|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2011;48: 633-636 |

|

An Observational, Health Service Based Survey

for Missed Opportunities for Immunization |

|

Mamta Muranjan, Chhaya Mehta and *Abhijit Pakhare

From the Departments of Pediatrics and *Preventive and

Social Medicine, Seth GS Medical College and KEM Hospital, Parel, Mumbai,

India.

Correspondence to: Dr Mamta Muranjan, 3rd floor, Suman

Apartments, 16 B, Naushir Bharucha Road,

Tardeo, Mumbai 400 007, India.

Email: [email protected]

Received: September 22, 2010;

Initial review: September 24, 2010;

Accepted: December 03, 2010.

Published online: 2011 May 30.

PII: S09747559INPE000272-2

|

|

Abstract

Studies cite missed opportunities for immunization (MOI)

as a contributor to under-vaccination. The present prospective survey

aimed at determining the magnitude of MOI, its contribution to

under-vaccination, and identifying risk factors for MOI. Mothers of 1384

indoor patients £6 years were

interviewed. There were 266 (19.2%) children with MOI, accounting for

79.6% of under-vaccination and 93% of under-vaccination time. MOI

occurred significantly more often with home delivery (P <0.001,

Odds ratio 5.1), incomplete or incorrect maternal knowledge of

immunization (P=0.001, Odds ratio 4.8) and, general practice and

non-Pediatric/ non-Medical college based practice (P=0.001, Odds

ratio 4.0). The impact of sociodemographic factors on likelihood of MOI

was not significant.

Key words: Causes, India, Missed, Under-vaccination,

Opportunities.

|

|

M

issed opportunities for immunization (MOI) is defined as missing

the benefit of getting immunized by the partially or unimmunized child,

during a visit to the health facility for check up or illness, when there

is no particular contraindication for that particular immunization as per

the National Policy [1]. The global magnitude of MOI is 0 to 99% [2] and

9-81% in India [1,3-5]. Reducing MOI is the easiest and immediate remedy

to improve vaccine coverage at no extra cost, by exploiting existing

resources [2]. There is, therefore, an urgent need to examine the

magnitude and factors responsible for MOI, to rapidly achieve the National

immunization targets. We conducted this study to determine the magnitude

and risk factors at a tertiary care institution.

Methods

Over a period of one year, consecutive indoor patients

who fulfilled the inclusion criteria (age

£6 years, availability

of the mother and road to health card, Government of India card or private

physician’s card or verbal recall of the mother as proof of immunization,

and proof of a previous visit to a health care facility) were recruited

after approval by the Institutional Ethics Committee and obtaining

informed consent. Patients dying during admission and under-vaccinated

children without a prior health care visit were excluded. The mother was

interviewed within 24 hours of admission to avoid bias caused by

immunization related intervention. Demographic data and information about

the health care facility visit (type of service and qualifications of the

attending physician, reason for the visit, previous visits with dates if

available for present or prior complaints and diagnosis at those visits)

were recorded. The interview also assessed whether the immunization card

had been reviewed or immunization history elicited at a prior visit,

whether any contraindication to vaccination was present then and in

absence of a contraindication, whether the child had been vaccinated or

immunization related information given to the parent. Data recorded for

Universal Immunization Program (UIP) vaccines was dates of immunization

and age at administration of the vaccine. Difference between the recommended

age and the actual age of immunization and the number of weeks past due

was determined for each under-vaccinated child for every vaccination. For

under-vaccinated children with MOI, the number of weeks accounting for MOI

was calculated by the total time overdue for each child with MOI. An

estimate of the number of weeks of under-vaccination accounted by MOI and

the proportion of under-vaccination attributable to MOI was calculated.

Children detected to have MOI were referred to the immunization clinic for

the due vaccination. The data was analyzed using the Chi square test for

univariate analysis and logistic regression for multivariate analysis (SPSS

software version 15). All analysis was carried out at 5% significance (P<0.05).

Results

Inclusion criteria were fulfilled by 1401 amongst 4196

indoor admissions. Seventeen children less than 8 weeks of age were

excluded (not yet beyond time when eligible). Thus, 1384 children were

analyzed (60.5% males). The mean age was 100.7 ±88 weeks (range 3.7-312.9

weeks). At least one vaccine was received by 1296 (93.6%), 88 (6.4%) were

unimmunized and 1050 (76%) children were fully immunized (UIP schedule)

[877 (63.5%) age appropriate immunization, 173 (12.5%) up to date but not

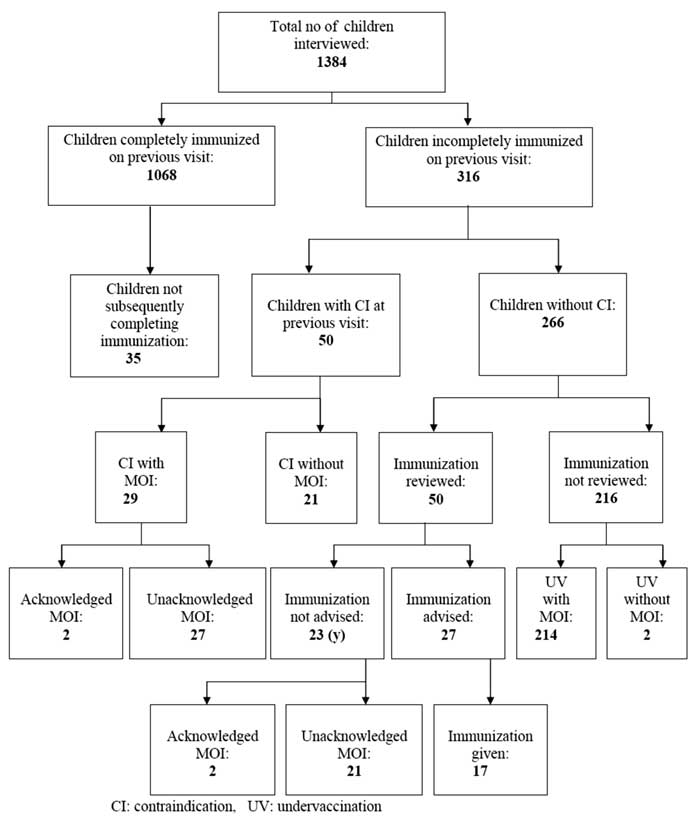

age appropriately immunized]. The immunization status is presented in

Fig.1.

|

|

Fig. 1 Immunization status of the study population.

|

Under-vaccination was observed in 24% of children

(334). MOI accounting for 79.6% of under-vaccination was present in 266

(19.2%). Almost all MOI (98.5%) were unacknowledged. Sixty-eight cases

(4.9%) were under-vaccinated but without a MOI. For a child with MOI, if

each vaccine missed was considered as a missed opportunity, then 1243

vaccinations were missed (4.67 missed vaccinations child). If each visit

when vaccination was missed was considered a missed opportunity, 702

visits were associated with MOI (2.64 missed opportunities child).

Median age at vaccination and the difference between

recommended and actual age of vaccination could be determined in 96

children with MOI having records with date of vaccination (Table

I). Of 2473.1 weeks of under-vaccination, MOI accounted for 2299

weeks. The proportion of under-vaccination weeks attributable to MOI was

92.9%.

Table I

Median Age and Difference Between Recommended and Actual Age of Vaccination in

Children with MOI (n=96)

|

Vaccine |

Median age (weeks) |

Difference (weeks) |

|

BCG |

1.7 |

5.5 |

|

OPV/DPT1 |

8 |

0.8 |

|

OPV/DPT2 |

13.7 |

2.2 |

|

OPV/DPT3 |

18.4 |

2.5 |

|

Measles |

42.7 |

1.1 |

|

MOI: Missed opportunities for immunization |

The demographic parameters of children with MOI (n=266)

were comparable to those who were under-vaccinated (n=68) in terms

of gender, religion, birth order, residence, maternal age, and

socio-economic status. MOI occurred during a visit for an acute illness in

80.5% of cases, for a chronic disease in 18.8% and a well child visit in

0.7%. The type of health facility visited was general practice (45.5%),

medical college (23%), practicing pediatrician (15.4%), public health

facility (6%), private institution (8.6%) and an alternative medical

practice (1.5%). The qualification of the health care provider was MBBS

(50.4%), post-graduate degree in Pediatrics (43.6%), degree in alternative

medicine (3.4%) and super-specialty or non-Pediatric degree (2.6%). The

reasons for MOI were immunization history not reviewed (94%), false

contraindication (2.2%), wrong immunization history (1.5%), physician not

advising immunization (1.1%), unavailability of immunization card (0.7%),

and visit not on ‘immunization day’ (0.5%).

MOI occurred significantly more often with home

delivery, incomplete or incorrect maternal knowledge of immunization, and

general practice and non-Pediatric/ non-Medical college based practice

[odds ratios: 5.1 (95% CI 2.3, 11.0), 4.8 (95% CI 1.2, 18.5) and 4.0 (95%

CI 1.9, 8.3), respectively]. Testing with Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness of

fit test indicated fitness of data in the model.

Discussion

The present study documents that 80% of

under-vaccination and 93% of under-vaccination time was due to MOI,

occurring during acute illness visits. Almost all MOI were unacknowledged,

attributable to oversight on the part of the health care provider in

obtaining history of immunization in 94% of cases. This underscores the

necessity of implementing interventions in office practice to reduce MOI

including screening a child for eligibility at every preventive or

curative visit, a tracking system to alert the physician when immunization

is due, recording dates of immunization, and ensuring caregivers carry the

immunization card at every visit [2]. Similarly, every hospital admission

must be exploited as an opportunity to immunize the eligible or advise the

due vaccine at discharge.

Previous studies have implicated provider

misconceptions like avoiding immunization during minor illness as a

significant predictor for MOI [6]. Though illness characteristic was not

significantly predictive of MOI in this study, the likelihood of MOI was

higher with visits to non-Pediatric/non-Medical college based practice

including General Practitioners. This is relevant as a large proportion of

health care delivery in India is by General Practitioner, who often are

the first and only contact for patients [7, 8]. Their correct compliance

with the National vaccination policy is critical for its success. Our

study draws attention to the urgency of corrective measures to encourage

desirable immunization practices such as simultaneous vaccination, safety

of vaccination during mild acute illness and knowledge of true

contraindications amongst other practitioners [2].

Earlier studies have documented that maternal knowledge

about vaccines and contraindications for immunization was sub-optimal

[9-11]. Many harbored erroneous beliefs and misconceptions, especially

about vaccinating during acute illness [6, 9-14]. However, maternal

acceptability of immunization was documented to be high in those with MOI

[3]. Therefore education about the diseases being targeted, nature and

timing of vaccines, their benefits and adverse effects, and acceptance of

immunization during minor febrile illnesses will be critical to empower

mothers to demand vaccination and reduce drop-out [6,11-13,15].

In conclusion, MOI can be tackled by accomplishing the

National population policy target of 80% institutional deliveries [16],

empowering mothers to demand immunization [6,9,17] and ensuring optimum

immunization delivery by general practitioners. Periodic surveys for MOI

should be a performance indicator for delivery and utilization of

immunization services in the country [2,19].

Acknowledgment: The authors thank Dr Sanjay Oak,

Director (Medical Educations and Major Hospitals, Municipal Corporation of

Greater Mumbai) and Dean of Seth GS Medical College and KEM Hospital for

granting permission to publish the paper.

Contributors: MNM designed the study, supervised

the data collection and analysis, and wrote the manuscript. MNM will act

as guarantor of the paper. CM collected and analyzed the data and prepared

the draft. AP performed the statistical analysis and helped in drafting

the manuscript.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None stated.

|

What This Study Adds?

• Missed opportunities for immunization with a

magnitude of 19.2% was responsible for 80% of under-vaccination and

93% of under-vaccination time.

• Home delivery, incomplete or incorrect maternal

knowledge of immunization and general practice and non-Pediatric/

non-Medical college based practice were highly predictive of missed

opportunities of immunization.

|

References

1. Deivanayagam N, Nedunchelian F, Mala N, Ashok TP,

Rathnam SR, Ahmed SS. Missed opportunities for immunization in children

under 2 years attending an urban teaching hospital. Indian Pediatr.

1995;32:51-7.

2. Hutchins SS, Jansen HAFM, Robertson SE, Evans P,

Kim-Farley RJ. Studies of missed opportunities for immunization in

developing and industrialized countries. WHO Bullet OMS. 1993;71:549-60.

3. Nirupama S, Chandra R, Srivastava VM. A survey of

missed opportunities for immunization in Lucknow. Indian Pediatr.

1992;29:29-32.

4. Mitra J, Manna A. An assessment of missed

opportunities for immunization in children and pregnant women attending

different health facilities of a state hospital. Indian J Public Health.

1997;41:312.

5. Grant JP. The State of the World’s Children 1990.

UNICEF. Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press; 1990.

6. Wood D, Schuster M, Donald-Sherbourne C, Duan N,

Mazel R, Halfen N. Reducing missed opportunities to vaccinate during child

health visits. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998:152:238-43.

7. Goyal RC, Sachdeva NL, Role of general practioners

in primary health care. J Indian Med Assoc.1996;94:60-1.

8. Chansoria M, Taluja RK, Mukerjee B, Kaul KK. A study

of immunization status of children in a defined urban population. Indian

Pediatr. 1975;12: 879-88.

9. Kekre MM, Mohammad AS, Pruthvish S, Misquith D.

Speeding up universal immunization programme. Indian Pediatr.

1988;25:636-41.

10. Manjunath U, Pareek RP. Maternal knowledge and

perceptions about the routine immunization programme – a study in a

semi-urban area in Rajasthan. Indian J Med Sci. 2003;57:158-63.

11. Murthy GVS, Kumar S. Knowledge of mothers regarding

immunization in a high coverage area-need for strengthening health

education. Indian Pediatr. 1989;26: 1219-22.

12. Smith PJ, Chu SY, Barker LE. Children who have

received no vaccines: Who are they and where do they live? Pediatrics.

2004;114:187-95.

13. Bhandari B, Mandowara SL, Gupta GK. Evaluation of

vaccination coverage. Indian J Pediatr. 1990;57:197-202.

14. Bates AN, Wolinsky FD. Personal, financial, and

structural barriers to immunization in socioeconomically disadvantaged

urban children. Pediatrics. 1998;101:591-6.

15. Agarwal S, Bhanot A, Goindi G. Understanding and

addressing childhood immunization coverage in urban slums. Indian Pediatr.

2005;42:653-63.

16. National Population Policy 2000. New Delhi.

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. 2000.

17. Kim SS, Frimpong JA, Rivers PA, Kronenfeld JJ.

Effects of maternal and provider characteristics on up-to-date

immunization status of children aged 19 to 35 months. Am J Public Health.

2007;97:1-8.

|

|

|

|

|