|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2019;56: 663-668 |

|

A Landscape Analysis of Human Milk Banks in

India

|

|

Ruchika Chugh Sachdeva 1,

Jayashree Mondkar2,

Sunita Shanbhag3,

Minu Manuhar Sinha3,

Aisha Khan3 and

Rajib Dasgupta4

From 1Maternal, Newborn, Child Health and

Nutrition, PATH, New Delhi; 2Department of Neonatology, and

3MBFI+ Project, Lokmanya Tilak Municipal Medical

College and Lokmanya Tilak Municipal General Hospital, Mumbai; and

4Department of Community Health, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New

Delhi; India.

Correspondence to: Dr Jayashree Mondkar, Professor

and Head, Department of Neonatology, Lokmanya Tilak Municipal Medical

College and Lokmanya Tilak Municipal General Hospital, Sion, Mumbai 400

022, India.

Email:

[email protected]

Received: October 26, 2018;

Initial review: January 28, 2019;

Accepted: June 20, 2019.

|

|

Objective: To evaluate the

existing status of human milk banks in India with reference to

infrastructure, human resources, funding mechanisms, operating

procedures and quality assurance. Methods: A pretested

questionnaire was administered to 16 out of 22 human milk banks across

India, operational for more than one year prior to commencing the study.

Results: 11 (69%) milk banks were in government or charitable

hospitals; only 2 (12.5%) were established with government funding. 8

(50%) had a dedicated technician and only 1(6%) had more than five

lactation counsellors. Milk was collected predominantly from mothers of

sick babies and in postnatal care wards followed by pediatric outpatient

departments, camps, satellite centers, and homes. 10 (63%) reported gaps

between donor milk demand and supply. 12 (75%) used shaker water bath

pasteurizer and cooled the milk manually without monitoring temperature,

and 4 (25%) pooled milk under the laminar airflow. 10 (63%) tracked

donor to recipient and almost all did not collect data on early

initiation, exclusive breastfeeding or human milk feeding.

Conclusion: Our study reports the gaps of milk banking practices in

India, which need to be addressed for strengthening them. Gaps include

suboptimal financial support from the government, shortage of key human

resources, processes and data gaps, and demand supply gap of donor human

milk.

Keywords: Breastfeeding, Breast

milk expression, Lactation, Storage, Prematurity.

|

|

I

ndia has the highest number of preterm births in

the world and breastfeeding rates are suboptimal [1,2]. Providing

breastmilk to these babies, especially those with very low birth weight

(VLBW), if they do not have access to their mother’s own milk due to

reasons such as mother’s sickness, separation, or temporary lactation

issues, is a challenge. This leaves them more vulnerable to infection

and death [3-5]. When mother’s milk is unavailable, pasteurized donor

human milk is recommended as the next best infant feeding option for

VLBW babies [6-8]. Human milk banks (HMBs) collect, pasteurize, test,

and store safe donor milk from lactating mothers, and provide it to

needy infants [9]. Though India’s first HMB was established in 1989,

HMBs in the country gathered momentum only in the last 3-4 years. [10].

Published data on status of these HMBs is not available. This study was

conducted to evaluate the existing status of HMBs with reference to

infrastructure, human resources (HR), funding mechanisms, operating

procedures and quality assurance in order to identify gaps to be

addressed to strengthen HMB systems.

Methods

This cross-sectional survey was conducted from August

2016 to February 2017, after obtaining permission of the Institutional

Ethics Committee at Lokmanya Tilak Municipal Medical College and General

Hospital, Mumbai. At the time of conducting the study, there were 30

HMBs in India. An online questionnaire was sent to 22 HMBs that had been

operational for more than one year at the time of start of this study.

The objective was shared telephonically with the HMB in-charge. The

questionnaire captured information on location of HMB, availability of

space, equipment and personnel, guidelines followed, operational

procedures, including donor recruitment, screening, milk collection,

processing, dispensing, utilization and infection control mechanisms,

and quality assurance measures followed during various processes,

including equipment maintenance, standard operating procedures and

hygiene protocol.

Six HMBs from different geographical zones were

visited for conducting onsite interviews of the HMB personnel to

reaffirm the data. The study team obtained informed consent of the

participants. No identifying information (names or addresses) of

respondents and facilities were retained in the electronic version of

the data records. Data were analyzed using MS Excel and primarily

included descriptive analysis, proportions and cross tabulations.

Results

Of the 22 eligible HMBs, 16 participated in the

study. Nine were run by government medical colleges, two by

charitable hospitals, and five by private hospitals. HMBs in charitable

and public hospitals were clubbed for analysis as their structure and

functioning was similar. All HMBs were operated by the Neonatology units

and were located near the neonatal intensive care units (NICU), except

one. The size of the milk processing area ranged from 100 to 862 square

feet and 200 to 300 square feet in public and private hospitals,

respectively. The setup cost of a HMB varied from INR 10,00,000 to

75,00,000. The establishment of 14 HMBs was funded by external agencies

(50% by the Rotary) and the remaining two by the government. The

recurring expenditure for ten centers were borne by the hospitals, three

were supported by the National Health Mission and two by private donors.

Availability of equipment for milk collection, storage, pasteurization

and equipment sterilization is shown in Table I. All HMBs

reported the use of electric hospital-grade breast pumps for milk

expression. In 10 HMBs, milk was stored and pasteurized in stainless

steel containers, and the remaining used polypropylene containers.

Indigenous shaker water bath was used for pasteurization in 13 HMBs, and

five used automated imported pasteurizer of which; two had both.

TABLE I Availability of Human Resources and Equipment in Public and Private Human Milk Banks (N=16)

|

Variables |

Public sector |

Private sector |

|

(n=11) |

(n=5) |

|

Human resource- Full-time staff |

|

Neonatologist/Pediatrician

|

11 (100) |

5 (100) |

|

Dedicated HMB manager |

2 (18) |

0 (0) |

|

Dedicated technician

|

7 (63.6) |

1 (20)

|

|

≥5 Lactation counselors

|

0 |

1 (20) |

|

Data entry operator |

2 (18) |

0 |

|

Human resource- Part time staff |

|

Technician |

0 (0) |

1 (20) |

|

Lactation counselors

|

0 (0) |

1 (20) |

|

Data entry operator |

1 (9) |

0 (0) |

|

Equipment |

|

Pasteurizer (shaker water bath) |

10 (91) |

3 (60) |

|

Pasteurizer (fully/semi-automatic)

|

3 (27.2) |

2 (40) |

|

Laminar air flow |

2 (18) |

2 (40) |

|

≥2 Electric breast pumps

|

11 (100) |

5 (100) |

|

>1 Deep freezer* (-20°C ±2°C) |

6 (54.5) |

3 (60) |

|

Separate deep freezers for raw and pasteurized milk |

5 (45.4) |

3(60) |

|

One freezer# |

4 (36.3) |

3(60) |

|

1 refrigerator

|

7 (63.6) |

4 (80) |

|

>1 refrigerator

|

3 (27.2) |

1 (20) |

|

All values in no.(%); #with separate shelves to

store raw milk, pasteurized milk, milk whose culture report was

awaited, and safe pasteurized milk. |

The HR available for running the HMBs are shown in

Table I. Doctors and nurses conducted counseling in three

HMBs that did not have any dedicated lactation counselors. Only two

(both private hospitals) provided breastfeeding counseling during

antenatal care. Eight HMBs had a full-time technician to undertake

pasteurization while in the rest, lactation counselors performed this

task. Milk culture in public hospitals was conducted by the hospital

laboratory services run by the Microbiology department and the private

facilities outsourced the testing. Almost all HMBs reported that they

did not collect data on early initiation, exclusive breastfeeding or

human milk feeding. Fourteen HMBs adhered to a set of guidelines, two

reported using the Human Milk Bank Association of North America (HMBANA)

guidelines [11], and one used the Perron Rotary Express Milk guidelines

(Australia) [12]. The remaining reported using their own standard

operating procedures based on HMBANA [10] or the Indian Academy of

Pediatrics guidelines [13].

Fifteen HMBs recruited donors whose babies were

admitted to the NICU and postnatal care (PNC) wards. Eight HMBS also

recruited donors from mothers visiting the well-baby clinics and the

pediatrics out-patients department (OPD). Five HMBs additionally

collected milk through community-based camps. Six HMBs also recruited

home-based donors, including one that exclusively used a home-based

model with the same mothers donating over a long period. Four HMBs had

satellite collection centers. All HMBs screened donor mothers; criteria

for acceptance included general clinical examination and negative blood

tests for HIV, Hepatitis B, and VDRL in antenatal period in the past six

months. Most HMBs pooled donor milk from multiple mothers. Two pooled at

the site of collection and four under the laminar airflow. All used the

Holder Pasteurization method. Four used fully automated pasteurizer and

the rest used shaker water bath and cooled the milk manually without

monitoring temperature. Three public HMBs conducted pre-pasteurization

culture to screen the milk. All conducted post-pasteurization cultures

and discarded milk with any positive microbiological test report. In

most HMBs, microbiological culture was done from individual containers.

Four HMBs pooled milk under the laminar flow, and conducted batch-wise

microbiological tests. Only one discarded milk as per the Bio Medical

Waste Management Guidelines

oof the hospital [14, and the rest discarded it in the sink.

Fourteen HMBs labeled the containers manually while

two labeled digitally. The labels contained information on date of

donation, batch number or container number, and date of pasteurization.

Four also mentioned expiry dates on the label. Four public and two

private HMBs stored preterm and term milk separately, and mentioned it

on the label. One private HMB also mentioned the nutritional content of

the milk. All bat one HMBs distributed pasteurized donor human milk on

prescription. Two private HMBs charged a processing fee to the

recipients. Frozen milk was transported in cold chain to the neonatology

units after which it was refrigerated and then thawed using warm water

baths before feeding. The duration between thawing and consumption was

about 2 to 6 hours in most HMBs. Ten HMBs tracked donor to recipient by

recording the donor milk batch and the container number (pool from

multiple mothers) against the recipient’s name. Only one tracked donor

milk from single mother to baby. All followed the processes outlined in

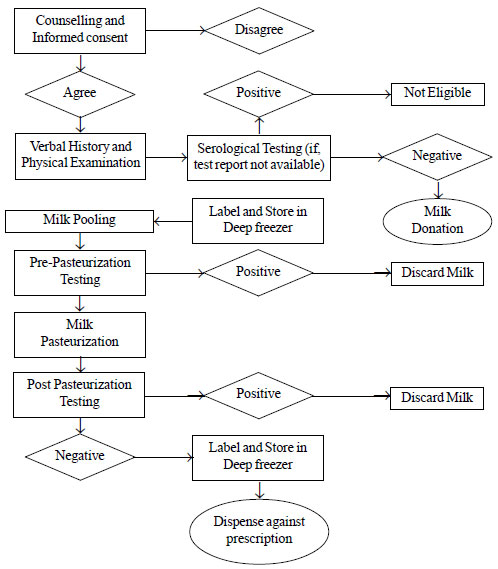

Fig. 1.

|

|

Fig. 1 Human milk bank processes in

the surveyed human milk banks.

|

All HMBs followed infection control measures. These

included donor mothers washing hands and cleaning their breasts with

water before expression. The containers in which milk was collected were

tightly secured to prevent any contamination during pasteurization.

Staff of most HMBs used disposable caps, face masks and gloves while

handling milk. The staff in all HMBs received orientation on hygiene

protocol. One HMB had a committee for infection control. The processing

room of 15 HMBs had restricted entry. 12 HMBs had equipment under Annual

Maintenance Contract (AMC); in the rest, only the pasteurizer was under

AMC. Fifteen HMBs had uninterrupted power supply.

Nearly one-fourth (range: 5%-38%) of mothers who

delivered in these hospitals donated milk. The annual number of donors,

volume of milk collected and recipient babies is presented in

Table II. Informed consent for donation was obtained in 13

facilities, and consent from recipient’s parents/guardians was obtained

in 14 facilities. Most provided donated milk to preterm babies,

sick full-term neonates in NICU, orphans, or babies of mothers with poor

lactation. Facilities reported 30% to 50% of the babies in NICU and 10%

to 20% babies in PNC ward required DHM for a variable period after

birth. Ten HMBs reported gaps between demand and availability of DHM.

Processed donor milk was used within a week or fortnight because of high

demand in most HMBs. DHM was fed to VLBW babies for 5-15 days on an

average during hospital stay.

TABLE II Annual Statistics of Donors and Recipients in Participating Human Milk Banks (N=16), 2015-16

|

Variables |

Median (Range) |

Public sector*

|

Private sector* |

|

Number of donors

|

600 (70-4000) |

1938 |

316 |

|

Volume of milk collected (liters) |

382 (30-1085) |

498 |

230 |

|

Volume of banked milk utilized (liters) |

293 (27-1047) |

469 |

174 |

|

Number of recipients

|

500 (80-3993) |

1480 |

261 |

|

*Average number at the participating centers. |

Discussion

This study offers an insight into the state of HMBs

in our country and serves as a baseline assessment of HMBs. A limitation

of this study was that onsite visits to all HMBs were not carried out

for confirmation of these findings. Moreover, about one-fourth of the

eligible HMBs did not participate in the survey, and few questions were

left unanswered by participating centers. Analysis was performed based

on the information shared by the facilities, and is prove to ‘reporting

bias’ .

We noted wide variations in the cost of establishing

HMBs across facilities. Imported automated pasteurizer and hospital

grade breast pumps accounted for the bulk of the capital costs.

Innovations are needed for developing indigenous and cost effective

models for these. equipments. Most HMBs were established with funding

from external agencies suggesting the need for a greater government

involvement for establishing and running HMBs, The Brazilian Network of

human milk banking has successfully demonstrated the effectiveness of a

government supported, nationalized, human milk banking as part of

integrated breastfeeding program [9]. There is a need to have more

lactation counselors and dedicated technicians in facilities to ensure

availability of quality lactation support to mothers, feeding data, and

safe DHM. Need for continuous support to mothers for breastfeeding has

been reiterated globally which in turn motivates mothers to donate milk

[15,16]. Our study analyzed that DHM can benefit five million babies

annually in India. Donor milk was collected from multiple sites in the

participating centers. However, community- and satellite centre-based

collection need to be encouraged to close the demand-supply gap as many

HMBs reported having short supply. Standardized guidelines on collection

of milk through camp and home based donors are needed.

More than half of the HMBs used stainless steel

containers for collection, which is unique to India. Steel has good

conductivity which may help in faster heating and cooling cycles and

should preserve milk nutrients better. However, such data comparing the

effect of steel, glass and polypropylene containers on the composition

of the stored milk are not available. The use of laminar airflow in more

HMBs will ensure aseptic pooling of milk. Pre-pasteurization culture of

milk, which is not being followed across all HMBs, should be implemented

uniformly.

The National Guidelines on Lactation Management

Centers in Public Health Facilities released by the Government of India

in 2017 positions HMBs as comprehensive lactation management centers

(CLMC) to universalize access to breast milk for babies. CLMCs support

breastfeeding and milk expression for sick babies, encourage kangaroo

mother care and provide pasteurized donor human milk to needy babies

lacking access to mother’s milk [17]. The gaps brought out by this study

should be addressed during the scaling up of HMBs/CLMCs as per the

national guidelines. Next steps in scaling up involve ensuring

sustainable funding and human resources, technology innovation, ensuring

uniformity of quality assurance procedures and standards including

operationalizing Hazard Analysis Critical Control Points systems,

accreditation, robust data tracking system and recording feeding data

for informed program decision making. Given the suboptimal status of

newborn nutrition in India, strengthening HMBs will contribute to

increasing access to lifesaving human milk for all babies, as part of

newborn nutrition and care.

Acknowledgments: Dr S Sitaraman, SMS Medical

College, Jaipur; Dr Poonam Singh, SMIMER, Surat; Dr Suchandra Mukherjee,

Institute of Post-Graduate Medical Education and Research and Seth

Sukhlal Karnani Memorial Hospital, Kolkata; Dr Kumutha, Government

Hospital for women and children, Chennai; Dr Kamalrathnam, Institute of

Child Health, Chennai; Dr. Sandhya S Khadse, BJ Government Medical

college and Sassoon General Hospital, Pune; Dr Shailaja Mane, Dr DY

Patil Medical College, Hospital and Research Centre, Pune; Dr Umesh

Vaidya, Sahyadri Hospital, Pune; Dr Rajan Joshi, Deenanath Mangeshkar

Hospital and Research Centre, Pune; Dr Vandana Kumavat, Rajiv Gandhi

medical college, Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Hospital, Thane; Dr Swati

Manerkar, LTMMC and GH, Mumbai; Dr Ruchi Nanavati, KEM Hospital, Mumbai;

Dr Sudha Rao, Wadia Hospital , Mumbai; Dr Rajesh Boob, Dr PDM Medical

College, Amaravati; Dr Jaishree Kulkurni; Fernandez Hospital, Hyderabad;

and Dr Raghuram Mallaiah; Fortis La Femme, New Delhi for their support

in facilitating data collection. Our special gratitude and

acknowledgment is extended to Kiersten Israel-Ballard Associate

Director, Maternal, Newborn and Child Health and Nutrition Global

Program, PATH and Sudip Mahapatra, Regional Monitoring and Evaluation

Specialist, PATH, for reviewing the research design and report. We also

extend our thanks to Paramita Kundu for her support in writing this

manuscript and Manu Bhatia for providing editorial support.

Contributors: RCS: conceptualized the research

design and protocol, provided inputs on the research tool, analysis and

interpretation of the data, and contribute to manuscript writing and

revised it; JM: administrative and technical guidance on the research,

design of research, and provided critical inputs on writing of the

manuscript; SS: contributed to research design, conceptualized the

research tool, and inputs to manuscript writing; MMS and AK: data

collection, analysis, manuscript writing; RD: analyzed the study

results, supported interpretation and contributed to the manuscript

writing and revision. All authors approved the final version of

manuscript, and are willing to be accountable for all aspects of study.

Funding: This project was funded through a grant

from the Margaret A. Cargill Philanthropies to PATH.

Competing Interests: None stated.

|

What This Study Adds?

•

The survey identified few gaps

in human milk banks in India that need to be addressed to

strengthen these facilities for better neonatal outcomes.

|

References

1. March of Dimes, PMNCH, Save the Children, WHO.

Born Too Soon: The Global Action Report on Preterm Birth. Eds Howson CP,

Kinney MV, Lawn JE. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2012.

2. International Institute for Population Sciences

(IIPS) and ICF. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015-16: India.

Mumbai: IIPS; 2017.

3. Panczuk J, Unger S, O’Connor D, Lee SK. Human

donor milk for the vulnerable infant: A Canadian perspective. Int

Breastfeed J. 2014;9:4.

4. Cregan MD, De Mello TR, Kershaw D, McDougall K,

Hartmann PE. Initiation of lactation in women after preterm delivery.

Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002; 81:870-7.

5. PATH. Policy Brief: Ensuring Equitable Access to

Human Milk for all Infants: A Comprehensive Approach to Essential

Newborn Care. Seattle: PATH; 2017. Global Breastfeeding Collective.

Available from: https://path. azureedge.net/media/documents/MNCHN_Equitable

AccesstoHumanMilk_PolicyBrief.pdf. Accessed November 19, 2017.

6. WHO. Every Newborn: An Action Plan to End

Preventable Deaths. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2014. Available

from:https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/127938/9789241507448_eng.pdf;jsessionid

=C3B 6F4BB283F8EA1A4606F4EE228CB21?sequence=1. Accessed January 8,

2018

7. Committee on Nutrition, Section on Breastfeeding,

Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Donor human milk for the high-risk

infant: Preparation, safety, and usage options in the United States.

Pediatrics. 2017;139:e20163440.

8. ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition, Arslanoglu S,

Corpeleijn W, Moro G, Braegger C, Campoy C, Colomb V, et al.

Donor human milk for preterm infants: Current evidence and research

directions. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;57:535-42.

9. DeMarchis A, Israel-Ballard K, Mansen KA, Engmann

C. Establishing an integrated human milk banking approach to strengthen

newborn care. J Perinatol. 2017;37:469-74.

10. Nangia S, Chugh RS, Sabharwal V. Human milk

banking: An Indian experience. Neoreviews. 2018;19:e201.

11. Human Milk Banking Association of North America.

Guidelines for the Establishment and Operation of a Donor Human Milk

Bank; 2015.

12. Hartmann BT, Pang WW, Keil AD, Hartmann PE,

Simmer K; Australian Neonatal Clinical Care Unit. Best practice

guidelines for the operation of a donor human milk bank in an Australian

NICU. Early Human Dev. 2007;83: 667-73.

13. Bharadva K, Tiwari S, Mishra S, Mukhopadhyay K,

Yadav B, Agarwal RK, et al. Human Milk Banking Guidelines Indian

Academy of Pediatrics. Indian Pediatr. 2014;51:469-74.

14. Government of India Ministry of Environment,

Forest and Climate change. Available from:http://www.moef.nic.in/sites/default/files/Final_vetted_BMW%20

Rules%202015. pdf. Accessed November 16, 2017.

15. Leung JCY, Yau SY. Perceptions of breastfeeding

mothers on breast milk donation and establishment of human breast milk

bank in Hong Kong: A Qualitative Study. International J Nursing.

2015;2:72-80.

16. Debortoli de MW, Christina PM, Fatima FMI,Palmira

FB. Representations of women milk donors on donations for the human milk

bank. Cadernos Saúde Coletiva. 2016;24:139-44.

17. Child Health Division, Ministry of Health and

Family Welfare, Government of India. National Guidelines on Lactation

Management Centres in Public Health Facilities. Available from:

http://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/programmes/IYCF/National_Guidelines_Lactation_

Management_Centres.pdf. Accessed November 16, 2017.

|

|

|

|

|