|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2016;53: 1105-1106 |

|

Chemical Pleurodesis with Oxytetracycline in

Congenital Chylothorax

|

|

Alpana Utture, Vinayak Kodur and Jayashree Mondkar

From Department of Neonatology, Lokmanya Tilak

Municipal Medical College & General Hospital, Sion, Mumbai, India

Correspondence to: Dr Alpana Utture, Associate

Professor, Department of Neonatology,

LTMMC and LTMGH, Mumbai, India.

Email: [email protected]

Received: November 21. 2015;

Initial review: March 05, 2016;

Accepted: August 09, 2016.

|

Background: Congenital chylothorax is an accumulation of chyle in

the pleural space that may present in neonatal period with respiratory

distress. Case Characteristics: A 34-week preterm who presented

with massive congenital chylothorax complicated with hydrops fetalis.

Outcome: The neonate was treated successfully by pleurodesis with

Oxytetracycline. Message: Pleurodesis with oxytetracycline seems

to be effective in treatment of congenital chylothorax.

Keywords: Chyle, Ligation, Management, Neonate, Pleural

effusion.

|

|

C

hylothorax may be congenital, and occurs due to

lymphatic malformations like lymphangioma, lymphangiectasia and atresia

of the thoracic duct. Acquired chylothorax occurs due to trauma and

post-cardiac surgery. It is also known to be associated with conditions

that increase intrathoracic pressure, like superior vena cava thrombosis

[1]. As chyle is composed of fats, immune cells and proteins,

chylothorax is also associated with metabolic, nutritional and

immunological morbidities, apart from respiratory problems. When

chylothorax is associated with hydrops, it is a potentially

life-threatening condition. Initial treatment is conservative, and

includes keeping the baby nil-by-mouth (NBM), and administration of

total parenteral nutrition (TPN). Octreotide, a somatostatin analogue,

has shown promising results in the treatment of congenital chylothorax

[2]. However, when medical management fails, pleurodesis or ligation of

thoracic duct is the definitive treatment [3,4].

Case Report

A male newborn with a birthweight of 2.5 kg was born

with hydrops fetalis at 34 weeks of gestation by a cesarean section.

Antenatal ultrasound at 27 weeks showed bilateral pleural effusion with

ascites and polyhydramnios. Mother’s blood group was O Positive and

Indirect Coomb’s test was negative. Fetal echocardiography and

hemoglobin electrophoresis of the parents were normal.

|

|

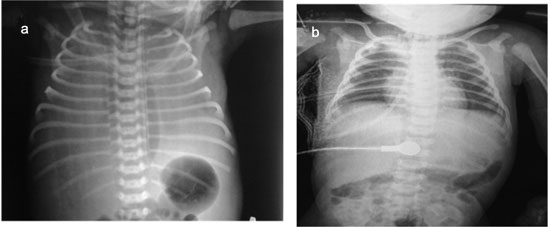

Fig. 1 Chest X-ray of patient

showing (a) bilateral pleural effusion after birth; (b) after

pleurodesis through the right sided intercostal tube.

|

The neonate had severe respiratory distress, and was

ventilated since birth. Chest X-ray revealed massive bilateral

pleural effusion, and required pleural tapping soon after birth. On day

2, bilateral intercostal drains (ICD) were inserted, because the

effusion was refilling after the initial pleural tap. Initial pleural

fluid was straw-colored, and had a white cell count of 1728 cells/mm3

with 90% lymphocytes and 10% polymorphs. Biochemical analysis showed

glucose 54 mg/dL, total protein 2.8 g/dL, LDH 580 IU/L and triglyceride

98 mg/dL. On day 3, as soon as the baby was fed milk, the pleural fluid

turned milky, and showed a triglyceride level of 171 mg/dL. A diagnosis

of congenital chylothorax was made, and the baby was kept NBM, and

started on TPN. In view of persistent intercostal drainage of chyle, the

baby was started on intravenous Octreotide infusion on day 4 of life at

1µg/kg/hour, which was slowly increased to 7µg/kg/hr. Although the left

ICD output stopped, right ICD output continued to be >100mL/day. In view

of this, on day-20, a decision was made to carry out pleurodesis on the

right side. Oxytetracycline with 2% lignocaine (Oxylab) was administered

into the right pleural cavity at a dose of 20 mg/kg through the ICD, and

the ICD was clamped for 2 hours. Due to failure of adequate response, a

2nd dose was given after 48 hours. The ICD output became nil after two

days. There were no adverse effects noted. Initially, the baby was fed

‘low fat milk’ (containing <0.2% fat per 100 g). Eventually, the baby

was breastfed, and discharged at 2 months of age. On follow up at 6

months of age, the baby was being breastfed, and was gaining weight

adequately. Baby had also attained milestones as per the corrected age.

Discussion

The conservative management of chylothorax is NBM and

prolonged TPN [3]. However, this is associated with morbidities such as

infections, hypoproteinemia and thrombosis. Although intravenous

octreotide has been used in treatment of chylothorax, but not all

effusions respond to it [2]. Pleurodesis or ligation of thoracic duct is

the definitive treatment option [3,4].

Our patient had a massive chylothorax with hydrops

fetalis, which can have a high mortality. The baby was premature, and

needed prolonged mechanical ventilation, including high-frequency

oscillator. Given the respiratory morbidity, the nutritional and

immunological complications, and a lack of response to octreotide, we

decided to perform pleurodesis.

Various agents (Povidone iodine, OK 432,

Tetracycline, Minocycline, Erythromycin and Talc) have been used for

pleurodesis. However, there are no definite guidelines for the agent of

choice [2]. Povidone iodine is known to be associated with renal side

effects [5], and is painful, and intravenous analgesia is needed.

oxytetracycline has been used in adults with malignant chylothorax at a

dose of 20mg/kg [6]. However, there is no previous experience of its use

in neonates.The mechanism of action of oxytetracycline is by initiation

of the inflammatory cascade by mesothelial cells after contact with the

chemical agent. There is activation of the coagulation cascade of the

pleura, fibroblast recruitment, activation, and proliferation, and

collagen deposition [7]. Although, lymphangiography and surgical

ligation are other therapeutic options; due to lack of technical

expertise, these could not be done in our patient. We suggest that

chemical pleurodesis with oxytetracycline is an effective treatment for

congenital chylothorax.

Contributors: AU, VK: were involved in patient

management and preparing the Manuscript. JM: reviewed the manuscript and

approved the final version.

Funding: None; Competing interest:

None stated.

References

1. Soto-Martinez M, Massie J. Chylothorax: Diagnosis

and management in children. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2009;10:199-207.

2. Das A, Shah PS. Octreotide for the treatment of

chylothorax in neonates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;9:CD006388.

3. Beghetti M, La Scala G, Belli D, Bugmann P,

Kalangos A, Le Coultre C. Etiology and management of pediatric

chylothorax. J Pediatr. 2000;136:653-58.

4. Merrigan BA, Winter DC, O’Sullivan GC. Chylothorax.

Br J Surg. 1997;84:15-20.

5. O Brissaud, L Desfrere, R Mohsen, MFayon,

JDemarquez. Congenital idiopathic chylothorax in neonates: chemical

pleurodesis with povidone-iodine (Betadine). Arch Dis Child Fetal

Neonatal Ed. 2003;88:F531-3.

6. Walker-Renard PB, Vaughan LM, Sahn SA. Chemical

pleurodesis for malignant pleural effusions. Ann Intern Med.

1994;120:56-64.

7. Antony VB, Rothfuss KJ, Godbey SW, Sparks JA, Hott

JW. Mechanism of tetracycline-hydrochloride-induced pleurodesis:

Tetracycline-hydrochlorid-stimulated mesothelial cells produce a

growth-factor-like activity for fibroblasts. Am Rev Respir

Dis.1992;146:1009-13.

|

|

|

|

|