|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2016;53: 1103-1105 |

|

Infantile Intraosseous

Maxillary Hemangioma

|

|

Divya Gupta, Ishwar Singh, Kavita Goyal and

*Parul Sobti

From Departments of Otorhinolaryngology and Head and

Neck Surgery, and *Pathology, Maulana Azad Medical College and

associated Lok Nayak Hospital, New Delhi, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Divya Gupta, Department of

Otolaryngology and Head & Neck Surgery, Maulana Azad Medical College and

associated Lok Nayak Hospital, New Delhi, India.

Email:

[email protected]

Received: October 09, 2015;

Initial review: October 28, 2015;

Accepted: August 06, 2016.

|

Background: Primary osseous hemangiomas of the facial skeleton mimic

malignancy. Their location in maxillary sinus, especially in infants is

extremely rare. Case character-istics: 1- month-old full term boy

with maxillary swelling. Observations: Biopsy from oral route

revealed hemangioma showing vascular channels lined by endothelial

cells. Patient improved on oral steroids. Message: Hemangiomas

should be considered as one of the differential diagnosis of unilateral

maxillary swelling in infants. Steroids may serve as the primary mode of

treatment as opposed to tumor excision.

Keywords: Corticosteroids, Maxilla, Tumor, Vascular

malformations.

|

|

H

emangiomas are benign tumors of the capillary

endothelium, and have varied clinical presentations. Intraosseous

hemangioma is a rare tumor accounting for 0.2-0.7% of all bone tumors

[1]. It is seen more frequently in vertebrae and calvarium, and is very

rare in jaw bones. Two-thirds of the jaw lesions occur in mandible and

one-third are found in maxilla [2]. Primary intraosseous maxillary

hemangioma in infants is extremely rare [3,4].

Case Report

A one-month-old male infant presented to us with

progressive right maxillary swelling and alveolar fullness, first noted

at 6 days of age. The child was born term, and had no significant

perinatal history. No functional deficits due to maxillary mass were

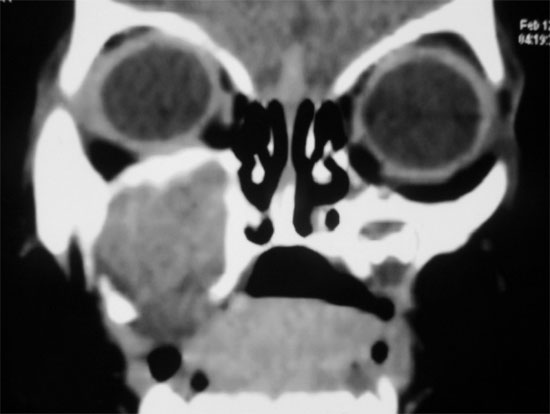

reported. Computed tomography (CT) revealed a heterogeneous, mildly

enhancing and expansile lesion of the right maxilla, replacing the right

maxillary sinus and alveolar ridge. Orbital contents were normal (Fig.

1).

|

|

Fig. 1 CT scan showing mildly

enhancing expansile lesion of the right maxilla.

|

We suspected malignancy, and performed a biopsy from

the swelling under general anesthesia via sublabial route. A fleshy

bleeding mass was seen from which biopsy was taken. The mass bled

profusely and the maxillary sinus was packed with sofragauze. The pack

was subsequently removed gently under short inhalational anesthesia

after two days. No bleeding was seen subsequently. Histopathological

examination of the mass revealed hemangioma showing vascular channels

lined by increased number of bland endothelial cells with no atypia or

mitosis. We treated the child with oral steroids (2 mg/kg/day) for two

months followed by gradual fortnightly tapering after the lesion

regressed. Maxillary fullness resolved in four months. The patient is

now well on regular follow-up.

Discussion

Infantile hemangiomas appear in infancy, grow till

one year of age, are more in females, and involute by adolescence. They

usually do not involve the bone, and are histologically characterized by

endothelial hyperplasia and increased number of mast cells with

expression of glucose transporter-1 (GLUT-1). Congenital hemangiomas;

however, have no postnatal proliferative phase [5]. This distinct

behaviour disqualifies the possibility of congenital hemangioma in this

child, as the maxillary swelling gradually increased in size. On the

other hand, vascular malformations are present at birth, have equal

gender distribution and usually become more prominent by puberty because

of slow progressive ectasia resulting from intraluminal flow. They do

not show endothelial hyperplasia and have normal number of mast cells

[4]. Venous malformations are very commonly mistaken to be hemangiomas.

It was easy to confuse hemangioma with vascular malformations in this

case as the presentation was congenital. We could not check GLUT-1

expression in this case because of unavailability of the marker kit but

the increased number of endothelial cells on histology, relatively rapid

increase in swelling size, and reversal of maxillary fullness on

treatment with steroids pointed strongly towards this lesion being a

hemangioma.

Intraosseous hemangiomas have a variable presentation

and occur mostly in second decade of life with a 2:1 preponderance in

females [6]. Incidentally, the two earlier reported cases of infantile

intraosseous maxillary hemangioma were both females [3,4].

CT of such lesions may show homogenous, non-calcified

masses that may remodel adjacent bone and show enhancement on contrast

administration [7]. It may also cause bony destruction leading to a

false impression of malignancy. Confirmation of the diagnosis requires

biopsy, but that is likely to result in profuse bleeding as in our case.

Hence, a very small antral window needs to be created for taking biopsy

from maxilla through sublabial route so that bleeding could be minimized

by pressure packing.

The treatment options of intraosseous hemangiomas

include complete excision of the tumor with reconstruction using various

materials. This may or may not be preceded by embolization [8]. However,

these recommendations have largely been made on the basis of treatment

of adult patients. Hemangiomas in infancy run growth phases of

progression and involution, and there is always a possibility of the

lesion resolving completely by itself with time. Moreover, any major

surgical manipulation in the bony framework of an infant may result in

permanent deformity. Keeping these points in consideration and with the

primary aim of arresting the growth of lesion and reducing the

likelihood of permanent disfigurement, we started treatment with oral

steroids, which resulted in a good response. Werle, et al. [3]

also reported complete resolution of maxillary hemangioma in an infant

girl with a ten-month course of oral steroids.

We suggest that possibility of hemangiomas should

always be considered in unilateral maxillary swelling in infants.

Conservative treatment with oral steroids may be the first line of

management in infantile intraosseous hemangiomas.

Contributors: DG and PS: case management and

drafting the manuscript; IS and KG: supervision of case and revision of

manuscript. All the authors approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Funding: None; Competing interests: None

stated.

References

1. Faeber T, Hiatt WR. Hemangioma of the frontal

bone. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;49:1018.

2. Mutlu M, Yaris N, Aslan Y, Kul S, Imamoglu M,

Ersoz S. Intraosseous noninvoluting congenital hemangioma of the

mandible in a neonate. Turkish J Pediatr. 2009;51:507-9.

3. Werle AH, Kirse DJ, Nopper AJ, Toboada EM. Osseous

hemangioma of the maxilla in an infant. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg.

2003;128:906-9.

4. Kadlub N, Dainese L, Hermine ACL, Galmiche L,

Soupre V, Lepointe HD, et al. Intraosseous hemangioma: semantic

and medical confusion. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;44:718-24.

5. Darrow DH, Greene AK, Mancini AJ, Nopper AJ.

Diagnosis and management of infantile hemangioma. Pediatrics.

2015;136:e1060-104.

6. Jeter TS, Hackney FL, Aufdemorte TB. Cavernous

hemangioma of the zygoma: report of cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg.

1990;48:508-12.

7. Koch BL, Myer CM. Presentation and diagnosis of

unilateral maxillary swelling in children. Am J Otolaryngol.

1999;20:106-29.

8. Yung YW, Sheng MG, Merrill RG, Sperry DW. Central Hemangioma of

the jaws. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;47:1154-60.

|

|

|

|

|