|

Clinicopathological conferences |

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2018;55:693-697 |

|

An Infant with

Respiratory Distress and Loose Stools

|

|

Poojitha Reddy 1,

Devika Laishram2,

Ankur Kumar Jindal2,

Kirti Gupta3 and

Amit Rawat2

From 1Department of Pathology, 2Allergy

Immunology Unit, Department of Pediatrics, and 3Department of

Histopathology, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and

Research, Chandigarh, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Kirti Gupta, Professor, Department of

Histopathology, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and

Research (PGIMER), Chandigarh 160 012, India.

Email:

[email protected]

|

We present the case of a 3-month-old girl who was

admitted with complaints of loose stools and respiratory distress. She

also had a history of rash and alopecia. Laboratory investigations

revealed lymphopenia with reduced immunoglobulin G and immunoglobulin A.

Lymphocyte subset analysis by flow cytometry revealed T-B+NK+ severe

combined immunodeficiency (SCID). She died due to severe pneumonia,

shock and pulmonary hemorrhage. Autopsy findings revealed disseminated

cytomegalovirus infection in the lung, liver, adrenals and heart. Thymus

was found to be dysplastic and showed characteristic histopathologic

features of SCID.

Keywords: Alopecia, Cytomegalovirus, Diarrhea, Lymphopenia,

Pneumonia, Severe combined immunodeficiency.

|

|

Clinical Protocol

History: A 3-month-old girl, product of 3rd

degree consanguineous marriage presented with history of generalized,

erythematous, maculopapular rash all over body that developed at one

month of age. Rash was associated with skin peeling and it resolved

spontaneously in one month. She subsequently had progressive loss of

scalp hair and eyebrows. She also had bilateral purulent ear discharge

since the age of 2 months associated with cough, respiratory distress

and loose stools. Child was admitted twice for these complaints in a

nearby hospital and was managed with IV antimicrobials. She had received

BCG vaccination at 1 month of age, however, she developed no reaction at

the BCG site.

Clinical examination: She had tachycardia (heart

rate 150/minute), tachypnea (respiratory rate-62/minute), pallor,

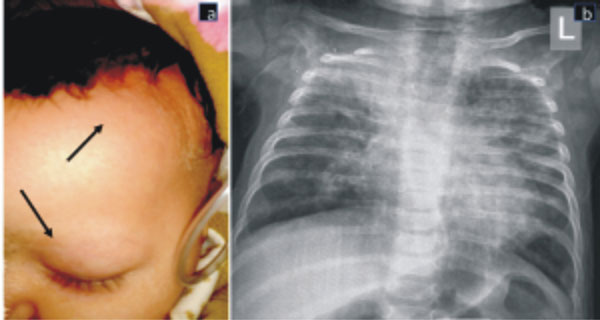

alopecia with loss of eyebrows (Fig. 1), skin peeling in

the left axilla, no BCG scar, coarse crepitation in bilateral chest and

hepato-splenomegaly. Initial clinical possibilities were Human

Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection, Severe Combined Immunodeficiency

(SCID) with maternal engraftment, congenital Cytomegalovirus (CMV)

infection and Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

|

| (a) |

(b) |

|

Fig. 1 Alopecia over left fronto-parietal

region and loss of eyebrows (arrows) (a); chest X-ray (anteroposterior

view) showing interstitial pattern of infiltrates in both lungs,

predominantly perihilar. Homogenous opacity in right upper lung

fields and absent thymic shadow (b).

|

Laboratory investigations: She had anemia

(hemoglobin- 83 gm/L), lymphopenia (white cell count 16.3×10 9/L,

differential counts P79L16M5,

absolute lymphocyte counts 2.6×109/L),

transaminitis (alanine aminotransferase 94 IU/L and aspartate

aminotransferase 303 IU/L), and a high C-reactive protein (39.6 mg/L).

Serial arterial blood gas analysis revealed hypoxemia and hypercarbia.

Chest X-ray revealed bilateral non-homogeneous opacities

predominantly distributed in the peri-hilar region. (Fig. 1b).

Ultrasound abdomen showed ileo-ileal intussusception. Contrast enhanced

Computed Tomography (CECT) chest revealed multiple bilateral pulmonary

nodules with consolidations. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) serology

was non-reactive, Fine needle aspiration cytology from axillary lymph

node showed reactive lymphoid hyperplasia, gastric lavage for acid fast

bacilli and pneumocystis jiroveci stain was negative, serum

galactomannan index was elevated (5.8, normal <0.5), blood culture was

sterile, IgM Cytomegalovirus (CMV) serology and CMV DNA PCR was

positive.

Immunological investigations (Table I):

She had undetectable IgG and IgA and normal IgM; nitroblue tetrazolium

(NBT) dye reduction test and dihydrorhodamine 123 (DHR) assay were

normal; lymphocytes subsets showed reduced CD3+ T cells (32% of all

lymphocytes), normal CD19+ B cells (29% of all lymphocytes) and normal

CD56+ NK cells (39% of all lymphocytes); CD 127 (IL-7Rá) expression was

reduced (Web Fig.1a and 1b); CD45RA

expression on CD3+T cells and CD8+T cell was reduced suggestive of low

naďve T cells; CD45RO expression on CD3+T cells and CD8+T cells was

elevated suggestive of increased memory T cells (likely to be of

maternal origin).

TABLE I Laboratory Investigations of Index Case

|

Investigation |

Results |

Normal reference

|

|

|

range |

|

IgG (mg/dL) |

<201 |

240-880 |

|

IgA (mg/dL) |

<17 |

10-50 |

|

IgM (mg/dL) |

90 |

20-100 |

|

CD3+ T cells |

32.68% |

51-77.6% |

|

CD19+ B cells |

29.79% |

11-41% |

|

CD16/56+ NK cells |

33.41% |

3-14% |

|

CD45RA expression on CD3+T cells

|

2.23% |

67.83% |

|

CD45RO expression on CD3+T cells |

94.7% |

31.18% |

|

CD45RA expression on CD8+T cells |

5.18% |

74.54% |

|

CD45RO expression on CD8+T cells |

93.6% |

22.35% |

|

CD-127 (IL-7Ra) expression on CD3+ |

16.5% |

53.95%

|

|

T lymphocytes |

|

(normal control) |

Course and management: Child was administered

intravenous ceftriaxone and cloxacillin, however, antimicrobials were

upgraded to vancomycin, imipenem, cotrimoxazole, amphotericin B and

anti-tubercular therapy (ATT). ATT was initiated empirically as the

child had received BCG vaccination at birth and pneumonia could be a

manifestation of disseminated BCG disease [1]. Oxygen therapy was

administered through nasal prong oxygen initially but on 6 th

day of hospital stay, child was intubated and kept on manual

intermittent positive pressure respiration. She was also given 5 grams

of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG); fluid bolus and inotropes

(dopamine and dobutamine) for shock and irradiated packed cell

transfusion. She also developed pneumothorax requiring intercostal

drainage tube and massive pulmonary hemorrhage leading to cardiac arrest

and death.

Unit’s final diagnosis: Severe combined

immunodeficiency (T-B+NK+) with IL-7R alpha deficiency with maternal

engraftment, severe pneumonia, sepsis, septic shock and pulmonary

hemorrhage.

Discussion

Clinical discussant: We have a 3-month-old girl

with history of consanguinity presenting with rash, alopecia, skin

peeling, otitis media, pneumonia, loose stools and intussusception. She

had anemia, lymphopenia, transaminitis, elevated galactomannan index,

positive CMV DNA PCR, multiple pulmonary nodules on CT chest, low

immunoglobulins, T-B+NK+ phenotype on lymphocyte subsets, low naďve T

cells and reduced IL-7R a

expression on T cells.

Case analysis can be discussed with respect to the

underlying disease; the etiology for pneumonia; the cause for

Intussusception; and the terminal events.

The clinical presentation is suggestive of an

underlying immune defect. After ruling out HIV infection, the most

likely underlying diagnosis is SCID, as she was born to a

consanguineously married couple and presented within the first 2 months

of age with severe pneumonia, otitis media, alopecia (likely due to

maternal engraftment), and absence of BCG scar. Laboratory

investigations revealed lymphopenia, hypogamma-globulinemia, low CD3+ T

cells, naďve T cells and absence of thymic shadow on chest X-ray.

She fulfills the European society of immunodeficiency (ESID) registry

working definition for clinical diagnosis of SCID.

SCID has four phenotypes based on the presence or

absence of B and NK cells (T-B-NK+; T-B-NK-; T-B+NK-; T-B+NK+). Our

child had T-B+NK+ phenotype and she also had reduced expression of IL-7R a.

She had features of maternal engraftment (i.e.

presence of maternal T lymphocytes in the circulation leading to

manifestations that are like graft versus host disease). Most common

manifestation of maternal engraftment is skin involvement with eczema,

erythema, alopecia and skin peeling; followed by liver involvement (with

mild to moderate elevation of liver enzymes) and gastrointestinal tract

involvement (diarrhea). Index child has history of generalized erythema

and peeling of skin and alopecia. She also had elevated liver enzymes.

The etiology for pneumonia is likely to be

polymicrobial. Invasive fungal infection can be considered in view of

positive serum galactomannan index, CMV can be considered in view of

positive CMV DNA PCR in the blood and suggestive radiological findings.

Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia can also be considered in view of

radiological findings. As she received BCG vaccination, so a possibility

of disseminated BCG infection with pneumonia can also be considered.

She also had intussusception as evident on ultrasound

of the abdomen. The intussusception in this age group would most likely

be related to infections which could be a viral or bacterial infection.

In the index child, Mycobacterium bovis and CMV can be

considered. BCG infection leading to recurrent intussusception has

previously been reported in SCID [2].

The cascade of terminal event can be summarized as

SCID leading to severe pneumonia and polymicrobial sepsis that has led

to multiorgan dysfunction and pulmonary hemorrhage finally causing shock

and death.

Therefore, the final diagnosis is severe combined

immunodeficiency (T-B+NK+ phenotype with IL-7R a

deficiency) with pneumonia (CMV, Aspergillus, Pneumocystis jiroveci),

pulmonary hemorrhage and intussusception (Mycobacterium bovis or

CMV)

Senior resident of the treating unit: The

diagnosis of SCID is not in doubt here and other differentials diagnosis

that were considered can easily be excluded based on the immunological

investigations. I expect severe depletion of T cells in the thymus;

changes of GVHD in skin and gut and CMV or Mycobacterium bovis in

lungs and gastrointestinal tract.

Physician 1: Was fundus checked in the index case

to look for evidence of CMV retinitis?

Senior resident of the treating unit: The fundus

evaluation was done and there was no evidence of CMV retinitis.

Pediatrician 1: Mycobacterium bovis

infection secondary to BCG vaccination often produces skin lesions and

fine needle aspiration from these skin lesions can yield acid fast

bacilli (AFB). However, there were no skin lesion in the index child.

Gastric lavage for AFB was negative. However, it is not always necessary

to find AFB on gastric lavage. Index child had alopecia and loss of

eyebrows that was suggestive of maternal engraftment or Omenn syndrome.

Pediatrician 2: The syndrome of SCID should be

suspected if the child presents within the first few months of life with

rash and polymicrobial sepsis which is not responding to antimicrobials.

If hemogram shows lymphopenia as in the index child, SCID should be

considered. The phenotype of SCID can be evaluated with the help of flow

cytometry. Index child had an unusual phenotype i.e. T-B+NK+.

Pathology Protocol

A complete autopsy was performed on this 3-month-old

girl. The peritoneal cavity revealed ascites with 270 mL of

straw-colored fluid. The other serous cavities were within normal

limits.

Thymus weighed 2 g (normal weight for this age is 3

g) and revealed maintained lobular architecture on gross examination.

However, on microscopy cortico-medullary distinction was lost and there

was absence of Hassall’s corpuscle. These features are consistent with

thymic dysplasia. CD3 immunostain revealed reduction in T-lymphocytes,

however, the thymocytes were preserved as highlighted by pan-cytokeratin

(Web Fig. 2 a-d).

All sampled lymph nodes showed depletion of lymphoid

population. T cell zones i.e. paracortical and interfollicular regions

showed reduction in T lymphocytes as highlighted by CD3. CD20 performed

revealed normal population of B lymphocytes (Web Fig. 2e-g).

Peyer’s patches were hypertrophic with relative preservation of B cell

zone (Web Fig. 2h). However, there was marked

reduction of T cell zone. Spleen weighed 20 g (normal for this age is 25

g). On histology, there was mild congestion of the red pulp with

preservation of B cell zone and relative reduction of periarteriolar T

cell zone.

Both the lungs were heavy (weight 250 g) with dull

pleural surface. Many subpleural nodules were identified. The cut

surface showed diffuse areas of hemorrhagic consolidation in all the

lobes, bilaterally. Tracheo-bronchial tree was unremarkable.

Microscopically, there was interstitial widening with mild

lymphomononuclear infiltrate along with many large cells protruding into

the alveolar lumen. Many cytomegalovirus inclusions (CMV) were noted

within alveolar pneumocytes and endothelial cells. These cells

demonstrated nucleomegaly along with presence of basophilic to

amphophilic inclusions in the nucleus and a perinuclear halo (Web

Fig. 2i). Immunostaining for CMV revealed the burden of

infection. Similar inclusions were also noted in the bronchial

epithelial cells and endothelial cells of blood vessels. Adjacent areas

of lung parenchyma showed diffuse alveolar hemorrhages and focal hyaline

membrane formation. No granulomas were identified and Ziehl-Neelsen

stain for acid fast bacilli (AFB) was negative. PAS stain performed did

not reveal any fungal hyphae and gram’s stain performed did not reveal

any micro-organisms.

Adrenals examined showed foci of necrosis with the

presence of CMV inclusions within the necrotic foci. Heart (weight 30 g)

was unremarkable grossly. However, few endothelial cells with the

interstitial vessels in the myocardium showed presence of CMV inclusion

which was confirmed on immunohistochemistry. Liver (weight 450 g) was

unremarkable on gross examination. Cut surface was pale yellow to greasy

in appearance. On microscopy, diffuse macrovesicular steatosis

predominantly involving the zone 1 and zone 2 areas with relative

preservation of zone 3 hepatocytes was noted. Few scattered CMV

inclusions were also noted in the Kupffer cells of the sinusoids which

was confirmed on immunohistochemistry. Rest of the organs including

brain, kidneys, bone marrow, stomach, esophagus, skin, thyroid, skeletal

muscle were unremarkable grossly and microscopically.

Final autopsy diagnosis:

• Thymic dysplasia

• Disseminated CMV infection – Lung

(predominant), Adrenal, Liver, Heart

• Macrovesicular steatosis

• Intussusception of small intestine

Senior resident of the treating unit: There is

perfect correlation between flow cytometry reports and pathology

findings in lymph nodes. B cells were present in the flow cytometry

report and were also found in the lymph nodes. In many types of SCID,

the B cells are absent in blood and there we see depletion of B cell

zone in the lymph nodes. Was any organism isolated at the site of

intussusception?

Pathologist 1: No organism was seen at the site

of intussusception. The intussusception was likely due to hyperplasia of

Peyer’s patches.

Physician 1: Was flow cytometry analysis done for

the parent’s sample and were parents counselled about future

pregnancies.

Senior resident of the treating unit: Flow

cytometry analysis of parent’s sample is not usually done in cases of

SCID. Molecular analysis will be done for both child and parents.

Parents have been advised to avoid further pregnancy till the genetic

confirmation, following which a prenatal diagnosis will be offered.

Pediatrician 3: This is an autosomal recessive

SCID and parents are likely to be the carriers. So, flow cytometry is

not useful in diagnosing carrier status which can only be diagnosed with

molecular analysis.

Pathologist 2: In the year 1980s, these types of

cases did not fit into any clinical diagnosis, these infants will have

infections like CMV, PCP with hypogammaglobulinemia and lymphopenia.

However, the level of investigations was not as extensive as they are

now. One thing that was pursued extensively at that time was the

possibility of AIDS. Extensive investigations were done on thymus and

lymphoid system. Serial sections of thymus were done which demonstrated

isolated Hassall’s corpuscles and normal blood vessels. In thymic

dysplasia thymus are abnormally small with small blood vessels, lobules

are shrunken and no lymphoid tissue in cortex and medulla which are

classical of SCID.

Pathologist 1: Lymphoid cells in the thymus were

due to maternal engraftment and it is difficult to differentiate

lymphoid cells from maternal origin or from the child. CMV infection is

most likely acquired as the major bulk of CMV disease was in lung and

not in liver.

Discussion

SCID is the most severe form of combined

immunodeficiency with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 58,000 live births

[3]. It is characterized by a block in T lymphocyte differentiation and

variable depletion of B and NK cells depending on the subtype of SCID

[4,5]. There are four major subtypes of SCID based on presence or

absence of B or NK cells. The index patient had T-B+NK+ SCID. This can

be caused by mutation in IL-7R a

or CD45 gene. Index patient had reduced expression of IL-7Ra.

SCID due to mutation in IL-7Ra

gene accounts for approximately 10% of all cases [6].

Children with SCID often present with recurrent

infections with an onset before the age of 6 months. Oral candidiasis,

persistent diarrhea, pneumonia and failure to thrive are the most common

presenting manifestations. There are no major differences between

various subtypes of SCIDs in their initial presentation; however, ADA

deficiency SCID tends to have severe lymphopenia (<0.5×10 9/L)

and hence very early and severe presentation. Common opportunistic

organisms seen in these patients are Pneumocystis jiroveci,

Aspergillus sp. and Cytomegalovirus. Majority of children die within

the first 2 years of life if not treated adequately. Respiratory tract

infections are common in patients with SCID and CMV pneumonia may be the

first presenting manifestation [7]. A persistent CMV respiratory

infection may be clinically or radiologically indistinguishable from

other respiratory viral infections. Index patient had interstitial

infiltrates on chest radiograph and positive CMV DNA PCR in blood and

autopsy revealed CMV infection in lung as well as in liver, heart and

adrenal glands.

In almost all subtypes of SCID, thymus is usually

atrophic [8] and poorly visualized on a chest radiograph [9] as was seen

in the index patient also. The histopathology of thymus in SCID

demonstrates depletion of lymphocytes and lack of differentiation of

thymic epithelium. Poor differentiation of thymic epithelium is

responsible for the absence of Hassall’s corpuscles and is on one of the

most important histopathological feature of SCID [10]. Thymic epithelium

has very important role in the normal differentiation of T-cell

population and due to thymic dysplasia in SCID, T-cell differentiation

is impaired [11].

Intussusception can have variable etiology (i.e.

viral, bacterial or protozoal infections and benign or malignant

tumors). As compared to adults in whom a definite lead point is often

found, it is rather uncommon to find a cause in children. Hyperplasia of

Peyer’s patches may be seen in upto a third cases of idiopathic

intussusception [12]. Index patient also had similar pathology at the

site of intussusception.

Contributors: PR: pathology protocol

presentation, writing of manuscript, review of literature; DL: clinical

protocol presentation, writing of manuscript, review of literature; AKJ:

clinical protocol presentation, writing of manuscript, editing of

manuscript, review of literature, patient management; KG: pathology

protocol presentation, review of literature, editing and final approval

of manuscript; AR: laboratory investigations, review of literature,

editing and final approval of manuscript.

Discussants: Clinical discussant and Pediatrician

1: Devika Laishram; Senior resident of treating unit: Ankur Kumar Jindal;

Pathologist 1: Poojitha Reddy; Pathologist 2: Kirti Gupta; Pediatrician

2: Amit Rawat; Pediatrician 3: Surjit Singh.

Funding: None; Competing interest: None

stated.

References

1. Marciano BE, Huang C-Y, Joshi G, Rezaei N,

Carvalho BC, Allwood Z, et al. BCG vaccination in patients with

severe combined immunodeficiency: Complications, risks, and vaccination

policies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1134-41.

2. Venaille A, Viola S, Peycelon M, Grand d’Esnon A,

Fasola S, Audry G, et al. [Recurrent small-bowel intussusceptions

revealing a disseminated BCG infection related to severe combined

immunodeficiency]. Arch Pediatr. 2014;21: 879-81.

3. Kwan A, Abraham RS, Currier R, Brower A,

Andruszewski K, Abbott JK, et al. Newborn screening for severe

combined immunodeficiency in 11 screening programs in the United States.

JAMA. 2014;312:729-38.

4. Rivers L, Gaspar HB. Severe combined

immunodeficiency: recent developments and guidance on clinical

management. Arch Dis Child. 2015;100:667-72.

5. Chinn IK, Shearer WT. Severe combined

immunodeficiency Disorders. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am.

2015;35:671-94.

6. Cirillo E, Giardino G, Gallo V, D’Assante R,

Grasso F, Romano R, et al. Severe combined immunodeficiency—an

update. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2015;1356:90-106.

7. Szczawińska-Popłonyk A, Jończyk-Potoczna K,

Ossowska L, Bręborowicz A, Bartkowska-Śniatkowska A, Wachowiak J.

Cytomegalovirus pneumonia as the first manifestation of severe combined

immunodeficiency. Cent-Eur J Immunol. 2014;39:392-5.

8. Notarangelo L. Primary immunodeficiencies. In:

Male D, Brostoff J, Roth DB, Roitt IM, editors. Immunology. 8th ed.

Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2013. p. 263-4.

9. Nickels AS, Boyce T, Joshi A, Hagan J. Absence of

the thymic shadow in a neonate suspected of primary immunodeficiency:

Not a straightforward clinical sign of immunodeficiency. J Pediatr.

2015;166:203.

10. Gupta K, Rawat A, Agrawal P, Jindal A, Nada R,

Saikia B, et al. Infectious and non-infectious complications in

primary immunodeficiency disorders: An autopsy study from North India. J

Clin Pathol. 2018;71:425-35.

11. Nezelof C. Thymic pathology in primary and

secondary immunodeficiencies. Histopathology. 1992;21:499-511.

12. Pang LC. Intussusception revisited:

Clinicopathologic analysis of 261 cases, with emphasis on pathogenesis.

South Med J. 1989;82:215-28.

|

|

|

|

|