|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2019;56:643-646 |

|

Levetiracetam versus

Phenobarbitone in Neonatal Seizures – A Randomized Controlled

Trial

|

|

Vykuntaraju K Gowda 1,

Ayesha Romana2,

Niranjan H Shivanna3, Naveen

Benakappa3 and Asha

Benakappa2

From Divisions of 1Pediatric Neurology and 3Neonatology,

2Department of Pediatrics, Indira Gandhi Institute of Child

Health, Bangalore, Karnataka, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Vykuntaraju K Gowda, Division of Pediatric

Neurology, Department of Pediatrics, Indira Gandhi Institute of Child

Health, Bangalore, Karnataka, India.

Email: [email protected]

Received: April 01, 2018;

Initial review: August 20, 2018;

Accepted: June 20, 2019.

Trial Registration: Clinical Trial Registry of India

(CTRI/2018/04/013161).

|

Objective: To compare the efficacy and safety of

intravenous Levetiracetam and Phenobarbitone in the treatment of

neonatal seizures. Design: Open labelled, Randomized controlled

trial. Setting: Level III Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU).

Participants: 100 neonates (0-28 days) with clinical

seizures. Intervention: If seizures persisted even after

correction of hypoglycemia and hypocalcemia, participants were

randomized to receive either Levetiracetam (20 mg/kg) or Phenobarbitone

(20 mg/kg) intravenously. The dose of same drug was repeated if seizures

persisted (20 mg/kg of Levetiracetam or 10 mg/kg of Phenobarbitone) and

changeover to other drug occurred if the seizures persisted even after

second dose of same drug. Main outcome measures: Cessation of

seizures with one or two doses of the first drug, and remaining

seizure-free for the next 24 hours. Results: Seizures stoped in

43 (86%) and 31 (62%) neonates in Levetiracetam and Phenobarbitone

group, respectively (RR 0.37; 95%CI 0.17, 0.80, P<0.01). 10

neonates had adverse reactions in the phenobarbitone group (hypotension

in 5, bradycardia in 3 and requirement of mechanical ventilation in 2

neonates) while none had any adverse reaction in Levetiracatam group.

Conclusion: Levetiracetam achieves better control than

Phenobarbitone for neonatal seizures when used as first-line

antiepileptic drug, and is not associated with adverse drug reactions.

Keywords: Antiepileptic drugs, Convulsions, Management,

Neonate, Outcome.

|

|

S

eizures are the most common manifestation of

neurological insult during the neonatal period [1]. Etiology and

presentation of neonatal seizures are different from the children and

adults. The most common cause of symptomatic neonatal seizures is

hypoxic/ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) which affects approximately

1-2/100 live births [2,3]. There are no evidence-based guidelines for

the pharmacologic treatment of neonatal seizures and management is

highly variable. Phenobarbitone (PB) is the mainstay for neonatal

seizures treatment. The efficacy of PB in the complete resolution of

seizures varies between 33 and 77% [4]. Phenobarbitone can cause

neuronal apoptosis in vitro and have highly variable pharmacokinetics in

neonates [5-7].

Levetiracetam (LEV) may have a better safety profile

since it does not cause neuronal apoptosis in infant rodents [8]. A

recent review on the use of LEV in neonatal seizures revealed that

complete or near complete seizure cessation was achieved in 77% of LEV,

compared to 46% in PB group [9,10]. Literature pertaining to use of

levetiracetam in neonatal seizures is limited, and there is a lack of

randomized controlled trials. Hence we conducted this study with the

objective to compare the efficacy and adverse effects of LEV and PB in

the treatment of neonatal seizures.

Methods

This randomized controlled trial was conducted in the

level III NICU of a tertiary-care center over a period of 18 months

(November 2014 to April 2016). Outborn neonates (age 0-28 d) with

clinical seizures were enrolled in the study. Neonatal seizures were

clinically defined as abnormal, stereotyped and paroxysmal dysfunction

in the central nervous system (CNS), occurring within the first 28 days

after birth in full-term infants or before 48 weeks of gestational age

in preterm infants [11]. Neonates with hypoglycemia, hypocalcemia,

hypomagnesemia, those who received anticonvulsants prior to enrolment,

and those with major congenital malformations e.g., congenital

heart defects, neural tube malformations, diaphragmatic hernia,

choanal atresia, esophageal atresia, tracheoesophageal fistula,

omphalocele, gastroschisis, intestinal obstruction and imperforate anus)

were excluded.

Clinical details, seizure types and antiepileptic

administration, including the sequence of drugs, dosage, timing and

duration of therapy were recorded. Investigations included blood

glucose, serum calcium, magnesium, electrolytes, complete blood counts,

C- reactive protein, liver function tests, renal function tests,

arterial blood gas, lactate, ammonia, cranial ultrasono-graphy, Imaging

of brain, Electroencephalo-graphy (EEG), and metabolic and genetic

testing, whenever required to find out the cause for seizures.

Neonates with clinical seizures were randomly

assigned to receive either PB or LEV with a 1:1 allocation as per a

computer-generated randomization schedule and using sequentially

numbered, opaque and sealed envelopes. When an eligible neonate was

eligible to be enrolled, the envelope was opened by a clinician who was

not part of the study.

After ensuring patency of the airway, breathing and

circulation, blood sugar and ionic calcium level were performed. If

seizures persisted even after correction of hypoglycemia and

hypocalcemia, neonates were randomized for intervention to receive

either LEV (20 mg/kg) or PB (20 mg/kg) intravenously. Levetiracetam was

diluted in normal saline to achieve a concentration of 20 mg/mL and

administered intravenously at a rate of 1 mg/kg/min under

cardiorespiratory monitoring. If seizures terminated, LEV was continued

as maintenance at 20 mg/kg/day in two divided doses. If seizures

continued, another loading dose of LEV (20 mg/kg) was injected, and if

seizures still persisted, patient was switched over to PB. PB was

administered in the dose of 20 mg/kg diluted in 1: 10 normal saline

given intravenously slowly at the rate of 1 mg/kg/min under

cardiorespiratory monitoring; if seizures were terminated, it was

continued at 5 mg/kg/day in two divided doses as maintenance. Another

loading dose of 10 mg/kg of PB was administered in neonates who failed

to respond, and if seizures still persisted after two loading doses,

patient was switched over to LEV.

The proportion of patients achieving cessation of

seizures following the first or second dose of the drug (PB or LEV), and

those remaining seizure-free for next 24 hours was considered as the

primary outcome. Secondary outcome measure was the proportion of

patients experiencing adverse events. Termination of seizure was defined

clinically if there were no abnormal movement/eyeball deviation/nystagmus,

no change in heart rate, no change in respiration/saturation and

autonomic dysfunction. Adverse effects occurring within two hours of

drug administration, including desaturation, reduced respiratory rate,

increased ventilator support require-ment, arrhythmias, blood pressure,

or heart rate fluctuations by more than 10% compared to the previous 2

hours, or if vasopressors were initiated or increased, were recorded.

Increased ventilator requirement was considered, if requirement of tidal

volume more than 6 mL/kg on volume controlled-ventilator, peak

inspiratory pressure (PIP) more than 22 cm H 2O

in preterm and 23 cm H2O in

term, and mean airway pressure (MAP) of more than 12 cmH2O

on a pressure-controlled ventilator.

Informed consent was obtained from the parents on

pre-structured proforma as soon as possible after assessing for

eligibility. The study was approved by the institutional ethics

committee of Indira Gandhi Institute of Child Health, Bangalore. The

sample size required for this study was calculated as 100 (50 in each

group) with 95% two-sided significance ( a),

80% power, 1:1 randomization and a drop out of 15% assuming a difference

in proportion of outcomes between the groups as 31% (LEV 77% and PB 46%)

[12,13].

Statistical analyses: Continous variables were

compared between the two groups using independent samples t-test.

Termination of seizures at 24 hours and occurrence of adverse events

were compared by Chi-square test. Effect size and its 95% CI were

computed for the primary and secondary outcomes. P value of less

than 0.05 was considered as significant. The analyses were carried out

using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 20.0 software.

Results

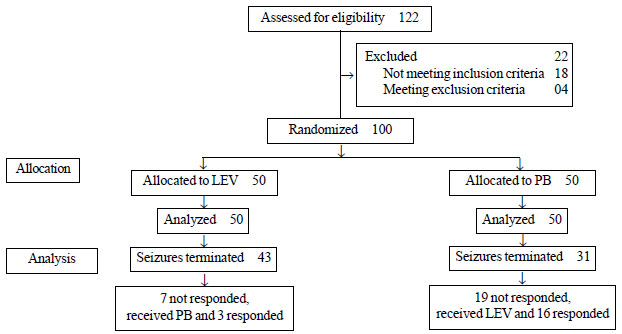

A total of 122 babies with clinical seizures were

assessed for eligibility during the study period; 22 were excluded and

50 neonates were randomized to each group (Fig. 1).

Baseline characteristics were comparable in the two groups (Table

I). The commonest etiology for seizures was hypoxic-ischemic

encephalopathy (HIE). Focal clonic seizures constituted the most common

type of seizure in the study population.

PB: Phenobarbitone; LEV: Levetiracetam

|

|

Fig. 1 Flow of participants in the study.

|

TABLE I Comparison of Baseline Characteristics of the Study Groups

|

Characteristics |

Levetiracetam |

Phenobarbitone |

|

(n=50) |

(n=50) |

|

Age (d), mean (SD) |

9.8 (8.50) |

8 (8.33) |

|

Male, n (%) |

28 (56) |

28 (56) |

|

Mode of delivery, n (%) |

|

Vaginal |

35 (70) |

36 (72) |

|

Caesarian |

15 (30) |

14 (28) |

|

Gestation, n (%) |

|

Term |

40 (80) |

42 (84) |

|

Preterm |

10 (20) |

08 (16) |

|

Birth weight (kg) , mean (SD) |

2.56 (0.64) |

2.73 (0.64) |

|

Etiology of seizures, n (%) |

|

HIE |

20 (40) |

24 (48) |

|

Neonatal sepsis/Meningitis |

18 (36) |

15 (30) |

|

Intracranial hemorrhage |

3 (6) |

2 (4) |

|

Benign neonatal epilepsy syndrome |

2 (4) |

1 (2) |

|

Malignant neonatal epilepsy syndrome |

1 (2) |

1 (2) |

|

Cortical malformation |

1 (2) |

1 (2) |

|

IEM |

1 (2) |

2 (4) |

|

Unknown |

4 (8) |

4 (8) |

|

HIE: Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, IEM: Inborn

errors of metabolism. |

Following first dose of drug, seizures stopped in 30

(60%) neonates in LEV group, and 25 (50%) neonates in PB group. In the

LEV group, there was a cessation of clinical seizures (and remaining

seizure free at 24 h) in 43 (86%), and in the PB group, it was 31 (62%)

after one or two doses (P<0.001). Seizure control was better (RR

0.37; 95% CI (0.17, 0.80) in the LEV group.

A total of 10 adverse events were observed in the PB

group and none in LEV group. Various adverse events noted in the PB

group were; hypotension in 5 neonates, bradycardia in 3 neonates and

requirement of mechanical ventilation in 2 neonates.

Three out of the seven neonates who did not respond

to LEV, responded to PB. Among the 19 neonates who did not respond to

PB, 16 showed seizure cessation with LEV. In the LEV group, 47 were

discharged, two left against medical advice, and one died. In the PB

group, 46 neonates were discharged and four left against medical advice.

Discussion

In the present study, we documented better

anticonvulsant efficacy and safety of LEV in comparison to PB as a

first-line antiepileptic drug in neonatal seizures. A higher proportion

of neonates had a cessation of seizures in LEV group as compared to PB

group. There were no adverse drug reactions noted in the neonates who

received LEV in the present study whereas, 10 of the neonates in the PB

group developed adverse drug reactions. The efficacy of LEV has been

earlier demonstrated in a study by Ramantani, et al. [13]

, in which 30 (78%) out of 38 infants were

seizure-free after receiving LEV. In study by Khan, et al. [14],

19 (86%) of the 22 neonates

demonstrated seizure cessation within 1 hour of administration. In a

systematic review of the efficacy of LEV in neonatal seizures, complete

or near-complete seizure cessation was achieved in 37/48 (77%) who

received LEV as first-line drug, and 24/52 (46%) of the ones with PB as

first-line AED [10]. These results show that LEV is at least as

effective as PB in the control of neonatal seizures as a first-line

agent. However, in a study by Abend, et al. [15], LEV was

associated with seizure improvement within 24 hours in only 8 (35%) of

23 neonates. The low response to LEV in this study could be due to the

usage of LEV as first-line anti-epileptic drug in only one neonate in

the study. Few other studies [10,16] have documented good seizure

control with LEV when it was used as a second- or third-line agent in

control of neonatal seizures. The safety of LEV in neonates has also

been documented in previous studies [13,15-17].

The limitation of our study was that we did not

perform electroencephalographic monitoring to document cessation of

seizure activity. However, in most of the neonatal units, especially

with limited resources, clinical control of seizures is usually the only

guide to treatment. Thus, despite this limitation, the generalizability

of our study for such settings is reasonable. Lack of long-term

follow-up and inability to perform therapeutic drug levels of PB and LEV

were the other limitations of the present study. The sample size of our

study was also inadequate for the outcomes related to various adverse

effects.

We conclude that levetiracetam is an effective and

safer alternative to phenobarbitone in the management of neonatal

seizures, as a first-line AED.

Contributors: VR: conceptualization of study, and

critical inputs to manuscript for important intellectual content; AR:

data collection and writing the manuscript; NS and NB: data collection

and analysis, and critical inputs to manuscript writing; AB: supervision

of the work and revision of manuscript.

Funding: None; Competing interests:

None stated.

|

What is Already Known?

•

Phenobarbitone currently

represents the antiepileptic drug of choice in the management of

neonatal seizures.

What this Study Adds?

•

Levetiracetam is an effective and safer alternative to

phenobarbitone as a first line drug in the management of

neonatal seizures.

|

References

1. Thibeault-Eybalin MP, Lortie A, Carmant L.

Neonatal seizures: Do they damage the brain? Pediatr Neurol.

2009;40:175-80.

2. Ronen GM, Penney S, Andrews W. The epidemiology of

clinical neonatal seizures in Newfoundland: a population-based study. J

Pediatr. 1999;134:71.

3. Saliba RM, Annegers JF, Walker DK, Tyson JE,

Mizrahi EM. Incidence of neonatal seizures in Harris County, Texas,

1992-1994. Am J Epidemiol. 1999; 150:763.

4. Van Rooij LG, Hellström-Westas L, deVries LS.

Treatment of neonatal seizures. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med.

2013;18:209-15.

5. Bartha AI, Shen J, Katz KH, Mischel RE, Yap KR,

Ivacko JA, et al. Neonatal seizures: multicenter variability in

current treatment practices. Pediatr Neurol. 2007;37:85-90.

6. Wheless JW, Clarke DF, Arzimanoglou A, Carpenter

D. Treatment of pediatric epilepsy: European expert opinion, 2007.

Epileptic Disord. 2007;9:353-412.

7. Painter MJ, Scher MS, Stein AD, Armatti S, Wang Z,

Gardiner JC, et al. Phenobarbital compared with phenytoin for the

treatment of neonatal seizures. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:485-9.

8. Manthey D, Asimiadou S, Stefovska V, Kaindl AM,

Fassbender J, Ikonomidou C, et al. Sulthiame but not

levetiracetam exerts neurotoxic effect in the developing rat brain. Exp

Neurol. 2005;193:497e503.

9. Mruk AL, Garlitz KL, Leung NR. Levetiracetam in

neonatal seizures: A review. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2015;20:76-89.

10. McHugh DC, Lancaster S, Manganas LN. A systematic

review of the efficacy of levetiracetam in neonatal seizures.

Neuropediatrics. 2018;49:12-17.

11. Han JY, Moon CJ, Youn YA, Sung IK, Lee IG.

Efficacy of Levetiracetam for neonatal seizures in preterm infants. BMC

Pediatr. 2018;18:131.

12. Boylan GB, Rennie JM, Pressler RM, Wilson G,

Morton M, Binnie CD. Phenobarbitone, neonatal seizures, and video EEG.

Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2002;86:165-70.

13. Ramantani G, Ikonomidou C, Walter B, Rating D,

Dinger J. Levetiracetam: Safety and efficacy in neonatal seizures. Eur J

Paediatr Neurol. 2011;15:1-7.

14. Khan O, Chang E, Cipriani C, Wright C, Crisp E,

Kirmani B. Use of intravenous levetiracetam for management of acute

seizures in neonates. Pediatr Neurol. 2011;44:265-9.

15. Abend NS, Gutierrez-Colina AM, Monk HM, Dlugos

DJ, Clancy RR. Levetiracetam for treatment of neonatal seizures. J Child

Neurol. 2011;26:465-70.

16. Rakshasbhuvankar A, Rao S, Kohan R, Simmer K,

Nagarajan L, J Clin Neurosci. 2013;20:1165-7.

17. Koppelstäetter A, Buhrer C, Kaindl AM. Treating

neonates with levetiracetam: A survey among German university hospitals.

Klin Pediatr. 2011;223:450-2.

|

|

|

|

|