|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2021;58:729-732 |

|

Etiology-Based

Decision-Making Protocol for Pediatric Cholelithiasis

|

|

Vikesh Agrawal, 1 Abhishek

Tiwari,1 Dhananjaya Sharma2,

Rekha Agrawal3

From 1Pediatric Surgery Division, 2Department of Surgery, and

3Department of Radiodiagnosis, Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose Medical

College, Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh.

Correspondence to: Dr Vikesh Agrawal, Department of Surgery, Netaji

Subhash Chandra Bose Medical College, Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh.

Email:

[email protected]

Received: July 12, 2020;

Initial review: July 07, 2020;

Accepted: September 26, 2020

Published online: January 02, 2021;

PII: S097475591600276

|

Objective: We reviewed hospital records

of pediatric cholelithiasis to develop an etiology-based

decision-making protocol. Method: This retrospective study was

conducted on consecutive pediatric cholelithiasis patients from July,

2014 to June, 2019 in a tertiary care center. Pediatric cholelithiasis

was classified according to etiology, and the outcome of

medical/surgical treatment was noted. Result: Data of 354

pediatric patients were analyzed. Commonest (56.2%) etiology was

idiopathic; followed by ceftriaxone pseudo-lithiasis (26.8%). Pigment

stones were associated with the highest rate of complications. Non-hemolytic

stones had a lower complication rate and a high rate of resolution with

medical therapy. Conclusion: Hemolytic and symptomatic stones

warrant an early cholecystectomy, whereas asymptomatic idiopathic

stones, ceftriaxone stones, and TPN-induced stones are candidates for

medical therapy under close observation.

Keywords: Ceftriaxone, Gall stone, Hemolytic anemia,

Management, Outcome.

|

|

P ediatric

cholelithiasis is increasingly being

diagnosed nowadays because of the use of

abdominal ultrasonography screening [1]. Its

prevalence in the Indian population has been reported to be rare

[2]. Common causes are idiopathic (30-54%), hemolytic disorders

(20-30%), and non-hemolytic causes (20-30%) such as ceftriaxone

therapy, total parenteral nutrition (TPN), obesity and cystic

fibrosis [3]. The treatment of choice for pigment stones is

surgery; however, guidelines and consensus are lacking for the

management of other stones, developed a simple etiology-based

decision-making protocol for pediatric cholelithiasis, after

analyzing our institutional data.

METHODS

We received hospital records from July, 2014

to June, 2019 of consecutive patients <18 years of age with

cholelithiasis/sludge in the pediatric surgical unit of a

tertiary center. Case records with incomplete data, and those

with a diagnosis of choledochal cyst were excluded.

Records were reviewed for demographic

information, symptoms (non-specific abdominal pain, right

hypochon-driac pain or biliary colic, nausea,vomiting,

jaundice), predisposing factors (body mass index, history of

fast food eating habit, acute gastroenteritis, dehydration,

hemolytic disorder, ceftriaxone injection, total parenteral

nutrition) and complications (acute cholecystitis, chronic

cholecystitis, choledocholithiasis, cholangitis, gall bladder

perforation). Fast food eating habit was defined as frequent

consumption of food containing a rich mix of refined sugars,

salt, and fats, and low in fibers. The child was considered

obese if BMI was >27 on IAP growth charts [4]. Ultrasonography

(USG) findings included floating hyperechoic lesion in gall

bladder with posterior acoustic shadow, echogenic sludge without

posterior acoustic shadow, gall bladder wall thickening (>3 mm

with 6 hours fasting), peri-cholecystic collection, common bile

duct (CBD) stone, and CBD and intrahepatic biliary radical

dilatation.

Cholelithiasis was classified according to

etiology: pigment stones (due to hemolytic disorders; positive

on hemoglobin electrophoresis), ceftriaxone pseudolithiasis

(cholelithiasis noticed within 21 days of >3 days of

intra-venous ceftriaxone therapy with a normal pre-ceftriaxone

ultrasound report), stone or sludge secondary to TPN (developing

after TPN); all others were labeled idiopathic. Hemoglobin

electrophoresis was done for all patients with cholelithiasis

diagnosed on ultrasound, and all patients with hemolytic

disorders underwent an ultra-sound to document hemolytic stones.

Cholecystectomy (open or laparoscopic;

depending on availability and patient condition) was performed

for all pigment stones (on diagnosis or presentation with a

complication). Medical therapy (Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) 25

mg/kg/day for 6 months) was advised for all non-hemolytic

stones. These patients were followed up with clinical

examination and ultrasound every 3 months. The stone resolution

was defined as an anechoic gall bladder on two consecutive

three-monthly ultrasounds. Patients developing complications

were dealt with in an emergent manner. Choledocholithiasis was

managed with endoscopic stone extraction and interval

cholecystec-tomy. Treatment is given

(routine/emergent/medical/cholecystectomy) and outcomes were

recorded.

Data analysis: Data analyses were

performed using an online Graphpad analyzer. All variables were

analyzed descriptively, and chi-square test or t-test

were used for statistical analysis. A value of P<0.05 was

considered significant.

RESULTS

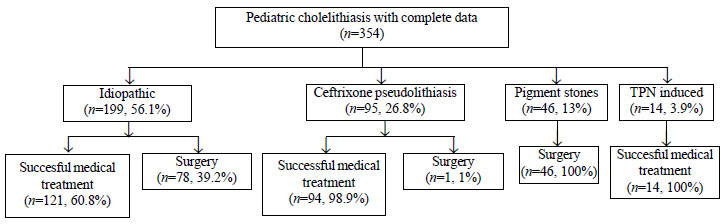

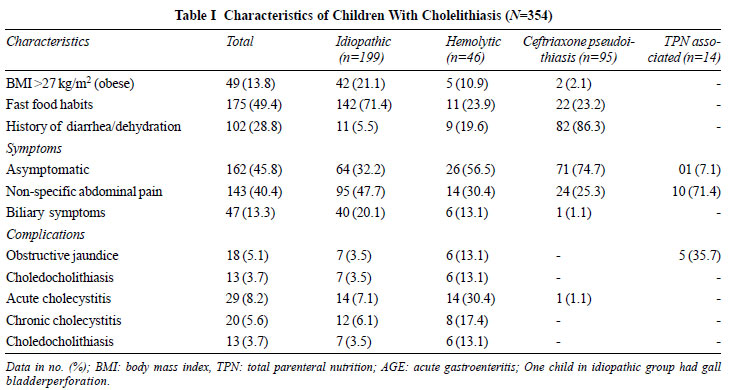

A total of 426 children (53.7% females) with

cholelithiasis fulfilled inclusion criteria, and were included

in the analysis (Fig. 1). Commonest (56.2%) etiology was

idiopathic; followed by ceftriaxone pseudolithiasis (26.83%).

The median (IQR) age was 6 (3-14) years. Incidence of obesity,

fast food habits, and biliary colic was highest in idiopathic

stones. Thirteen patients (13.7%) had a history of ceftriaxone

administration after abdominal surgery, associated with a

history of starvation for more than 48 hours. Most (45.8%)

patients were asymptomatic; non-specific abdominal pain was the

commonest (40.4%) symptom. The distribution of predis-posing

factors and symptoms among different etiologies is shown in

Table I. On ultrasound, the largest stone size was 2.5 cm,

and the mean size was not significantly different in all four

etiological types of cholelithiasis. Solitary stone was the

commonest (79.1%) presentation. Echogenic sludge without post

acoustic shadow was found in all cases of TPN-associated

cholelithiasis.

|

|

Fig. 1 Treatment provided for

various types of pediatric cholelithiasis.

|

|

| |

Pigment stones (n=46) were associated

with the highest rate of complications (Table I) and

underwent upfront elective cholecystectomy, planned

cholecystec-tomy, and emergent cholecystectomy (for gangrenous

cholecystitis) in 18, 22, and 6 patients, respectively. In

idiopathic pediatric cholelethiasis (39.2%) had to undergo

surgery because of biliary symptoms (37, 18.6%, elective

cholecystectomy), complications (34, 17.1%, 5 emergent

cholecystectomy), or failure of medical treat-ment in

asymptomatic pediatric cholelethiasis (7, 3.5%). Complications

viz. acute cholecystitis, chronic chole-cystitis and

choledocholithiasis were significantly higher in pigment stones

as compared to idiopathic stones (P=<0.001, P=0.02

and P=0.02, respectively). Medical management with UDCA

for 6 months was effective in 121 (60.8%) patients with

idiopathic cholelithiasis and all TPN-associated cases. TPN

stones were associated with the highest incidence of obstructive

jaundice. One patient underwent emergent cholecystec-tomy for

gall bladder perforation and biliary peritonitis. Gall-stone

pancreatitis was not seen in any patient.

DISCUSSION

Increasing prevalence of reversible

ceftriaxone-associated biliary pseudolithiasis is due to the

common use of ceftriaxone in children for abdominal infections

and peri-operatively in gastrointestinal surgery [5].

Ceftria-xone is excreted in bile where it gets 20-150 times

concentrated and readily forms a reversible insoluble salt with

calcium which precipitates into pseudo-stone formation [6].

Moreover, biliary stasis is known to occur in gastrointestinal

infection, starvation, after abdominal surgery, and

gram-negative sepsis [7]. History of admission for acute

gastroenteritis/dehydration or previous abdominal surgery with

the administration of ceftriaxone was common in our CP patients.

Compli-cations of cholelithiasis occur in 15-25% of pediatric

patients; hence, guidelines for expectant/medical/surgical

treatment are needed for its management [8,9]. Hemolytic stones

are advised cholecystectomy as the first line of treatment

because they do not respond well to medical dissolution therapy

and have a higher rate of complications due to impaction [8,10].

Ceftriaxone associated cholelithiasis and TPN induced pediatric

cholelithiasis, on the other hand, are known for their

reversible character and respond well to medical treatment [11].

UDCA is known to resolve PC in 19-37% of patients with

non-hemolytic stones [8,10,12]. Higher (60.8%) stone dissolution

with UDCA in the present study is unexplained.

Indications of cholecystectomy in idiopathic

pediatric cholelithiasis are less clear and the decision is

often based on clinical judgment, concerns for complications,

and the surgeons conviction (or lack of) in the efficacy of

UDCA [13]. In our study, 40% of idiopathic cholelithiasis

underwent surgery because of biliary symptoms or complications

or failure of medical treatment in asymptomatic patients;

supporting early surgery for symptomatic idiopathic stones. In

the present study, the majority of idiopathic and asympto-matic

idiopathic stones dissolved after medical treatment, suggesting

a specific role of medical therapy in avoiding surgery. However,

because of complications, medical treatment must be given under

close observation. An unnecessary cholecystectomy entails

needless risk and cost burden in a potentially dissolvable PC

[14]. Also, pediatric cholecystectomy is more challenging for

the surgeons because of its relative infrequency and the fact

that surgical volume might not help lower complication rates

[15]. The high incidence of ceftriaxone pseudo-cholelithiasis in

our study raises concerns about the common use of ceftriaxone in

pediatric practice. Awareness of this is important and

consideration should be given to the use of equivalent

antibiotic options.

Our algorithm (Web Fig. 1) allows a

pre-emptive approach to avert complications, the best

utilization of surgical options, and minimizes unnecessary

surgery. Formulation of our protocol is based on the analysis of

our data and lessons learned; it needs to be further tested in

different settings and in a prospective design.

Our etiology-based treatment protocol

developed with local data allows a judicious selection of

pediatric cholelithiasis patients for surgery. Hemolytic and

symptomatic stones warrant an early cholecystectomy.

Asymptomatic idiopathic stones, ceftriaxone stones, and

TPN-induced stones are candidates for medical therapy under

close observation.

Ethics approval: Netaji Subhash Chandra

Bose Medical College, Jabalpur, MP, India; No: IEC/NSCBMC/20/03,

dated September 27, 2020.

Contributors: VA, AT: concept, design,

definition of intellectual content, literature search, clinical

studies, data acquisition, data analysis, manuscript

preparation, editing and review; DS, RA: literature search,

clinical studies, data acquisition, data analysis, manuscript

preparation, editing, and review. All authors approved the final

version of the manuscript, and are accountable for all aspects

related to the study.

Funding: None; Competing interests:

None stated.

|

|

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS?

An etiology-based decision-making protocol for

pediatric cholelithiasis is proposed based on our

experience.

|

REFERENCES

1. Poddar U. Gallstone disease in

children. Indian Pediatr. 2010;47:945-53.

2. Ganesh R, Muralinath S,

Sankarnarayanan VS, Sathiya-sekaran M. Prevalence of

cholelithiasis in children a hospital-based observation.

Indian J Gastroenterol. 2005; 24:85.

3. Frybova B, Drabek J, Lochmannova J, et

al. Cholelithiasis and choledocholithiasis in children; risk

factors for development. PLoS One. 2018;13: e0196475.

4. Khadilkar V, Yadav S, Agrawal KK, et

al. Revised IAP Growth Charts for Height, Weight and Body

Mass Index for 5- to 18-year-old Indian Children. Indian

Pediatr. 2015;52: 47-55.

5. Bor O, Dinleyici EC, Kebapci M,

Aydogdu SD. Ceftriaxone-associated biliary sludge and

pseudochole-lithiasis during childhood: A prospective study.

Pediatr. Int. 2004;46:322-4.

6. Park HZ, Lee SP, Schy AL. Ceftriaxone-associated

gallbladder sludge. Identification of calcium-ceftriaxone

salt as a major component of gallbladder precipitate.

Gastro-enterology 1991;100:1665-70.

7. Palanduz A, Yalcin I, Tonguc E, et al.

Sonographic assess-ment of ceftriaxone associated biliary

pseudolithiasis in children. J Clin Ultrasound.

2000;28:166-8.

8. Kirsaclioglu TC, Çakır CB, Bayram G,

Akbıyık F, Işık P, Tunç B. Risk factors, complications and

outcome of cholelithiasis in children: A retrospective,

single-centre review. J Paediatr Child Health.

2016;52:944-9.

9. Poffenberger CM, Gausche-Hill M, Ngai

S, Myers A, Renslo R. Cholelithiasis and its complications

in children and adolescents: update and case discussion.

Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28:68-76.

10. Noviello C, Papparella A, Romano M,

Cobellis G. Risk factors of cholelithiasis unrelated to

hematological disorders in pediatric patients undergoing

cholecystec-tomy. Gastroenterology Res. 2018;11:346-8.

11. Rodríguez DA, Orejarena AP, Diaz BM,

et al. Gallstones in association with the use of ceftriaxone

in children. Ann Pediatr (Barc). 2014;80:77-80.

12. Gökçe S, Yıldırım M, Erdogan D. A

retrospective review of children with gallstone: Single-center

experience from Central Anatolia. Turk J Gastroenterol.

2014;25: 46-53.

13. Gamba PG, Zancan L, Midrio P, et al.

Is there a place for medical treatment in children with

gallstones? J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32:476-8.

14. Akhtar-Danesh G, Doumouras AG, Bos C,

Flageole H, Hong D. Factors associated with outcomes and

costs after pediatric laparoscopic cholecystectomy. JAMA

Surg. 2018;153:551-7.

15. Kelley-Quon Li, Dokey A, Jen HC, Shew SB. Compli-cations

of pediatric cholecystectomy: Impact from hospital experience

and use of cholangiography. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:73-81.

|

|

|

|

|