H

eadache is common in

children and

adolescents. About 60% of children

worldwide report at least 3 attacks of

headache per year [1]. Tension-type headache (TTH) and migraine

are the most common headache disorders in schoolchildren with a

prevalence of 8 and 23%, respectively [2,3]. Despite the high

prevalence of headache in children, it continues to be

under-diagnosed and undertreated. Many children are managed at

home with over-the-counter medications, some children are

managed at primary care and only a small proportion of children,

with difficult to treat headache disorders, are referred and

managed at specialist pediatric services.

Migraine and, to a lesser degree, TTH are

well-studied and described in the pediatric literature, but

little is written on many others, especially rare primary

headache disorders and the uncommon variants and complications

of common headache disorders in children and adolescents. Except

for migraine, the three editions of the International

Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-1, ICHD-2 and

ICHD-3), provided definitions and criteria for the diagnosis of

all headache disorders derived from studies on and experience in

adult patients [4-6]. It is conceivable that the clinical

presentations of most, if not all, primary headache disorders in

children can be different than those in adults [7]. The

differences can be due to the inherent nature of the disease

itself, neurodevelopmental factors, biopsychosocial influences

of the disease, life-style and education, and also children’s

response to pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic therapies.

Therefore, studies on uncommon headache disorders in children

and adolescents are badly needed in order to better define the

conditions and inform management decisions.

CLASSIFICATION

Headache disorders are classified on the

basis of etiology into primary (no other underlying cause),

secondary (when headache is a manifestation of another disorder)

and undetermined etiology (Box I). Headaches are also

sub-classified on the basis of frequency of attacks and duration

of the headache disorder into episodic (less than 15 days per

month) or chronic (attacks occur on at least 15 days per month

over at least three consecutive months). Migraine is further

sub-classified according to clinical features (different types

of migraine) and trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias (TACs) are

sub-classified on the basis of attack duration.

|

Box I Classification of Most Common

Headache Disorders in Children

Primary headaches

• Migraine

• Tension-type headache

• Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias

• Others

Secondary headache

• Medication overuse headache

• Posttraumatic headache

• Brain tumors

• Idiopathic intracranial

hypertension

Others

• Cranial neuropathies

• Facial neuropathies

• Others

|

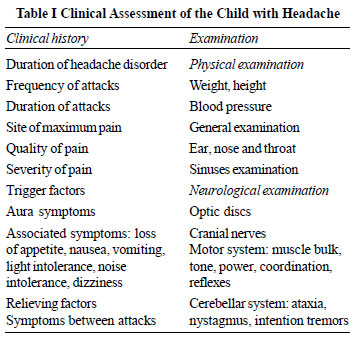

ASSESSMENT OF THE CHILD WITH HEADACHE

In the absence of diagnostic tests and

biomarkers, the diagnoses of primary headache disorders are

based on the clinical features and globally acceptable

definitions and diagnostic criteria. A focused and detailed

clinical history is essential in assessment of children with

headache in order to make a positive diagnosis, and appropriate

classification. Making the right diagnosis allows explaining the

condition to the child and the family, making a rational

decision on investigations if needed, offering the most

appropriate treatment options and helps in predicting prognosis.

Essential elements of clinical history, general examination and

neurological exami-nation are summarized in Table I and

management workup may follow the steps as shown in Fig. 1.

|

| |

| |

| |

|

The severity of pain is best assessed by its

effects on behavior and activities; severe headache stops all

activities during attacks, moderate headache stops some but not

all activities, and mild headache dose not interfere with normal

daily activities. Absence of symptoms between attacks and

complete return to normal self is an important feature of

primary headache. Secondary headaches should be suspected and

considered if red flags are detected on the clinical history,

and physical and neurological examinations (Box II).

|

Box II Red Flags and Indications for

Investigations

Clinical history

Side locked headache

Acute progressive headache

Vomiting on waking up

Deteriorating vision

Seizures

Personality change

Persisting symptoms between attacks

Physical examination

Hypertension

Faltering growth

Delayed puberty

Neurological examination

Papilledema

New neurological deficit

Ataxia

Nystagmus

New squint

|

The diagnosis of common primary headache

disorders such as migraine and tension-type headache can be made

confidently on clinical history, normal examination, absent red

flags and on the application of the ICHD-3 criteria. Other less

common headache disorders may cause difficulties in diagnosis

and management and will be the subject for this review.

GENERAL MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES

Exploring and addressing the concerns of

patients and their families are the first important steps in

successful management. Advice on healthy life style – regular

meals, sleep, exercise and rest may reduce impact and improve

coping with headache.

For acute treatment, simple analgesics should

be used in appropriate dosages and as early as possible after

onset of headache. Children should avoid taking painkillers on

more than three days per week in order to avoid medication

overuse headache (MOH). Triptans can also be given in acute

migraine attacks in accordance with local license and

regulations and with similar precautions to avoid MOH.

Evidence-based recommendation in the

prevention of migraine can be hard to find with conflicting

evidence, however treatment with propranolol, topiramate,

flunarizine and amitriptyline can be considered on individual

basis. Specific treatment for rare headache disorders will be

discussed separately.

CHRONIC MIGRAINE

Migraine is a common disorder with a

prevalence of around 10% in schoolchildren [1], and chronic

migraine (CM) is a subtype of migraine. The diagnosis of CM is

made when headache occurs on at least 15 days per month on at

least 3 consecutive months, of which at least on 8 days per

month the headaches are those of migraine [6].

Migraine may present as CM from the onset,

but it can also evolve over a period of time in children with

episodic migraine. It is estimated that about 2% of adolescents

suffer from CM and at least half the patients overuse

medication; simple analgesics or anti-migraine drugs such as

sumatriptan [8]. CM is more common in girls than boys and more

prevalent in adolescents than in younger children. CM has a

significant impact on the child’s quality of life, school

attendance and educational attainment as compared to children

with episodic migraine and control healthy children [8].

Management

The management of children with CM can be

difficult and, ideally, needs a multidisciplinary approach and a

positive contribution from parents and guardians, clinical

psycho-logy services, education and school teachers and also

from school nurses. Investigations are not necessary except in

presence of red flags or new abnormalities on neurological

examination. An individual migraine management plan agreed upon

by the child, the parents and members of the multi-disciplinary

team (MDT) promotes better manage-ment of headache at home and

at school and may reduce impact on education and quality of

life.

Medical management starts with reducing the

risk of medication overuse and treatment of MOH when present.

Pain killers should, therefore be avoided as they have a limited

role. Preventive drugs aim to reduce the frequency and the

severity of migraine attacks and to improve the quality of life.

Several medications are used but with sometime, a conflicting

evidence for their effectiveness. Amitriptyline, with and

without cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), topiramate,

flunarizine and botox are commonly offered to patients [9-11].

Greater occipital nerve block and botox injections are possible

future management options. Calcitonin-gene related peptide

(CGRP) monoclonal antibodies are shown to be successful in

migraine prevention in adults, but still awaiting trials and

licensing in children.

Prognosis: The prognosis and the

long-term course of CM have not been well studied in children,

but the impact on quality of life is a consistent feature and

studies showed reduced educational attainment and earning power

during adult life [12].

HEMIPLEGIC MIGRAINE

Hemiplegic migraine (HM) is a form of

migraine with motor aura and depending on presence or absence of

other affected family members; it is divided into familial

hemiplegic migraine (FHM) or sporadic hemiplegic migraine (SHM).

FHM is sub-classified according to the underlying genetic

mutation; FHM1 is associated with a mutation on the CACNA1A

gene, FHM2 on the ATP1A2 gene, FHM3 on SCN1A and

FHM (other loci) when no genetic mutation can be found despite

the familial occurrence of the disease.

The prevalence of HM is not known, but is

considered rare. About 2% of patient seen at a specialist

children headache clinic have HM [13]. Girls are more commonly

affected than boys and its peak incidence is during adolescence.

The clinical presentation of HM can be

distressing to the child, frightening to the family and can pose

a dilemma in diagnosis for clinicians. Attacks can be triggered

by minor head trauma and followed by complex aura; a combination

of visual, sensory, speech and motor symptoms. The headache that

follows can be severe and is often associated with intense

nausea and vomiting that may lead to confusion and dehydration.

A recent study on a cohort of 46 children

with HM showed that children present with fewer non-motor auras

than adults and the first attack may be preceded by transient

neurological signs and symptoms especially in early childhood

[14]. The attacks can last over 1-2 days and children will be,

invariably, investigated with neuroimaging to rule out space

occupying lesions, intracranial bleeding or arterial ischemic

strokes. Investigation will always be necessary, especially on

the first presentation as the diagnosis, as defined by (ICHD-3),

can only be made after at least two fully reversible attacks.

Distinguishing HM from stroke can be

difficult on clinical features alone as they share many

symptoms. Standard MRI of the brain may not be helpful and

specialist cerebral perfusion studies using functional MRI and

arterial spin labeling (ASL), only available at limited centers,

may demonstrate areas of cerebral hypoperfusion soon after onset

of symptoms and hyperperfusion 12-14 hours after onset. The

changes in perfusion are not limited to the territories of the

main cerebral arteries but they are evident across the

boundaries suggesting neural rather than vascular basis of this

phenomenon [15,16].

Management

Treatment of acute attacks once the diagnosis

is established should aim at reassuring the child and parents,

providing effective pain relief, hydration and monitoring of

symptoms. Simple analgesics (paracetamol 10-20 mg/kg or

ibuprofen 7.5-10 mg/kg) are the preferred options. The use of

triptans is currently not recommended as all clinical trials

excluded children and adults with HM and there is no evidence of

their safety in children and adolescents. The exclusion from

trials was based on the theoretical risk of triptans

exacerbating cerebral vasoconstriction and causing cerebral

infarction.

Care should be taken to prevent dehydration

by encouraging oral fluids, but intravenous fluids may be

necessary. Antiemetic medications such as metoclopra-mide or

ondansetron may also be needed.

Preventative treatment may be necessary if

attacks are prolonged, frequent or causes distress to child and

parents. Topiramate, amitriptyline and flunarizine in particular

are good treatment options.

Prognosis: Counseling of patients should

take into account the known natural history of the disease,

which is characterized by periods of remissions and relapses.

The attacks of HM tend to be frequent and severe during

adolescence and also in late adult life with periods of

remission in between. A follow up of eight family members for a

mean period of ten years showed the disease to be clinically

stable [17]. Children with FHM1 due to associated CACNA1A

gene mutation have an increased risk of progressive ataxia in

late adult life and children with FHM3 due to SCN1A

mutation are at a higher risk for epilepsy.

THUNDERCLAP HEADACHE

Thunderclap headache (TH) is a term given to

describe sudden severe headache that reaches its peak intensity

within seconds or minutes and persists for hours. TH may become

recurrent over several weeks if untreated. TH is a secondary

headache in most cases and a diagnosis of primary TH should only

be made after full, appropriate and timely investigations

including neuroimaging. The prevalence of TH in children and

adolescents is not known and it is rare in pediatric clinical

practice. Cases reported in children are mostly secondary to

sinus venous thrombosis [18].

The clinical features of TH in children are

probably similar to those in adults. The clinical picture is

usually dominated by the abrupt onset of the headache and its

severe intensity described by patients as the most severe

headache they have ever experienced, prompting them to seek

urgent medical advice and assessment. The headache attacks can

be brief, but repetitive. Although the criteria for the

diagnosis of TH in ICHD-3 (Box III) are that of primary

TH, it is always necessary to exclude underlying intracranial

vascular disease.

|

Box III Criteria for Diagnosis

of Thunderclap Headache

A. Severe head pain fulfilling

criteria B and C

B. Abrupt onset reaching maximum

intensity in <1 min

C. Lasting for

³5

min

D. Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3

diagnosis.

|

| |

Secondary TH: TH may be the

presenting symptoms in patients with several intracranial

vascular disorders. The most common causes of TH in children and

adolescents are intracerebral haemorrhage, cerebral venous

thrombosis, subarachnoid haemorrhage with or without ruptured

arterial aneurysms and reversible cerebral vasoconstriction

syndrome (RCVS). Secondary TH may not be

immediately distinguishable from primary TH and therefore full

neurological examination and measurement of arterial blood

pressure are mandatory. Prompt recognition and urgent

appropriate assessment start at emergency department in order to

avoid life-threatening complications [19].

Management

Investigations at presentation should include

brain MRI and MR angiography. Other investigations should also

include CSF opening pressure, CSF microscopy, culture, protein

and glucose (paired with blood glucose) and examination for

xanthchromia at appropriate time interval from presentation. MRA

may need to be repeated if RCVS is highly suspected, as

vasoconstriction may not be apparent in the early stages of the

disease.

Treatment aims to relieve symptom while

addressing the management requirements of the underlying

condition.

CHIARI MALFORMATIONS HEADACHE

Chiari malformation is a congenital anomaly

of the posterior cranial fossa characterized by crowding of its

contents, a caudal displacement of the cerebellar tonsils and

brainstem through the foramen magnum and an associated expansion

of the CSF spaces in the cervical and possibly the thoracic

spinal canal creating a static or progressive syrinx. Chiari

malformation is classified into types 1-4 depending on the

degree of malformation, the extent of cerebellar and brainstem

herniation into the foramen magnum, cerebellar hypoplasia,

syringomyelia, obstruction of CSF flow and presence of an

encephalocele.

Chiari malformation type 1 (CM1) is the most

common form and it is asymptomatic in the vast majority of

cases. In CM1, there is mild to moderate crowding of the

posterior fossa and a descent of cerebellar tonsils between 5-10

mm below the foramen magnum with no or a very small syrinx. It

is commonly reported as an incidental finding in about 1% of

children and young people undergoing brain and spine MRI [20].

Headache due to CM1 is described in the

ICHD-3 as brief episodes lasting less than 5 minutes of

occipital or suboccipital pain, precipitated by cough or

Valsalva maneuver and it remits after successful treatment of

CM1 [6]. It is important to keep in mind that children with CM1

may also complain of other types of headache such as migraine

and tension-type headache, and they should not be confused with

CM1 headache. On rare occasions, children with CM1 may present

with other symptoms related to brainstem or cerebellar

dysfunction including visual disturbances, dysphonia, dysphagia,

sleep apnea, incoordination and sensory disturbances.

The diagnosis of CM1 is usually made on the

sagittal MRI of the brain and the cervical spine. The management

of children with CM1 is non-surgical in most patients after

discussion with a neurosurgeon and a neuroradiologist. Medical

management should include appropriate manage- ment of the pain

symptoms and a follow up imaging over a period of time to

confirm the non-progressive nature of the malformation and the

size of the syrinx, if present, in particular [21].

Surgery is only recommended for patients with

features suggesting brainstem or cerebellar compression, a large

or progressive syringomyelia or with a poorly controlled,

typical CM1 headache disorder. A single center experience in the

surgical treatment of children with CM1 over 25 years showed

that children with typical CM1 headache who were treated with

foramen magnum decompression (FMD) plus duraplasty achieved a

greater improvement in their headache than those treated with

FMD alone [22].

PRIMARY STABBING HEADACHE

Primary stabbing headache (PSH) is an

uncommon syndrome, also called ice-pick headache, characterized

by very short attacks. While ICHD-2 states that pain is confined

exclusively to the trigeminal territory, it has been accepted in

ICHD-3 to cross beyond the boundaries of the trigeminal nerve

and can be unilateral or bilateral in location (Box IV).

The typical stab lasts a few seconds; however, attacks lasting

up to 15 minutes in children and adolescents have been reported

[23].

|

Box IV Criteria for the Diagnosis of

Primary Stabbing Headache

A. Head pain occurring spontaneously

as a single stab or series of stabs and fulfilling

criteria B and C

B. Each stab lasts for up to a few

seconds

C. Stabs recur with irregular

frequency, from one to many per day

D. No cranial autonomic symptoms

E. Not better accounted for by

another ICHD-3 diagnosis.

|

Although the exact prevalence of PHS in the

pediatric population is unknown, 4-5% of children referred to

headache centers have PSH [23-25]. In an Italian study, 12.4% of

children with headache younger than 6 years had PSH [26]. Girls

and boys are equally affected, though in adults PSH is more

common in females [27]. Other primary headaches; migraine and

TTH may coexist with PSH in children [28-30]. Associated

symptoms, such as photo-phobia, phonophobia, nausea, and

dizziness, have been described in 20-50% of patients. Absence of

autonomic symptoms is the main feature that differentiates PSH

from trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias.

The pathophysiology of PSH is unknown, but

spontaneous firing of trigeminal fibers or abnormalities of the

descending pain control have been suggested as possible

mechanisms [27]. The relatively higher prevalence of PSH in

younger children suggests that PHS may be a precursor of

migraine/TTH [16].

Treatment of PSH in children is often not

necessary, unless the stabs are very frequent and interfere with

normal activities. Evidence for any medications in the treatment

of PSH is lacking, but indomethacin may offer an excellent

relief of pain when given in a dose of 25 mg three times per day

for 6-8 weeks alongside omeprazole for gastric protection.

Melatonin, amitriptyline, propanol, and COX2-inhibitors were

effective in adults and may be used in children [27].

TRIGEMINAL AUTONOMIC CEPHALALGIAS

Trigeminal Autonomic Cephalalgias (TACs) are

also uncommon, especially in pediatric age. However, they must

be considered even in young children, in order to offer the

appropriate treatment. They include cluster headache (CH),

Paroxysmal hemicrania (PH), Hemicrania Continua (HC), and

Short-lasting Unilateral Neuralgiform headache attacks with

Conjunctival injection and Tearing (SUNCT) or with cranial

autonomic symptoms (SUNA). Table II presents the

characteristics and the differential diagnosis of these

conditions.

Cluster Headache

The prevalence of cluster headache (CH) in

the pediatric population is around 0.1% [31]. CH is

characterized by severe and sometimes excruciating unilateral

pain, mainly in the orbital, supraorbital, and/or temporal

region, lasting 15-180 minutes and recurring up to 8 attacks per

day. Attacks are often associated with restlessness and/or

ipsilateral autonomic symptoms, such as conjunctival injection,

lacrimation, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, eyelid edema,

forehead and facial sweating, miosis, and ptosis. The usual

presentation of CH is that of recurrent bouts of headache, each

bout consisting of several distinct headache attacks. In

episodic CH, the bouts of headache last from 7 days to 1 year,

and are separated by headache-free periods without treatment of

at least 3 months. In chronic CH, the headache-free period

between bouts is shorter than 3 months. It has been recently

suggested that the attacks can be shorter and less frequent in

children than in adults and restlessness can be more difficult

to demonstrate [7,32].

CH is more common in children over 10 years

of age, but it has been reported in children younger than 6

years of age [33,34]. Complex genetic factors are probably

involved in CH etiology [35,36]. However, it was noted that

there is a low prevalence (9%) of CH in the relatives of young

patients [34]. Environmental factors such as high exposure to

second hand smoking has been suggested as a risk factor for CH

development [34,37].

Treatment: Treatment of acute attacks in

children and adolescents consists of administering, as early as

possible after onset, either sumatriptan 10 mg or zolmitriptan 5

mg (as nasal spray), which are the only licensed triptans for

adolescents 12-18 years of age in Europe as well as high flow

100% oxygen at 12-15 L/min with a rebreathing mask [38].

For the prevention of CH, verapamil is the

drug of first-choice in adults. It has been used at the dose of

3-10 mg/kg/d in children and adolescents [38]. However,

verapamil can be difficult to manage in pediatric age because of

its side effects (effect on length of the PR interval and the

negative inotropic effect). Alternative treatments are melatonin

(0.1-0.2 mg/kg/d) and topiramate (1-2 mg/kg/d). A short course

of steroids like prednisone 2 mg/kg/day is reported to stop the

cluster within 5 days [34].

Greater occipital nerve block was shown to be

effective in three children [39].

Paroxysmal Hemicrania

Paroxysmal hemicrania (PH) is characterized

by short lasting (2-30 min), multiple and unilateral pain

attacks, with a typical attack frequency of more than 5 per day.

Pain is commonly associated with ipsilateral cranial autonomic

symptoms. PH is defined as episodic when attacks last from 7

days to 1 year and are separated by time intervals longer than 3

months. In chronic PH, the attack has to last more than 1 year

without interruption or with pain-free intervals shorter than 3

months. In children, PH can be atypical with bilateral pain,

attack duration longer than 30 minutes and attack frequency less

than 5 per day making it difficult to differentiate from CH

[7,40,41].

PH responds well to treatment with

indomethacin, making it a good therapeutic first line option in

all patients with unilateral short-lasting pain, associated with

cranial autonomic symptoms.

Hemicrania Continua

Hemicrania continua (HC) is characterized by

continuous unilateral headache with exacerbations of moderate or

greater intensity for at least 3 consecutive months. As in PH,

cranial autonomic symptoms ipsilateral to pain and/or sense of

restlessness are needed for the diagnosis. The response to

indomethacin should be complete, but can be variable in some

children. Only a few pediatric cases of HC have been published

with one patient responding to treatment with Botulinum toxin A

[42,43].

SUNCT and SUNA

These short-lasting neuralgiform attacks,

lasting from 1 to 600 sec, involve the trigeminal territory

unilaterally. The attacks can be isolated or can recur in

series. Pain is associated with conjunctival injection and/or

tearing in SUNCT or other cranial autonomic symptoms, such as

nasal congestion and/or rhinorrhea, eyelid edema, forehead and

facial sweating, miosis, and/or ptosis in SUNA. Only four cases

of pediatric SUNCT (3 idiopathic and 1 symptomatic) have been

described thus far [7].

CONCLUSIONS

Pediatricians are familiar with the diagnosis

and treatment of common headache disorders in children and

adolescents. Awareness of the different types of atypical or

rare headache disorders allows better assessment and a more

successful management. Learning points related to these

disorders are detailed in Box V.

|

Box V Learning Points for

Uncommon Pediatric Headache Disorders

Chronic migraine

• Affects 1-2% of adolescents

• Management requires

multidisciplinary approach in most patients and

realistic targets

• Management aims to revert

chromic migraine to episodic migraine

• Emphasis on life style factors

and preventive treatment· Avoid medication overuse

and address it if present

Hemiplegic migraine

• Diagnosis of HM can only be

made after at least 2 fully reversible episodes

• Investigations and neuroimaging

will be necessary at first presentation

• Triptans are not recommended

for treatment of acute attacks

• Flunarizine may be a good

option for the prevention of HM

Thunderclap headache

• TH presents with sudden onset

severe headache that reaches its peak within minutes

• Always exclude underlying

intracranial cause by appropriate investigations

Chiari malformation 1

• CM1 can be asymptomatic

incidental finding in about 1% of people

• Headaches due to CM1 are short,

occipital and triggered by Valsalva maneuver.

Discuss with a neurologist, a neurosurgeon and a

pediatric neuro-radiologist

• Surgical treatment only

required in a small proportion of patients

Primary stabbing headache

• Headache due to PSH are very

brief and repetitive

• No associated autonomic

features

• Excellent response to

indomethacin can be expected

Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias

• Duration of attacks are

important in diagnosis, but acknowledge some overlap

• At least one autonomic feature

is present

• Agitation and distress are

important features

• PH and HC respond to

indomethacin in many patients

• Nasal sumatriptan and high flow oxygen are

effective acute treatment for CH.

|

Diagnosis should be based on the recognized

clinical criteria of the ICHD. Investigations to exclude serious

underlying neurological disorders may be necessary, but should

be interpreted with caution, in order to avoid over-diagnosis of

incidental findings such as Chiari malformation 1. Chronic

migraine can be associated with adverse impact on quality of

life and can be difficult to manage. Hemiplegic migraine may

pose diagnostic difficulties making investigations necessary

including MR angiography, especially at first presentation.

Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias and stabbing headache are

relatively rare in children, but with the correct use of

diagnostic criteria, management plans with appropriate treatment

options and realistic expectations, it is possible to address

the patient needs.

Contributors: All authors

contributed equally and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: None; Competing interest:

None stated.

REFERENCES

1. Abu-Arafeh I, Russell G. Prevalence of

headache and migraine in schoolchildren. Brit Med J.

1994;309:765-9.

2. Abu-Arafeh I, Razak S, Sivaraman B,

Graham C. The prevalence of headache and migraine in

children and adolescents: A systematic review of

population-based studies. Dev Med Child

Neurol. 2010;52:1088-97.

3. Laurell K, Larsson B, Eeg-Olofsson O.

Prevalence of headache in Swedish schoolchildren, with a

focus on tension-type headache. Cephalalgia, 2004;24:380-8.

4. Headache Classification Committee of

the International Headache Society. Classification and

Diagnostic Criteria for Headache Disorders, Cranial

Neuralgias and Facial Pain. Cephalalgia. 1988;8:1-96.

5. Headache Classification Committee of

the International Headache Society (IHS). The International

Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd edition.

Cephalalgia. 2004;38:1-211.

6. Headache Classification Committee of

the International Headache Society (IHS). The International

Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition.

Cephalalgia. 2018;24:1-152.

7. Ozge A, Faedda N, Abu-Arafeh I, et al.

Experts’ opinion about the primary headache diagnostic

criteria of the ICHD-3rd edition beta in children and

adolescents. J Headache Pain, 2017;18:11.

8. Lipton RB, Manack A, Ricci JA, et al.

Prevalence and burden of chronic migraine in adolescents:

Results of the chronic daily headache in adolescents study

(C-dAS), headache, 2011;51:693-706.

9. Powers SW, Coffey CS, Chamberlin LA,

et al. Trial of amitriptyline, topiramate, and placebo for

pediatric migraine. NEJM. 2017;376:115-24.

10. Power SW, Kashikar-Zuck SM, Allen JR,

et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy plus amitriptyline for

chronic migraine in children and adolescents: A Randomized

Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2013;310:2622-30.

11. Le K, Yu D, Wang J, et al. Is

topiramate effective for migraine prevention in patients

less than 18 years of age? A meta-analysis of randomised

controlled trials. J Headache Pain. 2017;18:4-10.

12. Adams AM, Serrano D, Buse DC, et al.

The impact of chronic migraine: The chronic migraine

epidemiology and outcomes (CaMEO) study methods and baseline

results. Cephalalgia. 2015;35:563-78.

13. Abu-Arafeh I, MacLeod S. Serious

neurological disorders in children with chronic headache.

Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:937-40.

14. Toldo I, Brunello F, Morao V, et al.

First attack and clinical presentation of hemiplegic

migraine in pediatric age: A multicenter retrospective study

and literature review. Front Neurol.

2019;10:1079.

15. Boulouis G, Shotar E, Dangouloff-Ros

V, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging arterial-spin-labeling

perfusion alterations in childhood migraine with atypical

aura: a case–control study. Dev Med Child Neurol.

2016;58:965-9.

16. Cadiot D, Longuet R, Bruneau B, et

al. Magnetic resonance imaging in children presenting

migraine with aura: Association of hypoperfusion detected by

arterial spin labelling and vasospasm on MR angiography

findings. Cephalalgia. 2018;38:949-58.

17. Indelicato E, Nachbauer W, Eigentler

A, et al. Ten years of follow-up in a large family with

familial hemiplegic migraine type 1: Clinical course and

implications for treatment. Cephalalgia. 2018;38:1167-76.

18. Gosh PS, Rothner AD, Zakha KG,

Friedman NR. Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome:

A rare entity in children presenting with thunderclap

headache. J Child Neurol. 2011; 26:1580-4.

19. Raucci U, Vecchia ND, Ossella C, et

al. Management of childhood headache in the emergency

department: review of the literature. Front Neurol.

2019;10:886.

20. Aitkin LA, Lindan CE, Sidney S, et

al. Chiari type I malformation in a pediatric population.

Pediatr Neurol, 2009;40:449-54

21. Abu-Arafeh I, Campbell E. Headache,

Chiari malformation type 1 and treatment options, Arch Dis

Child 2017;102:210-1.

22. Raza-Knight S, Mankad K, Prabhakar P,

et al. Headache outcomes in children undergoing foramen

magnum decompression for Chiari I malformation. Arch Dis

Child. 2017;102:238-43.

23. Fusco C, Pisani F, Faienza C.

Idiopathic stabbing headache: Clinical characteristics of

children and adolescents. Brain Dev. 2003;25:237-40.

24. Kramer U, Nevo Y, Neufeld MY, et al.

The value of EEG in children with chronic headaches. Brain

Dev, 1994;16:304-8.

25. Vieira JP, Salgueiro AB, Alfaro M.

Short-lasting headaches in children. Cephalalgia.

2006;26:1220-4.

26. Raieli V, Eliseo M, Pandolfi E, et

al. Recurrent and chronic headaches in children below 6

years of age. J Headache Pain. 2005;6:135-42.

27. Hagler S, Ballaban-Gil K, Robbins MS.

Primary stabbing headache in adults and pediatrics: A

review. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2014;18:450

28. Soriani S, Battistella PA, Arnaldi C,

et al. Juvenile idiopathic stabbing headache. Headache.

1996;36:565-7.

29. Abu-Arafeh I. Primary stabbing

headache: The need for a definition for children and

adolescents. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2020;62:10.

30. Ahmed M, Canlas J, Mahenthiran M, Al-Ani

S. Primary stabbing headache in children and adolescents.

Dev Med Child Neurol. 2020;62:69-74.

31. Ekbom K, Ahlborg B, Schéle R.

Prevalence of migraine and cluster headache in Swedish men

of 18. Headache 1978;18:9-19.

32. McAbee GN. A review of episodic and

chronic pediatric headaches of brief duration. Pediatr

Neurol. 2015;52:137-42.

33. Majumdar A, Ahmed MA, Benton S.

Cluster headache in children - experience from a specialist

headache clinic. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2009;13:524-9.

34. Mariani R, Capuano A, Torriero R, et

al. Cluster headache in childhood: case series from a

pediatric headache center. J Child Neurol. 2014;29:62-5.

35. Schurks M. Genetics of cluster

headache. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2010;14:132-9.

36. Sjostrand C, Russell MB, Ekbom K, et

al. Familial cluster headache: Demographic patterns in

affected and nonaffected. Headache. 2010;50:374-82.

37. Rozen TD. Childhood exposure to

second-hand tobacco smoke and the development of cluster

headache. Headache. 2005;45:393-4.

38. Mack KJ, Goadsby P. Trigeminal

autonomic cephalalgias in children and adolescents: Cluster

headache and related conditions. Semin Pediatr Neurol.

2016;23:23-6.

39. Puledda F, Goadsby PJ, Prabhakar P.

Treatment of disabling headache with greater occipital nerve

injections in a large population of childhood and adolescent

patients: A service evaluation. J Headache Pain. 2018;19:5.

40. Tarantino S, Vollono C, Capuano A, et

al. Chronic paroxysmal hemicrania in paediatric age: Report

of two cases. J Headache Pain. 2011;12:263-7.

41. Raieli V, Cicala V, Vanadia F.

Pediatric paroxysmal hemicrania: A case report and some

clinical considerations. Neurol Sci. 2015;36:2295-6.

42. Fragoso YD, Machado PC. Hemicrania

continua with onset at an early age. Headache.

1998;38:792-3.

43. Prasad M, Ramdas S, Abu-Arafeh I. A child with hemicrania

continua phenotype responsive to Botulinum toxin-A. J Pediatr

Neurol. 2012;10:155-9.