Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (AHEI) is a benign,

small vessel vasculitis of young children with characteristic skin

findings. The cutaneous findings are dramatic, both in appearance and

rapidity of onset; histopathology is characterized by leukocytoclastic

vasculitis(LCV). Since 1913, when AHEI was first reported, only about 100

case reports have appeared in the literature(1). The condition is also

described as Finkelstein’s disease(2), or Seidlmayer syndrome.

Case Report

This 18 month old girl presented with features of viral

upper respiratory tract infection for 4-5 days followed by edema starting

from feet and progressing to all four limbs. The patient also showed

erythematous palpable spots, first on the lower limbs that progressed to

the upper limbs, face and ears and were absent from the trunk (Fig.

1). The patient was receiving an unidentified oral antibiotic,

which was administered after the onset of rash and edema. There was no

history of pain abdomen, irritability, hematuria, refusal to feed or

recent vaccination. There was no history of similar illness in the family.

On examination, the child was active and playful with stable vitals and

mild fever; the blood pressure was normal. Skin examination showed

erythmatous, palpable, pupuric lesions over the legs, gluteal region,

upper limbs, face and ears varying in size from 0.5 to 4 cm in diameter.

There was edema of upper and lower limbs; no tenderness was elicited.

Systemic examination was normal. During hospital stay, there were multiple

crops of these purpuric lesions. Investigations showed normal blood counts

and blood levels of urea, creatinine and electrolytes; urinalysis was

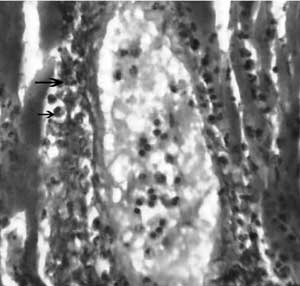

normal. Blood culture was sterile and chest x-ray was normal. Skin biopsy,

on day 3 of admission, showed mild hyperkeratosis with spongiosis in

epidermis. Dermis showed edema and periadenexal inflam-matory infiltrate.

Small blood vessels showed focal neutrophilic infiltrate and concentric

thickening of thin walls, with nuclear dust and fibrinoid changes; the

features were compatible with the diagnosis of leukocytoclastic vasculitis

(Fig.2). Immuno-fluorescence study was not done. The patient

was given symptomatic treatment and recovered within 10 days.

|

|

|

Fig.1 Typical erythematous, papular and

target like skin lesions characteristic of AHEI. Note the presence

of edema over both the legs.

|

Fig.2 Photomicrograph showing thickened

vessel wall with infiltration by neutrophils. Note the presence of

nuclear dust. (H&E; 400X) |

Discussion

Krause, et al.(3) reported a series of 5

patients and proposed clinical criteria for the diagnosis of AHEI as: age

less than two years, purpuric or ecchymotic target like lesions with edema

on the face, auricles and extremities with or without mucosal involvement,

lack of systemic disease and visceral involvement, spontaneous recovery

within few days or weeks(3). Our case fulfills all

above criteria along with consistent findings of skin biopsy.

On histopathological examination of skin, small blood

vessels in the dermis show perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate with

numerous scattered nuclear fragments called nuclear dust.

Histopathological findings in Henoch Schonlein purpura are similar to

AHEI. However, IgA deposition is seen in only 10-35% cases of AHEI.

Immunofluroscence studies have shown deposition of fibrinogen, C3, IgA,

IgG, IgM, IgE in and around small blood vessels.

AHEI is an uncommon disease. This may reflect either a

low incidence or underdiagnosis. Other reason for its rarity could be that

it is considered to be a variant of Henoch Schonlein purpura with only

skin involvement(4). There are few case reports from India as well(5,6).

The etiology of AHEI is not very clear. Poyrazoglu, et al.(7).

reported that 6 of 8 patients had history of recent infection, drug

administration or immunization.

Common differential diagnosis of AHEI include Henoch

Schonlein purpura, meningococcemia, erythema multiforme, urticaria with

hemorrhagic elements and drug eruptions. All these entities are not

difficult to differentiate from AHEI clinically. Spontaneous recovery

usually occurs within 1-3 weeks, without sequelae. Recurrent episodes may

occur. On follow up at one year, our patient did not have any recurrence.

Contributors: KM, RK, MR and SK were involved in

management of the patient. RK and MR reviewed the literature and prepared

the manuscript.

Funding: None.

Competing Interest: None stated.

References

1. Suehiro RM, Soares BS, Eisencraft AP, Campos LM,

Silva CA. Acute hemorrhagic edema of childhood. Turk J Pediatr 2007; 49:

189-192.

2. Morrison RR, Saulsbury FT. Acute hemorrhagic edema

of infancy associated with pneumococcal bacteremia. Pediatr Infect Dis J

1999; 18: 832-833.

3. Krause I, Lazarov A, Rachmel A, Grunwald MM, Metzker

A, Garty BZ, et al. Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy, a benign

variant of leucocytoclastic vasculitis. Acta Pediatr 1996; 85:114-117.

4. Dubin BA, Bronson DM, Eug AM. Acute hemorrhagic

edema of childhood: an unusual variant of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. J

Am Acad Dermatol 1990; 23: 347-350.

5. Shah D, Goraya JS, Poddar B, Parmar VR. Acute

infantile hemorrhagic edema and Henoch Schonlein purpura overlap in a

child. Pediatr Dermatol 2002; 19: 92-93.

6. Kaur S, Thami GP. Urticarial vasculitis in infancy.

Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2003; 69: 223-224.

7. Poyrazoglu H M, Per H, Gunduz Z, Du sunsel R, Arslan D, Narin N,

et al. Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy. Pediatr Int 2003; 45:

697-700.