|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2015;52:

691-693 |

|

Short-term Ibuprofen Treatment and Pulmonary

Function in Children with Asthma

|

|

Yu-Mao Su, Che-Sheng Huang and Kong-Sang Wan

From Department of Pediatrics, Taipei City Hospital-Renai

Branch, Taiwan

Correspondence to: Dr Kong-Sang Wan, Department of

Pediatrics, Taipei City Hospital-Renai Branch, No.10, Sec.4, Renai Road,

Da An District, Taipei City 10629, Taiwan.

Email: gwan1998@gmail.com

Received: July 21, 2014;

Initial review: September 08, 2014;

Accepted: April 29, 2015.

|

Objectives: To investigate the

association between ibuprofen use and pulmonary function in children

with Asthma.

Methods: Ninety 9- to 10-year-old children

were classified into 3 groups: Study group, mild to moderate

stable asthmatic children with self-reported aspirin allergy and no

history of anaphylaxis; Allergy control group: atopic children

(allergic rhinitis/atopic dermatitis); Healthy control group:

non-atopic healthy children. None of the participants in the atopic and

healthy control groups had a history of aspirin allergy. All received

ibuprofen 4 times a day for 3 consecutive days. Forced expiratory volume

in the first second (FeV1) and fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO)

measurements were performed before and after ingestion of ibuprofen

daily for 3 days.

Results: In the study group, a decrease in

FeV1 and increase in FeNO levels were observed after taking ibuprofen

for 2 days. The atopic control group showed only an increase in FeNO but

not FEV1. In the healthy control group, both FeV1 and FeNO were

unchanged from baseline.

Conclusions: The results showed that

cross-reactive non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug hypersensitivity may

exist between ibuprofen and aspirin. This raises the possibility that

asthma exacerbation could be mediated by ibuprofen ingestion.

Keywords: Asthma, Exhaled nitric oxide, FeV 1,

Ibuprofen, NSAID.

|

|

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are

one of the most commonly involved groups of medicines in

hypersensitivity drug reactions. About 76% of patients who are

hypersensitive to NSAIDs have cross-intolerance, and atopy can be a

predisposing factor in patients with cross-intolerance [1,2]. Aspirin

intolerance in asthmatic patients has been reported to be underdiagnosed

[3]. In those who are allergic to NSAIDs, acetylsalicylic acid (18.2%)

and ibuprofen (18.2%) are the most frequently identified drugs [4]. In

patients with hypersensitivity reactions to NSAIDs, 76% have

cross-intolerance and 24% are selective responders. The most important

drugs involved in cross-intolerance are propionic acid derivatives, in

most cases ibuprofen, and in sustained-release pyrazolones. In

cross-intolerance, the most frequently reported clinical entities are

urticaria and angioedema; however, the airway can also be involved [1].

It has been suggested that the possibility of ibuprofen-induced

bronchospasms should be considered before administering ibuprofen to

children with asthma [5]. Moreover, this asthmatic reaction is

dose-dependent and can occur with sub-therapeutic doses [6]. We,

therefore, investigated the effect of short-term ibuprofen treatment on

pulmonary function in asthmatic children.

Methods

Ninety 9- to 10-year-old children (49 males) were

enrolled and divided into three groups of 30 children each. The Study

group comprised of children with mild to moderate asthma as classified

by the GINA guidelines and a self-reported history of aspirin-allergy.

The Allergic control group had children with allergic rhinitis or atopic

dermatitis, and the Healthy control group included healthy children

attending our hospital for vaccination. The children in the allergy and

healthy control groups had no history of aspirin-allergy. Forced

expiratory volume in the first second (FeV 1)

and Fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) measurements (NIOX MINO

system, Phadia) were performed for each participant every morning before

breakfast for 3 consecutive days. The participants took ibuprofen 2.5

mg/kg 4 times a day. We defined bronchospasm as a

³20% decrease from

baseline in FeV1, and

ibuprofen-sensitivity as bronchospasm following administration of

ibuprofen. Asthma exacerbation was defined as an increase in FeNO level

from baseline (20 ppb) with increased coughing frequency and chest

tightness clinically, increased use of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) or

short-acting beta-agonists, and a decrease in PaO2

of less than 90%. Children taking systemic steroids within one week of

the initiation of the study were excluded. This study was approved by

the Institutional Review Board of our hospital, and all of the

participants’ parents or guardians provided written informed consent.

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences software

version 12 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all

statistical analyses. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

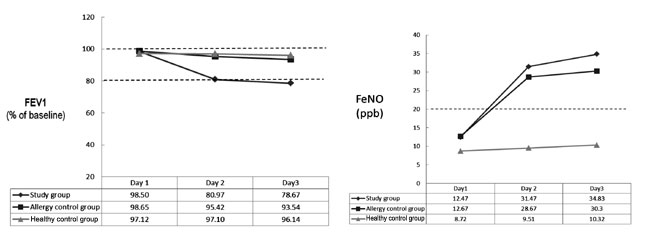

After the children had received the intervention for

two days, a worsening of pulmonary function and asthma exacerbation was

seen in a significant number of children in the study group (Table

I). The allergy control group only showed an increased FeNO level

but no change in FeV 1. In

the healthy control group, both PFT and FeNO were maintained at the

baseline level (Fig. 1).

TABLE I Clinical and Laboratory Parameters in the Study Population After Taking Ibuprofen for Two Days

|

Study group |

Allergic control group |

Healthy control group |

P value |

|

(n=30) |

(n=30) |

(n=30) |

|

|

FEV1 (% of prediction) |

80.97 ± 5.35 |

95.42 ± 4.79 |

97.10 ± 1.12 |

<0.001 |

|

FeNO (ppb) |

31.47 ± 4.78 |

28.67 ± 3.85 |

9.50 ± 1.57 |

<0.001 |

|

PaO2 (mm Hg) |

85.23 ± 2.40 |

92.60 ± 3.45 |

97.17 ± 2.09 |

<0.001 |

|

*Increased cough and/or chest tightness |

30 (100) |

6 (20.0) |

0 |

<0.001 |

|

*Increased ICS dose and/or SABA use |

30 (100) |

5 (16.7) |

0 |

<0.001 |

|

FEV1: Forced expiratory volume in the first second; FeNO:

Fractional exhaled Nitric Oxide; PaO2: Partial pressure of

Oxygen in arterial blood; ICS: Inhaled corticosteroid; SABA:

short acting beta-agonist. Values in mean ± SD or * No. (%). |

|

|

Fig. 1 (a) The FEV1 changes in the

study group after treatment of ibuprofen for 3 consecutive days;

(b) The FeNO changes in the study group after treatment with

ibuprofen for 3 consecutive days.

|

Discussion

As ibuprofen has cross-intolerance with aspirin, the

children with mild to moderate asthma in this study had an increased

frequency of coughing with or without short of breath, and required

double the dose of ICS or the use of short acting beta-agonists to ease

the exacerbation of asthma symptoms. Patients with aspirin-exacerbated

respiratory diseases typically experience severe bronchoconstriction

and/or rhinoconjunctival reactions to aspirin and other NSAIDs, even

those which they have not encountered previously [7].

Aspirin-intolerance, as determined in broncho-provocation studies, may

be apparent in 5% of asthmatic children [8]. Palmer reported that

NSAID-exacerbated asthma may occur in up to 2% of asthmatic children

[6].

Kanabar, et al. [9] reported that ibuprofen

use was associated with a low relative risk for hospitalization (0.63)

and outpatient visits (0.56) for asthma compared with acetaminophen. In

addition, Kidon, et al. [10] also reported that ibuprofen at

antipyretic doses may cause acute respiratory problems in only a very

small number of mild to moderate asthmatic children. Furthermore, a

cross-reactive hypersensitivity response to NSAIDs was reported in 45%

of young Asian atopic children through their history, and in 25% through

diagnostic challenge [11].

Of the patients with hypersensitivity reactions to NSAIDs, 76% had

cross-intolerance and 24% were selective responders. The most important

drugs involved in cross-intolerance are propionic acid derivatives, in

most cases ibuprofen, and in selective responders, pyrazolones. In

cross-intolerance, the most frequent clinical entities are urticaria and

angioedema, and to a lesser extent airway involvement [1]. Jenkins,

et al. [12] reported that cross-intolerance to doses of NSAIDs was

present in most patients with aspirin-induced asthma (ibuprofen, 98%;

naproxen, 100%; and diclofenac, 93%). On the other hand, beneficial

effects of ibuprofen have been reported in cystic fibrosis [13]. In

addition, due to the inflammatory pathogenesis of asthma, the

anti-inflammatory effect of ibuprofen may possibly reduce morbidity in

children with asthma.

There are several limitations to this study. First,

the number of enrolled subjects was limited. Second, other NSAIDs such

as diclofenac sodium and naproxen were not evaluated for

cross-intolerance comparative studies. Third, both sub-clinical and high

doses of ibuprofen were not included.

Ibuprofen is used extensively among children as an

analgesic and antipyretic agent. However, whether children with asthma

or are at risk of developing asthma should avoid the use of ibuprofen

still remains to be elucidated [15]. In Taiwan, ibuprofen is commonly

used over-the counter and in hospitals due to the advantage of a less

frequent dose and a longer duration of action. In clinical practice, the

possibility of ibuprofen-induced bronchospasm should be considered

before administering ibuprofen to children with asthma.

|

What This Study Adds?

• Exposure to ibuprofen worsens the pulmonary

functions and exacerbates asthmatic symptoms in children with

asthma having aspirin-allergy.

|

References

1. Dona I, Blanca-Lopez N, Cornejo-Garia JA, Torres

MJ, Laguna JJ, Fernández J, et al. Characteristics of subjects

experiencing hypersensitivity to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs:

patterns of response. Clin Exp Allergy. 2011;41:86-95.

2. Szczeklik A, Stevenson DD. Aspirin-induced asthma:

advances in pathogenesis and management. J Allergy Clin Immunol.

1999;104:5-13.

3. Szczeklik A, Nizankowska E. Clinical features and

diag-nosis of aspirin induced asthma. Thorax. 2000;55:S42-4.

4. Gomes E, Cardoso MF, Praca F, Gomes L, Mariño E, Demoly

P. Self-reported drug allergy in general adult Portuguese population.

Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:1597-601.

5. Debley JS, Carter ER, Gibson RL, Rosenfeld

M, Redding GJ. The prevalence of ibuprofen-sensitive asthma in children:

a randomized controlled bronchoprovocation challenge study. J Pediatr.

2005;147:233-8.

6. Palmer GM. A teenager with severe asthma

exacerbation following ibuprofen. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2005;33:261-5.

7. Stevenson DD. Aspirin sensitivity and

desensitization for asthma and sinusitis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep.

2009;9:155-63.

8. Jenkins C, Costello J, Hodge L. Systematic review

of prevalence of aspirin induced asthma and its implications for

clinical practice. BMJ. 2004;7437:434-7.

9. Kanabar D, Dale S, Rawat M. A review of ibuprofen

and acetaminophen use in febrile children and the occurrence of

asthma-related symptoms. Clin Ther. 2007;29:2716-23.

10. Kidon MI, Kang LW, Chin CW, Hoon LS, Hugo VB,

et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug hypersensitivity in

preschool children. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2007;3:114-22.

11. Kidon MI, Kang LW, Chin CW, Hoon LS, See Y, Goh

A, et al. Early presentation with angioedema and urticaria in

cross-reactive hypersensitivity to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

among young, Asian, atopic children. Pediatrics. 2005;116:e675-80.

12. Jenkins C, Costello J, Hodge L. Systematic review

of prevalence of aspirin induced asthma and its implications for clinic

practice. BMJ. 2004;328:434.

13. Lands LC, Milmer R, Cantin AM, Manson D, Corey

M. High-dose ibuprofen in cystic fibrosis: Canadian safety and

effectiveness trial. J Pediatr. 2007;151:249-54.

14. Kauffman RE, Lieh-Lai M. Ibufrofen and increased

morbidity in children with asthma: fact or fiction? Paediatr Drugs.

2004;6:267-72.

15. Risser A, Donovan D, Heintzman J, Page T. NSAID prescribing

precautions. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80:1371- 8.

|

|

|

|

|