|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2017;54: 652-660 |

|

Consensus Guidelines on Evaluation and

Management of the Febrile Child Presenting to the Emergency

Department in India

|

|

*Prashant Mahajan,

#Prerna Batra,

$Neha Thakur,

‡Reena Patel, ^Narendra

Rai, £Nitin

Trivedi, @Bernhard

Fassl, **Binita Shah, ##Marie

Lozon, $$Rockerfeller

A Oteng, ‡‡Abhijeet

Saha, #Dheeraj

Shah and @@Sagar

Galwankar;

for Academic College of Emergency

Experts in India (ACEE-INDIA) – INDO US Emergency and Trauma

Collaborative

From *Departments of Emergency Medicine and

Pediatrics, University of Michigan (Ann Arbor, MI, USA); #Department

of Pediatrics, University College of Medical Sciences and Guru Teg

Bahadur Hospital, Delhi, India; $Department of Pediatrics,

Hind Institute of Medical Sciences, Lucknow, India; ‡Department

of Pediatrics, Division of Inpatient Medicine, University of Utah, (Salt

Lake City, UT, USA); ^Department of Pediatrics, Hind

Institute of Medical Sciences, Lucknow, India; £Department of

Pediatrics, Mahatma Gandhi Medical College and Hospital, Jaipur, India;

@Department of Pediatrics; Division of Inpatient Medicine and

Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of Utah, (Salt

Lake City, UT, USA); **Departments of Emergency Medicine and Pediatrics,

SUNY Downstate Medical Center, Kings County Hospital Center (Brooklyn,

NY, USA); ##Department of Emergency Medicine, University of

Michigan, (Ann Arbor, MI, USA); $$Department of Emergency

Medicine, University of Michigan (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and Directorate of

Emergency Medicine, KomfoAnokye Teaching Hospital (Kumasi, Ghana); ‘‡‡Department

of Pediatrics, Lady Hardinge Medical College, New Delhi, India; and

@@ Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Florida,

(Jacksonville, FL, USA).

Correspondence to: Dr Prashant Mahajan,

CS Mott Children’s Hospital, University of Michigan 1540 East Hospital

drive, Room 2-737, SPC 4260, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-4260, USA.

Email: [email protected]

Received: October 11, 2016;

Initial Review: January 11, 2017;

Accepted: May 25, 2017.

Published online: June 04, 2017.

PII:S097475591600069

|

|

Justification: India, home to

almost 1.5 billion people, is in need of a country-specific,

evidence-based, consensus approach for the emergency department (ED)

evaluation and management of the febrile child.

Process: We held two consensus

meetings, performed an exhaustive literature review, and held ongoing

web-based discussions to arrive at a formal consensus on the proposed

evaluation and management algorithm. The first meeting was held in Delhi

in October 2015, under the auspices of Pediatric Emergency Medicine

(PEM) Section of Academic College of Emergency Experts in India

(ACEE-INDIA); and the second meeting was conducted at Pune during

Emergency Medical Pediatrics and Recent Trends (EMPART 2016) in March

2016. The second meeting was followed with futher e-mail-based

discussions to arrive at a formal consensus on the proposed algorithm.

Objective: To develop an

algorithmic approach for the evaluation and management of the febrile

child that can be easily applied in the context of emergency care and

modified based on local epidemiology and practice standards.

Recommendations: We created an

algorithm that can assist the clinician in the evaluation and management

of the febrile child presenting to the ED, contextualized to health care

in India. This guideline includes the following key components: triage

and the timely assessment; evaluation; and patient disposition from the

ED. We urge the development and creation of a robust data repository of

minimal standard data elements. This would provide a systematic

measurement of the care processes and patient outcomes, and a better

understanding of various etiologies of febrile illnesses in India; both

of which can be used to further modify the proposed approach and

algorithm.

Keywords: Consensus statement, Diagnosis,

Fever, Infection, Sepsis.

|

|

A

ll over the world, fever in children is one of

the most common reasons for parents to seek medical care. It is

estimated that approximately 20% of all pediatric emergency department

(ED) visits in the United States (US) are for evaluation of fever [1].

In recent decades, an extensive amount of literature and evidence has

led to a consensus approach to the evaluation and management of febrile

children; which has evolved secondary to its changing epidemiology. The

change in epidemiology of the febrile child is the result of the

substantial impact of conjugate vaccines against capsulated bacterial

pathogens including H. influenzae and S. pneumoniae

[1].

To reduce variation, multiple guidelines have been

proposed including those from academic societies such as the American

Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and American College of Emergency Physicians

(ACEP) [2]. Despite some differences, most guidelines advocate a

comprehensive evaluation of the very young febrile infant (28 days and

younger) and a less conservative approach for older infants. Febrile

infants undergo invasive procedures such as lumbar puncture, complete

blood counts and urinalysis. Most febrile infants, especially those less

than 28 days of age, are routinely hospitalized and treated empirically

with broad spectrum antibiotics such as third generation cephalosporins

along with ampicillin.

There continues to be practice variation also, when

applying evidence and consensus-based guidelines [3-5]. Depending upon

clinician suspicion, clinicians may evaluate for etiologies as variable

as bacterial pneumonia and bacterial enteritis. Currently available

"standardized" approaches, regardless of practice variation, remain

problematic for various reasons: (i) prediction rules and/or

guidelines have not been validated across cultural, geographic,

socio-economic environments and may not be applicable in all clinical

settings; (ii) the epidemiology of pathogens causing Serious

Bacterial Infection (SBI) has changed due to the impact of conjugate

vaccines; (iii) clinicians are not confident about the test

characteristics of various screening tools, especially the

discriminatory abilities of the complete blood counts, and finally; (iv)

newer screening tools such as procalcitonin have not been studied or

integrated into clinical decision making in a robust manner.

Evaluation and management of the febrile child in

India: Children may present with fever as an initial/isolated

symptom of a yet undifferentiated illness or with localizing signs that

suggest an etiology such as pneumonia. A majority of children with fever

without localizing signs will have a viral etiology which does not

warrant laboratory evaluation and can often be managed with instructions

for ensuring adequate hydration and use of antipyretics [6]. In one

study it is estimated that up to 10% of febrile children, especially

those 3 months of age and younger will have bacterial illnesses in the

form of occult bacteremia, septicemia, bacterial meningitis, pneumonia,

UTI, bacterial gastroenteritis, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, and

other general endemic tropical diseases [7]. However, etiologies of

fever in the Indian ED context could vary from benign viral illnesses,

commonly reported in US and Europe (e.g. respiratory syncytial

virus (RSV), Enterovirus infections) to illnesses by organisms uncommon

in industrialized countries: bacteria (e.g. S. typhi),

viruses (e.g. measles, dengue, chikungunya) and parasites

(e.g. malaria, kala azar) as well as endemic illness outbreaks

due to meningococci and leptospira.

India is a tropical country with a distinct spectrum

of common tropical illnesses particularly seen in post-monsoon season

such as dengue, rickettsial infections, scrub typhus, malaria (usually

due to Plasmodium falciparum), typhoid and leptospirosis [8]. Thus, the

algorithmic approach utilized in the US and Europe is not applicable in

Indian EDs, especially when evaluating a child with fever without

source.

Emergency medicine is a growing medical specialty as

evidenced by the rising number of publications appearing in the

peer-reviewed literature demonstrating its growth and influence on

healthcare delivery in India [9]. In conjunction with emergency

medicine, as well as independently, pediatric emergency medicine is

rapidly evolving as a sub-specialty and efforts are underway for its

formal specialty status recognition [10]. Development of a consensus

statement that is relevant to the epidemiology of illness in the Indian

context will help reduce practice pattern variation, optimize resource

allocation as well as education, training and decision-making by both

policy makers and health care administrators in the federal, public and

private sectors.Moreover, evaluation and management of the febrile

child, continues to remain a clinical challenge in the Indian ED context

and the development of a consensus based practice guideline will serve

as a valuable resource.

Process

We held two consensus meetings of Pediatric Emergency

Medicine (PEM) Section of Academic College of Emergency Experts in India

(ACEE-INDIA) in Delhi (October 2015) and in Pune (March 2016). An

exhaustive literature review was performed and ongoing web-based

discussions were held to arrive at a consensus on the proposed

evaluation and management of febrile infants and children. We provide a

pragmatic and simple to use algorithm that will assist, but not

replace, clinician decision making for the ED evaluation and management

of the febrile child.

We have identified the key concerns regarding a

standardized approach to the evaluation and care of the febrile child in

an ED in India (Box 1).

|

BOX 1 Key Concerns in Case of the Febrile

Child in an Indian Emergency Department

• Epidemiology of the febrile child in India

is different from that of the Western Countries; published

guidelines will require further modification for them to be

applicable to the Indian ED context.

• The ill-appearing febrile child will need a

separate approach with the goal of early recognition of

impending cardiovascular and respiratory compromise regardless

of underlying etiology.

• Other aspects such as ongoing epidemics (e.g.,

dengue) or co-existing co-morbid conditions (e.g.,

malnutrition) should be part of the approach.

• There is no wide-spread, comprehensive data

available to systematically report the epidemiology of febrile

illnesses that present to the EDs across the country.

• Approach considerations for

resource-replete vs. resource-constrained settings is

important. Consensus among experts was that with respect to

medical interventions, clinical practice guidelines should

ideally be applicable in all settings.

|

Literature Review: Following the initial

consensus meeting, an exhaustive review of available literature

pertaining to each component was identified. We used structured queries

including terms such as fever, febrile child, febrile infant, fever

without source, serious bacterial infection, bacteremia, to search

databases including Pubmed, Google scholar to develop a comprehensive

database of peer reviewed literature in an Endnote file. These

manuscripts along with textbook chapters on the febrile child in

commonly accepted textbooks of pediatrics and pediatric emergency

medicine were reviewed. The literature review included topics unique to

the India based ED setting: fever in immunocompromised and/or severely

malnourished children, fever with localization, fever without

localization and etiologies specific to our country like malaria,

dengue, and enteric infections. A drafting committee was selected to

synthesize the literature and key concerns outlined at the initial

in-person meeting. Drafts were circulated electronically to engage and

further solicit input. This process resulted in specific evaluation and

management recommendations for each condition.

Recommendations

Considering the available literature and the needs

identified by the expert panel, we created an algorithm for the

evaluation and management for a febrile child presenting to the ED

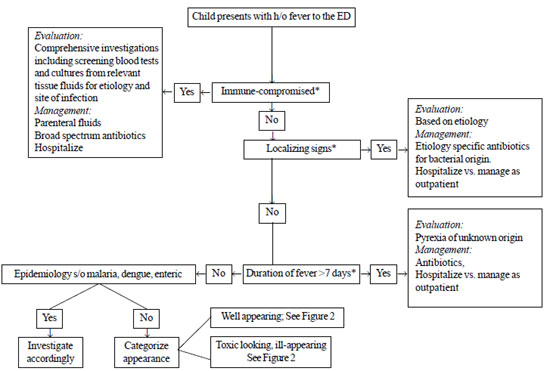

within the context of healthcare in India (Fig. 1).

This algorithmic approach incorporated the following: localizing

symptoms, epidemiologic evidence, physiologic state (i.e.

immunocompromised or not; well appearing or ill appearing), duration of

fever, and age of the child. For the purposes of algorithm application,

we have outlined terms, definitions and categories below.

*Child could be ill or well appearing – please see Fig. 2 for

further management of ill- and well-appearing Child.

|

|

Fig. 1 Algorithm for evaluation and

management for the febrile child presenting to Emergency

department within the context ot health care in India.

|

Definition of fever: Fever is defined as a

rectal temperature ³38.0ºC

or ³100.4ºF

[1,11]. Axillary temperature is 0.3-0.6ºC

lower than the rectal temperature. Patients often present to the ED with

subjective fever at home, felt by tactile assessment only. In this

scenario, we suggest that clinicians obtain a detailed history including

association with lethargy, perspiration, irritability or other

concerning symptoms for ascertainment of clinically relevant fever and

before providing a disposition.

Method of temperature assessment: Axillary

thermometry is the most widely used method in clinical practice;

however, axillary thermometers are not reliable with regards to

measuring body temperature in infants and children [12]. Rectal

temperature was identified as the most accurate measurement as it is

closest to the core body temperature [1,13] and is the preferred method

of temperature determination in very young children. Temporal artery and

tympanic membrane thermometers can be used for quick assessment of

temperature [14], provided the clinician is aware of the limitations and

performance characteristics of each method. Further, based on the

clinical situation, one must confirm the core temperature by the rectal

route. No definite cut-offs have been given for defining fever using

tympanic and temporal thermometers.

Triage: A prompt and rapid clinical assessment by

trained providers should be performed at triage [15,16]. Vital signs

(temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, and pulse

oximetry) measurement along with the use of pediatric assessment

triangle and/or Pediatric Early Warning Scores (PEWS) to quantify

severity of illness is highly recommended to help categorize the febrile

child as well- appearing or ill- appearing [17]. Providers (health

workers, nurses and physicians) should be trained in performance of

these assessments reliably and perform them in a timely manner. All

febrile children who appear to be at risk for cardio-pulmonary

compromise and septic shock should have life-saving resuscitative

procedures performed regardless of etiology of fever. These include

obtaining vascular access (either intravenous or intraosseous), managing

the airway with provision of oxygenation and placing the child on a

cardiac monitor. If such resources are available, a bedside glucose test

along with a capillary blood gas, point-of-care serum electrolytes,

ionized calcium and lactate levels should be performed to guide

resuscitation. Provision of broad-spectrum antibiotics to treat

suspected bacterial pathogens should also be provided as rapidly as

possible. If patient is in shock, management with rapid and adequate

amounts of isotonic fluids should be initiated. Table I

summarizes the identification and immediate management of emergent

patients. Immediate treatment steps should be initiated by healthcare

personnel and often can be initiated at triage.

TABLE I Identification and Immediate Management of Emergent/Life-Threatening Conditions

|

Symptoms/Signs |

Immediate treatment |

After stabilization

|

|

Airway and breathing |

|

•Airway obstruction |

1.Secure and clear airway

|

1.Blood glucose – correct immediately with D25 2cc/kg |

|

•Cyanosis |

2.Provide bag and mask ventilation |

|

|

•Respiratory distress |

3.Intubate if ongoing respiratory support is needed.

|

2.Hemogram |

|

•Respiratory failure Circulation |

4.Give oxygen:Nasal Cannula 2-3 LPM or Face Mask 5 LPM |

3.Blood gas

|

| |

|

4.Electrolytes

|

|

•Heart rate |

1.Establish intravenous (IV) or intraosseous line (IO) line |

5.Peripheral smear for malaria parasites if indicated |

|

•Capillary refill time |

2.Give isotonic fluid bolus if clinically indicated |

|

|

•Pulses(bounding or weak) |

3.Continued assessment for signs of shock and cardiovascular

compromise |

6.Specific investigatons as |

|

•Blood pressure |

|

indicated for instance blood

|

|

•Urine output

|

|

group type and cross match,

|

|

•Level of consciousness |

|

toxicologic screens in blood and

|

|

CNS |

|

urine. |

|

•Unconscious or convulsions |

|

|

Evaluation of the febrile child: After

initial stabilization, patient’s evaluation and management should be

done as per the algorithm described in Fig. 1.

Immunocompromised Children

Immune-compromised children are at high risk of

serious infections, with grave prognosis. Thus, it becomes important to

identify this group in ED at triage itself and have an aggressive

approach. Children with neutropenia, with malignancy on chemotherapy,

those on long term oral steroids like nephrotic syndrome, with human

immunodeficiency virus (HIV infection), and with primary

immunodeficiency states are the children at high risk and need extensive

evaluation in febrile state [18]. Fever in a neutropenic patient is

always an emergency, regardless of triage status and should be

categorized as a life-threatening event (E).

Fever With Focus or Localization

When a child presents to ED with fever and a

localizing symptom/sign, specific management becomes easier. Some of the

common localizing signs are seizures, cough, ear discharge, loose

stools, dysuria and rashes. History and evaluation in the ED to

determine the focus should be done after triage and initial

stabilization. Management depends upon the common organisms that prevail

in that particular age group. Many of these infections have viral

etiologies, which need only supportive treatment and a follow up.

Emerging antimicrobial resistance is a global health problem and

rational use of antibiotics in ED will go a long way in ameliorating

this issue.

Fever Without Localization

In a tropical country like India, it is not uncommon

to have febrile children without any localization, with epidemiological

evidence suggestive of a particular infectious etiology. These include

conditions like malaria, dengue, and enteric fever. Due to the

overlapping clinical presentation, it becomes difficult to pin point the

diagnosis in ED itself. Such children should be investigated for the

conditions with high index of suspicion and supportive therapy should be

provided.

|

| |

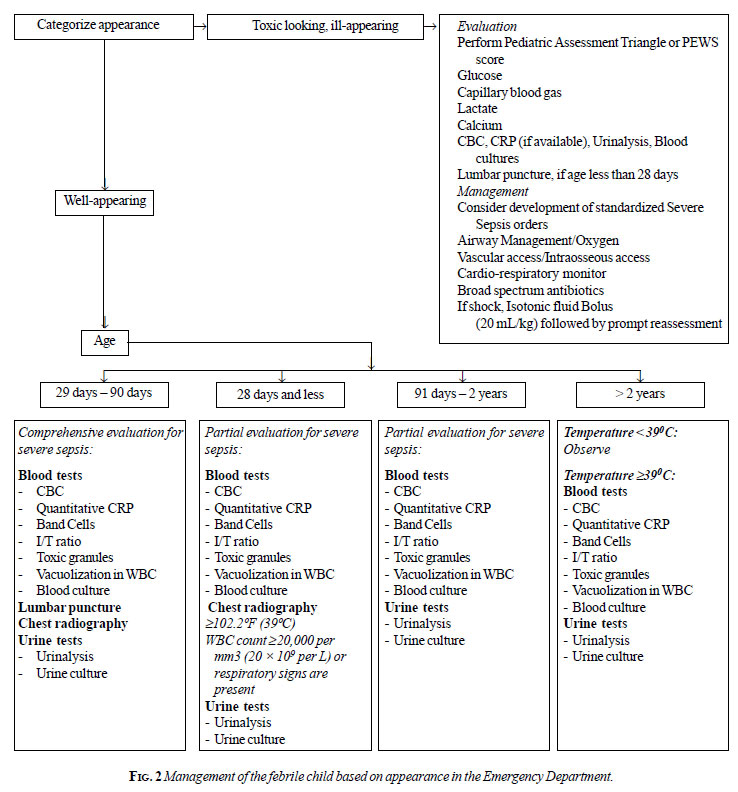

Fever without localization is a short duration

febrile illness of 5 to 7 days without an identifiable cause after

performance of history and examination [19-21]. ACEE recommends child to

be categorized into well- or ill-/toxic-appearing. Emergent

hospitalization and comprehensive evaluation is recommended in such a

child at any age (Fig. 2). Further, evaluation and

management of a well-looking child is based on the defined age groups

i.e., neonates (28 days and less), young infant (29-90 days); older

infant and young children (91 days – 2 years), and children more than 2

years (Fig. 2). There is no consensus among experts

regarding optimal cut-offs for evaluation of fever without focus. Most

have either used anecdotal or observational data as well as empiric data

to arrive at cut-offs. Furthermore, the physiologic rationale is often

missing. We chose the cut-offs as listed below:

28 days and less – most algorithms use this as a

cut-off and is a category of the febrile infants that probably has the

most consensus in the evaluation and management.

29-90 day cut-off – because this age group has

probably been the least studied as well has the most variation with

regards to a comprehensive evaluation, especially with relation to

performance of lumbar punctures. In addition, this is also the age

cut-off that is used in some febrile infant management algorithms.

91 days to 2 years – this is because most

febrile infants beyond 90 days will have a positive impact of

vaccinations as well as have a clinical examination that will allow the

clinician to selectively evaluate for fever instead of a comprehensive

evaluation that includes blood, urine and CSF studies. Specifically, the

consensus chose to limit the upper age to 2 years because UTI risk drops

substantially after the age of 2 years in female children.

These cut-offs are provided as a guide and also as a

basis to collect data in the Indian context. As more evidence is

generated, these may be modified further.

Evaluation

Evaluation should include a complete history and

physical examination. In a tropical country like India, dehydration

fever may be seen in newborns and young infants. Vaccination history

could avoid unnecessary investigation. Signs like irritability; poor

feeding, poor activity, and child not appearing well are subtle markers

for serious underlying illness [22]. Pulse rate and volume, pulse

oximetry, temperature, capillary refill time, respiratory rate (RR) and

type should be documented. A complete head to toe exam with all clothes

removed will help to find an occult cause of fever.

Newborns (< 28 days): All newborns

with fever should be admitted. A complete investigative workup which

includes complete blood count (CBC), C- reactive protein (CRP),

peripheral blood smear (PBS) (band form, toxic granules, vacuolization,

immature/total ratio ), blood and urine culture, urine analysis (UA),

lumbar puncture (LP), and chest X- ray (CXR) is mandatory. Stool

should be examined for pus cell and red blood cell (RBC) only if change

in frequency of stool is present. First negative septic screen in an

active febrile newborn is not the indication for discharge.

Young infants (29 to 90 days): Active

young infant between 29-90 days of age with fever should be observed in

the ED with vital sign measurement. Complete blood count (CBC),

peripheral blood smear (PBS), urine analysis (UA), and blood and urine

culture is necessary. Chest radiography is indicated if temperature

³102.2ºF

(39°C), leucocyte count ³20,000

per mm3 or respiratory signs

are present [23]. Urine tests recommended are microscopy and culture

from urine obtained by catheterization.

91 days to 2 years: In some instances, lumbar

puncture may be deferred in this age group. Investigative workup which

include complete blood count (CBC), C-reactive protein (CRP), peripheral

blood smear (PBS) (band form, toxic granules, vacuolization,

immature/total ratio), blood and urine culture, and urinanalysis.

Children above 2 years: If temperature <39ºC,

only obser-vation is recommended. If temperature is 39ºC or more,

investigative workup, which includes CBC, CRP, PBS (band form, toxic

granules, vacuolization, immature / total ratio), blood and urine

culture, Urinanalysis needs to be done [23]. PBS and rapid tests for

malaria, dengue and enteric may be done in endemic areas. Blood culture

may be taken in typhoid-endemic areas.

Sepsis screen parameters and serious bacterial

infection

Various sepsis screen parameters have been used with

different permutations and combinations to rule in and rule out SBI.

Markic, et al. [24] observed CBC, PCT, CRP and lab score

³3 as useful markers

for serious bacterial infections. Sensitivity and specificity was better

in age group of £90

days when compared with age group of

£180 days. In another

large study, both CRP (area under the receiver operating curve - ROC

0.77, 95% CI 0.69-0.85) and PCT (ROC area 0.75, CI 0.67-0.83) were found

to be strong predictors of serious bacterial infection[24]. Absolute

band cells and PCT were reported as the best markers of SBI in children

less than 36 months of age in another study, with PCT having the largest

ROC (0.80, 95% CI 0.71-0.89) [25, 26]. The high cost and limited

availability of PCT preclude its use as a screening tool in Indian EDs.

Management

In ill-appearing neonates and young infants,

intravenous (IV) access should be established and empiric antibiotics

should be started in the ED. Up to 28 days of age, ampicillin 100 to 200

mg/kg/day divided 8 hourly and gentamicin 7.5 mg/kg/day divided 8 hourly

should be started, whereas in older infants, intravenous Ceftriaxone 100

mg/kg/day or 75 mg/kg/day divided 12 hourly is given, depending on

presence or absence of meningeal involvement.

|

BOX 2 Indications for Hospitalization and

Discharge from Emergency Department

Indications for

Hospitalization

• All emergency patients in

need for airway stabilization, ventilation or continued O2

requirement

• Age <28 days

• Prolonged seizure/status

epilepticus

• Altered sensorium

• Electrolyte imbalance

• Signs of Severe Dehydration

• Not feeding well

• Respiratory distress

• SPO2 <90% in room air

• Drug toxicity or drug

reaction

• Unknown or undetermined

cause

• Concern for non-compliance

or inability to follow-up

Indications for Discharge

• No emergent need for

airway, ventilation or circulatory support

• Vitals stable

• Child accepting

• Definitive management plan

has been worked out

• Compliance ensured

• Follow up ensured

|

Patient disposition from the ED: After

initial stabilization and management in the ED, the patient may either

be hospitalized or be discharged home. Box 2 gives

indications for hospitalization and discharge of a febrile child from

ED. Patiet’s stable condition, definite follow up plan and compliance

become important while discharging the patient home. Table II

provides broad guidelines for admission in pediatric floor or intensive

care unit (ICU).

TABLE II Patient Disposition Guidelines

|

Disposition |

Action |

|

Observation in ED |

Reassess patient frequently, review and document vital signs

hourly |

|

Discharging home |

Provide appropriate counseling and a follow-up plan. Elicit

understanding of care plan by caretakers |

|

Admission/Transfer to Pediatric Floor |

Hemodynamically and respiratory stable patient, needs ongoing

treatment, monitoring and workup; |

|

Transfer to ICU |

Patient remains in critical condition, warrants ongoing

cardiorespiratory support to sustain life |

|

ED: Emergency department; ICU: Intensive care unit. |

Some patients may need transfer to another health

facility, due to non-availability of appropriate resources or services.

Box 3 summarizes the guidelines for referral that should

be stringently followed.

|

BOX 3 Guiedelines for Transfer* to

Another Health Facility

• Transfer, only when it is

stable to transfer.

• Appropriate stabilization

before transportation:

• Secure airway

• Intravenous or intraosseous

access

• Place on cardiac monitor

• Discuss transfer options

with the patients’ primary caregiver if available. Transfer is

dependent upon patient’s current status, the clinical concerns

of the provider, the best place for receiving adequate care, and

if caregiver/family is willing to transfer.

• Directly communicate with

receiving hospital regarding that transfer is required.

• Transport with person(s),

capable of managing any emergency en-route.

*due to non-availability of appropriate

resources or services

|

Summary

The outlined algorithmic approach on management of

fever in the ED is the first step of its kind initiated by the PEM

Chapter of ACEE-India under the aegis of INDO-US Emergency and Trauma

Collaborative. This approach is based on the current literature search

and available evidence pertaining to Indian context, aiming to

familiarize the emergency physicians to a stepwise approach for

evaluation and management of fever. This approach also includes focused

triage and patient disposition guidelines. Further steps are intended

to:

• obtain input from experts in pediatrics, EM,

PEM, infectious diseases, epidemiologists to modify the algorithm

• create a robust database to collect

retrospective and prospective data to elucidate the epidemiology of

the febrile child across various settings.

• modify the algorithm based on epidemiological

evidence.

• implement the algorithm and monitor compliance

as well as measure impact on practice pattern variation, clinical

outcomes and resource burden.

This algorithmic approach will require ongoing,

periodic revision(s) as new research emerges and is established in the

field.

Acknowledgenent: Elizabeth Duffy, MA, Department

of Emergency Medicine, University of Michigan (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) for

helping in critical editing, reviewing and formatting of the manuscript.

Contributors: PM: Guarantor of the paper with

responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole; Substantial

contributions to the conception and design of the work, and drafted and

critically revised for important intellectual content; PB, RP, BF, BS,

SG: substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work,

and drafted and critically revised for important intellectual content;

Neha T, NR, Nitin T, AS, DS: substantial contributions to the

conception, and provided critical revisions; ML,RAO: Substantial

contributions to the design of the work, and critically revised content;

SG: Substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work;

and drafted and critically revised for important intellectual content.

All authors approved the final version to be published, and are

accountable for all aspects of the work to ensure that questions related

to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately

investigated and resolved.

Funding: None. Competing Interests: None

stated.

ANNEXURE I

Participants of the Consensus Meetings

I Consensus Meeting

Chairperson: Prashant Mahajan, (Michigan, USA);

Experts: Binita Shah (Brooklyn, NY, USA), Bernhard Fassl (UT,

USA), Prerna Batra, (Delhi, India), Abhijeet Saha (New Delhi, India),

Dheeraj Shah (Delhi, India), Indumathy Santhanam (Chennai, India), AP

Dubey (New Delhi, India), Devendra Mishra (New Delhi, India), Santosh

Soans (Bangalore, India), Reena Patel (UT, USA), Narendra Rai (Lucknow,

India), Neha Thakur (Lucknow, India), Nitin Trivedi (Jaipur, India).

II Consensus Meeting

Chairperson: Binita Shah (Brooklyn, NY, USA); Participants:

Prerna Batra (Delhi, India), Abhijeet Saha (Delhi, India), Reena Patel

(Salt Lake City, UT, USA), Neha Thakur (Lucknow, India), Nitin Trivedi (Jaipur,

India), and Narendra Rai (Lucknow, India).

References

1. Balmuth F, Henretig FM, Alpern ER. Fever. In:

RG Bachur& KN Shaw (eds.) Fleisher & Ludwig’s Textbook of Pediatric

Emergency Medicine, 7th edition. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

Philadelphia, PA, USA.2016. p. 176-85.

2. ACEP Clinical Policies Committee and Clinical

Policies Subcommittee on Pediatric Fever. Clinical Policy for Children

Younger than Three Years Presenting to the Emergency Department with

Fever. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42:530-45.

3. Seow VK, Lin AC, Lin IY, Chen CC, Chen KC, Wang

TL, et al. Comparing different patterns for managing febrile

children in the ED between emergency and pediatric physicians: impact on

patient outcome. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25:1004-8.

4. Phillips B, Selwood K, Lane SM, Skinner R, Gibson

F, Chisholm JC; United Kingdom Children’s Cancer Study Group. Variation

in policies for the management of febrile neutropenia in United Kingdom

Children’s Cancer Study Group centres. Arch Dis Child.2007;92:495-8.

5. Aronson PL, Thurm C, Williams DJ, Nigrovic LE,

Alpern ER, Tieder JS, et al.; Febrile Young Infant Research

Collaborative. Association of clinical practice guidelines with

emergency department management of febrile infants

£56 days of age. J

Hosp Med. 2015;10:358-65.

6. Harper MB. Update on the management of the febrile

infant. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. 2004;5:5-12.

7. Abrahamsen SK, Haugen CN, Rupali P, Mathai D,

Langeland N, Eide GE, et al. Fever in the tropics: Aetiology and

case-fatality-A prospective observational study in a tertiary care

hospital in South India. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:355.

8. Singhi S, Rungta N. Tropical fever: Management

Guidelines. Ind J Crit Care Medicine. 2014;18:62-9.

9. Jatana SK. Pediatric emergencies in office

practice—an overview. Med J Armed Forces India. 2012; 68:4-5.

10. Mahajan P, Batra P, Shah B, Saha A, Galwankar S,

Aggrawal P, et al. The 2015 Academic College of Emergency Experts

in India’s INDO-US Joint Working Group white paper on establishing an

academic department and training pediatric emergency medicine

specialists in India. Indian Pediatr. 2015;52:1061-71.

11. Niven DJ, Gaudet JE, Laupland KB, Mrklas KJ,

Roberts DJ, Stelfox HT. Accuracy of peripheral thermometers for

estimating temperature: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann

Intern Med. 2015;163:768-77.

12. Brown PJ, Christmas BF, Ford RP. Taking an

infant’s temperature: Axillary or rectal thermometer? N Z Med

J. 1992;105:309-11.

13. Batra P, Goyal S. Comparison of rectal, axillary,

tympanic, and temporal artery thermometry in the pediatric emergency

room. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013;29:63-6.

14. Batra P, Saha A, Faridi MM. Thermometry in

children. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2012;5:246-9.

15. Pocketbook of Hospital Care for Children:

Guidelines for the Management of Common Childhood Illnesses – Second

Edition. WHO 2013. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/81170/1/9789241548373_eng.pdf.

Accessed August 25, 2016.

16. WHO Emergency Triage and Treatment (ETAT). Manual

for Participants. WHO Press. Geneva, Switzerland. 2005. Available from:

http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43386/1/9241546875_eng.pdf.

Accessed August 25, 2016.

17. Seiger N1, Maconochie I, Oostenbrink R, Moll

HA.Validity of different pediatric early warning scores in the emergency

department. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e841-50.

18. Holtzclaw B J. Managing fever and febrile

symptoms in HIV: Evidence-based approaches. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care.

2013;24: S86-102.

19. Jhaveri R, Byington CL, Klein JO, Shapiro ED.

Management of the nontoxic-appearing acutely febrile child: a 21st

century approach. J Pediatr. 2011;159:181-5.

20. Brown L, Shaw T, Moynihan JA, Denmark TK, Mody A,

Wittlake WA. Investigation of afebrile neonates with a history of fever.

Canad J Emerg Med. 2004;6:343-8.

21. Ishimine P. Fever without source in children 0 to

36 months of age. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2006;53:167-94.

22. Care Process Model. Emergency Management of the

well-appearing febrile infant age 1-90 days. Intermountain Health Care.

May 2013. Available from: https://intermountain

healthcare.org/ext/Dcmnt%3Fncid%3D520441555. Accessed August 25,

2016.

23. Bressan S, Andreola B, Cattelan F, Zangardi T,

Perilongo G, Da Dalt L. Predicting severe bacterial infections in

well-appearing febrile neonates: laboratory markers accuracy and

duration of fever. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:227-32.

24. Markic J, Kovacevic T, Krzelj V, Bosnjak N,

Sapunar A. Lab-score is a valuable predictor of serious bacterial

infection in infants admitted to hospital.Wien Klin Wochenschr.

2015;127:942-7.

25. Nijman RG, Moll HA, Smit FJ, Gervaix A, Weerkamp

F, Vergouwe Y, et al. C-reactive protein, procalcitonin and the

lab-score for detecting serious bacterial infections in febrile children

at the emergency department: a prospective observational study. Pediatr

Infect Dis J. 2014;33:e273-9.

26. Mahajan P, Grzybowski M, Chen X, Kannikeswaran N,

Stanley R, Singal B, et al. Procalcitonin as a marker of serious

bacterial infections in febrile children younger than 3 years old. Acad

Emerg Med. 2014;21:171-9.

|

|

|

|

|