|

D

evelopment is a continuous process that occurs

normally in childhood, wherein skills are acquired in various

inter-related developmental domains. It is intricately influenced by a

combination of genetic, biological and psycho-social factors [1].

Pediatricians frequently face parental concerns regarding development

and/or behavior [2]. Some of these issues may be transient and easily

rectifiable but a small but significant proportion may actually be

harbingers of neuro-developmental disorders.

The global prevalence of developmental delay in

children is reported as 1-3%, while World Health Organization (WHO)

estimates that 15% of the world’s population lives with some form of

disability [3,4]. There is a paucity of community-based data from lower

and middle income countries (LMIC), but a similar or higher prevalence

is expected [5]. Due to improving maternal and child health care and

better neonatal and child survival, there is now a large group of

children at high risk for developmental delay in these countries. In

addition, the proportion of children experiencing poverty, ill-health,

malnutrition and lack of early stimulation – factors that adversely

affect attaining optimum developmental potential – are much more in

comparison to high income countries [1].

One of the main reasons for lack of community-based

data from India is the absence of routine developmental screening and

surveillance. Developmental surveillance is the longitudinal process of

identification and monitoring of newborns and children at high risk [6].

This comprises of eliciting parental concerns, acquiring developmental

history, identifying risk and protective factors, evaluation, and

maintenance of records [7]. Screening is the brief cross-sectional

process of evaluating children by screening tools with good psychometric

qualities (sensitivity and specificity >70-80%), that have been

norm-referenced and standardized on populations representative of the

target population [5-7]. In developed countries, both strategies are

core components of the health, education and social care systems [8].

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends developmental

surveillance of high-risk children at each health visit from birth to 3

years, and routine screening of low-risk children at 9, 18, and 24/30

months or earlier if concerns are elicited [7]. Screening for behavioral

disorders and academic/learning disorders is also recommended [9]. Hix-Small,

et al. [10] reported an increase in screening in USA after these

guidelines were framed, though it is still far from ideal. Lack of

screening means delay in detection, initiation of intervention,

increased morbidity and parental anguish, more health service

utilization and poorer prognosis [11].

Why Developmental Screening is not Routinely Practiced in India?

In India, there are multiple challenges to practice

of universal developmental surveillance and screening. Parents are

unaware of the existence and need of these services. Health care seeking

is prioritized for acute illnesses which are not appropriate

opportunities for screening. A heterogeneous population of doctors with

variable proficiency caters to the health needs of Indian children. If

parents express concerns, they are often given false assurances without

proper appraisal. Well-child visits are primarily for immunization with

a few perfunctory questions asked about development, if at all. This was

documented in a study of perceptions and practices of 90 pediatricians

from Gujrat [12]. Most participants (97.3%) reported parents expressing

developmental concerns but only 13.6% used structured tools for

evaluation. Reasons cited by those relying on informal assessment were

time constraints (72%), non-availability of treatment or referral

options (45%), and inability to use screening tools (28%). Contrary to

this common misconception, informal evaluation has been proved

unreliable in detecting developmental delay. Recognition is difficult in

early childhood unless specifically looked for in a structured way,

since changes in development are rapid, there is intra-domain overlap,

and early indicators are often subtle.

At present, exposure and training in formal

developmental screening and assessment is lacking in the post-graduate

pediatric curriculum. Pediatricians may be cognitively aware but lack

the necessary psycho-motor and communication skills to screen

effectively. There is a scarcity of developmental pediatricians.

Available assessment tools are mostly of international origin, which are

expensive, not easily available, and require training and accreditation.

Recommendations for developmental screening by the Indian Academy of

Pediatrics (IAP) are yet to be formulated. Although the ‘Persons with

Disabilities Act, 1995’ states that ‘children should be screened

annually to detect high risk cases’, the process is not outlined [13].

In 2013, the ‘Rashtriya Bal Swasthya Karyakram (RBSK)’ was

launched by the Government of India, which aims at screening for defects

at birth, diseases, deficiencies and development delays including

disabilities (4 D’s) in children between 0 to 18 years [14]. It is

envisioned that pre-school children will be screened by Anganwadi

workers using age-appropriate developmental checklists in the periphery

and the positive cases will be re-assessed by trained personnel at the

secondary and tertiary care levels. Once this swings into action there

will naturally be an upsurge of pediatric consultations by concerned

parents, which will need to be tackled responsibly. Reviews of screening

tools that may be used in LMICs are available but are hampered by lack

of clear guidelines or practice algorithms [5,15,16].

This article aims at sensitizing pediatricians,

reviewing certain general (not domain-specific) developmental screening

and monitoring tools validated for use in Indian under-five children,

and proposes an office practice paradigm.

Developmental Screening Tools in Use in India

Screening tools currently in use in India include

those developed and validated in high-income countries, translations of

the above in Indian languages, and indigenously developed tools. Each

type has its own problems. In addition to the drawbacks outlined

earlier, internationally acclaimed tools may not be suitable for our

populations due to presence of items that are culturally alien or which

lose context after translation. They also require validation on large

reference groups comprising of healthy children of the target population

without conditions averse to development like iron deficiency anemia,

malnutrition, poverty, and decreased stimulation [17]. Translations may

be understandable but still face the aforementioned drawbacks, unless

validated. Indian tools are language and culturally suitable, have been

validated but may not have optimal psychometric properties since most

were originally developed largely for community surveys by health

workers. Taking these aspects into consideration, a list of screening

tools for developmental delay popularly in use or validated in Indian

settings was compiled and those that could be administered by

pediatricians in any office setting were reviewed. Tools screening for

behavior problems or specific domains or overt disability were not

included.

Analytically Comparing Tools for Development Screening

To be able to compare tools qualitatively, it is

essential to understand their characteristics. Table I

outlines the definitions and acceptable standards of commonly used

psychometric parameters. These are important for making educated

decisions regarding quality. If screening tools are not used for their

intended purpose (i.e. screening tools being used for diagnosis

or in children outside the intended age range), reliability gets

compromised. Choice of tools also differs according to level of risk for

developmental delay; high-risk children being those with biological

and/or environmental risk factors. Constituent items of tools may be

historically based (milestones, opportunity-based skills),

performance-based or both. In contrast to developed counties, parental

interviews are not as reliable in LMICs due to poorer literacy levels,

unawareness of milestones and possibility of socially acceptable

responses being given due to associated social stigma [5,15,16].

Interpretation of a screening result as pass or fail is done by

comparing with scores derived from standardized population

norm-references or pre-decided performance criterion.

TABLE I Definitions and Acceptable Standards of Development Tool Related Psychometric Properties

|

Term |

Description |

Acceptable standard |

|

Standardization |

The uniformity of procedure in administering and scoring the

test

|

On representative

|

|

exactly as outlined by the developer of the tool.

|

population |

|

Validity |

The ability of a tool to assess what it is intended to assess in

|

70% |

|

comparison with a gold standard diagnostic tool |

|

|

Sensitivity |

Percentage of children with delay/ problem who are correctly

|

70 80% |

|

identified by the screening test

|

|

|

Specificity

|

Percentage of children without delay/ problem who are correctly |

³80%

|

|

identified by the screening test

|

|

|

Positive Predictive Value

|

Percentage of children identified with delay/ problem by the

|

30-50% |

|

screening test who do indeed have the delay/ problem |

|

|

Negative Predictive Value

|

Percentage of children identified as normally developing by the

|

|

|

screening test who are indeed developing normally |

|

|

Reliability |

How consistently similar results are obtained repeatedly |

High/ strong-

|

|

Inter-rater |

Result variability if test given by different interviewers |

coefficients>0.60 |

|

Test-retest

|

Result variability when repeated later

|

|

Deciding the Tool Best Suited for Indian Children

Hypothetically, an ideal screening tool for Indian

children is a brief, inexpensive tool with good psychometric properties,

available in Indian languages, comprising of purely

developmental/culturally-adapted items, that has been validated on

representative healthy Indian children and requiring minimal training

[17]. Such a designer tool does not exist in reality; so each

pediatrician has to make an educated choice best suited for individual

practice. Developmental tools of international origin are compared in

Table II. Only two of these have been validated in Indian

children.

TABLE II Comparison of Developmental Screening Tools of International Origin

|

Factors |

Denver DevelopmentalScreening Test II |

Bayley Infant Neuro-developmental Screen (BINS) |

Parents Evaluationof Developmental Status (PEDS)

|

Ages and stages questionnaire (ASQ)

|

Developmental* Profile II/ III

|

|

Age Format |

0-6 yearsDirectly administered |

3-24 monthDirectly administered

|

0-8 yearsParent-report |

1 -66 /3- 66 mParent report |

0-9 y/ 12 y11m Parent report

|

|

Screens/Domains |

Expressive & receptivelanguage, gross motor, fine motor,

personalsocial

|

Neurological processes, expressive and receptive functions&

cognitive |

Cognitive, expressive& receptive language fine &

gross motor, social-emotional, behavior, self-help& school |

Communication, gross motor, fine motor,problem-solving,

andpersonal adaptive skills |

Physical, Self-help/ Adaptive, Social/Social-emotional,Academic/

cognitiveand Communication

|

|

Itemsont> |

125 |

11-13 |

10

|

22-36 |

186/ 180 |

|

Scoring/ Result |

Risk category: normal/abnormal/ questionable |

Risk category: high/ low moderate |

Risk category: low/ medium/ high |

Pass/fail scores |

Total score gives domain wise age equivalents |

|

Time

|

10-20 min

|

10 min |

2-10 min |

10-15 min |

10 /20-40 min |

|

Language |

English, Spanish |

English |

English |

English, Hindi |

English |

|

Psychometric

|

Sensitivity 0.56-0.83 |

Sensitivity 0.75-0.86 |

Sensitivity 0.74-0.79 |

Sensitivity 0.70-0.90 |

Validity Coefficients*

|

|

properties |

Specificity 0.43-0.80

|

Specificity 0.75-0.86 |

Specificity 0.70-0.80 |

Specificity 0.76-0.91

|

0.52-0.72

|

|

Validated in India |

Not validated |

Not validated |

Sensitivity 62% Specificity 65% |

Sensitivity 83.3% Specificity 75.4% |

Not validated but used extensively |

|

Cost

|

$111

|

$325

|

$30

|

$249 |

$240

|

|

Access site |

http://www.denverii.com/ |

www.pearsonassessments.com

|

www.pedstest.com

|

www.brookespub lishing.com/asq |

www.wpspublish.com

|

|

*Internal consistency: 0.89-0.97 and Test-retest reliability:

0.81-0.92

|

The Denver Developmental Screening Test (DDST) is a

very popular and frequently used international screening test [18-20].

However, its low specificity (43%) leads to over identification of false

positives, parental apprehension, and burden on the system for diagnosis

and intervention. Hence it is no longer considered appropriate for the

purpose of screening. The Bayley Infant Neuro-developmental Screen

(BINS) has been used for monitoring children at moderate to severe high

risk [21,22]. Though psychometric properties are acceptable, its

drawbacks are lack of validation in Indian children and inability to

screen children beyond 2 years of age. The Ages and Stages Questionnaire

(ASQ) is a parent- completed questionnaire with acceptable properties

[23]. In a study by Juneja, et al. [24], ASQ was validated

against the Developmental Scale for Assessment of Indian Infants. After

being translated into Hindi and substitution of a few culturally

inappropriate items, this version of ASQ was administered to parents by

an interviewer to screen children aged 4,10,18 and 24 months with both

high and low risk. The overall sensitivity in detecting developmental

delay was 83.3% (higher for the high-risk children), specificity 75.4%

and negative predictive value 84.6%. ASQ has the potential to be used in

India after being translated into local languages if interviewer-

administration replaces parent-completion when required.

Studies in the West have shown that asking parents

about development concerns is reliable for assessment [25]. Parent

Evaluation of Developmental Status (PEDS) considers concerns as either

‘not predictive’ or ‘predictive’ of developmental disabilities. The

latter categorizes children as having High, Moderate or Low risk of

developmental disabilities. Each is linked with related management

protocols: referral, more screening or continued surveillance,

respectively. PEDS has been found reliable in other developing

countries; however, there is limited literature from India [19,26,27].

The only available study from India was by Malhi, et al. [28] in

which it was compared with Developmental Profile II (DP II) and Vineland

Social Maturity Scale. Psychometric properties were found to be

sub-optimal. The authors suggested that PEDS could be used to identify

children requiring in-depth screening in situations involving time

constraints. The limitations of this study were use of another screening

tool as gold standard and a small sample size. Further research is

warranted before its value in the Indian context is clarified [5,15].

Developmental Profile III is an updated version of DP II that screens

for developmental delay in five key areas [29,30]. Its norms are based

on a large representative sample of typically developing American

children. Although used in India frequently in numerous research

studies, it is yet to be validated in Indian children.

Indian screening tools, that were designed for

community surveys but can be used for office practice, are compared in

Table III. These are easy to perform and interpret,

inexpensive, and have been norm-referenced and standardized in

representative populations. The main drawback is less than acceptable

psychometric properties. Normative data of both Baroda Developmental

Screening Test (BDST) and Trivandrum Developmental Screening Chart

(TDSC) are derived from the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID)

which has not been re-validated since its inception more than 20 years

ago [31]. The same drawback lies in the Indian Council Medical Research

Psychosocial Developmental Screening Test (ICMR-PDST) [32,33]. In the

TDSC validation study, the gold standard that was used was not a

diagnostic tool but DDST (no longer considered suitable): so the results

may be considered questionable until re-validated against a more robust

gold standard [34].

TABLE III Comparison of Indian Developmental Screening Tools

|

Factors |

Baroda Developmental

|

Trivandrum Developmental

|

ICMR Psychosocial developmental

|

|

screening Test (BDST) |

Screening Chart (TDSC) [25] |

screening Test [27, 28] |

|

[24] |

|

|

|

Developed from |

Bayley Scales of Infant

|

Bayley Scales of Infant

|

Programme for Estimating Age-related

|

|

Development, Normative data |

Development (Baroda Norms)

|

Centiles Using Piece-wise Polynomials*

|

|

from Indian children |

|

Normative data from Indian children |

|

Age |

0 - 30 mo |

0 - 24 mo |

0-6 y

|

|

Format |

Directly administered |

Directly administered

|

Parent interview 66 items

|

|

54 items

|

17 items |

|

|

Domains |

Motor and Cognitive

|

Mental and Motor

|

Gross Motor, Vision & Fine motor,

|

|

|

|

Hearing, language & concept development,

|

|

|

|

Self Help & Social skills |

|

Scoring/ Result

|

Age equivalent and |

Within age range |

3rd, 5th, 25th, 50th, 75th, 95th & 97th

|

|

developmental

|

|

centiles given Significant delay < 3rd centile

|

|

quotient calculated |

|

(2 S.D) |

|

Training |

Minimal training

|

Minimal training |

None |

|

Setting

|

Community/ office

|

Community/ office

|

Community/ office

|

|

Time taken |

10 min

|

5 min |

Minimal

|

|

Psychometric

|

Sensitivity: 65-93%,

|

Sensitivity: 66.8%,

|

Not given |

|

properties

|

Specificity: 77.4-94.4% |

Specificity: 78.8% |

|

|

PPV: 6.67-34.37% |

|

|

|

Access site &

|

Promila Phatak,

|

MKC Nair, Child |

ICMR, Free

|

|

Cost

|

Department of Child

|

Developmental Centre

|

|

|

Development, University

|

Trivandrum, Kerala, India. |

|

|

of Baroda, India.

|

Inexpensive |

|

|

Inexpensive |

|

|

|

ICMR: Indian Council of Medical Research, PPV: Positive

Predictive value; * Child Health and Development, Maternal

and Child Health and Family Planning, Geneva, 1992. |

Development Screening Tools of the Future

Two promising screening tools may become available

for use in the near future. The first – Guide for Monitoring Child

Development (GMCD) – is a parental report-based development monitoring

tool for children between 0 to 3.5 years originally developed in Turkey

[8]. It comprises of 7 items pertaining to developmental concerns, and

takes 5-10 minutes to administer. The sensitivity and specificity are

86% and 93%, respectively. It also has an intervention package that

helps in supporting normal development and managing developmental

difficulties. A five-year project ‘Development of International guide

for monitoring child development’ is currently underway in India,

Turkey, Argentina and South Africa since 2010 [5]. The aim of this

project is to standardize GMCD for universal use in children

irrespective of demographic, cultural or linguistic considerations. The

project also aims at examining an approach in which monitoring is done

at community health clinics by trained personnel.

The second new kid-on-the-block is the INCLEN

Neurodevelopmental Screening Test (NDST) that was developed by the

composite efforts of a team of neuro-developmental experts from India

and abroad. It screens for 10 neurodevelopmental disorders (NDD): Autism

Spectrum Disorders, Learning Disorder, Attention Deficit and

Hyperactivity Disorder, Vision Impairment, Hearing Impairment,

Intellectual Disability, Speech and Language Disorders, Epilepsy,

Cerebral Palsy and other Neuro-Muscular Disorders. Diagnostic criteria

(Consensus Clinical Criteria) have been developed for establishing each

diagnosis which are sequentially applied according to an algorithm when

the screening test is positive [35]. Application of the NDST in a

recently concluded multi-centric validation study in rural, urban, hilly

and tribal areas revealed that the prevalence of ≥1 NDD in children

aged 2-9 years ranged between 7.5-18.5% [36].

Developmental Screening in Office Practice

Setting up routine screening practice involves

creating parental awareness and demand, finding the right opportunity,

tool selection, acquisition and training in administration, scoring,

interpreting results and counselling. This entails planning when, where,

and how screenings will be accomplished, devising a method for

documenting observations and maintaining records, communicating results

to parents, referring to experts for further evaluation when required

and scheduling future screenings. Parents can be sensitized by

information pamphlets and office displays. Since visits for acute

illnesses are not appropriate opportunities; a practical option would be

to club screening with pre-existing scheduled visits like immunization

and vitamin A prophylaxis. A system needs to be devised to document

results, maintain and update records at subsequent visits. Comparison

with previous records helps to recognize potential developmental

problems or regression, deviancy or dissociation. Experience from other

countries has shown that time actually gets saved since it takes the

same time that would otherwise have been spent in unstructured

questioning and answering other parental queries. Ultimately evaluation

time becomes predictable, detection rate increases, parent and provider

satisfaction level increases and office attendance increases as parents

start appreciating the monitoring process.

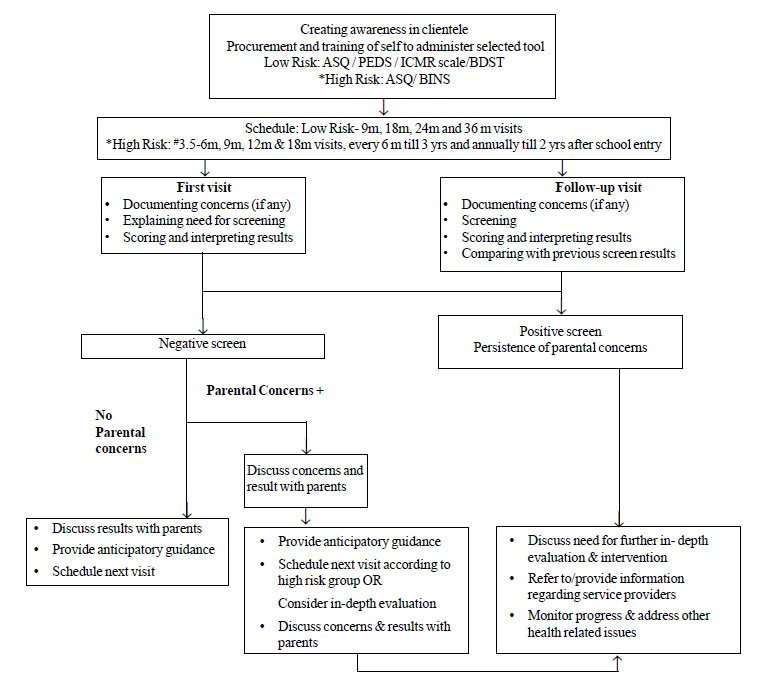

An Algorithmic Approach to Developmental Screening

Based on the advantages and drawbacks of the

tabulated tools and until consensus statements are formulated by expert

groups, the authors suggest a potential practice paradigm for

pediatricians based on degree of risk of developmental delay (Fig.

1).. Pr. Preliminary steps involve creating awareness, procuring tools

according to the type of patients encountered (low-risk, high-risk or

both), and achieving competency in administration, scoring and

interpretation. The schedule of screening and follow up monitoring will

differ according to level of risk.

|

|

*Neonates, Infants or children with

≥1 High risk

factors viz., Genetic: positive family history of illness

associated with neurodevelopmental morbidity; Biological: acute

& chronic illnesses, nutritional (macro & micro) deprivation;

Environmental: exposure to poverty, violence, neglect,

teratogens, arsenic, lead, drugs, etc.; Psycho-social:

illiteracy, lack of stimulation, learning opportunities, poor

parenting skills, parental illness or substance abuse, maternal

depression, etc.; Presence of any parental concerns regarding

development. #Abnormality present at 3.5 months: refer to text

(discussing parental concerns & test outcomes).

Fig.1 Proposed schema of office based

developmental screening and surveillance.

|

Discussing Parental Concerns and Test Outcomes

Parental concerns should always be asked. In the

initial visit, if the parent of a low risk child expresses developmental

concerns, the pediatrician is expected to discuss these with the parents

and offer options of more frequent and earlier monitoring (as in the

high risk group) or referral for an in-depth evaluation even if the

screen is negative. If the parents opt for the former and the concerns

persist at the next visit, immediate referral is warranted. If not,

monitoring should continue as for the high-risk group, In this group,

the first visit recommended by AAP is 4-6 months (coinciding with the

2nd or 3rd immunization visit). The corresponding immunization visit in

India would be at 3.5 months. At this age, a small proportion of infants

display transient benign tone abnormalities that may be mistaken as

pathological. In these instances, the pediatrician should make a note in

the child’s records and schedule a repeat visit after a month, without

unduly alarming the parents. If it persists, in-depth evaluation would

be required.

Once screening is complete, it is important to

properly convey the significance of the results. If negative, parents

should be reassured that development is currently appropriate,

anticipatory guidance should be given about expected milestones and the

necessity of returning for the next screening visit should be explained

and scheduled. If positive, the implications need to be discussed in

depth with the parents, and they should be counseled about the need of

diagnostic evaluation and start of stimulation or intervention as

indicated post evaluation. Since parents have intrinsic faith in us as

health care providers of their children, it is our moral responsibility

to be instrumental in arranging referrals (by providing contact details

or direct communication) as well as providing continual medical help and

moral support. It is good practice to develop a two-way communication

system with service providers to instill confidence in parents regarding

management issues.

Screening should be considered the initial step of

intervention services [37]. Unfortunately, it is common practice to

falsely reassure or delay referral to alleviate parental anxiety. Actual

practice should be ‘Refer not defer.’ Failing to refer for diagnosis and

intervention after detection on screening is considered unethical [38].

In developed countries, a referral rate of 1/6 children screened is

considered optimal [39]. It is important to understand that starting

multi-disciplinary intervention (speech and language therapy,

occupational therapy, physical therapy, special educational services,

etc) should proceed in parallel to diagnosis-establishment and not

afterwards. In addition to formal intervention, pediatricians must

become familiar with home-based intervention strategies that should be

shared with the parents. Development oriented packages have been

combined with tools like ‘Integrated Management of Child Illnesses –

Care for Development’ (WHO/UNICEF), GMCD, TDSC and Developmental

Assessment Tool for Anganwadis (DATA) or are already in practice at the

community level via National Rural Health Mission, RBSK, Integrated

Child Development Schemes, and other agencies, the details of which are

available, can be practiced by parents at home, and have been proven to

be beneficial [8,14,34,40-45].

Conclusions

Many parents and children struggle in their daily

lives due to problems arising from undetected development delay.

Considering the widespread prevalence of developmental problems, the

pediatrician must remain vigilant. By adopting developmental screening

and surveillance, one can ensure a systematic approach to children with

developmental concerns and help improve their future. Both strategies

are integral parts of child healthcare, benefit the individual child and

society, and also protect the doctor from possible future litigation. In

this review, an attempt has been made to sensitize colleagues to the

importance of screening and surveillance, compare existing screening

tools and propose those suitable for Indian children along with

strategies for incorporation into office practice. There is a strongly

felt need to develop more culturally appropriate, norm-based, valid and

reliable Indian developmental screening instruments. We strongly urge

that a consensus be formulated at the National level by experts on

appropriate developmental surveillance and screening recommendations.

Ultimately, earlier recognition of developmental delay results in better

inclusion of affected individuals in society, establishment of

prevalence data, educated health policy decisions, and resource

allocation at the Government level.

Contributors: SBM: devised the review paper

concept and will stand as guarantor. All authors helped in the

literature search and selection of articles appropriate for the purpose

of the review; SBM: drafted the manuscript with critical inputs from SA,

VK and RS. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding : None; Competing interests: None

stated.

References

1. Grantham-Mc Gregor S, Cheung YB, Cueto S, Glewwe

P, Richter L, Strupp B, et alelopment in developing

countries: Developmental potential in the first 5 years for children in

developing countries. Lancet. 2007;369:60-70.

2. Lynch TR, W2. Lynch TR, Wildman BG, Smucker WD. Parental

disclosure of child psychosocial concerns: relationship to physician

identification and management. J Fam Pract. 1997;44:273-80.

3. Bellman M, Byrne O, Sege R. Developmental

assessment of children. BMJ: 2013: 346;e8687.

4. World Health Organization, World Bank. World

report on disability. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2011. Available

from: URL:http://www.who.int/disabilities/world_report/2011.

Accessed January 15, 2014.

5. Krishnamurthy V, Srinivasan R. In: Childhood

Disability Screening Tools: The South East Asian Perspective. A Review

for the WHO Office of the South East Asian Region. Mumbai. WHO, 2011.

6. Dworkin PH. British and American recommendations

for developmental monitoring: the role of surveillance. Pediatrics.

1989;84:1000-10.

7. Council on Children with Disabilities, Section on

Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics, Bright Futures Steering Committee,

Medical Home Initiatives for Children with Special Needs Project

Advisory Committee. Identifying infants and young children with

developmental disorders in the medical home: an algorithm for

developmental surveillance and screening. Pediatrics. 2006;118:405-20.GN="JUSTIFY">8. Ertem IO, Dogan DG, Gok CG, Kizilates SU, Caliskan

C, Atay G, et al. A guide for monitoring child development in

low- and middle-income countries. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e581-89.

9. Macias MM, Lipkin PH. Developmental surveillance

and screening: refining principles, refining practice. How you can

implement the AAP’s new policy statement. Contemp Pediatr. 2009;26:72-76.

10. Hix-Small H, Marks K, Squires J, Nickel R. Impact

of implementing developmental screening at 12 and 24 months in a

pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2007;120:381-9.

11. Radecki L, Sand-Loud N, O’Connor KG, Sharp S,

Olson LM. Trends in the use of standardized tools for developmental

screening in early childhood: 2002-2009. Pediatrics. 2011;128:214-19.

12. Desai PP, Mohite P. An exploratory study of early

intervention in Gujrat State, India: Pediatricians’ perspectives. J Dev

Behav Pediatr. 2011;32:69-74.

13. Persons with Disabilities (equal opportunities,

protection of rights and full participation) Act, 1995. Part II, section

1 of the Extraordinary Gazette of India, Ministry of Law, Justice and

Company affairs (legislative department). Available from: URL:

http://socialjustice.nic.in. Accessed December 27, 2013.

14. National Rural health mission, Ministry of Health

and Family Welfare, Government of India. Rashtriya Bal Swasthya

Karyakram (RBSK) Child Health Screening and Early Intervention Services

Under NRHM: Operational Guidelines. Nirman Bhavan, New Delhi. 2013.

15. Robertson J, Hatton C, Emerson E. The

identification of children with or at significant risk of intellectual

disabilities in low and middle income countries: a review. CeDR Research

Report. 2009:3

16. Fernald LCH, Kariger P, Engle P, Raikes A.

Examining Early Child Development in Low Income countries: A Toolkit for

the Assessment of Children in the First Five Years of Life. World Bank

Human Development Group. 2009

17. Lansdown RG. Culturally appropriate measures for

monitoring child development at family and community level: A WHO

collaborative study. Bull World Health Organ. 1996;74:283 90.

18. Glascoe FP, Byrne KE, Ashford LG, Johnson KL,

Chang B, Strickland B. Accuracy of Denver II in development screening.

Pediatrics. 1992;89:1221-5.

19. Glascoe FP, Byrne KE. The accuracy of three

developmental screening tests. JEI 1993; 17:268-379.

20. Frankenburg WK, Dodds J, Archer P, Shapiro H,

Bresnick PB. Denver II: A major revision of re-standardization of Denver

Developmental Screening Tool. Pediatrics 1992; 89:91-7.

21. Aylward GP. The Bayley Infant Neuro-developmental

Screener. San Antonia, Tex: Psychological Corporation 1995.

22. Macias MM, Saylor CF, Greer MK, Charles Jm, Bell

N, Katikaneni LD. Infant screening: the usefulness of the Bayley Infant

Neurodevelopmental Screener and the Clinical Adaptive Test/Clinical

Linguistic Auditory Milestone Scale. J Dev Behav Pediatr.

1998;19:155-61.

23. Bricker D, Squires J, Potter L. Revision of a

parent completed screening tool: Ages and Stages Questionnaires. J

Pediatr Psychol. 1997;32:313-28.

24. Juneja M, Mohanty M, Jain R, Ramji S. Ages and

Stages Questionnaire as a screening tool for developmental delay in

Indian children. Indian Pediatr. 2012;49:457-61.

25. Majnemer A, Rosenblatt B. Reliability of parental

recall of developmental milestones. Pediatr Neurol. 1994;10:304-8.

26. Glascoe FP. Parents concerns about children’s

development: pre-screening technique or screening test. Pediatrics.

1997;99:522-8.

27. Pritchard MA, Colditz PB, Beller EM. Parents

evaluation of developmental status in children with a birthweight of

1250 gm or less. J Paediatr Child Health. 2005;41:191-6.

28. Malhi P, Singhi P. Role of Parents Evaluation of

Developmental Status in detecting developmental delay in young children.

Indian Pediatr. 2002;39:271-5.

29. Alpern G, Boll T, Shearer M. Developmental

Profile II (DP II). Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services;1986.

30. Developmental Profile 3rd Ed. Revised and

updated. An Accurate and an Efficient Means to Screen for Development

delays. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services;2004.

31. Phatak AT, Khurana B. Barado Developmental

Screening Test for infants. Indian Pediatr. 1991;28:31-7.

32. Vazir S, Naidu AN, Vidyasagar P, Landsdown RG,

Reddy V. Screening Test for Psychosocial development. Indian Pediatr.

1994;31:1465-75.

33. Malik M, Pradhan SK, Prasuna JG. Screening for

psychosocial development among infants in an urban slum of Delhi. Indian

J Pediatr. 2007;74:841-5.

34. Nair MK, George B, Lakshmi S, Haran J, Sathy N.

Trivandrum developmental screening Chart. Indian Pediatr.

1991;28:869-72.

35. Gulati S, Aneja S, Juneja M, Mukherjee S,

Deshmukh V, Silberberg D, et al. INCLEN diagnostic tool for neuro-motor

impairments (INDT-NMI) for primary care physicians: Development and

validation. Indian Pediatr. 2014;51:613-9.

36. Silberberg D, Arora N, Bhutani V, Durkin M,

Gulati S. Neuro-developmental disorders in India – An INCLEN study.

Neurology. 2013;80:IN6-2.001.

37. Early Headstart National resource Centre.

Developmental Screening, Assessment and Evaluation: Key Elements for

Individualizing Curricula in Early Headstart Programs. Available from

http://www.zerotothree.org. Accessed December 27, 2013.

38. Perrin E. Ethical questions about screening. J

Dev Behav Pediatr. 1998;19:350-2.

39. Glascoe FP. Screening for developmental and

behavioral problems. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2005;11:173-9.

40. Department of Child and Adolescent Health

Department, WHO. IMCI Care for Development. Available from:

http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent health. Accessed

November 19, 2013.

41. Nair MKC, Russell PS, Rekha RS, Lakshmi MA, Latha

S, Rajee K, et al. Validation of Developmental assessment Tool

for Anganwadis (DATA). Indian Pediatr. 2009;46:S27-35.

42. D. Landis, J.M. Bennett, M.J. Bennett, editors. Handbook

of Intercultural Training. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Publications; 2004.

43. Nair MKC. Early stimulation CDC Trivandrum Model.

Indian J Pediatr. 1992;59:662-7.

44. Nair MKC. Early Child Development - Kerala Model.

Global Forum for Health research, Forum 3 Geneva: WHO 1999.

45. World Health Organization, UNICEF. Counsel the

Family on Child Development-Counseling Cards. Available from:

http://www.unicef.org/earlychildhood. Accessed December 27, 2013.

|