|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2010;47: 694-701 |

|

Home-based Rehabilitation of Severely

Malnourished Children in Resource Poor Setting |

|

Deepak Patel, Piyush Gupta, Dheeraj Shah and Kamlesh Sethi*

From the Departments of Pediatrics and *Dietitics,University

College of Medical Sciences (University of Delhi) and

Guru Teg Bahadur Hospital, Dilshad Garden, Delhi 110 095, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Dheeraj Shah, Associate Professor,

Department of Pediatrics, University College of Medical Sciences and

associated GTB Hospital, Dilshad Garden, Delhi 110 095, India.

Email: [email protected]

|

|

Abstract

Objective: To evaluate the feasibility and

outcome of home-based rehabilitation of severely malnourished children.

Design: Prospective and observational.

Setting: Rehabilitation at home (16 weeks)

following initial assessment or/and stabilization at hospital.

Participants: Thirty-four severely malnourished

(weight for length <70% of WHO reference) children between the ages of 6

months to 5 years.

Intervention: Initial assessment of the patient

was done in hospital. Those with complications or loss of appetite were

admitted in hospital and managed as per WHO guidelines. After discharge,

they were managed at home using home based diets. Those without

complications and with preserved appetite were directly eligible for

home-based rehabilitation. Follow up was done in hospital up to 16

weeks. Dietary intake, anthropometry and morbidities were recorded

during follow-up.

Results: Of the enrolled 34 children, 19 children

were admitted in hospital and 15 children were sent home after initial

assessment in hospital. Five did not clear the initial stabilization

phase (2 died, 3 left hospital). Finally 29 children qualified for home

based rehabilitation out of which 26 completed 16 week follow-up. During

the home based management phase, the reported mean (±SD) calorie intake

increased from 100 (±5) kcal/kg/d at entry point to 243 (±13) kcal/kg/d

at 16 weeks (P=0.000). Similarly, reported protein intake

increased from 1.1 (±0.3) g/kg/d to 4.8 (±0.3) g/kg/d (P=0.000).

During hospital stay (n=19), children had weight gain of 9.0

(±5.3) g/kg/d, while during home based follow up (n=29), weight

gain was 3.2 (±1.5) g/kg/d only. During home based rehabilitation, only

3 (11.5%) children had weight gain of more than 5 g/kg/d by the end of

16 weeks. Weight for height percent increased from an average (±SD) of

62.9% (±6.0%) to 80.3% (±5.7%) after the completion of 16 weeks (P=0.000).

Thirteen (45%) children recovered completely from malnutrition achieving

a weight for length of >80% whereas 15 (51.7%) recovered partly

achieving weight for length >70%. There was no death during the home

stabilization.

Conclusion: Home based management using home

prepared food and hospital based follow up is associated with

sub-optimal and slower recovery.

Key words: Community health services, Nutritional support,

Protein energy malnutrition.

|

|

To rationalize the management of severely

malnourished children, World Health Organization (WHO) proposed guidelines

which state that a child with complications should be treated in hospital

until the weight for length improves above 90%(1,2). However, this is

seldom feasible because of bed shortage in hospitals and budgetary

constraints. Prolonged hospital stay also carries the risk of nosocomial

infections leading to increased mortality. Admission of all children with

severe malnutrition is thus not operationally feasible, and hence

home-based management is an unavoidable alternative for a significant

proportion of these subjects. Preliminary evidence from Bangladesh and

Africa suggests that this alternative may be acceptable, cost-effective,

and reduce morbidity and mortality(3-8). In a recent statement, WHO

suggested that uncomplicated forms of severe acute malnutrition can be

treated in the community with ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF) or

therapeutic diets using locally available nutrient dense foods under

careful monitoring until they have gained adequate weight(9). However, the

guidelines regarding early discharge from the hospital followed by home

based management are lacking. The studies evaluating outcome of those

discharged early from the hospital or those managed at home are scarce.

The present study was thus conducted to evaluate the outcome and

feasibility of home based rehabilitation of severely malnourished

children. We hypothesized that it is possible to attain recovery and

reduce mortality with home based rehabilitation.

Methods

The study was conducted between November 2006 to

February 2008 in a prospective and observational manner. The setting was a

tertiary care hospital in Delhi, North India. The hospital predominantly

caters to poor urban population living in resettlement colonies and slums,

and also rural families from neighbouring state of Uttar Pradesh. The

study protocol was approved by Institutional Research Board, including

ethical clearance. The study procedure was fully explained to the

parents/caregivers, and informed written consent was obtained from the

primary caregiver.

Inclusion criteria

All consecutive children (6 months to 5 years) with

severe malnutrition presenting to the Pediatric out-patient department (OPD)

or emergency of hospital were eligible for inclusion. Severe malnutrition

was defined as weight for height (or length) <70% of median(2). WHO

multicentric growth standards were used as reference criteria(10).

Children were eligible for home management if: (i)

mother or caretaker was not full-time employed, (ii) family was

residing within 5 km of hospital premises, (iii) mother or

caretaker was trainable to provide home-based diet, and (iv)

family was financially able to provide the recommended home-based diet.

Children having other diseases incriminated as cause of severe

malnutrition, including cerebral palsy, congenital heart disorders,

hemolytic anemia, malignancies, known metabolic disorders, known

malabsorption syndromes, chromosomal malformations, or chronic renal and

hepatic disorders, were excluded.

Baseline data collected included demographic details

and presence of associated symptoms, including fever, vomiting or

diarrhea. Occupation, education and monthly income of parents were

recorded and a socio-economic status was assigned based on revised

Kuppuswamy classification(11). General hygiene of the household was

assessed in terms of source of drinking water, water storage practices,

and practice of hand washing. Clinical examination included anthropometry

(weight, length, mid-arm circumference, chest circumference and head

circumference), general physical examination and systemic examination. The

weight was recorded in the nude on an electronic weighing scale (Goldtech,

India) to the nearest 5 g. Length was recorded using an infantometer, and

head, chest and mid-upper arm circumference were recorded using non-strechable

measuring tape using standard techniques(12). The same observer recorded

all the measurements. Venous blood was drawn for estimation of hemoglobin,

blood sugar, albumin and serum electrolytes. Cultures of the blood, and

urine were taken. Chest X-ray and other relevant investigations

were done as and when required.

Assessment and Management

Initial assessment of the patient was done in hospital.

Those with complications or loss of appetite were admitted in hospital and

managed as per WHO guidelines as adapted by Indian Academy of Pediatrics (IAP)(3).

After discharge, they were managed at home using home based diets. Those

without complications and with preserved appetite were directly eligible

for home-based rehabilitation after initial assessment in hospital.

Initiation of cautious feeding: Feeding was started

with starter F-75 made at hospital kitchen using whole milk, sugar, oil

and water as per recommended formula(1). As no mineral mix or

micronutrient mix was available, potassium, magnesium and zinc were given

separately as described above. Initially enough starter was given to

provide 100 kcal/kg/day and 1-1.5 g protein/kg/day with 130 mL/kg/day of

fluid (when the child had severe edema 100 mL/kg/day was given).

Breastfeeding was continued as usual wherever possible. Initially, the

child was given feed more frequently with low volume, then gradually

frequency of feeds was decreased and volume per feed was increased. As the

patient started to regain appetite, the starter feed was changed with

home-made food. Mother was counseled to provide type, frequency and

quantity of food. Monitoring for amount of feed offered and left over,

frequency of vomiting and watery stool were done.

Discharge: Child was considered for

discharge when (i) the appetite had returned (easily consuming more

than 80% of recommended feeds orally), (ii) child had started

gaining weight (gain of at least 5 g/kg/day for 3 consecutive days), (iii)

immunization had been initiated, (iv) all acute complications had

been treated, (v) micronutrient supplementation was initiated, and

(vi) mother had been counseled for home-based care(13).

Home-Based Rehabilitation

All children directly enrolled for home-based

rehabilitation and those discharged from hospital were eligible for

home-based rehabilitation.

Nutritional support: Home based foods were advised

to provide 150 kcal/kg/day and 2-3 g/kg/day of proteins. A diet chart was

provided using home-based energy dense foods like besan-panjiri,

khichdi, parantha enriching them with jaggery and oil.

Energy dense feeding was gradually increased so as to provide

approximately 150-220 kcal/kg/day and proteins 4-5 g/kg/day. Mother was

given advice about type of food, quantity of food, and feeding frequency.

No external support for procuring or making food was provided to the

families. Daily multivitamin supplement was continued till 16 weeks.

Sensory stimulation and emotional support: Mother

was counseled to give tender loving care to the child and to provide

cheerful stimulating environment. Child was provided with toys as a part

of structured play therapy. Toys like ring on a string, rattle and drum,

in and out toy with blocks, posting bottle and doll were given.

Follow-up

Frequency of follow-up visits were: (i) 2

contacts/week separated by at least 48 hours in first two weeks, (ii)

once a week for 3-8 weeks, (iii) and from 8 weeks till 16 weeks,

every 4 weeks. At each visit, dietary intake was recorded by

recall-method, and detailed general physical and systemic examination was

done. Mother was recounselled about type, quantity and frequency of food

to be given. Any medical problem identified during visits was treated.

Measurement of weight, length, head circumference, chest-circumference and

mid-arm circumference was done at each visit. Investigations of all

children were repeated at 4 weeks and at 16 weeks. The child was stated to

have recovered completely if child achieved weight for length >80% at the

end of 16 weeks. The child was stated to be partially recovered if

the weight for length remained between 70% to 80% after 16 weeks of

follow-up. A weight gain of >5g/kg/d was defined as an acceptable weight

gain(1,2).

Statistical analysis: Descriptive analysis was

carried out for most outcomes. Calorie intake, protein intake, weight and

weight-for-height percent at 16 weeks were compared from baseline by

paired t test. Data were analyzed using SPSS 12.0 software.

Results

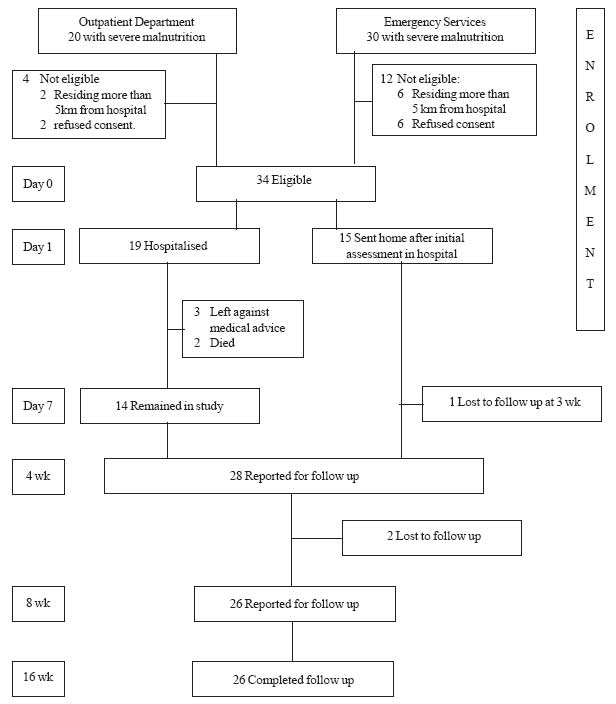

34 severely malnourished children formed the subjects

for present study (Fig 1). 41% children were less

than 1 year of age, and 62% were females. Of 34 children, only 3 (8.8%)

were completely immunized, only 5 (14%) children were exclusively

breastfed for 6 months, and around two-third were bottle-fed. Nearly half

(53%) had access to safe water supply and two-thirds (64%) had facility of

separate toilet. Anthropometry of study subjects at presentation (n=34)

is given in Table I. At first assessment, all

children were anemic (Hb <11 g/dL). Thrombocytopenia (platelet count <150

× 10 9 /L) was observed in 6 (17.6%),

hypoglycemia in 3 (8.9%), hyponatremia (Na+ <130 mEq/L) in 4 (11.8%),

hypernatremia (Na+ >150 mEq/L) in 7 (21%), hypokalemia (K+ <3.5 mEq/L) in

11 (32%), and hyperkalemia in (K+ >5.5 mEq/L) 4 (11.8%) children. Blood

culture at presentation was positive in 7 (21%) children, urine culture

was positive in 2 (5.9%), and stool demonstrated ova/cyst in 3 (8.8%)

children. At 16 weeks, hematological, biochemical and microbiological

profile was normal in all children.

|

|

Fig. 1 Study flow chart.

|

TABLE I

Baseline Characteristics and Anthropometry of Study Subjects at Presentation

|

Characteristics |

Admitted (n=19) |

Directly Recruited (n=15) |

Total (n=34) |

| |

mean (SD) |

mean (SD) |

mean (SD) |

| Age (mo) |

18.7 (10.0) |

21.9 (14.4) |

20.1 (12.1) |

| Males (%) |

8 (42.1) |

5 (33.3) |

13 (38.2) |

| Weight (kg) |

5.2 (1.3) |

5.1 (1.6) |

5.1 (1.4) |

| Weight for age (%) |

47.5 (7.2) |

48.1 (7.5) |

47.9 (7.4) |

| Length (cm) |

70.3 (7.4) |

69 (9.9) |

69.7 (8.4) |

| Length for age (%) |

85.9 (6.2) |

85.1 (5.9) |

85.5 (6.1) |

| Weight for length (%) |

62.5 (6.4) |

65 (3.8) |

63.7 (5.5) |

| Chest circumference (cm) |

39.7 (3.7) |

40.1 (4.1) |

39.8 (3.8) |

| Mid-arm circumference (cm) |

9.3 (1.2) |

9.3 (0.9) |

9.3 (1) |

Of 34 patients, 19 were admitted and treated in

hospital. The mean (±SD) duration of hospitalization was 5.4 (±2.2) days

(median: 6 d; IQR: 4-7 d). Two children had edema during presentation,

which settled on day 5 and 8 of admission. Two children died during

hospital stay and another 3 children left against medical advice. Thus

fourteen children thus were finally discharged. Fifteen children were not

hospitalized and sent home after initial assessment in hospital. These 29

children were eligible for home based rehabilitation. Of these, 26

children completed the follow up (Fig.1).

Dietary intake : The mean calorie and protein

intake of study subjects who completed 16 weeks follow-up (N=26) at

enrolment, day 3, day 7, 3 week, 6 week, 12 week and 16 week is shown in

Table II. During the home based management phase, the mean

(±SD) calorie intake increased from 100 (±5) kcal/kg/d at enrolment to 243

(±13) kcal/kg/d at 16 weeks (P<0.001). Similarly, protein intake

increased from 1.1 (±0.3) g/kg/d to 4.8 (±0.3) g/kg/d (P<0.001).

TABLE II

Changes in Calories and Protein Intake, Weight, and Weight for Length During Follow Up (N=26)

| Days of

enrolment |

Calories (kcal/kg/day) |

Protein (g/kg/day) |

Weight (kg) |

Weight

for height/length |

| Baseline

|

100.0 (5.0) |

1.1 (0.3) |

4.97 (1.4) |

62.9

(6.0) |

| 3 days |

117.3 (4.5) |

1.3 (0.2) |

5.07 (1.4) |

64.2

(5.8) |

| 7 days |

140.0 (13.2) |

1.6 (0.2) |

5.20 (1.4) |

65.6

(5.6) |

| 3 week |

161.5 (17.8) |

2.4 (0.3) |

5.45 (1.4) |

68.7

(5.6) |

| 6 weeks |

184.6 (18.1) |

3.3 (0.2) |

5.79 (1.4) |

72.7

(5.7) |

| 12 weeks |

225.2 (20.6) |

4.4 (0.4) |

6.36 (1.4) |

77.1

(4.8) |

| 16 weeks |

242.8* (13.1) |

4.8* (0.3) |

6.70* (1.5) |

80.3*

(5.7) |

*Significantly (P<0.001) higher than baseline values by paired t test. Values represent mean (SD).

|

Anthropometry: The mean (±SD) weight (kg) and

weight for length (%) of study subjects at enrolment, day 3, day 7, week

3, week 6, week 12 and week 16 is also shown in Table II.

Weight gain during hospital stay was 9.0 (±5.3) g/kg/d, while during

home-based rehabilitation, average weight gain was 3.2 (±1.5) g/kg/d.

During home based rehabilitation, only 3 (11.5%) children achieved weight

gain of more than 5 g/kg/d, while 26 (89.5%) children had weight gain of

less than 5 g/kg/d.

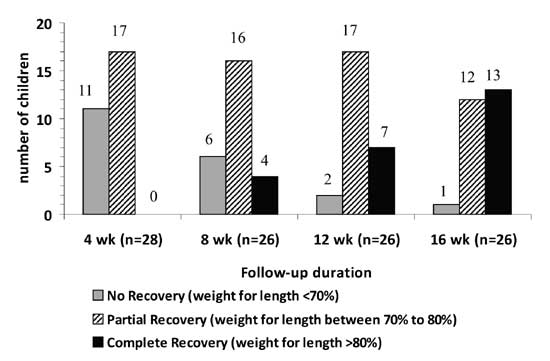

The recovery was complete in 13 (44.8%) children. Of

these, 2 children achieved

³80%

weight for length at 6 weeks, 1 child at 7 weeks, 1 child at 8 weeks, 3 at

12 weeks and 6 children at 16 weeks follow-up. The mean (±SD) weight for

length in these children at 16 weeks was 85% (±3.9%). The mean (±SD) time

needed to achieve 80% weight for length was 12 (±3) weeks. Of those who

recovered completely, 4 children went up to achieve >90% of weight for

length by the end of 16 week follow-up. Partial recovery occurred

in 15/29 (51.7%) children who achieved weight for length of between

70-80%. One child (3.5%) continued to have severe malnutrition even after

16 weeks. Fig. 2 compares the number of children with

% weight for length (<70%, 70-80%, >80%) at 4, 8, 12, and 16 weeks of

follow up.

|

|

Fig.2 Number of children achieving complete

or partial recovery during follow-up. |

Three children were lost to follow-up (1 at 3 weeks,

and 2 at 4 weeks). However, all these 3 children had crossed the 70%

weight for length barrier before opting out of the study, and thus were

classified as having partial recovery.

Discussion

The present study assessed the efficacy of home-based

rehabilitation after initial assessment or following discharge from a

hospital. We aimed to assess the outcome of home-based management using

home-based foods in real life situation as no external monetary support or

food was provided during this phase. No home visits were done. Using this

strategy, majority of children failed to achieve weight gain of more than

5 g/kg/d; the standard criteria for effectiveness as defined by WHO(1).

Also, less than half of children achieved >80% weight for length after

follow-up of 16 weeks. The mean weight gain during home based

rehabilitation was also less than weight gain during hospital stay.

The mean weight gain in our study (3.2 g/kg/d) was less

than that by Gaboulaud, et al. (3) (9.7 g/kg/d), Ashraf, et al.

(4) (6 g/kg/d), and Khanum, et al.(7) (4 g/kg/d). Also,

the mean duration for achieving weight for length >80% was more in our

study in comparison to earlier studies from Bangladesh(4,7). The reasons

for early recovery and more weight gain in former studies could be the

involvement of salaried health care workers from community in giving

proper training and advice. These workers had regular home visits, whereas

in our study, home visits during follow-up were not done. Non-availability

of ready to use therapeutic food (RUTF) and no external support to the

families in form of food or money could be a possible reason of inadequate

weight gain in our study. In our patients, weight gain was inadequate

during follow-up in most, despite history of consuming adequate calories

and proteins from home-based foods. This could be attributed to the poor

reliability of dietary recall method as well as lack of a mechanism of

monitoring their food preparation and techniques of feeding in our study.

It is possible that the foods were not sufficiently energy dense, and the

adequate numbers of feedings were not provided due to social constraints.

Linear programming analysis of diets from Africa and Bangladesh has

suggested that several home prepared diets for severely malnourished

children do not achieve the nutrient density required for successful

rehabilitation(14). Persistent infections were unlikely as we could not

find any such evidence during follow up, and no child on home-based

management died.

In a recent review by Ashworth(15), thirty-three

studies of community-based rehabilitation were examined and summarized for

the period of 1980-2005; eleven (33%) programs were considered effective.

The two indicators of effectiveness that were set for this review were

mortality <5% and weight gain

³5

g/kg/day. Of the sub-sample of programs reported since 1995, 8 of 13 (62%)

were effective. Most effective programs utilized RUTF or provided

mechanisms for procuring/preparing energy dense foods. None of the

programs operating within routine health systems without external

assistance was effective.

A potential limitation of our study was that we did not

evaluate the outcomes in a comparative manner, and thus the efficacy of

the management was not directly compared with hospital care or any other

effective approach. The sample size was also small to do any subgroup

analysis. The strength of our study was that it was done in realistic

scenario without actually providing the food or financial support. This

has important operational implications as most facilities managing

severely malnourished children in India currently do not provide

therapeutic nutrition, and only rely on nutritional advice/counseling.

We conclude that home-based management (directly or

following early discharge from hospital) using home prepared food and

hospital based follow up is associated with sub-optimal and slow recovery.

There should be effective monitoring system and mechanism for providing

energy dense foods/ RUTF to strengthen the community based management of

severely malnourished children. Effectiveness of community-based

rehabilitation may require careful planning and additional resources,

including nutrition educators. Provision of RUTF might help in

strengthening the implementation process but its cost, logistics of

procurement and distribution, sustainability, and consequences of

withdrawal would need to be carefully considered. Future research should

include comparative evaluation of different strategies in a controlled

manner and operational research to strengthen the existing home and

hospital based approaches.

Contributors: PG and DS conceptualized and

supervised the study. DP and KS collected the data and followed up the

patients. DP and KS prepared the initial draft of manuscript which was

revised by PG and DS. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None stated.

|

What is Already Known?

•

Home management of

uncomplicated severe malnutrition is a feasible option. Ready-to-use

therapeutic food (RUTF) is an effective option in controlled

settings.

What this Study Adds?

•

Home based

management using home prepared food and hospital based follow up is

associated with sub-optimal and slower recovery.

|

References

1. Ashworth A, Khanum S, Jackson A, Schofield C.

Guidelines for the Inpatient Treatment of Severely Malnourished Children.

Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003.

2. Bhatnagar S, Lodha R, Choudhary P, Sachdev HPS, Shah

N, Narayan S, et al. IAP Guidelines 2006 on Hospital based

Management of Severely Malnourished Children (adapted from WHO

guidelines). Indian Pediatr 2007; 44: 443- 461.

3. Gabouland V, Dan-Bouzoua N, Brasher G, Fedida G,

Gergonne B, BrownV. Could nutritional rehabilitation at home complement or

replace centre-based therapeutic feeding programmes for severe

malnutrition? J Trop Pediatr 2007; 53: 49-51.

4. Ashraf H, Ahmed T, Hossain MI, Alam NH, Mahmud R,

Kamal SM, et al. Day-care management of children with severe

malnutrition in an urban health clinic in Dhaka, Bangladesh. J Trop

Pediatr 2007; 53: 171-178.

5. Orach C, Kolsteren P. Outpatient care of severely

malnourished children. Lancet 2002; 360: 1800-1801.

6. Ashworth A, Khanum S. Cost effective treatment of

severely malnourished children: what is best approach? Health Policy Plan

1997; 12: 115-121.

7. Khanum S, Ashworth A, Hulty SR. Controlled trial of

three approaches to the treatment of severe malnutrition. Lancet 1994;

344: 1728-1732.

8. Bredow M, Jackson A. Community-based, effective, low

cost approach to the treatment of severe malnutrition in rural Jamaica.

Arch Dis Child 1994; 71: 297-303.

9. Community-Based Management Of Severe Acute

Malnutrition: A Joint Statement by the World Health Organization, the

World Food Programme, the United Nations System Standing Committee on

Nutrition and the United Nations Children’s Fund. World Health

Organization; 2007.

10. de Onis M, Garza C, Onyango AW, Martorell R. WHO

Child Growth Standards. Acta Paediatr 2006; 95 (Suppl 450): 1-104.

11. Mishra D, Singh HP. Kuppuswamy’s socio-economic

status scale: A revision. Indian J Pediatr 2003; 70: 273-274.

12. Physical Status: The Use and Interpretation of

Anthropometry- Report of a WHO Expert Committee. WHO Technical Report

Series; 854. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1995.

13. Gupta P, Shah D, Sachdev HPS, Kapil U. National

Workshop on Development of Guidelines for Effective Home Based Care and

Treatment of Children Suffering from Severe Acute Mal-nutrition. Indian

Pediatr 2006; 43: 131-139.

14. Ferguson EL, Briend A, Darmon N. Can optimal

combinations of local foods achieve the nutrient density of the F100

catch-up diet for severe malnutrition? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2008;

46: 447-452.

15. Ashworth A. Efficacy and effectiveness of

community-based treatment of severe malnutrition. Food Nutr Bull 2006;

27(3 Suppl): S24-S48.

|

|

|

|

|