Case Reports

Case 1: A 5 year old boy was admitted with

history of abnormal behavior, which started abruptly 3 days prior to

admission. While watching television at home, he suddenly complained that

some people were pursuing him. After this episode he was always frightened

and clung to his mother throughout the day. He became very restless,

irritable and developed violent tendencies. His speech was irrelevant and

often repetitive. He exhibited bizarre behavior like running around and

going up and down the stairs repeatedly. He refused to go to sleep and

frequently woke up crying. He refused to go to school saying that unknown

persons were pursuing him. He did not say whether he could see the people

or hear their voices.

One week prior to the onset of the symptoms he had

upper respiratory infection, which was relieved by oral medications. There

was history of recurrent otitis media up to the age of two years. The

parents did not notice any obvious hearing defect in the past. It was

reported that the child preferred right ear to listen to telephone and

sometimes gave inconsistent or irrelevant answers to questions, which the

parents attributed to carelessness.

He was an only child, born by normal delivery to

nonconsanguinous parents. His developmental milestones were normal. He was

studying in the UKG and was performing well at school. There was no family

history of mental illness.

On mental status examination he was conscious and

oriented. He was very anxious and was always clinging to his mother. His

speech was coherent but he cried frequently and answered questions after

repeated cajoling and sometimes gave irrelevant answers. His mood varied

from anxious to irritable. There were no perceptual abnormalities.

Although he had persecutory ideas they were inconsistent and their

delusional nature could not be ascertained due to his age. Since the child

was not cooperative, detailed hearing assessment could not be done. There

was no other cranial nerve involvement or focal neurological defect. Deep

tendon reflexes were normal and plantar reflex was bilaterally flexor.

His routine blood and urine examinations and CSF

analysis were normal. Brainstem auditory evoked response (BAER) evaluation

was suggestive of mild sensorineural hearing loss on the right side and

severe sensorineural hearing loss on the left side. Transient otoacoustic

emission (TOAE) test results indicated abnormal cochlear function on both

sides. MRI brain scan showed hyperintense lesions in both posterior

temperoparietal and parietal sub cortical areas on T2 and FLAIR images

which were iso- intense on T1 weighted images and were suggestive of ADEM.

He was treated with intravenous methylpre-dnisolone

30mg/kg/day for three days. Haloperidol 0.125mg twice daily for four weeks

was given to control the behavior. He improved gradually and complete

recovery occurred within a month. On follow up at six months he was using

a hearing aid on the left side and had average academic performance.

Case 2: A 10 year old girl was admitted with 3 day

history of excessive and irrelevant speech. She also complained of people

trying to attack her and her mood fluctuated rapidly. She refused to go to

school and became aggressive on minor provocations. Her sleep was

disturbed, but appetite was normal. One week prior to these symptoms she

had mild upper respiratory infection. She was born of third degree

consanguineous marriage and her developmental milestones were normal. She

was studying in the fifth standard and had good academic performance. She

was the youngest of four siblings. Her mother had psychotic illness

immediately after the second delivery, which subsided with treatment.

On examination she was conscious and oriented to time,

place and person. Her speech was coherent. Although she answered questions

relevantly, there was pressure of speech and flight of ideas. The reaction

time was shortened. Her mood was predominantly elated and occasionally

irritable. There were no definite delusions or hallucinations. Physical

examination including nervous system examination was normal.

Routine blood investigations, liver function tests, CSF

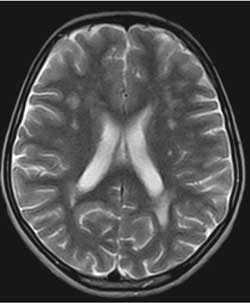

study and EEG were normal. The MRI images of brain showed focal

hyperintense areas of varying sizes in the bilateral centrum semiovale,

fronto-parietal and occipital white matter in T2 and FLAIR sequences which

were hypointense in T1 sequences (Fig.1).

|

|

Fig. 1. MRI Image: T2 axial section

shows white matter hyperintensities. |

She was treated with intravenous methylpre-dnisolone

30mg/kg/day for three days and then switched on to oral prednisolone for

four weeks. Risperidone 0.5mg twice daily was given to control the

behavior. Her symptoms improved within two days and complete recovery

occurred after two to three weeks.

Discussion

The first child had acute onset of behavior change

characterized by excessive anxiety, restlessness, irritability,

excitement, irrelevant talk and variable mood. The persecutory delusions

were present for only brief periods. The clinical features were consistent

with a diagnosis of acute and transient psychotic disorder (F23.8) as per

the ICD-10 diagnostic criteria(6). The second child had pre-dominantly

mood symptoms. Although she had pressure of speech and flight of ideas,

the criteria for manic episode could not be satisfied. The unstable

clinical picture favored the diagnosis of acute and transient psychotic

disorder (F23.8). The MRI findings in both cases were diagnostic of ADEM.

The hearing defect in the first child was present before the illness and

hence could not be attributed to ADEM.

Psychosis is an uncommon presentation of ADEM. A

Medline database search from 1965 to 1999 identified 9 patients who

presented with acute psychosis(7). After 1999, few more cases of ADEM

presenting with psychiatric manifestations have been reported (8,9). To

the best of our knowledge, ADEM in children presenting as acute psychotic

episode has not been reported from India.

Onset of psychotic disorder during childhood is very

rare and organic causes should be ruled out in these cases. ADEM is one

possibility to be considered in such situations and MRI scan can be

helpful.

Acknowledgment

Dr PT Gaurisanker for interpretation of MRI reports.

1. Murthy JM. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis.

Neurol India 2002; 50: 238-243.

2. Garg RK. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis.

Postgrad Med J 2003; 79: 11-17.

3. Madan S, Aneja S, Tripathi RP, Batra A, Seth A,

Taluja V. Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis – A case series. Indian

Pediatr 2005; 42: 367-371.

4. Murthy SNK, Faden HS, Cohen ME, Bakshi R. Acute

disseminated encephalomyelitis in children. Pediatrics 2002; 110: e21-e21.

5. Johnston VM. Neurodegenerative disorders of

childhood. In: Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Jenson HP, Stanton BF. Eds.

Nelson Text Book of Pediatrics. 17th Ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007. p.

2499 – 2507.

6. World Health Organization. The ICD–10 Classification

of Mental and Behavioral Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic

Guidelines. Geneva: WHO; 1992.

7. Nasr JT, Andriola MR, Coyle PK. ADEM: Literature

review and case report of acute psychosis presentation. Pediatr Neurol

2000; 22: 8-18.

8. Lin WG, Lirng JF, Chang FC, Chen SS, Luo CB, Teng

MM, et al. Sequential MR studies of a patient with white matter

disease presenting psychotic symptoms: ADEM versus single-episode MS.

Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2001; 17: 161-166.

9. Habek M, Brinar M, Brinar VV, Poser CM. Psychiatric manifestations

of multiple sclerosis and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Clin

Neurol Neurosurg 2006; 108: 290-294.