|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2021;58:639-642 |

|

Developmentally

Supportive Positioning Policy for Preterm Low Birth Weight

Infants in a Tertiary Care Neonatal Unit: A Quality Improvement

Initiative

|

|

Jaya Upadhyay, Poonam Singh, Kanhu Charan Digal, Shantanu Shubham,

Rajat Grover, Sriparna Basu

From Department of Neonatology, All India Institute of Medical

Sciences, Rishikesh, Uttarakhand.

Correspondence to: Prof Sriparna Basu, Department of Neonatology, All

India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh, Uttarakhand 249203.

[email protected]

Received: January 06, 2020;

Initial review: April 07, 2020;

Accepted: September 26, 2020.

Published online: January 2, 2021;

PII:S097475591600269

|

Objective: To improve developmentally supportive

positioning practices by 50% in neonates weighing <1800 g, admitted in a

neonatal intensive care unit over 6 months. Methods: Infant

Position Assessment Tool (IPAT) scores were used for assessment of the

ideal position. Proportion of neonates with IPAT score

³8 and

improvement of average IPAT score were the process and the outcome

measures, respectively. At baseline, 16.6% of infants had optimum

position. After root cause analysis, interventions were done in multiple

Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles of educational sessions, positioning

audits, use of low-cost nesting aids, and training of mothers.

Results: Over 21 weeks, 74 neonates were observed at 714

opportunities. Over 6 months, mean (SD) IPAT score improved from 3.4

(1.4) to 9.2 (2.8). Optimum positioning was maintained in 83.3% neonates

during sustenance phase. Conclusions: Low-cost interventions,

awareness regarding standards of optimum positioning and involvement of

primary caregiver can effectively improve infant positioning practices.

Keywords: Conformational position, Infant Positioning

Assessment Tool (IPAT), Nursing care, Posture, Outcome.

|

|

I n developmental

supportive care (DSC), positioning is the most important

strategy that affects physiological stability and reduces stress

[1]. Optimum positioning improves sleep, reduces pain, decreases

apnea/desaturation episodes, improves ther-mal regulation, skin

integrity and neurobehavioral organization [2,3]. Several

studies have documented beneficial effects of supportive

positioning interventions including reduction in musculoskeletal

abnormalities and better neuromotor outcomes [4,5]. Frequent

position changes with the use of ‘nesting’ or ‘conformational

positioner’ have shown to improve the postural regulation with

maintenance of optimum position [6,7].

The awareness of neonatal caregivers

regarding infant positioning is scanty [8]. Improvement of

practices were documented after educational training,

positioning audits and policy formation [9]. This quality

improvement (QI) initiative was undertaken to improve the

develop-mentally supportive positioning practices in low birth

weight neonates.

METHODS

Our neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) is a

24-bedded level-III unit with >2500 deliveries/year and >100

admission/month. The nurse: patient ratio is 1:1 for neonates on

ventilator, 2:1 for sick neonates and 4:1 for relatively stable

infants. The concept of DSC in our unit was limited to the

routine use of a shoulder roll only. On a cross-sectional review

of practice, over 80% admitted neonates at our center were found

in unacceptable positions, supine with retracted

shoulders/extremities (93.4%), undue neck flexion (70%) and

excessive hip abduction due to oversized diaper (100%).

We aimed to improve developmentally

supportive positioning practices by 50% in neonates weighing

<1800 g admitted in the NICU over 6 months (April,

2019-September, 2019). This QI initiative was based on

point-of-care quality initiative (POCQI) model [10]. Ethical

clearance was obtained from Institute Ethics Committee.

Infant positioning assessment tool (IPAT;

Philips Children’s Medical Ventures), validated by several

studies [11-14] was used to improve the positioning practices.

Eligible neonates (birthweight <1800 g) were scored by a team of

‘Positioning proponents (PP)’, once in every shift and an

average daily score was assigned to each baby. Proportion of

neonates with average IPAT score

³8 was taken

as the process measure. Improvement in mean IPAT scores was the

outcome measure.

Baseline phase (4 weeks): In this phase,

the applicability of IPAT score was validated in 6 neonates at

30 oppor-tunities. A team of two doctors and six nurses

identified as PP, were trained in developmentally supportive

position-ing practices and IPAT scoring. Mean (SD) IPAT score

was 3.4 (1.4) and proportion of neonates with mean IPAT

³8 was 16.6%.

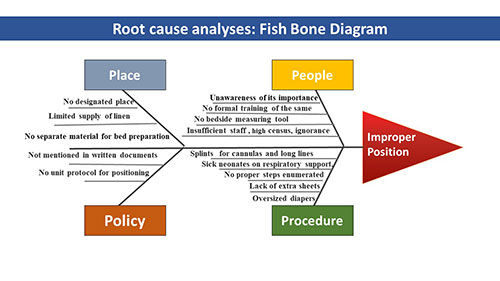

Potential causes of improper positioning identified through root

cause analysis (Fig. 1) included lack of

knowledge/skills, unavailability of positioning aids, high

patient load, respiratory support, multiple infusions and

non-availability of measurement tool.

|

|

Fig. 1 Root cause analyses: Fish

bone diagram for improper positioning.

|

Intervention phase: After baseline phase,

Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles (Web Fig. 1) were

used for interventions. IPAT was introduced and one-to-one

teaching, hands-on demonstration-cum-practice session and

assessment of nurses and residents were started. Data were

recorded in excel sheet and plotted on run chart weekly. To

prevent bias, average score was disclosed weekly.

PDSA-1: Learning by doing (4

weeks): A schedule and the teaching material were

distributed among team members. IPAT print-outs were made

available at the bedside. Group teaching, informal bedside and

one-to-one teaching, position demonstration on mannequin and

baby were continued for next 2 weeks in every nursing shift.

Nurses were assessed once weekly for IPAT scoring of five

neonates with demonstration of ideal positioning. Additional

review sessions were organized for newly-posted residents and

nurses. Educational material was shared electronically. Finally,

IPAT scoring was made a part of daily nursing care with scoring

done in each shift and entered in nursing notes.

PDSA-2: Customized boundary (4

weeks): Preparation of boundaries or ‘nesting’ with rolled

linens was detected as one of the limiting factors due to

non-availability of linens and reluctance of nurses for the

labour-intensive process of preparing the nest. To resolve this,

we prepared customized low-cost, washable and autoclavable, foam

based reusable boundaries with covers by the hospital tailor (Fig. 2).

This intervention decreased the require-ment of linen rolls and

significantly reduced the time required for positioning of the

neonates without impos-ing an additional burden to prepare

nesting, boosting their enthusiasm for improving position. After

this intervention, 50% of neonates had an IPAT score

³8.

|

|

Fig. 2 Positioning aid for

optimum positioning.

|

Two sick neonates were observed to developed

occipital bedsore due to prolonged supine positioning. In order

to maintain high IPAT score, nurses were maintaining supine

posture with fixed boundaries without changing to lateral/prone

positions. An amendment in positioning policy was made with

inclusion of compul-sory three-hourly position change.

PDSA-3: Appraisal and improvement

(12 weeks): In this phase, we started selecting ‘PP of the week’

and appreciating them with a badge, which further improved the

zeal of caregivers. Workshops on DSC with weekly refresher

sessions were conducted. Now, positioning be-came a routine

practice amongst the caregivers improving the proportion of

neonates with IPAT ³8

to 72.5%.

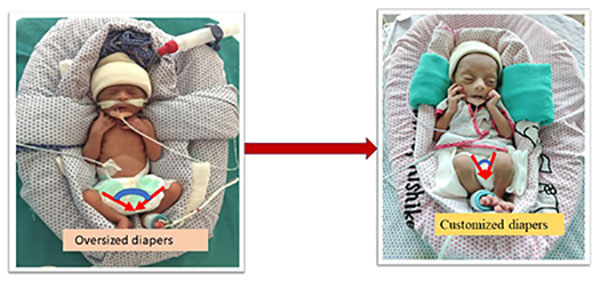

PDSA-4: Sizing the diapers (4

weeks): Following third PDSA cycle, it was analyzed that

position of hips and legs could not be maintained because of

oversized diapers. Since small diapers were not a part of

hospital supply, we started making customized diapers for

preterm with cotton and gauze (Fig. 3). After

this, the number of neonates with oversized diapers reduced from

74.5-20%.

|

|

Fig. 3 Customized diapers for

extremely low birth weight babies.

|

PDSA-5: Training of mothers (8

weeks): After fourth PDSA cycle there was a visible improvement

in position-ing practices of the unit. Team analyzed that most

of the LBW neonates are shifted to step-down units with their

mothers soon after clinical stabilization, and decided to train

the mothers. Teaching materials and posters were prepared in the

local language. Demonstrations were done using mannequins daily

for one week. Every new mother was given a refresher tutorial.

Training mainly focussed on preparation of boundaries using

easily available home-stuff such as towels and scarfs,

preparation of shoulder rolls and its correct placement,

difference between improper and proper positions and their

long-term implications. ‘Position expert’ mothers were praised

and asked to teach other mothers. Considerable acceptance was

noted in their behavior.

RESULTS

Before starting interventions, each PP

independently scored 6 neonates at 30 opportunities. Inter-rater

reliability was analyzed with interclass correlation coefficient

(95% CI) of 0.89 (0.83-0.94) using two-way mixed model,

suggesting a strong level of agreement and high reliability of

data-recording. For the position data, we calculated the

baseline mean using the first 10 data-points and recalculated

the mean whenever a shift in data was identified. In the

baseline phase, 18 neonates with mean (SD) birthweight and

gestational age of 1230 (265) g and 30.5 (2.6) weeks,

respectively were observed over 4 weeks. Mean (SD) IPAT score

was 3.4 (1.4) and 16.6% of eligible neonates had IPAT score

³8.

Throughout this project, 74 neonates were

observed at 714 opportunities. Forty-four nurses, 10 senior

residents, 15 junior residents and 52 mothers were trained in

standard positioning practices. Total 23 teaching sessions were

conducted including 12 sessions of hands-on demons-tration, 2

institutional workshop and 9 assessment sessions. For training

of mothers, 12 teaching sessions and 20

demonstration-cum-hands-on training were conducted.

After first PDSA, mean (SD) IPAT score

improved to 5.2 (1.6) with biggest limitation being lack of

positioning aids. After third and fourth PDSA, introduction of

nesting rolls and appropriate size diapers had significantly

improved mean (SD) IPAT score to 9.2 (2.8) with sustenance for

next 6 weeks. The chart showed less than expected number

of runs signalling for an improved practice. In the last PDSA

cycle, the baseline data was recorded again when the baby was

shifted to step-down unit with the mother. Baseline mean (SD)

IPAT scores of 3.5 (1.3) improved over next 5 weeks to 8.3 (0.2)

(Web Fig. 2).

DISCUSSION

This short-term QI project aimed to improve

the practice of infant positioning. A significant improvement

was noted in the proportion of admitted neonates with IPAT score

³8

from the baseline of 16.6-83.3%. In coherence with other

projects on position improvement [12-14], nursing teaching and

demonstration sessions were found to be most impactful.

Inclusion of mothers in the loop was the most important factor

for sustenance policy.

Compared to previous reports [12-14], the

major difference in this project was the achievement of targeted

improvement within a short time-span. The quick response was

attributed to multiple PDSA cycles, adopting the changes and

policy formation in each step. Advent of customized nesting

boundary was a cost-effective intervention with minimal

consumption of linen. The biggest strength of this project was

involvement of mothers as an addition to the concept of family-centred

care. The major limitation was that we did not assess long-term

developmental outcome.

To conclude, this QI project, using simple

cost-effective interventions through multiple PDSA cycles and

team effort, led to a considerable improvement in positioning

practices of our unit. Involvement of mothers in the project was

an important addition for better sustenance.

Ethics clearance: Institutional ethics

committee, AIIMS, Rishikesh; AIIMS/IEC/19/698; dated

April 12, 2019.

Contributors: JU, PS, SB:

conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated and

supervised data collection, drafted the initial manuscript; KCD,

SS, RG: coordinated and supervised data collection, and reviewed

and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final

manuscript.

Funding: None; Competing

interests: None stated.

| |

|

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS?

•

Compliance with

developmental supportive positioning can be improved by

standardizing positioning policy, staff education, low

cost interventions to ease the process of positioning,

and involvement of primary care giver to ensure long

term benefits.

|

REFERENCES

1. Blackburn S. Environmental impact of

the NICU on de-velopmental outcomes. J Podiatry Nurs.

1998;13:279-89.

2. Altimier L, Phillips R. The neonatal

integrative develop-mental care model: Advanced clinical

applications of the seven core measures for neuroprotective

family-centered developmental care. Newborn Infant Nurs Rev.

2016;16: 230-44.

3. Madlinger-Lewis L, Reynolds L, Zarem

C, Crapnell T, Inder T, Pineda R. The effects of alternative

positioning on preterm infants in the neonatal intensive

care unit: A randomized clinical trial. Res Dev Disabil.

2014;35:490-7.

4. Vaivre-Douret L, Ennouri K, Jrad I,

Garrec C, Papiernik E. Effect of positioning on the

incidence of abnormalities of muscle tone in low-risk,

preterm infants. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2004;8:21-34.

5. Hughes AJ, Redsell SA, Glazebrook C.

Motor development interventions for preterm infants: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics.

2016;138:e20160147.

6. Ferrari F, Bertoncelli N, Gallo C, et

al. Posture and movement in healthy preterm infants in

supine position in and outside the nest. Arch Dis Child

Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2007;92:F386-90.

7. Visscher MO, Lacina L, Casper T, et

al. Conformational positioning improves sleep in premature

infants with feedingdifficulties. J Pediatr. 2015;166:44-8.

8. Jeanson E. One-to-one bedside nurse

education as a means to improve positioning consistency.

Newborn Infant Nurs Rev. 2013;13:27-30.

9. Zarem C, Crapnell T, Tiltges L, et al.

Neonatal nurses’ and therapists’ perceptions of positioning

for preterm infants in the neonatal intensive care unit.

Neonatal Netw J Neonatal Nurs. 2013;32:110-6.

10. POCQI-Learner-Manual.pdf [Internet].

Accessed Septem-ber 25, 2020. Available from: https://

www.newborn whocc.org/POCQI-Learner-Manual.pdf

11. Coughlin M, Lohman MB, Gibbins S.

Reliability and effectiveness of an infant positioning

assessment tool to standardize developmentally supportive

positioning practices in the neonatal intensive care unit.

Newborn Infant Nurs Rev. 2010;10:104-6.

12. Masri S, Ibrahim P, Badin D, Khalil

S, Charafeddine L. Structured educational intervention leads

to better infant positioning in the NICU. Neonatal Netw.

2018;37:70-7.

13. Spilker A, Hill C, Rosenblum R. The

effectiveness of a standardized positioning tools and

bedside education on the developmental positioning

proficiency of NICU nurses. Intensive Crit Care Nurs.

2016;35:490-7.

14. Charafeddine L, Masri S, Ibrahim P, Badin D, Cheayto S,

Tamim H. Targeted educational program improves infant

positioning practice in the NICU. Int J Qual Health Care.

2018;30:642-8.

|

|

|

|

|