|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2010;47: 709-718 |

|

Efficacy and Safety of Therapeutic Nutrition

Products for Home Based Therapeutic Nutrition for Severe Acute

Malnutrition: A Systematic Review |

|

Tarun Gera

From the Department of Pediatrics, Fortis Hospital,

Shalimar Bagh, New Delhi, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Tarun Gera, B-256, Derawala

Nagar, Delhi 110 009, India.

Email: [email protected]

|

|

Abstract

Context: Severe acute malnutrition (SAM) in

children is a significant public health problem in India with associated

increased morbidity and mortality. The current WHO recommendations on

management of SAM are based on facility based treatment. Given the large

number of children with SAM in India and the involved costs to the

care-provider as well as the care-seeker, incorporation of alternative

strategies like home based management of uncomplicated SAM is important.

The present review assesses (a) the efficacy and safety of home

based management of SAM using ‘therapeutic nutrition products’ or ready

to use therapeutic foods (RUTF); and (b) efficacy of these

products in comparison with F-100 and home-based diet.

Evidence Acquisition: Electronic database

(Pubmed and Cochrane Controlled Trials Register) were scanned using

keywords ‘severe malnutrition’, ‘therapy’, ‘diet’, ‘ready to use foods’

and ‘RUTF’. Bibliographics of identified articles, reviews and books

were scanned. The information was extracted from the identified papers

and graded according to the CEBM guidelines.

Results: Eighteen published papers (2 systematic

reviews, 7 controlled trials, 7 observational trials and 2 consensus

statements) were identified. Systematic reviews and RCTs showed RUTF to

be at least as efficacious as F-100 in increasing weight (WMD=3.0

g/kg/day; 95% CI -1.70, 7.70) and more effective in comparison to home

based dietary therapies. Locally made RUTFs were as effective as

imported RUTFs (WMD=0.07 g/kg/d; 95% CI=-0.15, 0.29). Data from

observational studies showed the energy intake with RUTF to be

comparable to F-100. The pooled recovery rate, mortality and default in

treatment with RUTF was 88.3%, 0.7% and 3.6%, respectively with a mean

weight gain of 3.2 g/kg/day. The two consensus statements supported the

use of RUTF for home based management of uncomplicated SAM.

Conclusions: The use of therapeutic nutrition

products like RUTF for home based management of uncomplicated SAM

appears to be safe and efficacious. However, most of the evidence on

this promising strategy has emerged from observational studies conducted

in emergency settings in Africa. There is need to generate more robust

evidence, design similar products locally and establish their efficacy

and cost-effectiveness in a ‘non-emergency’ setting, particularly in the

Indian context.

Key words: Efficacy, Management, Severe acute malnutrition,

Therapeutic nutrition product.

|

|

Despite praiseworthy advances in economic

prosperity and in the field of medical therapeutics, malnutrition

continues to be a significant public health problem in India.

Approximately 8.1 million children under the age of 5 years (6.4%) suffer

from severe acute malnutrition (SAM) and it is one of the important

co-morbidities leading to hospital admissions in our country(1). The

mortality associated with severe acute malnutrition is also high, ranging

from 73 to 187 per 1000(2). Needless to say, control and prevention of

severe acute malnutrition should be one of the important priorities of the

health planners. The current recommendations on the management of SAM by

WHO involve initial management at a referral centre for initial

stabilization followed by home therapy(3). Given the number of severely

malnourished children in India and the state of health infrastructure in

the country, particularly in the peripheries, these strategies do not seem

to be logistically feasible. Also, given the complex interplay between

social exclusion, poverty and SAM, inpatient treatment is associated with

un-acceptable costs to the family. In such a situation, uncomplicated

malnutrition is not considered a health problem by the family leading to

delayed institution of appropriate management. This leads to seeking of

health care when the problem is associated with other co-morbidities,

leading to increased mortality.

Given the grimness of the current situation, there is

clearly a need to improve and improvise the current standard guidelines

for the management of SAM in children. One of the suggested methods has

been the use of ‘therapeutic nutrition products’ administered at home to

children with uncomplicated SAM(4). A review was planned to study the

efficacy and safety of various therapeutic nutrition products for home

based management of SAM in children and to critically review the

extendibility of this strategy to India with the following objectives:

(a) to study the efficacy and safety of home

based management of SAM using ‘therapeutic nutrition products’ in

children; and

(b) to compare the efficacy of these products

with F-100 formaulation or home based dietary therapy.

Trials: Systematic Reviews; before and after

observational studies; Individual, cluster, and quasi randomized and

non-randomized controlled trials; consensus statements.

Participants: Children with severe acute

malnutrition.

Intervention: Therapeutic nutrition product,

basically derived from F-100 formulation, which is an integral part of the

WHO Management Protocol for SAM but should have these additional

properties: (i) does not need to be prepared in any form before

consumption; (ii) resists microbial contamination; and (iii)

can be stored at ambient temperature.

Control: No intervention or alternative

intervention such as home based dietary management or facility based

standard treatment.

Outcome Measures: For efficacy: (a)Recovery

rate (as defined by the authors); (b)Weight gain (g/kg/day); and (c)

Relapse.

For Safety: (a) Morbidities like diarrhea,

malaria and respiratory infections; and (b) Mortality.

Identification of studies: An exhaustive

literature search was done in the Cochrane Library and Pubmed using the

search terms ‘severe malnutrition’, ‘therapy’, ‘diet’, ‘ready to use

foods’ and ‘RUTF’ on April 20, 2010.

Review of Evidence

A total of 4073 citations were scanned to identify

relevant studies. The bibliography of identified articles was also scanned

and lateral search strategy in Pubmed was utilised to identify any

additional trials. A total of 18 published studies(4-21) were identified

and the information extracted was graded according to the CEBM

guidelines(22) and is presented in Table I. Wherever

possible and where the data from the published studies was extractable,

the data was pooled statistically to get a precise quantitative estimate.

The pooled estimates of the weighed mean difference (WMD) of the weight

gain between the control and intervention group and the mean pooled weight

gain in observational studies were calculated by meta-analyses using

random effects model assumptions with the "metan" command in STATA

software.

Table I

Role of Therapeutic Nutrition Products in Home Based Management of Severe Acute Malnutrition

in Children: Summary of Evidence

| Author, Year of Publication, Country,

Type of Study, Age, Inclusion Criteria |

Intervention, Sample Size, Duration of

Study |

Salient Findings |

Conclusion, Grade of Evidence |

| Systematic Reviews |

| Bhutta, et al., 2008(4), Pediatric age

group |

Intervention to reduce mother and child

undernutrition and survival; Analyzed data from 21 studies on

management of SAM |

The overall case-fatality rate in 23,

511 unselected severely malnourished children treated in 21

programs of community-based therapeutic care in Malawi, Ethiopia, and

Sudan, between 2001 and 2005,was 4·1%, with a recovery rate of 79·4%

and default of 11·0%. This compares favourably with case-fatality

rates that are typically achieved with facility-based management. |

Use of preprepared balanced foods such

as spreads and ready-to-use supplementary foods is feasible in

community settings.

Grade: 2a |

| Ashworth, et al., 2006(5), Systematic

Review, Malnourished children in non-emergency situations |

Community based rehabilitation for

treatment of severe malnutrition, Analyzed data from 33 studies

of community based rehabilitation |

Eleven (33%) programs were considered

effective. Of the subsample of programs reported since 1995, 8 of 13

(62%) were effective. None of the programs operating within routine

health systems without external assistance was effective. |

When done well, rehabilitation at home

with family foods is more cost-effective than inpatient care, but the

cost effectiveness of ready-to-use therapeutic foods (RUTF) versus

family foods has not been studied. Where children have access to a

functioning primary health-care system and can be monitored, the

rehabilitation phase of treatment of severe malnutrition should take

place in the community. Grade: 2a |

| Controlled Trials

RUTF versus Standard Practice |

Gaboulaud, et al., 2007; Niger(6), 6-59

mo; Inclusion: a) WHZ < -3 z or bilateral pitting edema

b) MUAC < 11cm |

Management at therapeutic feeding centre

(TFC) versus TFC and home based care versus home based care alone

using RUTF; Total: 1937 TFC: 660; TFC and home: 937; Home based: 340 |

(Order: TFC, TFC plus home, home)

Recovery: 52.7, 83.2 and 92.7; Mortality: 18.9, 0.0, 1.7; Default:

28.1, 16.8, 5.6 Transferred: 0.3, 0, 0; Wt gain: 20.8, 10.1, 9.7

g/kg/d |

Satisfactory treatment of SAM can be

achieved using a combination of home and hospital strategies. Children

without complications and preserved appetite may be directly managed

at home. Grade: 2b |

Ciliberto, et al. 2005; Malawi(7);

Quasi-randomized controlled trial; 10-60 mo; Inclusion

a) Moderate and Severe wasting and/or kwashiorkor

b) Absence of severe edema, evidence of systemic infection, or

anorexia |

RUTF versus standard practice (WHO

guidelines) at NRU;Total = 1178; RUTF:992; Standard Therapy: follow up

till 6 mo. |

Recovery (WFH z > -2): 79% versus 46%;

Mean wt. gain:3.5 g/kg/d versus 2.0 g/kg/d; Mortality and relapse:

8.7% versus 16.7%; Lower morbidity in RUTF group |

Home-based therapy with RUTF is

associated with better outcomes for childhood malnutrition than is

standard therapy Grade: 1b |

| Diop, et al., 2003; Senegal(8);

Randomized controlled trial; 6-36 months; Inclusion: WFH < -2z without

edema or after edema had resolved |

RUTF versus F-100 (received F-75 for 1-4

days prior to enrolment); Total: 70, RUTF: 35, F-100: 35 |

Wt gain: 10.1 g/kg/d in F-100 versus 15.6

g/kg/d in RUTF group, Mean duration to recovery: 17.3 days in F-100

versus 13.4 days in RTUF |

RTUF can be used efficiently for the

rehabilitation of severely malnourished children. Grade: 1b |

| Commercial or Indigenous

Medical Nutrition Products versus Home based Foods |

Manary, et al., 2004; Malawi(9);>12

months; Inclusion: a) Children discharged from NRU after initial

treatment of infectious and metabolic problems,

b) HIV negative c) Tolerated test dose of RUTF |

RUTF versus RUTF supplement versus

maize-soy flour; Total: 282, RUTF: 69 RUTF supplement: 96 Maize soy:

117

Duration: Till recovery/death/ infection |

Recovery: 95% in RUTF versus 78% in

others: Wt Gain: 7.0 versus 4.9 g/kg/d Morbidity: 3.8% diarrhea in

RUTF versus 5.6% in others |

Home based therapy of malnutrition with

RUTF is successful. Grade: 1b |

| Simpore, et al., 2006; Burkina Faso (10);

Randomized controlled trial; 6-60 months; Inclusion: Undernourished

children after initial stabilization using NG feeds |

Spirulina, Misola (made of Millet, soya,

peanut kernel, sugar, salt) versus traditional foods; Total: 550

Spirulina: 170, Misola: 170 Spirulina+Misola: 170, Control: 40 |

All groups showed significant wt gain;

maximum in spirulina and Misola group |

Rehabilitation by Spirulina plus Misola

seems synergically favour the nutrition rehabilitation better than the

simple addition of protein and energy intake. Grade: 1b |

| Local versus Imported

Therapeutic Nutrition Products |

| Sandige, et al., 2004; Malawi(11);

Quasi-randomized controlled trials: 1-5 years; Inclusion: a) Initial

stabilization at NRU; b) WHZ < -2z for non-hospitalized subjects |

Imported RUTF (Plumpy nut) versus locally

produced RUTF; Total: 260, Local RUTF: 135; Imported RUTF: 125;

Duration: 14 weeks |

Recovery: 78%, Recovery (Local): 80%,

Recovery (imported): 75%, Wt gain: 5.2 versus 4.8 g/kg/d, Default: 5%

Failure, mortality and relapse: 11% |

Home-based therapy with RUTF was

successful. Locally produced and imported RUTF have similar efficacy.

Grade: 1b |

| Diop, et al., 2004; Senegal(12);

Randomized controlled trial; 6-59 months; Inclusion: a) Severe

malnutrition (WFH <70% and/or edema); b) Initial stabilization for 7

days at facility |

Local RUTF versus Imported RUTF; Total:

61, Individual sample sizes not mentioned |

Mean energy intake comparable:

3434.2 vs 3181.2 kJ; Mean wt gain: 7.9 vs 8.1 g/kg/d; Mean

duration of rehabilitation: 35 vs 33 days |

Home-based rehabilitation with locally

made RUTF was successful in promoting catch-up growth. Locally

produced RTUF was, at least as well accepted as the imported

version and lead to similar weight gain. Grade: 1b |

| Cohort Studies |

| Amthor, et al., 2009; Malawi(13);

Prospective cohort study; Inclusion: a) WFH< 70% or Kwashiorkor b)

Good appetite |

RUTF to provide 175 kcal/kg/d and protein

5.3g/kg/d; N = 826 Duration: 8 weeks |

Recovery (WFH 100%): 93.7% Mean wt gain:

2.7 g/kg/d Default: 3.6% Relapse: Not Mentioned |

Home-based therapy with RUTF administered

by village health aides is effective in treating mal-nutrition during

food crises in areas lacking health services Grade: 2b |

| Jilcott, et al., 2010; Uganda(14);

Evaluation study of a feeding program; 6-59 months; Inclusion: a) WFA

<3rd percentile; b) MUAC < 12 cm |

Locally produced RUTF; N=20 Duration: 5

weeks |

Energy intake: 684 kcal/day Mean wt gain:

2.5 g/kg/day |

Locally-produced RUF is a promising

strategy for community-based care of malnourished children. |

| Linemann, et al., 2007;

Malawi(15);Prospective cohort study; 6-60 months; Inclusion: a)

Moderate and severe malnutrition b) Good appetite |

Locally produced RUTF; treatment by

medical professionals versus community health aides; Duration: 8 weeks |

Recovery: 89%; Mean wt gain: 3.5g/kg/d

Default: 7%; Mortality: 1.4%; No differences in recovery rate based on

training of the staff |

Home-based therapy with RUTF yields

acceptable results without requiring formally medically trained

personnel. Grade: 2b |

| Ciliberto, et al., 2006; Malawi(16);

Prospective cohort study;1-5 years;Inclusion: a) Edematous

malnutrition, b) Good appetite, c) No complications |

Administration of RUTF at home; Total:

219; Duration: 8 weeks |

Recovery: 83%, Mortality: 5%, Mean wt

gain: 2.8g/kg/d |

Children with edematous malnutrition and

good appetite may besuccessfully treated with home-based therapy.

Grade: 2b |

| Chaiken, et al., 2006; Ethiopia(17);

Prospective cohort study; Age not mentioned; Inclusion: a) WFH < 70%

or bilateral edemaor MUAC<11 cm |

RUTF; N=5799 Followed up till recovery |

Recovery (WFH 80%) : 66% Default:

2.3%,Transferred: 8.8% Mortality 0.2% |

Recovery rates comparable with

international standards, coverage far exceeded that of traditional

center-based care. Grade: 2b |

| Collins, et al., 2002; Ethiopia(18);

Retrospective Cohort Study;6-120 months; Inclusion: a) WFH< 70% or

bilateral pitting edema |

RUTF Oral antibioticVitamin A, FA

Education; N=170 Followed up till recovery |

Recovery: 85%, Mean wt gain: 3.2 g/kg/d

Mortality: 4%; Default: 5%, Relapse: 6%; Mean time to recovery: 42

days |

Outpatient treatment exceeded

internationally accepted minimum standards for recovery, default, and

mortality rates. Time spent in the program and rates of weight gain

were not satisfactory. Outpatient care could provide a complementary

treatment strategy to therapeutic feeding centres. Grade: 2b |

| Briend, et al., 1999; Chad(19);

Prospective Cohort study; >12 mo Inclusion: a) WFH < 70% b) Gaining wt

for 3 days |

Alternative F100 feeds were replaced by

RUTF; 203 meals |

Energy intake 40·2 (SD 20·9) kcal/kg per

feed for RUTF versus 20·2 (11·5) kcal/kg per feed for F100 (p<0·001);

Total mean energy intake for the day was same |

RUTF might be useful in contaminated

environments or where residential management is not possible. Grade:

2b |

|

Consensus Statements |

| WHO, UNICEF, SCN informal consultation on

community based management of SAM, 2006 (20) |

-

It is highly desirable to manage the treatment of

severely malnourished children with no complications at home without

an inpatient phase.

-

RUTFs are useful to treat severe malnutrition

without complications in communities with limited access to

appropriate local diets for nutritional rehabilitation.

-

When families have access to nutrient-dense

foods, severe malnutrition without complications can be managed in

the community without RUTF by carefully designed diets using

low-cost family foods, provided appropriate minerals and vitamins

are given.

-

Treatment of young children should include

support for breastfeeding and messages on appropriate feeding

practices for infants and young children. Children under 6 months of

age should not receive RUTF or solid family foods. These children

need milk-based diets, and their mothers need support to reestablish

breastfeeding. They should not be treated at home.

Grade of Evidence: 5 |

| National Workshop on Development of

Guidelines for Home Based Care and Standard Treatment of Children

suffering from Severe Acute Malnutrition, 2006(21) |

-

Home based management could be feasible,

acceptable, and cost effective option for those children categorized

as “uncomplicated”.

-

Experience indicates that home management of SAMN

is likely to be successful in closely monitored conditions with

protocols, motivated staff and parents. An effective home based care

and treatment program should be comprehensive and simultaneously

address nutritional, medical, social, and economical aspects.

-

Energy dense therapeutic diets with low bulk are

essential in the initial phase of management. However, these should

be economical, available, and acceptable. These diets could be (i)

home based (prepared/modified from the family pot) or (ii)

ready to use therapeutic food (RUTF). Feeding should be frequent (6

to 8 times per 24 hours), active, and hygienic.

-

Commercially available international RUTF may not

be suitable (acceptable, cost effective and sustainable) for Indian

settings.

-

Multiple micronutrient and mineral

supplementation should be provided orally as per the WHO guidelines

for inpatient management of SAMN children.

Grade of Evidence: 5 |

Systematic Reviews

A 2008 systematic review(4) on severe malnutrition

identified 276 articles on management of SAM, of which 21 were eventually

included in the final analyses. Of these, nine studies evaluated the

efficacy of WHO guidelines for facility based management of severe acute

malnutrition; pooled data from these trials showed a reduction in

mortality (Risk Ratio 0.45; 95% CI 0.32, 0.62). The authors could not

identify any randomized controlled trials studying the effect of RUTF on

mortality. However, obtaining the observational data collected from 21

field programs on 23,511 children on community based management of SAM,

the authors showed the case fatality rate to be 4.1%, recovery rate was

79.4% and default was 11%; figures which were noted to be comparable to

data from facility based trials. The authors also conducted two

meta-analyses of RCTs conducted in children recovering from SAM as part of

this review. The first one compared the use of RUTF with F-100, and

revealed an advantage of weight gain of 3.0 g/kg/day (WMD = 3.0; 95% CI=

–1.70, 7.70) in favour of RUTF; however, the results were not

statistically significant (P=0.21). Meta-analyses comparing RUTF

with maize/soy flour included only one study(9) and found significantly

increased weight gain (WMD= 2.10 g/kg/day; 95% CI= 1.97, 2.23; P<0.001).

Another review, conducted by Ashworth, et al.(5),

studied the effectiveness of rehabilitating severely malnourished children

in community settings. Effectiveness was defined as mortality of less than

5% or weight gain of more than 5 g/kg/day. 16 trials of home based

management of SAM children were identified; of these, seven were

considered to be effective. Amongst these, two programs were home based

programs where no food was distributed, while 5 trials utilised RUTF. The

authors noted that all successful programs aimed at providing the child

with high protein, high energy diet at frequent intervals. None of the

programs within the existing health systems was effective without external

assistance. Home based treatment with nutrition education was shown to be

effective in Bangladesh, even without the provision of RUTF or any other

food. However, this involved considerable effort in educating the mothers.

Controlled Trials

A total of seven controlled trials were identified.

Three trials compared home based management of RUTF with the standard

practise using F-100 formula at therapeutic centres. Of these, two studies

started home therapy after initial stabilization at a facility(6-8). A

previously conducted meta-analysis showed an advantage of weight gain of

3.0 g/kg/day (WMD = 3.0; 95% CI= –1.70, 7.70) in favour of RUTF against

F-100; however, the results were statistically not significant(4). The

third study(8) in this group followed a purposive selection method, where

more sick patients and those with complications were referred to a

facility; subjects without complications and with good appetite were

selected for home based management using RUTF. Expectedly, the mortality

in the F-100 group was much higher (18.9% versus 92.7%) because of the

unequal baseline status between the two groups.

Two studies were identified that compared the efficacy

of therapeutic nutrition products with traditionally available foods at

home. Manary, et al.(9) compared RUTF with maize soy flour and

observed higher weight gain and recovery, and lower morbidity in RUTF

group, in comparison to home based foods. The study had been included in

the systematic review mentioned above and details are given in that

section. The second study(10) used Misola (a local product made

from millet, soya, peanut kernal, sugar and salt) that supplies energy

almost equivalent to conventional RUTFs. The authors found that Misola

fortified with Spirulina led to higher weight gain, in comparison to

use of traditional foods.

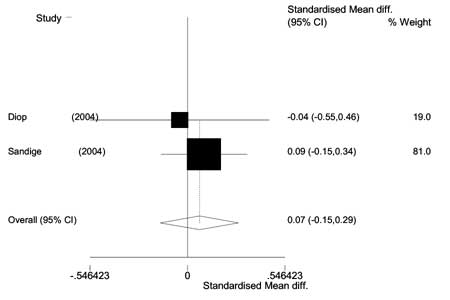

Two trials(11,12) compared the efficacy of a locally

made RUTF with imported RUTF. A meta-analysis was done from the data

derived from the two studies doing a comparative assessment of the impact

of locally made RUTF and imported RUTF. The pooled data from the two

studies done amongst 321 subjects, of whom 165 received locally made RUTF

and 156 received imported RUTF, showed no difference in the weight gain

between the two groups (WMD = 0.07 g/kg/d; 95% CI = -0.15, 0.29, 1.244,

P=0.15) (Fig 1).

|

|

Fig. 1 Forest Plot showing the

effectiveness of imported RUTF in comparison with local RUTF in

weight gain of severe malnourished children. |

Observational Trials

A total of 7 observational trials(13-19) were

identified. Of these, one trial(19) estimated the adequacy of energy

intake with ready to use foods in comparison to F-100 and found them to be

comparable. Most of the trials (4 out of 5) reported a recovery rate

(recovery variably defined by the authors) of more than 80%.

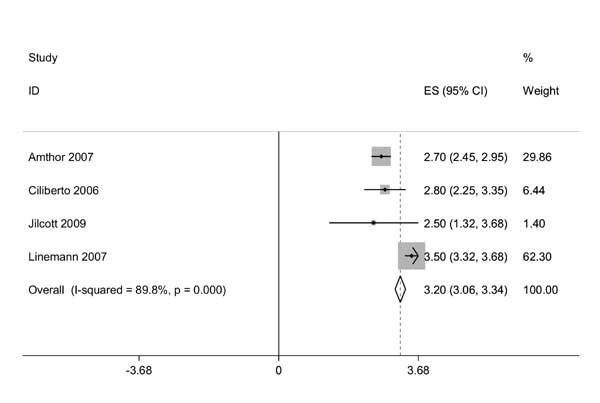

A pooled analysis of data from 5 studies (giving

information on 9145 severely malnourished children) reveals a recovery

rate of 88.3%, mortality of 0.7%, default rate of 3.6% and 6.7% babies had

failure of treatment or needed referral to a facility. Using meta-analytic

methods the pooled mean weight gain with the use of RUTF was 3.2 g/kg/day

(95% CI 3.06, 3.34 g/kg/d) (Fig 2). Of these trials, one(14)

used a locally designed RUTF and found weight gain comparable, as with the

use of commercially available RUTFs in other trials.

|

|

Fig. 2 Forest Plot showing the

pooled estimates for weight gain in severe malnourished children

using RUTF. |

Consensus Statements

Two consensus statements(20,21) were identified from

published literature. Both the statements emphasized the need to treat

uncomplicated severely malnourished children at home, and on the efficacy

of therapeutic nutrition products like RUTF for this purpose. They also

stated the need for micronutrient supplementation as per WHO guidelines,

exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months of life, monitoring of the

children to ensure compliance and adequate response to treatment and need

to develop local products to increase acceptability and decrease cost.

Discussion

Review of presently available published peer reviewed

literature shows that the use of ‘therapeutic nutrition products’ like

RUTF are efficacious in treating children with severe acute malnutrition,

who do not have any associated complications, and during the

rehabilitation phase when prolonged hospitalization may not be desirable.

Systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials on the topic show that

this modality of treatment may be as efficacious as standard (WHO)

treatment using F-100. Furthermore, these products are more effective than

home based foods with lower energy density in treating SAM. Locally

designed ready to use foods are as effective as the commercially available

products. The overall recovery rate with the use of RUTF is more than 85%

with a mortality of less than 1%.

However, the currently available level of evidence does

have some drawbacks that preclude the direct incorporation of such a

strategy into a program or a policy, and even its extendibility to India.

First is the fact that there is paucity of data, that too of robust

quality, available on the topic. Most of the information is available from

observational studies conducted in disaster situations, where no other

alternative strategy was feasible. The other noteworthy issue is the fact

that all the studies available so far were conducted in Africa. The

results of extending it to countries like India, in non-emergency

situations, with unknown efficacy and acceptability, are at present

unpredictable.

A number of studies, especially the controlled trials

which constitute a higher level of evidence are conducted in controlled

situations, under the supervision and monitoring of health care workers.

No doubt, this enables early identification of complications and

institution of early treatment, wherever indicated but digresses from the

basic rationale of using this strategy in areas where the health

infrastructure is poor or non-existent. Such supervised management also

increases the cost of management of SAM children. Based on the cost of

RUTF alone, Ashworth, et al.(5) estimated the cost to rehabilitate

a SAM child to be $55; for a HIV positive child it would double to $110.

To put it in perspective, in 2006, the per capita health care cost spent

by India was $39(23). These are substantial costs for the health system of

any developing country to absorb and emphasize the need for product

innovation at a local level.

The use of home treatment, using medical nutrition

products, as a public health strategy, therefore, should be treated as a

possibility in infancy, with its need to study its feasibility and cost

effectiveness in the Indian setting in an operational research format,

before suggesting its integration into the current health programs. The

effectiveness of cheaper locally designed ready to use foods is

encouraging, and should stimulate the scientific community to design

appropriate food(s) which are culturally acceptable in various parts of

our large country, as well as cost-effective.

Most important is the need to communicate to the policy

planners the urgency to address the problem of severe acute malnutrition.

Despite the fact that severe malnutrition is often a co-morbidity in large

proportion of avoidable child mortality, it does not get the attention it

deserves. It should be emphasized that the treatment of SAM is cost

effective – in fact, even hospital based management of SAM is more cost

effective in reducing mortality than many other child survival

intervention programs including the extremely visible vitamin A

supplementation program(24,25). The availability of alternative strategies

like home based management using locally made therapeutic nutrition

products is likely to add to the cost effectiveness. India needs

multi-pronged strategies to address the problem of severe malnutrition,

given the geo-graphic, cultural and financial barriers that exist across

this large country; home based management is likely to be one of them.

Funding: None.

Competing Interests: None stated.

|

EURECA Conclusion in the Indian Context

•

The presently available evidence, drawn from limited number of

studies, all conducted in Africa, on home based management of

severe acute malnutrition using therapeutic nutrition products

suggests that it is safe and efficacious.

•

There is need for further

research, particularly in product innovation and operational

issues to establish its efficacy and cost effectiveness in the

Indian context.

|

References

1. International Institute for Population Sciences.

National Family Health Survey 3, 2005-2006. Mumbai, India: IIPS; 2006.

2. Pelletier DL. The relationship between child

anthropometry and mortality in developing countries: implications for

policy, programs and future research. J Nutr 1994; 124 (suppl):

2047S–2081S.

3. Collins S, Dent N, Binns P, Bahwere P, Sadler K, and

Hallam A. Management of severe acute malnutrition in children. Lancet

2006; 368: 1992-2000.

4. Bhutta ZA, Ahmed T, Black RE, Cousens S, Dewey K,

et al. What works? Interventions for maternal and child undernutrition

and survival. Lancet 2008; 371: 417-440.

5. Ashworth A. Efficacy and effectiveness of

community-based treatment of severe malnutrition. Food Nutr Bull 2006 Sep;

27(3 Suppl): S24-48.

6. Gaboulaud V, Dan-Bouzoua N, Brasher C, Fedida G,

Gergonne B, Brown V. Could nutritional rehabilitation at home complement

or replace centre-based therapeutic feeding programmes for severe

malnutrition?J Trop Pediatr 2007; 53: 49-51.

7. Ciliberto MA, Sandige H, Ndekha MJ, Ashorn P,Briend

A, et al. Comparison of home-based therapy with ready-to-use

therapeutic food with standard therapy in the treatment of malnourished

Malawian children: a controlled, clinical effectiveness trial. Am J Clin

Nutr 2005; 81: 864 -870.

8. Diop EHI, Dossou NI, Ndour MM, Briend A, Wade S.

Comparison of the efficacy of a solid ready-to-use food and a liquid,

milk-based diet for the rehabilitation of severely malnourished children:

a randomized trial. Am. J. Clin, Nutr. 78: 302-307.

9. Manary MJ, Ndkeha MJ, Ashorn P, Maleta K, Briend A.

Home based therapy for severe malnutrition with ready to use food. Arch.

Dis. Child. 2004;89;557-561.

10. Simpore J, Kabore F, Zongo F, Dansou D, Bere A,

Pignatelli S, et al. Nutrition rehabilitation of undernourished

children utilizing Spiruline and Misola. Nutr J. 2006 Jan 23; 5: 3.

11. Sandige H, Ndekha MJ, Briend A, Ashorn P, Manary MJ.

Home-based treatment of malnourished malawian children with locally

produced or imported ready-to-use food. JPGN 2004; 39: 141–146.

12. Diop EI, Dossou N, Briend A, Yaya NA, Ndour MM,

Wade S. Home-based rehabilitation for severely malnourished children using

locally made ready-to-use therapeutic food (RTUF). Pediatr

Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition: Second World Congress, Paris,

France, 2004.

13. Amthor RE, Cole SM, Manary MJ. The use of home

based therapy with ready to use therapeutic food to treat malnutrition in

a rural area during a food crisis. J Am Diet Assoc 2009; 109: 464-467.

14. Jilcott SB, Ickes SB, Ammerman AS, Myhre JA.

Iterative design, implementation and evaluation of a supplemental feeding

program for underweight children ages 6-59 months in Western Uganda.

Matern Child Health J. 2010; 14: 299-306.

15. Linemann Z, Matilsky D, Ndekha M, Manary M, Maleta

K, Manary MJ. A large scale operational of home based therapy with ready

to use therapeutic food in childhood malnutrition in Malawi. Mat Child

Nutr 2007; 3: 206-215.

16. Ciliberto MA, Manary MJ, Ndekha MJ, Briend A,

Ashorn P. Home-based therapy for oedematous malnutrition with ready-to-use

therapeutic food. Acta Paediatr. 2006; 95: 1012-1015.

17. Chaiken MS, Deconinck H, Degefie T. The promise of

a community-based approach to managing severe malnutrition: A case study

from Ethiopia. Food Nutr Bull 2006 Jun; 27: 95-104.

18. Collins S, Sadler K. Outpatient care for severely

malnourished children in emergency relief programmes: a retrospective

cohort study. Lancet. 2002; 360 : 1824-1830.

19. Briend A, Lacsala R, Prudhon C, Mounier B, Grellety

Y, Golden MHN. Ready-to-use therapeutic food for treatment of marasmus.

Lancet 1999; 353: 1767-1768.

20. Prudhon C, Prinzo ZW, Briend A, Daelmans BMEG,

Mason JB. Proceedings of the WHO, UNICEF, and SCN Informal Consultation on

Community-Based Management of Severe Malnutrition in Children. Food Nutr

Bull 2006; 27(Suppl 3): S99-S108.

21. National Workshop on "Development of Guidelines for

Effective Home Based Care and Treatment of Children Suffering from Severe

Acute Malnutrition" Indian Pediatr 2006; 43: 131-139.

22. CEBM Centre for Evidence Based Medicine. Oxford

Centre for Evidence Based Medicine – Levels of Medicine (March 2009).

Available at: http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=1025. Accessed on May 15,

2010.

23. WHO Statistical Information System. Available at:

http://apps.who.int/whosis/data/Search.jsp. Accessed on May 18 th,

2010.

24. Jha P, Bangoura O, Ranson K. The cost-eff

ectiveness of forty health interventions in Guinea. Health Policy Plan

1998; 13: 249-262.

25. Tectonidis M. Crisis in Niger-outpatient care for severe acute

malnutrition. N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 224-227.

|

|

|

|

|