|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2012;49: 985-986

|

|

Tracheobronchopathia Osteochondroplastica in a

5-year-old Girl

|

|

Clemax Couto Sant´Anna, Paulo Pires-de-Mello*, Maria de Fátima Morgado*

and

Maria de Fátima Pombo March

From the Faculty of Medicine of Federal University of

Rio de Janeiro and *Respiratory Endoscopy Department of Instituto

Fernandes Figueira. Rio de Janeiro, RJ. Brazil.

Correspondence to: Clemax C Sant´Anna, R Cinco de

Julho 350 ap. 604 – Copacabana, 22051-030.

Rio de Janeiro, RJ. Brazil. Email:

[email protected]

Received: February 14, 2012;

Initial review: March 02, 2012;

Accepted: July 23, 2012.

|

Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica (TO) is considered an orphan

disease with exceptional occurrence in children. We report a 5-year-old

female child who was referred to us with chronic cough and recurrent

pneumonia. After several investigations, bronchoscopy showed multiple

nodules in the tracheobronchial lumen, whose distribution was consistent

with TO. The patient was followed for four years, with no change in the

pattern of the disease.

Key words: Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica,

Recurrent pneumonia.

|

|

Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica

(TO), also known as tracheopathia chondro-osteoplastica or

tracheopathia osteoplastica, is a rare chronic disease of

undetermined etiology. It stems from osteocartilaginous metaplasia

and is characterized by an bronchoscopic finding of multiple

subepithelial nodules that project into the tracheobronchial lumen

and does not affect the lungs or other organs. The nodules may be

present from the larynx to the peripheral bronchi in the

anterolateral tracheal wall. In general, the posterior wall is

spared. This peculiarity is exclusive of this disease and allows the

exclusion of other differential diagnoses. TO is often an endoscopic

finding and its prevalence in bronchoscopic studies is estimated to

range from 1:125 to 1:6000 [1-3]. To date, less than 400 cases have

been reported in the literature, and only four were in children

[1,2,4].

Diagnosis can be made from the typical endoscopic

finding of the disease, dispensing biopsy [1,5,6]. Biopsy, when

done, shows ossification or calcification of the bronchial submucosa

[6].

Case Report

A 5-year-old female child with chronic cough and

a history of chronic cough and recurrent pneumonia since age 3 years

was referred to us. The first episode consisted of right upper lobe

pneumonia that progressed to pneumatocele, resulting in a permanent

cicatrical atelectasis. The other respiratory infection episodes in

the following year were also interpreted as pneumonia but were

based, apparently, on a radiographic image that had persisted since

the first episode: chronic atelectasis of the left lower lobe and

adhesive atelectasis in the right lung. Further examination showed

no signs of atopy. Her pulmonary auscultation was normal. The child

was HIV seronerative and had a normal immunoglobulin profile.

Tuberculin skin test was 6 mm. At the time she was treated as an

outpatient and the disease course was favorable, despite frequent

coughing and two more episodes of respiratory infection and cervical

adenitis treated with antibiotics. At age seven years, she underwent

rigid bronchoscopy, which showed widespread nodular mucosal

irregularity extending from trachea into bronchial tree; irregular

mucosa, intensely friable when touched by the instrument. The left

lower lobe bronchus was not obstructed. Bronchial aspirate was

negative for bacteria (including acid-alcohol-fast bacilli and M.

tuberculosis) and yeasts. The findings were consistent with TO.

Biopsy of bronchial mucosa, which did not include cartilage,

evidenced a nonspecific, chronic inflammatory process with intense

lymphoid hyperplasia in the lamina propria and prevalence of

neutrophils. Outpatient care consisted of occasional courses of

antibiotics and respiratory physiotherapy. At age 8 years,

spirometry was normal. The patient responded well, with occasional,

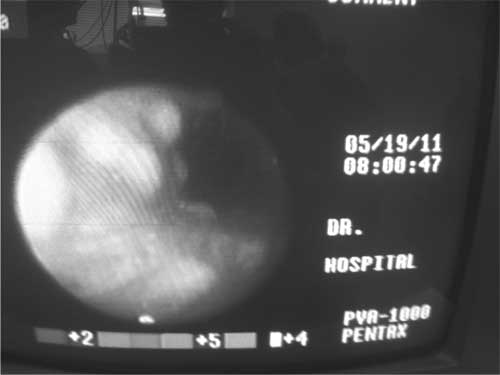

mild respiratory infections. After four years, flexible bronchoscopy

showed similar findings (Fig. 1). The patient is now

11 years old, continues to be followed as an outpatient and has a

favorable course.

|

|

Fig.1 Nodular mucosal irregularity

of trachea observed on flexible bronchoscopy.

|

Discussion

The present case is relevant because of the

rarity of this disease in children. Moreover, TO lesions did not

deteriorate after four years of follow-up. The disease may remain

stable for a long time or progress insidiously for many years. Rapid

progression leading to tracheal obstruction is singular [2,7].

The clinical findings vary. TO may be mistaken

for asthma because of the wheezing caused by decreased bronchial

diameter. TO may also cause chronic cough [5], dyspnea and

hemoptysis [6] but most patients are asymptomatic [1,6].

This patient had chronic atelectasis of the left

lower lobe, consequent of recurrent pneumonia. Atelectasis could be

explained by obstruction of the bronchial lumen by TO nodules since

their promotion of secretion retention established the vicious cycle

of atelectasis and pneumonias. The patient did not have asthma,

which could be considered an associated condition. However, her

wheezing episodes could be attributed to the partial obstruction of

the bronchial tree by multiple nodules [2,5,7].

The tracheal and bronchial nodules bled easily

and were soft, similar to other reports [1,5]. Since the nodules

bled easily during endoscopy, the tissue collected for biopsy during

the two endoscopic examinations was more superficial. Hence, the

nodules contained no cartilage, only nodular neutrophilic

arrangements [5]. This result ruled out other diseases like

tuberculosis, hypertrophy of bronchial associated lymphoid tissue,

sarcoidosis, etc.

There is no specific treatment for TO. When there

is evidence of bronchial infections, the patient should be treated

with antibiotics, as presently done. The present patient was never

prescribed inhaled corticosteroids, even though they have already

been used for TO treatment in some case series [6,7].

Acknowledgments: Drs. Barbara Almeida and

Eliane Castelo Branco from Clementino Fraga Filho Universitary

Hospital (UFRJ) and Dr. Roberta Gonçalves Silva from IPPMG - Federal

University of Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Contributors: CS´A: drafted and edited the

manuscript; MFM and PPM were involved in endoscopic procedure and

documentation of the case report. MFPM: interpreted the results and

drafted the manuscript. All authors held final responsibility for

the decision to submit for publication.

Funding: None; Competing interests:

None stated.

References

1. Chroneau A, Zias N, Gonzalez AV, Beamis Jr JF.

Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica: an underrecognized

entity? Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2008;69:65-9.

2. Lazor R, Cordier JF. Tracheobronchopathia

osteochondro-plastica. Orphanet encyclopedia, June 2004. Available

at http://www.orpha.net/data/patho/GB/uk-TO.pdf. Accessed on 27

January, 2012.

3. Wilks S. Ossific deposits on larinx, trachea

and bronchi. Trans Pathol Soc London. 1857;8:88.

4. Simsek PO, Oxcelik U, Demirkazik F, Unai OF,

Diclehan O, Aslan A, et al. Tracheobronchopathia

osteochondro-plastica in a 9-year-old girl. Pediatr Pulmonol.

2006;41:95-7.

5. Willms H, Wiechmann V, Sack U, Gillissen A.

Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica: a rare cause of chronic

cough with haemoptysis. Cough. 2008;4:4.

6. Ryu JH, Maldonado F, Tomassetti S. Idiopathic

tracheopathies. Eur Resp Mon. 2011;54:187-200.

7. Pinto JA, Silva LC, Perfeito DJP, Soares JS.

Ostheochondroplastic tracheobronchopathy: report on 2 cases and

bibliographic review. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;76:789-93.

|

|

|

|

|