Sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation

(SANT) of the spleen is a rare benign vascular lesion. Since the first

description of this disease by Martel, et al. [1] in 2004,

several more cases have been described. Most cases of SANT have been

incidentally found in adults who were either completely asymptomatic or

had vague abdominal complaints [2]. We searched the MEDLINE database and

reviewed articles related to SANT published in English between January

1, 2004 and July 31, 2012. Reports of SANT in the pediatric age group

are rare, with only three cases reported to date and the youngest case

in an 11-year-old patient [3,4]. Herein, we present the pathological and

imaging evidence used to diagnose SANT in a 3-year-old child.

Case Report

A 3-year-old boy was admitted to our hospital with

complaints of abdominal pain and vomiting 2 hours after being involved

in a car accident. On examination, his vital signs were within normal

limits. Abdominal examination revealed upper abdominal tenderness with

mild muscle spasm. His medical history prior to the car accident and

family history were unremarkable.

The patient’s blood tests, including full blood

count, urea and electrolytes, liver and renal functions, were within

normal limits. Plain radiograph of abdomen ruled out perforation Because

the patient had a closed abdominal injury, suspicion of parenchymatous

intra-abdominal organ hemorrhage was maintained and computed tomography

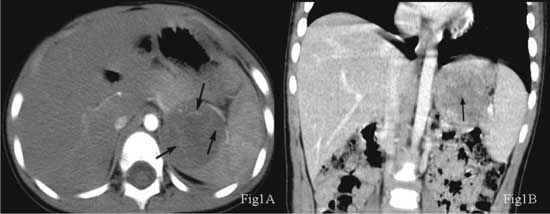

(CT) of the abdomen was performed (Fig. 1). Plain CT

images revealed a circular lesion with low density and a

well-circumscribed border. There was neither a cystic change nor

necrosis or calcification in the lesion. Contrast-enhanced CT scans

indicated an uneven nodular enhancement on the edge of the lesion and

vascular tissue-like bundles from the edge to the enhanced center. In

the portal and delayed phases, the lesion enhanced centripetally with a

wheel-like appearance. In the delay phase, most of the lesions and

spleen parenchyma had similar densities, and a star-like lesion could be

partially seen in the center. Carcinoemboroynic antigen and

a-feto-protein levels

were tested after the detection of tumor mass.

|

|

Fig. 1. (a) The arterial phase

showed nodular enhancement around the lesion and many enhanced

separations coming from the edge to the center (arrow); (b) The

portal vein phase showed a star-shaped, low-density area (arrow)

in the center of the mass, which had the appearance of a wheel

with spokes.

|

The patient underwent exploratory surgery with

partial splenectomy including total excision of the tumor mass. Gross

examination revealed a well-demarcated, solitary lesion, measuring 4×5×3

cm. The solitary lesion was connected to the spleen without a capsule

and was located on the surface of the spleen with a prominent nodular

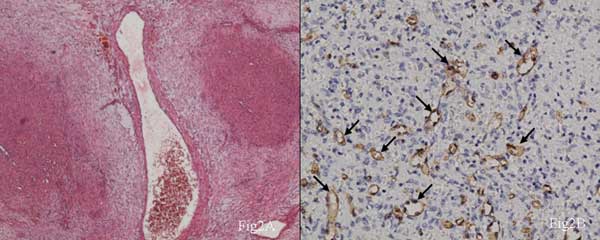

and lobulated shape (Fig. 2a). The tumor mass was chiefly

composed of connective tissue.

|

|

Fig. 2. (a) The fibrous tissue

was loose, including thick-walled blood vessels, but lacked

prominent collagen staining (HE staining, ×200); (b) Angiomatoid

modules were CD34 positive (HE, ×400).

|

The histopathologic findings revealed that some

fibrous tissue had hyaline or myxoid degeneration and some nodules had

merged to form irregular patterns. The thick-walled vessels contained

myxoid areas with infiltration of inflammatory cells. The lumen of the

vessels in the angiomatoid nodules was small and contained small lacuna

and sinusoid structures with vein-like and capillary-like vessels, which

were more prominent in the center of the nodule. Plasma cells,

eosinophilic leukocytes, and lymphocytes were scattered in the fibrous

stroma, primarily infiltrating the junction between the fiber and blood

vessels. Small amounts of hemorrhage and hemosiderosis were present in

the interstitial tissues and nodules (Fig. 2a).

Immuno-histochemical staining of the small blood vessels within the

angiomatoid nodules were positive for CD34 (Fig. 2b) and

CD31, but negative for glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1), Desmin, S100,

neuron-specific enolase (NSE), CD21, anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK),

and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). Smooth muscle actin (SMA)-positive venous

channels were found in between the epithelioid endothelial cells.

Irregular staining of vimentin and SMA was observed in the stroma. Some

cells in the lesion were CD68+ and CD8+, and the Ki-67+ percentage was

<5%. The observed histomorphology and staining profile supported the

diagnosis of SANT.

The patient recovered well without any post-operative

complications during the post-surgical period, and no evidence of

recurrence was observed during 20 months of follow-up.

Disscussion

Martel, et al. [1] named the condition

sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation (SANT) and reported 25

cases; SANT has since been gradually accepted as a distinct condition.

The pathogenesis remains unclear. Some people consider it a bleeding

hemangioma, with necrosis, inflammatory pseudotumor nodules, fibrous

tissue collagen, and nodules-like angiomatoid [5]. Immunohistochemical

staining of specimens from our patient was negative for GLUT1,

suggesting SANT to be a vascular malformation rather than a hemangioma.

Some researchers also believe that SANT is inflammatory pseudotumor-like

[4] and related to EBV infection[6]. The differential diagnosis of SANT

includes splenic hamartoma, for which the abnormal structure is mainly

composed of splenic red pulp without fibrous tissue dividing capillaries

into hemangioma sample nodules. Splenic hemangioma, which mainly

consists of capillary or spongy vessels, could appear as focal

infarction, hemorrhage, and fibrosis without hemangioma nodule formation

and be CD34+, CD31+, and CD8–. In 2010, Hou, et al. [5] reported

10 cases. SANT is typically considered more common in female adult

patients than in males. A literature search revealed four cases of SANT

in children (3 boys and 1 girl). Many patients with SANT are

asymptomatic, and usually the condition is identified incidentally

during physical examination [7]. About half of SANT patients present

with abdominal pain or other non-specific symptoms. Abdominal pain and

bloating have been reported in pediatric cases [3,4]. Li, et al.

[8] first reported CT imaging of SANT, showing the tumors were

low-density with calcifications and the condition progressively

enhanced. In the delayed phase, the lesion had the same density as the

adjacent tissue without a clear boundary between the spleen parenchyma.

The differential diagnoses include Gaucher’s disease, splenic hamartoma,

hemangioma, sarcoid, and a low-grade lymphoma and were difficult to rule

out completely before operation.

Asymptomatic patients with benign vascular splenic

lesions can be treated with conservative management, because SANT is

benign and there has been no report of malignant transformation. In

addition, surgical resection or laparoscopic resection of SANT results

in a good prognosis. In all reported cases of SANT, surgical resection

was both diagnostic and therapeutic. No recurrence or metastasis was

observed over a follow-up duration up to 9 years in the 25 cases

reported by Martel, et al. [1]. With follow-up durations of 7

months to 3 years [3,4], all previously reported pediatric patients

remained asymptomatic and healthy. Neither recurrence nor metastasis was

observed in the present case over a follow-up of 20 months.

Pediatricians and pediatric surgeons need to be aware

about the possibility of SANT occurring in asymptomatic pediatric

patients, though rarely.

Contributors: SZ: drafted the manuscript and

performed some clinical studies; WY: contributions to the conception and

design of the work and diagnosis of the disease HX: performed clinical

examinations, especially during the follow-up period; ZW: helped to

diagnose this disease.

Funding: None; Competing interests: None

stated.

References

1. Martel M, Cheuk W, Lombardi L, Lifschitz-Mercer B,

Chan JK, Rosai J. Sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation (SANT):

Report of 25 cases of a distinctive benign splenic lesion. Am J Surg

Pathol. 2004,28:1268-79.

2. Budzyñski A, Demczuk S, Kumiega B, Migaczewski M,

Mat³ok M, Zub-Pokrowiecka A. Sclerosing angiomatoid nodular

transformation of the spleen treated by laparoscopic partial splenectomy.

Videosurgery and Other Miniinvasive Techniques. 2011;6: 249-55.

3. Bamboat ZM, Masiakos PT. Sclerosing angiomatoid

nodular transformation of the spleen in an adolescent with chronic

abdominal pain. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:E13-6.

4. Vyas M , Deshmukh M, Shet T, Jambhekar N. Splenic

angiomatoid nodular transformation in child with inflammatory

pseudotumor-like areas. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2011;54:829-31.

5. Hou J, Ji Y, Tan YS, Shi DR, Liu YL, Xu C, et

al. Sclerosing angiomatoid nodulartransformation of spleenÿa

clinicopathologic study of 10 cases with review of literature. Chin J

Pathol. 2010;39:84-7.

6. Zhang MQ, Lennerz JK, Dehner LP. Granulomatous

inflammatory pseudotumor of the spleen: association with Epstein-Barr

virus. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol . 2009;17:259-63.

7. Falk GA, Nooli NP, Morris-Stiff GÿPlesec TP,

Rosenblatt S. Sclerosing Angiomatoid Nodular Transformation (SANT) of

the spleen: Case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case

Rep. 2012;3:492-500.

8. Li L, Fisher DA, Stanek AE. Sclerosing angiomatoid

nodular transformation (SANT) of the spleen: addtion of a case with

focal CD68 staining and distinctive CT features. Am J Surg Pathol.

2005;29:839-41.

9. Zeeb LM, Johnson JM, Madsen M S, Keating DP.

Sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation. Am J Roentgenol.

2009;192:W236-8.

10. Thacker C, Korn R, Millstine J, Harvin H, Van

Lier Ribbink JA, Gotway MB. Sclerosing angiomatoid nodular

transformation of the spleen: CT,MR,PET, and 99mTc-sulfur colloid SPECT

CT findings with gross and histopathological correlation. Abdom Imaging.

2010;35:683-9.