|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2014;51:

991-995 |

|

Parenting in Children and Adolescents with

Psychosis

|

|

S Srivastava, *I Sharma and MS Bhatia

From Departments of Psychiatry, University College of Medical

Sciences and Guru Teg Bahadur Hospital, Delhi; and *Institute of Medical

Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, UP; India.

Correspondence to: Dr Shruti Srivastava, Assistant Professor,

Department of Psychiatry, University College of Medical Sciences and

Guru Teg Bahadur Hospital, Delhi 110095, India.

Email:

[email protected]

|

Need and Purpose of review: Psychotic symptoms

appear in children and adolescents in the most crucial years, during the

individual’s career development. The challenges faced by parents of

psychotic children are in dealing with their disruptive behaviours,

negative symptoms, cognitive deficits, delusions and hallucinations.

This paper presents an overview of the childhood psychosis and how

parenting can be done effectively for this population.

Methods: Articles were retrieved from the

Medline, Cochrane database, Google Scholar, Medscape; using the search

terms ‘parenting and childhood psychosis’, and ‘childhood psychoses; and

standard textbooks were consulted.

Main conclusions: Educating parents how to

recognize early symptoms, explaining treatment adherence, side effects

of medications along with non-pharmacological measures like dealing with

expressed emotions, lowering expectations, enhancing social supports,

healthy lifestyle, and making patients independent. Awareness, early

identification and effective parenting for psychosis may help bridge the

wide gap between scarce skilled mental health professionals, inefficient

resources and large paediatric population.

Keywords: Childhood psychosis, Childhood schizophrenia,

Parenting, Severe mental illness.

|

|

S

chizophrenia and other psychotic illnesses, being

the third largest cause of disability worldwide, have major public

health importance [1]. Schizophrenia disorders are rare, especially in

children. Only about 4% of total cases of schizophrenia occur in

children <15, and only 0.1-1% occur in children under the age of 10. The

rate of onset increases sharply during adolescence, with the peak ages

of onset generally ranging from 15 to 30 [2]. In a meta-analysis done by

Kelleher, et al. [3] in 2012, prevalence of psychotic symptom

among children aged 9 to 12 was found to be 17% and among adolescents

aged 13 to 18 to be 7.5% [3].

Psychosis occurring in children and adolescents

persists for long before it is brought for treatment [4].There is

considerable data to show that if treated early, course and outcome of

psychosis will be better [5]. Parents/caregivers remain unaware of the

odd behaviors/social withdrawal /delusions/hallucinations. The scenario

becomes even worse when they do not know where to contact mental health

professionals, whose number is limited. They often have to travel long

distances in order to avail mental health services. Stigma associated

with mental illnesses also acts as a deterrent for the

parents/caregivers to seek information about mental illnesses or take

advice. Thus, children and adolescents remain in the psychotic state for

several years causing considerable burden to the parents/caregivers and

society at large.

Methods

The methodology involved review of articles retrieved

on Medline (using "parenting and childhood psychosis", "parenting and

psychosis", "childhood psychosis"), Google Scholar (relevant articles),

Cochrane database, and Medscape, restricted to English language, and

standard textbooks. In addition, we searched the references given in

these articles.

Etiology/risk factors

Schizophrenia and other childhood psychosis have a

multi-factorial etiology involving genetic and environmental factors

[6]. Genetics seem to play an important role in etiology of

schizophrenia. First-degree relatives of children with schizophrenia

have a higher prevalence rate of schizophrenia and schizophrenia

spectrum disorders. Family, twin and adoption studies support that

schizophrenia has a strong genetic component.

Neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia emphasizes

that the illness is the end stage of abnormal neuro-developmental

processes that began years before the onset of the illness [7].

Perinatal complications, alterations in brain structure and size, minor

physical anomalies, and disruption of fetal neural development,

especially during the second trimester of pregnancy, have been

correlated with the illness. Risk factors associated with childhood

psychosis include viral infections [8], childhood adversities [9],

famine [10], urban environment [11], cannabis [12], and migration [13].

Using magnetic resonance scans, Greenstein, et al.

[14] found out cortical thickness loss in childhood-onset schizophrenia

over 19-year follow up becomes localized with age to prefrontal and

temporal cortices, and the pattern of loss is more like that seen in

adult forms of the illness [14].

The neurotransmitter implicated in the patho-physiology

of schizophrenia is dopamine. Glutamate, serotonin and the N-methyl-D-aspartate

(NMDA) receptor dysfunction has also been implicated for production of

psychotic symptoms.

Early Diagnosis

Psychotic symptoms are present in children and

adolescents for extended period even before diagnosis [15]. Therefore,

it is important to recognize the prodromal symptoms for early

intervention. A follow-up study reported 35% risk of conversion to

psychosis in youth with prodromal symptoms (unusual thought content,

suspicion/paranoia, perceptual anomalies, grandiosity, and disorganized

communi-cation) [16]. The study found that the five features assessed at

baseline that contributed uniquely to the prediction of psychosis are

genetic risk for schizophrenia with recent deterioration in functioning,

higher levels of unusual thought content, higher levels of

suspicion/paranoia, greater social impairment, and a history of

substance abuse.

The symptomatology of childhood psychosis differs

from that in adults [17]. Symptoms frequently reported in psychotic

children are: speech disturbances, inability to distinguish dreams from

reality, visual and auditory hallucinations, vivid and bizarre thoughts

and ideas, diminished interest, confused thinking, extreme moodiness,

odd behavior, stereotypy, dis-inheriting ideas that others are out to

get them, confusion of television with reality, severe problems in

making and keeping friends. Hallucinations and delusions have typically

been viewed as symptoms of psychosis [18]. Cognitive deficits are

reported in childhood psychosis similar to adults, which include

deficits in attention, learning and abstraction [19].

For diagnosing schizophrenia, DSM-5 criteria lays

down that two (or more) out of the following should be present during a

one-month period (or less if successfully treated) (a) delusions

(b) hallucinations, (c) disorganized speech, (d)

grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior, and (e) negative

symptoms. It should further qualify for Symptoms either a, b or c must

be present out of the two to make diagnosis of Schizophrenia. Continuous

signs of disturbance must persist for at least 6 months, which includes

both periods of prodromal and residual symptoms. Attenuated psychosis

syndrome is included in the appendix for future research [20].

Challenges Faced by Parents of Childhood Psychosis

Taking care of a psychotic child is a challenging

task for the family members, especially parents. Parental support during

ongoing treatment predicts the prognosis of the psychotic illness in

children. Direct support provided by the mental health professionals to

the family members through information sharing, and indirect support

provided by the other family members and support groups is found to have

positive associations with family members‘experience of care-giving.

Care-giving gains in the form of becoming more sensitive to persons with

disabilities, and improving relationships with the patients should be

emphasized [21].

Faulty communication patterns have been described in

families of psychotic patients. Communication deviance that compromises

the development and sharing of meaning between the parent and the

offspring and leading to the consequent breakdown in communication has

long been suggested as a potential risk factor for the development of

psychosis [22]. The expressed emotion which includes criticism,

hostility and emotional over-involvement is considered to be an adverse

family environment. High degrees of expressed emotions is linked to the

relapse of the illness and puts the patient in stress [23].

Treatment

Antipsychotics are used in the treatment of children

and adolescents suffering from psychosis. No antipsychotic is superior

to other in terms of efficacy. The chance of relapse is high if the

medication is stopped one to two year following relapse. Routine

monitoring of the following parameters have been recommended like

weight, height, waist and hip circumference, pulse, blood pressure,

fasting blood glucose levels, glycosylated hemoglobin, blood lipid

profile, prolactin levels, movement disorders, diet, nutrition, physical

activity, side-effects, adherence, and efficacy. Treatment-resistant

schizophrenia in children and adolescents requires clozapine [24].

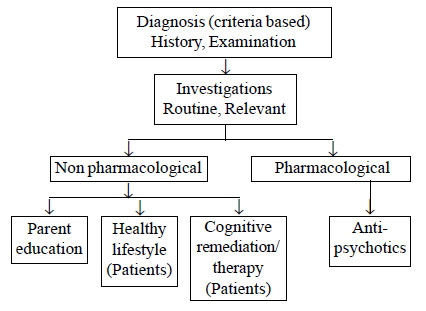

Fig.1 shows an algorithm for the management of children and

adolescents suffering from psychosis.

|

|

Fig. 1 Management of children and

adolescents suffering from psychosis.

|

Both pharmacological and non-pharmacological

interventions are required for effective and early treatment of children

and adolescents. Early treatment is of paramount importance.

Antipsychotics are very useful in the treatment of psychosis. After the

acute symptoms of psychosis subside with these medications, the child

may benefit from counseling and psychosocial interventions.

The following non-pharmacological interventions have

been found to be efficacious [25].

Cognitive remediation (CR): It aims to arrest or

reverse the cognitive impairments in attention, concentration and

working memory. A combination of ‘procedural’ and ‘effortless learning’,

‘targeted reinforcement’ and massed practiced appears to facilitate

cognitive flexibility and memory in patients with schizophrenia [26].

Parents are advised to break down information and tasks into small

manageable parts to reduce demands on working memory.

Cognitive Behavior therapy (CBT): The therapeutic

techniques used for patients with psychosis are based on the general

principles of CBT. Links are established between thoughts, feelings, and

actions in a collaborative and accepting atmosphere. Agendas are set and

used but are generally more flexibly developed than in traditional CBT.

What is Needed?

Children and adolescents constitute 40% of the

population of India. First and foremost is the need to ease access to

care. Appropriate care and necessary information should be available at

the doorstep of the service users. For this, an infrastructure of proper

referral and care system should be in place. The proposed model of care

involving interventions at primary, secondary and tertiary levels are

required for our country in the following way:

Primary level: Following professionals can

provide care at the primary level. There is evidence to suggest the

involvement of Non specialist health workers in bridging the gap between

the scarcity of trained psychiatrists and limited resources for low and

middle income countries [27].

Health professionals can provide following services

at primary level:

• Create awareness about psychosis.

• Removing myths and misconceptions about mental

illness in general and psychosis in particular.

• Awareness about pre-morbid indicators of

psychosis.

• Psycho-education about psychosis.

• Early Identification and distribution of parent

education materials.

• Referral to higher center for timely treatment

after early identification.

District level

• Psychiatrists (under District Mental Health

Program) trained in the early diagnosis/ treatment.

• Availability of Generic psycho tropics which

are distributed free of cost.

• Referral to tertiary care center in case of

Severe Mental Disorder which requires specialty management in a

mental health Institute.

Tertiary level: Multidisciplinary teams of mental

health professionals for early identification and intervention as

already exist in all teaching hospitals should be further strengthened

like other Asian countries e.g., Singapore [28]. Allocation of

funds to improve the quality and standards of research on psychosis

should be allocated.

Guidelines for Parents

Having a child or an adolescent with psychosis is a

difficult situation and a life-long challenge. Parents who are the

primary caregivers most of the time feel overwhelmed and unprepared for

facing this situation. It is thus of paramount importance that parent

education material should be made available in the local languages (Box

I).

Box 1: Guidelines for Parents of Children and Adolescents Suffering From Psychosis

|

• |

Psychosis is a severe form of mental disorder in which contact

with the reality is lost. It is associated with abnormalities

and oddities of behavior, where children just do not seem like

themselves. |

|

• |

What causes it?

|

|

It is multifactorial involving genes, infections, cannabis,

stress, neurotransmitters etc.

|

|

• |

How do we (parents/caregivers) recognize it?

|

|

It may begin with changes in behavior like social withdrawal,

decline in school performance. The child may have active

symptoms like he/she may hear or see something which is

perceived in the absence of stimulus or may develop false, fixed

belief that “people want to harm me’’. Deterioration in previous

functioning with disturbance in sleep and appetite.

|

|

• |

What is the treatment?

|

|

Antipsychotic drugs are the mainstay of treatment. Several

non-pharmacological measures are also useful. Early treatment is

of paramount importance; adherence to treatment is

essential. |

|

• |

What can we do?

|

|

Reduce expressed emotions like criticism, hostility and

over-involvement. Encourage-ment, praise for desired behaviors,

increase social support, inculcate hobbies, reduce burden of

studies thereby minimize stress, try to make them independent. |

|

• |

What is the future of my child?

|

|

With long term treatment, full recovery is possible. With timely

help, many youth grow up to lead healthy, productive lives. |

The key point to remember is that psychosis and

schizophrenia occurring in children and adolescents have poor outcome

[29].The best way to minimize its impact is early identification and

treatment. While relapses may occur from time to time, the effects of a

psychotic episode are decreased if symptoms are identified within the

first six months of onset. There is research evidence to suggest better

course and outcome of schizophrenia in developing countries as compared

to developed countries [30].

High levels of parental involvement (parental

understanding of their children’s problems, and parental knowledge of

their children’s free-time activities) is associated with decreased

outcome of poor mental health in India’s Nationally representative

global survey done on 6721 school going adolescents in 2007

[31].Traditionally, in India, the responsibility of care and protection

of children is provided by the families and the communities. Both the

prevention and promotion of child mental health in a country with low

socio-economic status can be achieved by supporting parenting [32].

Authoritative parenting and parental warmth, especially in Indian

families, are the most adaptive parenting styles that act as protective

factors for the development of psychopathology and positive adjustment

among adolescents [33]. Health education of parents and parental

counseling play a key role in early intervention and promotion of

positive mental health of children and adolescents [34].

Conclusions

Child and adolescent mental health services are

hardly available in a low income country like India. The need for the

hour is to strengthen the mental health services through innovative

strategies that are cost-effective. Awareness, early identification and

effective parenting of pediatric psychosis may help bridge the wide gap

that exists between scarce skilled mental health professionals,

inefficient resources, and large population of children and adolescents

in developing countries.

Contributors: SS: literature search, designed and

prepared the initial draft; IS: conceived, designed, revised the draft;

MSB: designed, revised the draft. All authors approved the final

version. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the

work.

Funding: None; Competing interests: None

stated.

References

1. World Health Organization (WHO). World Health

Report 2001. Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope. Geneva: WHO;

2002.

2. Remschmidt HE, Schulz E, Martin M, Warnke A, Trott

GE. Childhood onset schizophrenia: History of the concept and recent

study. Schizophr Bull. 1994;20:727-45.

3. Kelleher I, Connor D, Clarke MC, Devlin N, Harley

M, Cannon M. Prevalence of psychotic symptoms in childhood and

adolescence: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based

studies. Psychol Med. 2012;42:1857-63.

4. Dominguez MD, Fisher HL, Major B, Chisholm B,

Rahaman N, Joyce J , et al. Duration of untreated psychosis in

adolescents: Ethnic differences and clinical profiles. Schizophr Res.

2013;150:526-32.

5. Amminger GP, Henry LP, Harrigan SM, Harris MG,

Alvarez-Jimenez M, Herrman H, et al. Outcome in early-onset

schizophrenia revisited: findings from the Early Psychosis Prevention

and Intervention Centre long-term follow-up study. Schizophr Res.

2011;131:112-9.

6. Kirkbride JB, Fearon P, Morgan C, Dazzan P, Morgan

K, Tarrant J, et al. Heterogeneity in incidence rates of

schizophrenia and other psychotic syndromes: findings from the 3-center

AeSOP study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:250-8.

7. RapoportJL, Giedd JN, Gogtay N. Neurodevelopmental

model of schizophrenia: update 2012. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17:1228-38.

8. Rantakallio P, Jones P, Moring J,Von Wendt L.

Association between central nervous system infections during childhood

and adult onset schizophrenia and other psychoses: a 28-year follow-up.

Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26:837-43.

9. Varese F, Smeets F, Drukker M, Lieverse R,

Lataster T, Viechtbauer W, et al. Childhood adversities increase

the risk of psychosis: a meta-analysis of patient-control,

prospective-and cross-sectional cohort studies. Schizophr Bull.

2012;38:661-71.

10. Xu MQ, Sun WS, Liu BX, Feng GY, Yu L,Yang L,

et al. Prenatal malnutrition and adult schizophrenia: further

evidence from the 1959-1961 Chinese famine. Schizophr Bull.

2009;35:568-76.

11. Van Os J, Hanssen M, Bijl RV, Vollebergh W.

Prevalence of psychotic disorder and community level of psychotic

symptom. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:663-8.

12. Arseneault L, Cannon M, Poulton R, Murray R,

Caspi A, Moffitt TE. Cannabis use in adolescence and risk for adult

psychosis: longitudinal prospective study. BMJ. 2002;325:1212-3.

13. Veling W. Ethnic minority position and risk for

psychotic disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2013;26:166-71.

14. Greenstein D, Lerch J, Shaw P, Clasen L, Giedd J,

Gochman P, et al. Childhood onset schizophrenia: cortical brain

abnormalities as young adults. J Child Psychol Psychiatry.

2006;47:1003-12.

15. Sikich L. Diagnosis and evaluation of

hallucinations and other psychotic symptoms in children and adolescents.

Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2013;22:655-73.

16. Cannon TD, Cadenhead K, Cornblatt B, Woods SW,

Addington J, Walker E, et al. Prediction of psychosis in youth at

high clinical risk: a multisite longitudinal study in North America.

Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:28-37.

17. Tolbert HA. Psychoses in children and

adolescents: a review. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996; 57 (Suppl 3):4-8;46-7.

18. Polanczyk G, Moffitt TE, Arseneault L, Cannon M,

Ambler A, Keefe RS, et al. Etiological and clinical features of

childhood psychotic symptoms: results from a birth cohort. Arch Gen

Psychiatry. 2010; 67:328-38.

19. Courvoisie H, Labellarte MJ, Riddle MA. Psychosis

in children: diagnosis and treatment. Dialogues Clin Neurosci.

2001;3:79-92.

20. American Psychiatric Association (APA).

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. DSM-5.

Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

21. Chen FP, Greenberg JS. A positive aspect of

caregiving: the influence of social support on caregiving gains for

family members of relatives with schizophrenia. Community Ment Health J.

2004;40:423-35.

22. de Sousa P, Varese F, Sellwood W, Bentall RP.

Parental communication and psychosis: A meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull.

2014;40:756-68.

23. Hooley, JM. Expressed emotion and relapse of

psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2007;3: 329-52.

24. Kranzler HN, Cohen SD. Psychopharmacologic

treatment of psychosis in children and adolescents: efficacy and

management. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2013;22:727-44.

25. Schimmelmann BG, Schmidt SJ, Carbon M, Correll

CU. Treatment of adolescents with early-onset schizophrenia spectrum

disorders: in search of a rational, evidence-informed approach. Curr

Opin Psychiatry. 2013;26:219-30.

26. Wykes T, Reeder C, Corner J,Williams C, Everitt

B. The effects of neurocognitive remediation on executive processing

inpatients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25:291-7.

27. van Ginneken N, Tharyan P, Lewin S, Rao GN, Romeo

R, Patel V. Non-specialist health worker interventions for mental health

care in low-and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database Syst

Rev.2011; CD009149.

28. Verma S, Poon LY, Subramaniam M, Abdin E,Chong

SA. The Singapore Early Psychosis Intervention Programme (EPIP): A

programme evaluation. Asian J Psychiatr. 2012;5:63-7.

29. Deakin J, Lennox B. Psychotic symptoms in young

people warrant urgent referral. Practitioner. 2013;257:25-8.

30. Kulhara P, Shah R, Grover S.Is the course and

outcome of schizophrenia better in the ‘developing ‘world?Asian J

Psychiatry. 2009;2:55-62.

31. Hasumi T, Ahsan F, Couper CM, Aguayo JL, Jacobsen

KH. Parental involvement and mental well-being of Indian adolescents.

Indian Pediatr. 2012;49:915-8.

32. Shastri PC. Promotion and prevention in child

mental health. Indian J Psychiatry. 2009;51:88-95.

33. Patel V, Flisher AJ, Nikapota A, Malhotra S.

Promoting child and adolescent mental health in low and middle income

countries. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008; 49:313-34.

34. Shrivastava SR, Shrivastava PS, Ramasamy J.

Childhood and adolescence:Challenges in mental health. J Can Acad Child

Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;22:84-5.

|

|

|

|

|