|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2018;55:671-674 |

|

Encephalitic

presentation of Neonatal Chikungunya: A Case Series

|

|

Arti Maria 1,

Nagaratana Vallamkonda1,

Amlin Shukla1,

Aditya Bhatt1 and

Namrita Sachdev2

From Departments of 1Neonatology and

2Radiology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and

Research and Dr RML Hospital, New Delhi, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Arti Maria, Professor and Head,

Department of Neonatology, PGIMER and Dr RML Hospital, New Delhi 110

001, India.

Received: August 06, 2017;

Initial Review: January 01, 2018;

Accepted: May 28, 2018.

|

Objective: To describe clinical features and early neurological

outcomes in neonatal Chikungunya. Methods: Clinical, pathological

and radiological details of neonates with acute encephalitic features

and typical rash, later diagnosed as Chikungunya, are presented.

Neurodevelopmental evaluation and imaging was done at discharge/three

months. Results: Abnormal neurological examination with fever was

typical presentation in all 13 babies with/without seizures/peri-oral

rashes; 12 had persistent neurological abnormalities at discharge. A

follow-up at three months revealed continued neurodevelopmental

deficits. Neuroimaging abnormalities were seen in eight out of ten

cases. Conclusions: Perinatal Chikungunya should be considered in

neonates presenting within first week with fever, encephalopathy and

perioral rashes with/without seizures with history of maternal

Chikungunya within last week before delivery.

Keywords: Acute encephalitis syndrome; Meningoencephalitis;

Neonate; Rash.

|

|

C

hikungunya infection has seen a re-emergence in

India [1]. Typically described as a disease of adult and pediatric

population presenting with fever, arthralgia, arthritis, rash and

constitutional symptoms [2]. It is rarely considered as a diagnosis in

neonates, with little knowledge about natural history and clinical

features. Neurotropism of Chikungunya is under-reported even in adults

and children, and much rarely been described in neonates [3]. We

describe clinical and laboratory features of neonates presenting with

acute encephalitis syndrome and later diagnosed as Chikungunya

infection.

Methods

The medical record review was conducted in the

neonatal intensive care unit of a tertiary-care center in Delhi. Babies

who presented with neonatal sepsis like features (fever, lethargy, poor

suck, feed intolerance, respiratory distress, jaundice, skin rash,

seizures, shock, DIC etc.) but not supported by laboratory workup

for bacterial sepsis/meningitis were worked up for Chikungunya in view

of outbreak in the city (especially, in those with history of maternal

fever). NIV CHIK IgM Capture Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

(version 3, 4) was done in serum samples after obtaining consent from

parents. CSF Reverse Transcriptase Polymerase Chain reaction (RT-PCR)

was done from a reference laboratory. A large number of cases in a short

period prompted us to plan their detailed neuro-developmental follow-up,

and information about clinical features and laboratory investigations

was compiled retrospectively from case records. Neurosonogram and MRI

brain were done. Neurological examination was done using Hammersmith

neonatal examination tool at discharge/at three months of age.

A congenital Chickungunya case was defined as a baby

born to mother with high grade fever within seven days before delivery

with IgM seropositivity or CSF-positivity at time of neonatal diagnosis,

or a symptomatic baby in first seven days of life having a positive IgM

ELISA/RT-PCR in serum/CSF and negative bacterio-logical cultures. Any

seropositivity or CSF-positivity found in a symptomatic baby not

associated with maternal infection was defined as acquired Chikungunya.

Results

Ninety nine babies were admitted between August and

November, 2016, out of which 13 (11 males) were confirmed as Chikungunya.

10 cases were congenital, two acquired. One baby was adopted and

maternal clinical and laboratory status were not known. Encephalopathy

was present in all with duration varying from 10-15 days; 11 presented

with fever and six presented with seizures (Table I). Ten

cases had a characteristic acrofacial hyperpigmentation beginning three

to four days after fever in peri-oral region leading to characteristic

‘brownie-nose pigmentation’ (Fig. 1), later spreading to

trunk and limbs in patchy fashion. Shock was present in two cases but

was successfully treated and no death occurred. Hammersmith neonatal

examination showed hypotonia in 12 out of 13 infants at discharge;

visual and auditory development was normal in all 13 babies.

TABLE I Clinical and Laboratory Features of Neonates with Chikunguniya (N=13) [4]

|

Clinical features |

n |

|

Symptoms |

|

|

Lethargy |

13

|

|

Fever |

11

|

|

Feed refusal |

13

|

|

Convulsions |

6

|

|

Hyperpigmentation |

10

|

|

Hypotonia |

13

|

|

Investigations

|

|

|

Leucopenia <6000/cumm |

3 |

|

Thrombocytopenia <50,000/µL |

12

|

|

CRP >1 mg% |

6

|

|

Positive serum IgM (cases) |

13 |

|

Positive serum IgM (Mother) |

10

|

|

USG Cranium at discharge |

13 normal

|

|

USG Cranium at 3 months, n=2 |

2 abnormal

|

|

MRI at 3 months, n=10 |

8 abnormal

|

|

OAE, n=12 |

12 normal |

|

Cerebrospinal fluid Parameters |

|

|

Hypoglycorrhachia (<45 mg%) |

9 |

|

Increased protein (>80 mg%) |

9 |

|

Pleocytosis (>15 cells/mm3) |

2 |

|

Sterile culture |

13 |

|

CRP=C-reactive protein, USG=ultrasonography; MRI=Magnetic

resonance imaging; OAE=Otoacoustic emission. |

|

|

Fig. 1 Acro-facial cutaneous

hyperpigmentation.

|

Neuro-developmental assessment at three months

demonstrated four children with delayed milestones, out of which two

cases each had hypotonia and hypertonia. Seven cases had normal tone and

achieved normal milestones. Hyperpigmentation disappeared in all babies.

One baby showed additional flexion deformity in bilateral thumbs and

right middle finger at one month, which resolved by three months with

the help of physiotherapy. Two babies were lost to follow-up.

CSF-RT-PCR could only be done in one neonate which

was positive. CSF culture was sterile in all cases with cytology typical

of viral meningoencephalitis. CSF was completely normal in one baby.

Thrombocytopenia was present in 12 babies but none had clinical bleeding

(Table I).

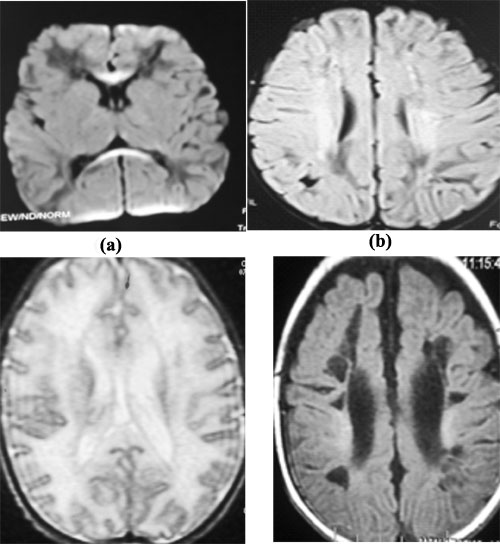

MRI brain had evidence of white matter

hyperintensities on T2 and FLAIR images involving frontal and parietal

lobes in bilateral peri-ventricular and subcortical region with evidence

of diffusion restriction in rostrum and splenium of corpus callosum in

three patients. No post-contrast enhancement/hemorrhage or infra-tentorial/cerebellar

involvement was seen.

Follow up MRI scan after three months revealed cystic

encephalomalacia and ventricular dilatation in two cases, and diffuse

cerebral atrophy in one (Fig. 2). Oto-acoustic emissions

(OAE) screening was normal in 12 babies and abnormal in one at

discharge, which normalized at three months.

|

| (c) |

(d) |

| |

Discussion

A major finding in this study was that neonatal

Chikungunya was quite common during the outbreak. Congenital infection

was more frequent than acquired. A striking clinical feature was

neurotropism, which was evident in all cases in form of refusal to feed,

lethargy and seizures. Another common clinical finding was

hyperpigmentation following a typical pattern. Laboratory features were

conspicuous by thrombo-cytopenia and positive serum IgM Chikungunya.

Initial USG cranium was normal in all cases but follow-up MRI scans were

abnormal in majority, along with developmental delay in these cases.

The study had a few limitations as information was

collected retrospectively and all cases were from referral unit which

could have resulted in bias. No statistical tests could be performed due

to small number of patients.

In our study, more male infants were admitted with

the infection, similar to another Indian study [5]. Most cases were

prenatally acquired similar to a data from the French Reunion islands

[6]. In contract to the predominant encephalopathic presentation in this

study, a Latin American study [7] showed only a 7.1% incidence of

meningoencephalitis in newborns. However, review of their study shows

that 98-100% babies presented with irritability and refusal to feed,

which may suggest presence of encephalopathy. The cohort in this study

was from intramural deliveries while ours were referred babies.

A higher incidence of encephalitis in neonates with

Chikungunya could be attributed to greater viral replication and delayed

clearance in infants [8]. Ineffective interferon-1 activation has been

demonstrated in mice to be associated with severe disease. Neurological

spread occurs through areas in brain poorly protected by blood brain

barrier [9]. The plausible mechanisms of neuronal damage are: invasion

of choroid plexus and leptomeninges leading to defective neuronal

migration. Another possibility could be microglial activation [10]. The

study on mice also demonstrated that the vertical transmission of the

virus is Peri-partum and not ante-partum [9].

Similar radiologic and developmental findings were

noticed in a cohort study from Reunion Island [10]. Peri-oral hyper

pigmentation fever, leukopenia and mild thrombocytopenia were a

predominant feature in our study, similar to another study [5],

post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation could be due to virus-triggered

increased intra-epidermal dispersion/retention of melanin [11]. Fixed

flexion deformity in bilateral thumb reported in one of our babies is

similar to another case-report [12].

Our study shows that Chikungunya should be considered

as a differential diagnosis in neonates presenting with fever, typical

hyperpigmentation and encephalopathy especially during outbreaks. Cases

with perinatal infection are prone to developmental delay and require

long term neuro-developmental follow-up.

Acknowledgements: Dr Anthony Costello for editing

the manuscript and Dr Rakesh Dey for helping in data collection.

Contributors: AM: conceptualized and

designed the study and revised it critically; NV: acquisition of

data, initial analysis, and reviewed and revised manuscript; AS:

analysis and interpreted blood and CSF findings, and critically reviewed

the manuscript; AB: drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed

the manuscript; NS: Analysis and interpretation of Radiological

findings and reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final

manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of work.

Funding: None; Competing interests: None

stated.

|

What This Study Adds?

•

Neonatal Chikungunya should be

considered in neonates presenting with fever, encephalopathy and

cutaneous hyperpigmentation with/without seizures.

•

Confirmed cases need a detailed neurodevelopmental

follow-up.

|

References

1. Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry

of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. National Vector Borne

Disease Control Programme. Available from:

http://nvbdcp.gov.in/chik-cd.html. Accessed January 28, 2018.

2. Da Cunha RV, Trinta KS. Chikungunya virus:

Clinical aspects and treatment - A review. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz.

2017;112:523-31.

3. Chandak NH, Kashyap RS, Kabra D, Karandikar P,

Saha SS, Morey SH, et al. Neurological complications of

Chikungunya virus infection. Neurol India. 2009;57:177-80.

4. MacDonald MG, Seshia MMK. Avery’s Neonatology:

Pathophysiology and Management of the Newborn. 7th ed; 2015. p.

967.

5. Valamparampil JJ, Chirakkarot S, Letha S,

Jayakumar C, Gopinathan KM. Clinical profile of Chikungunya in infants.

Indian J Pediatr. 2009;76:151-5.

6. Lenglet Y, Barau G, Robillard PY, Randrianaivo H,

Michault A, Bouveret A, et al. Chikungunya infection in

pregnancy: Evidence for intrauterine infection in pregnant women and

vertical transmission in the parturient. Survey of the Reunion Island

outbreak. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2006;35:578-83.

7. Torres JR, Falleiros-Arlant LH, Duenas L,

Pleitez-Navarrete J, Salgado DM, Castillo JB. Congenital and perinatal

complications of chikungunya fever: A Latin American experience. Int J

Infect Dis. 2016 Oct;51:85-8.

8. Mohanty I, Dash M, Sahu S, Narasimham MV, Panda P,

Padhi S. Seroprevalence of chikungunya in Southern Odisha. J Family Med

Prim Care. 2013;2:33-6.

9. Couderc T, Chretien F, Schilte C, Disson O,

Brigitte M, Guivel-Benhassine F, et al. A mouse model for

Chikungunya: Young age and inefficient type-I interferon signaling are

risk factors for severe disease. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e29.

10. Gerardin P, Samperiz S, Ramful D, Boumahni B,

Bintner M, Alessandri JL, et al. Neurocognitive outcome of

children exposed to perinatal mother-to-child Chikungunya virus

infection: The CHIMERE cohort study on Reunion Island. PLoS Negl Trop

Dis. 2014;8:e2996.

11. Seetharam KA, Sridevi K, Vidyasagar P. Cutaneous

manifestations of chikungunya fever. Indian Pediatr. 2012;49:51-3.

12. Gopakumar H, Ramachandran S. Congenital

chikungunya. J Clin Neonatol. 2012;1:155-6.

|

|

|

|

|