen private schools in urban

Faridabad, Haryana.

Participants: 961 school children aged

5-10 years.

Methods: Ultrasound testing was done, and 215

with fatty liver on ultrasound underwent further clinical, biochemical

and virological testing.

Outcome measures: Prevalence of fatty liver on

ultrasound, and NAFLD and its association with biochemical abnormalities

and demographic risk factors.

Results: On ultrasound, 215 (22.4%) children had

fatty liver; 18.9% in normal-weight and 45.6% in overweight category.

Presence and severity of fatty liver disease increased with body mass

index (BMI) and age. Among the children with NAFLD, elevated SGOT and

SGPT was observed in 21.5% and 10.4% children, respectively. Liver

enzyme derangement was significantly higher in overweight children (27%

vs 19.4% in normal-weight) and severity of fatty liver (28% vs

20% in mild fatty liver cases). Eleven (8.1%) children with NAFLD had

metabolic syndrome. Higher BMI (OR 35.9), severe fatty liver disease (OR

1.7) and female sex (OR 1.9) had strong association with metabolic

syndrome.

Conclusions: 22.4% of normal-weight and

overweight children aged 5-10 years had fatty liver. A high proportion

(18.9%) of normal-weight children with fatty liver on ultrasound

indicates the silent burden in the population.

Key words: Fatty Liver Disease, Metabolic Syndrome, NAFLD.

|

|

N

on-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is

defined as the accumulation of fat in the hepatocytes (>5-10% by weight)

in the absence of any known liver pathology or excessive alcohol

consumption [1]. NAFLD is the commonest cause of chronic liver disease

in young people in the developed countries [2,3]. Paralleling

overweight/obesity epidemiology, NAFLD report is also rising. Prevalence

of fatty liver in the general adult population of India is in the range

of 5% to 28%, with higher prevalence among the overweight and diabetics

[4-6]. Prevalence of childhood NAFLD globally is in the range of 9 to

37% [7,8]. Further, the prevalence of NAFLD in normal-weight children

and overweight/obese children is reported to range about 3-10% and

8-80%, respectively [9]. Presence of NAFLD varies according to the

methodology and diagnostic criteria used [10]. Overweight/Obesity,

dyslipidemia, insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome, ethnicity,

gender and familial clustering are documented as risk factors for NAFLD

in adults and children [9,11,12].

The increasing burden of obesity and non-communicable

diseases across all ages warrants documentation of NAFLD burden. There

is limited information about NAFLD among Indian preadolescent children.

We undertook this study to document the prevalence of NAFLD among urban

normal-weight and overweight school children in a northern Indian state,

and its association with insulin resistance and other components of

metabolic syndrome.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study that included urban

school children aged ³5

years and £10

years from Faridabad district, Haryana. We adopted intelligent two stage

sampling: (1) selection of schools and (2) selection of suitable

children from the schools. Thirteen private schools were identified

randomly from the list of schools with District Education Office. After

obtaining informed written consent from parents, all the children in

eligible age group were screened for weight, height and blood pressure.

Weight and height were measured using electronic weighing scale

(precision 100 grams) and Leicester Stadiometer (precision 0.1 cm), and

Body mass index (BMI) calculated. Blood pressure was measured using

electronic sphygmomanometer after resting for 10 minutes. Three measures

for child each were obtained and mean of the measures was used.

Date of birth was verified from the school register. Using the

International Obesity Task Force (IOTF) reference for BMI, the children

were categorized into underweight, normal-weight and overweight (BMI

corresponding to <18.5, ³18.5-<25

and ³25 at 18

years of age, respectively) [13,14]. Children falling in the underweight

category were excluded to avoid influence of fatty liver associated with

undernutrition.

Ultrasonography (USG) abdomen was done at

Indraprastha Apollo hospital by a radiologist using Sonosite (Fujifilm

Sonosite Inc.) machine with 3.5 MHz convex-type transducer among

randomly selected children from the above. All the ultrasound images

were saved and reviewed by senior radiologist, and repeated in 10% of

the children. Ultrasound findings were categorized into absent, mild,

moderate and severe fatty liver disease, as per Needleman criteria [15].

Parents of the children with fatty liver on

ultrasound were approached for consent for second part of study for

detailed clinical examination and anthropometry, blood biochemistry, and

virological evaluation. Waist circumference and hip circumference were

measured using non-stretchable tape (Seca 201). Waist circumference

above 90 th percentile for

the age and gender was considered as abnormal [16]. Children with

hypertension were identified using the BP reference given by Manu Raj,

et al. [17]. Fasting venous blood sample (6 mL) was drawn for all

enrolled children, serum was separated within 2 hours and analyzed

within 24 hours. Blood glucose, liver function tests and lipid profile

were measured. Serum ceruloplasmin was analyzed by the

immunoturbidimetry method. Hepatitis B antigen (HBsAg) and

Anti-hepatitis C (HCV) assays were done by ELISA using kits (VIDAS

Biomeriex, France and Orthodiagnostics, USA, respectively). Internal

and external quality control protocols for continuous quality assurance

was adopted in the laboratory. Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and

aspartate aminotransferase (AST) >40 IU/L were considered as raised.

Metabolic syndrome was defined by abnormality of any three of the

parameters: fasting glucose >100 mg/dL, triglyceride >110 mg/dL,

high-density lipoprotein (HDL) <38 mg/dL, hypertension (blood pressure

>95th percentile for systolic blood pressure/diastolic blood

pressure/mean arterial blood pressure) and obesity (>95th percentile

BMI) [18].

Assuming prevalence of NAFLD in normal-weight and

overweight children to be in the range of 12% and 55% (relative

admissible error ±20%) at 95% confidence level, the sample size needed

was 704 and 80, respectively. Considering the estimated prevalence of

overweight in the range of 12-15%, a sample size of 960 children for

ultrasound was planned.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional

Ethics Committees of both Inclen Trust International and Indraprastha

Apollo Hospital. Data analysis was done by STATA using descriptive

statistics (means and standard deviations), Mann-Whitney Test, unpaired

t-test and chi-square test. A P value less than 0.05 was

considered significant.

Results

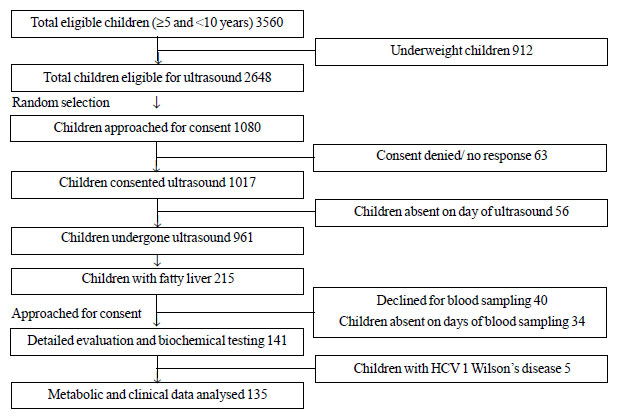

A total of 3560 children aged

³5 and <10 years

(2087 boys and 1473 girls) were screened. Out of the children screened,

2092 were normal-weight, 402 were overweight and 154 were obese. A total

of 961 children (528 boys) underwent ultrasound examination (Fig.

1), out of which 836 were in normal-weight category and 125 in

overweight category. There was comparable representation from age-bands

among the children who underwent ultrasound and those which did not.

|

|

Fig. 1 Study participation flow chart.

|

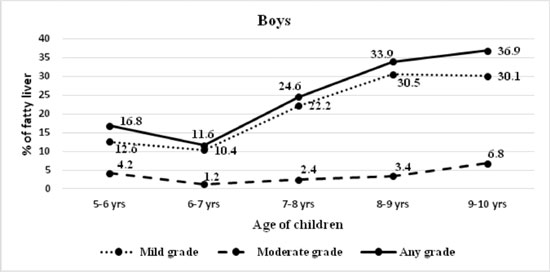

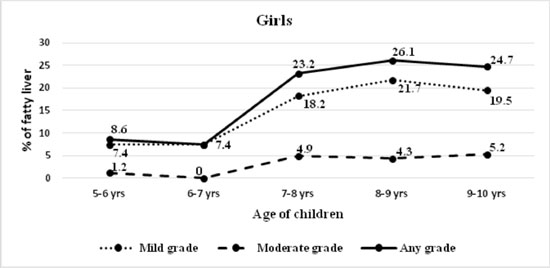

Out of these 215 (22.4%; boys 25.6% and girls 18.5%)

had fatty liver on ultrasound. Out of the 215 children with fatty liver,

110 had mild degree and 25 had moderate degree and none had severe

degree. The prevalence of fatty liver increased with age in both boys

and girls, from 13.1% in 5-6 years to 31% in 9-10 years age-group (Fig.

2). Boys had a higher risk of fatty liver (OR 1.5; 95% CI 1.3-1.8).

(a) |

(b) |

|

Fig. 2 Severity of fatty liver

diagnosed on ultrasound in (a) boys; and (b) girls.

|

Proportion of fatty liver among overweight children

was 45.6%, twice than the normal-weight children (18.9%); which was

similar in both boys (48.5% and 22.3%, respectively) and girls (42.4%

and 14.7%, respectively). Higher BMI was observed to be a risk factor

for fatty liver in both sexes [boys, OR 3.28 (95% CI 2.96-3.64); girls,

OR 4.26 (95% CI 3.96-4.52); all children OR 3.59 (95% CI 2.9- 4.5)].

Only few children had any symptoms and/or signs like pain abdomen

(6.4%), jaundice (2.8%) or vomiting (2.1%). Family history of

hypertension, diabetes and liver disease were present in 12.8%, 6.4% and

3.5% of children, respectively and there was no relationship with

severity of fatty liver.

Detailed biochemical evaluation could be done in 141

children. AST and ALT levels were raised in 29 (21.5%) and 14 (10.4%)

children, respectively. AST level was elevated in 19.4% of normal-weight

children and 27% of the overweight children. SGPT level was elevated in

35% of overweight children and 1% of the normal-weight children.

TABLE I Metabolic Parameters in Children with Fatty Liver

|

Parameters |

Fatty liver, n(%) |

|

Mild

(n=109) |

Moderate

(n=26) |

Total

(n=135) |

|

Obese |

29 (26.6) |

8 (30.8) |

37 (27.4) |

|

Hypertension |

10 (9.2) |

3 (11.5) |

13 (9.6) |

|

Hyperglycemia |

13 (11.9) |

3 (11.5) |

16 (11.8) |

|

Hypertriglyceridemia |

26 (23.8) |

6 (23) |

32 (23.7) |

|

Low HDL |

39 (35.8) |

13 (50) |

52 (38.5) |

|

*Metabolic syndrome |

8 (7.3) |

3 (11.5) |

11 (8.1) |

|

*Metabolic syndrome was defined as presence of any three of

the five parameters. |

Low HDL (38.5%) and hypertriglyceridemia (23.7%) were

the commonest metabolic derangements observed (Table I).

The 11 children with metabolic syndrome had hypertriglyceridemia (100%),

obesity (91%), and low HDL (82%) as prominent features. When compared

across the BMI categories; low HDL level was comparable among

normal-weight (37.8%) and overweight children (38.1%), but increased

among obese children (43.8%; P=0.04). The hypertriglyceridemia

proportion increased with BMI; 16.3% in normal-weight, 33.3% in

overweight (P=0.04) and 56.3% in obese (P=0.005)

categories. Similarly the prevalence of hypertension increased with BMI;

8.2% among normal-weight, 14.3% in overweight (P=0.03) and 12.5%

in obese (P=0.04) categories. Proportion of children with low HDL

level and hypertension was higher with higher severity of fatty liver (Table

I). Higher BMI (OR 35.9; 95% CI 28.5-41.2), severe fatty liver

disease (OR 1.7; 95% CI 1.32-1.96) and female sex (OR 1.9; 95% CI

1.4-2.24) had an association with metabolic syndrome.

Discussion

This study documented fatty liver on ultrasound in

22.4% of selected children (45.6% in overweight children, 18.9% in

normal-weight children). Presence of fatty liver increased with rise in

BMI, and derangement in liver enzymes increased with fatty liver

severity and BMI. Low HDL and hypertriglyceridemia were the commonest

metabolic derangements observed.

Exclusion of under-weight children, including only

private school students, and non-availability of liver biopsy findings

for confirmation of NAFLD are some of the limitations of the present

study.

Reports on NAFLD among Indian children are limited.

Among 4-18 years old Kashmiri school children, NAFLD was documented in

7.4% in all children (26% in obese children) [19]. In a hospital-based

study from Delhi, 3% of children aged 5-12 years had fatty liver [20].

NAFLD was documented on ultrasound in 33.9% normal-weight and 66.1% of

overweight adolescents aged 11-15 years in Mumbai [21]. We documented

higher proportion of NAFLD among normal-weight children, but the

proportion in over-weight/obese children was comparable. Among Iranian

children with NAFLD, raised liver enzymes were reported in 4.1% and 6.6%

of the normal-weight children and 16.9% and 14.9% of the obese children

(6-18 years), respectively [11]. Although higher proportion of liver

enzyme derangement was observed in our study, the trend across the BMI

category and severity of fatty liver was consistent. Proportion of

metabolic syndrome with NAFLD was comparable to reports among children

from China (32%), Japan (30%) and North America (26%) [22-24].

In conclusion, the present observation indicates high

prevalence of fatty liver in normal-weight and overweight children aged

5-10 years. This early onset of NAFLD in childhood points towards rising

prevalence coupled with increasing overweight/obesity, although the

carry-over effect of transition from underweight to normal-weight or

overweight cannot be ruled out. The current practice of NAFLD screening

based on high BMI is likely to miss a sizable number of normal-weight

children with NAFLD, who are also at risk for progression. Further

research is needed to address the biological basis and associations with

various risk factors and potential interventions to prevent and/or

reverse NAFLD. Additionally, lack of appropriate cut-offs for various

metabolic parameters in metabolic syndrome in Indian children makes

comparison and trend analysis challenging. With high burden of

undernutrition, the prevalence of fatty liver among children related to

overweight and metabolic syndrome may be different from the published

reports.

Contributors: All authors have contributed,

designed and approved the study.

Funding: Indian Council of Medical

Research (NCD/ADHOC/93/2010-11). Competing interest: None.

|

What is Already Known?

•

Prevalence of fatty liver and NAFLD is high in children with

higher BMI (overweight or obese).

What This Study Adds?

•

A high proportion of

normal-weight children also have NAFLD and metabolic

derangements.

|

References

1. Bellentani S, Marino M. Epidemiology and natural

history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Ann Hepatol.

2009;8:S4-S8.

2. Schwimmer JB, Deutsch R, Kahen T, Lavine JE,

Stanley C, Behling C. Prevalence of fatty liver in children and

adolescents. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1388-93.

3. Wieckowska A, Feldstein AE. Diagnosis of

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: invasive versus non-invasive. Semin

Liver Dis. 2008;28:386-95.

4. Amarapurkar D N, Hashimoto E, Lesmana LA, SoIlano

JD, Chen PJ, Goh KL, Asia-Pacific Working Party on NAFLD. How common is

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in the Asia-Pacific region and are

there local differences? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:788-93.

5. Duseja A. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in

India- a lot done, yet more required! Indian J Gastroenterol.

2010;29:217-25.

6. Bajaj S, Nigam P, Luthra A, Pandey RM, Kondal D,

Bhatt SP, et al. A case-control study on insulin resistance,

metabolic co-variates & prediction score in non-alcoholic fatty liver

disease. Indian J Med Res. 2009;129:285-92.

7. Jou J, Choi SS, Diehl AM. Mechanisms of disease

progression in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Semin Liver Dis.

2008;28:370-9.

8. Hesham AK. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in

children living in the obeseogenic society. World J Pediatr.

2009;5:245-54.

9. Widhalm K, Ghods E, Nonalcoholic fatty liver

diseases: a challenge for pediatricians. Int J Obes (Lond).

2010;34:1451-67.

10. Anderson EL, Howe LD, Jones HE, Higgins JPT,

Lawlor DA, Fraser A. The prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

PLoSONE. 2015;10:e0140908.

11. Kelishadi R, Cook SR, Adibi A, Faghihimani Z,

Ghatrehsamani S, Beihaghi A, et al. Association of the components

of the metabolic syndrome with non- alcoholic fatty liver disease among

normal-weight, overweight and obese children and adolescents. Diabetol

Metab Syndr. 2009;1:29.

12. Fu JF, Shi HB, Liu LR, Jiang P, Liang L, Wang CL.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: An early mediator predicting

metabolic syndrome in obese children? World J Gastroenterol.

2011;17:735-42.

13. Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH.

Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity

worldwide: international survey. BMJ. 2000;320:1240-3.

14. Cole TJ, Flegal KM, Nicholls D and Jackson AA.

Body mass index cut offs to define thinness in children and adolescents:

international survey. BMJ. 2007;335:194.

15. Needleman L, Kurtz AB, Rifkin MD, Cooper HS,

Pasto ME, Goldberg BB. Sonography of diffuse benign liver disease:

accuracy of pattern recognition and grading. Am J Roentgenol.

1986;146:1011-5.

16. McCarthy HD, Jarrett KV, Crawley HF. The

development of waist circumference percentile in British children aged

5.0-16.9 y. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2001;55:902-7.

17. Raj M, Sundaram KR, Paul M, Deepa AS, Kumar RK.

Obesity in Indian children: time trends and relationship with

hypertension. Natl Med J India. 2007;20:288-93

18. Ferreria AP, Oliveria CER, Franca NM. Metabolic

syndrome and risk factors for cardiovascular disease in obese children;

the relationship with insulin resistance (HOMA-IR). J Pediatr.

2007;83:21-6.

19. Irshad, Zargar SA, Khan BA, Ahmad B, Saif RU,

Kawoosa A, et al. Ultrasonographic prevalence of non–alcoholic

fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in Kashmir valley school children. Int J Sci

Res. 2013;2:299-301.

20. Chaturvedi K and Vohra P. Non-alcoholic fatty

liver disease in children. Indian Pediatr. 2012;49:757-8.

21. Pawar SV, Zanwar VG, Choksey AS, Mohite AR, Jain

SS, Surude RG, et al. Most overweight and obese Indian children

have nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Ann Hepatol. 2016;15:853-61.

22. Jun-Fen Fu, Hong-Bo Shi, Li-Rui Liu, Ping Jiang,

Li Liang, Chun-Lin Wang, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver

disease: An early mediator predicting metabolic syndrome in obese

children? World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:735-42.

23. Tominaga K, Fujimoto E, Suzuki K, Hayashi M,

Ichikawa M, Inaba Y. Prevalence of non alcoholic fatty liver disease in

children and relationship to metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance and

waist circumference. Environ Health Prev Med. 2009;14:142-9.

24. Patton HM, Yates K, Arida AU, Behling CA, Huang

TTK, Rosenthal P, et al. Association between metabolic syndrome

and liver histology among children with nonalcoholic fatty liver

disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2093-102.

|

|

|

|

|