|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2021;58:338-344 |

|

Catalytic Support for

Improving Clinical Care in Special Newborn Care Units (SNCU)

Through Composite SNCU Quality of Care Index (SQCI)

|

|

Harish Kumar, 1 Rajat

Khanna,2 Varun Alwadhi,3

Ashfaq Ahmed Bhat,2 Sutapa B

Neogi,4

Pradeep Choudhry2, Prasant

Kumar Saboth1 and Ajay Khera5

From 1VRIDDHI, IPE Global Ltd.; 2Norway India Partnership Initiative;

3Department of Pediatrics, Kalawati Saran Children’s Hospital;

4International Institute of Health Management Research; and

5Ministry of

Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; New Delhi, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Ashfaq Ahmed Bhat, Norway India Partnership

Initiative, New Delhi, India.

Email: [email protected]

Received: April 30, 2020;

Initial review: June 29, 2020;

Accepted: November 17, 2020.

|

Objective: To develop a composite index that

serves as a proxy marker of quality of clinical service and pilot test

its use in 11 special neonatal care units (SNCUs) across two states in

India.

Design: Secondary data from SNCU webportal.

Settings: Special new-born care units in

Rajasthan and Orissa.

Intervention: We developed a composite SNCU

Quality of care Index (SQCI) based on seven indices from SNCU online

database. These included rational admission index, index for rational

use of antibiotics, inborn birth asphyxia index, index for mortality in

normal weight babies, low birth weight admission index, low birth weight

survival index, and optimal bed utilization index.

Outcome: Based on the SQCI score, the performance

of SNCUs was labelled as good (SQCI 0.71- 1.0), satisfactory (SQCI 0.4-

0.7) or unsatisfactory (SQCI <0.4).

Results: The mean difference in SQCI between

Jan-Mar 2016 and 2017 was 0.20 (95% CI 0.13- 0.28; P<0.001).

Similar results were obtained for rational admission index, rational use

of antibiotics, mortality in normal weight babies, low birth weight

survival and optimal bed utilization. A significant improvement in the

overall composite score was noted in Odisha (Mean difference 0.22, 95%

CI 0.11-0.33, P=0.003) and Rajasthan (Mean difference 0.17, 95%

CI 0.05- 0.3, P=0.002). Conclusion: QI approach using SQCI

tool is a useful and replicable intervention. Preliminary results show

that it does lead to strengthening of implementation of the programs at

SNCUs based on the comprehensive scores generated as part of routine

system.

Keywords: District hospital, Health programs, Health system,

Quality improvement.

|

|

I

ndia has experienced a rapid expansion of

Facility Based Newborn Care (FBNC) at various levels in the

health system in the last decade. The services provided at each

level is a product of infrastructure, availability of skilled

manpower, capacity of the institution and referral mechanisms

available. The facilities have been classified as newborn care

corners (NBCC) at every point of child birth, newborn

stabilization units (NBSUs) at first referral units (FRUs) and

special newborn care units (SNCUs) at district hospitals [1].

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), Government of

India (GoI) under National Health Mission (NHM) has ensured

functional SNCUs, in most of the District Hospitals in the

country and has plans to further strengthen these units [2,3].

The SNCUs are equipped to manage small and

sick neonates except those who need mechanical ventilation and

surgical care. These units have admission and discharge criteria

for optimal utilization of services and bed strength and

services [4]. SNCUs have resulted in improvement in case

fatality among newborns admitted to hospitals [5]. However,

there are challenges in infrastructure, manpower and care

practices [6]. There is a need to assess the performance of

SNCUs with respect to quality of patient care, organization and

process to support improvement and enhance accountability

[5,7-9].

Experiences from QI programs on FBNC are also

limited [10-13]. Reports have uncovered the insuffi-ciencies of

data management systems to monitor key indicators. To address

this gap, GoI with support from UNICEF and Norway India

Partnership Initiative (NIPI) established a web-based data

management and tracking system, ‘SNCU online’ in the year 2011,

to be used across all the SNCUs in India. Between April, 2016

and March, 2017, SNCU online was functional in 571 SNCUs across

27 states with data available for more than 700,000 infants.

Measurement of quality of clinical services

rendered in the SNCUs is essential for feedback and improvement.

The objective of this study was to develop a composite index

that serves as a proxy marker of quality of clinical service and

pilot test its use in SNCUs in India.

METHODS

This study was conducted in two stages/phases

viz., development of a composite index (SNCU Quality of Care

Index or SQCI), and pilot testing the tool for feasibility and

applicability in SNCUs.

Development of SQCI: A team consisting of

six experts from national and state NIPI team developed a

comprehensive tool drawing relevant indicators from SNCU online

web portal. The process, spanning over a four month period,

involved field visits and observations by pediatricians and

statisticians. While defining the indices, due considerations

were given on whether those were in accordance with global norms

and standards for measuring quality of clinical care,

user-friendliness, access to available data, ability to do

self-assessment, and utility to Government for providing timely

feedback. The focus was to have a dynamic model that could

assess the optimal utilization of services, identify gaps in

skills and clinical practices that influence the case fatality

in every SNCU. For each of these objectives, most appropriate

indicators were identified and put into a statistical model to

arrive at a composite index. This was then piloted in one SNCU

to test for its reliability, feasibility and usefulness in

public health settings.

Initially, six indices were selected for

SQCI, which also included an index on total deaths in the SNCU.

Since this index was not able to measure the specific quality of

care issues in the SNCU, it was replaced with mortality in

normal weight babies ( ³2500

gram). Additionally, one more indicator was added on inborn

birth asphyxia index, to measure whether asphyxia was managed

adequately in the labour room, and its subsequent load and

implication on SNCUs in terms of bed occupation.

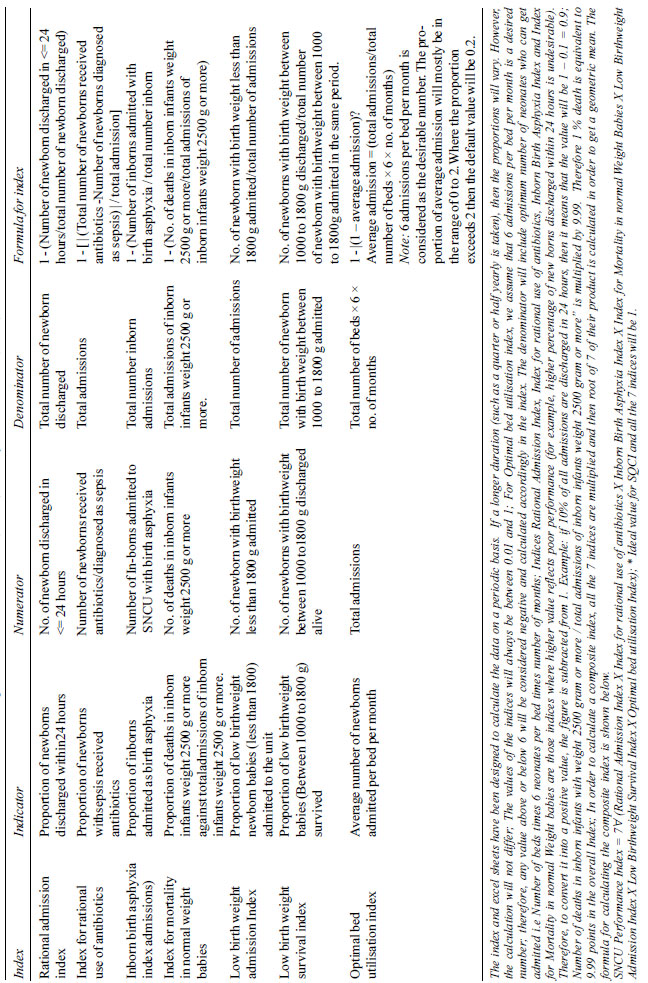

SQCI is a composite index of seven indices,

each having a range from 0.01 to 1 (Table I and

Web

Table I): rational admission index, index for rational use

of antibiotics, inborn birth asphyxia index, index for mortality

in normal weight babies, low birth weight admission index, low

birth weight survival index, optimal bed utilization index.

Since the indices are comparing different items and each item

has multiple properties, we have taken the geometric mean to

calculate the final score. Based on the SQCI score, the

performance of SNCUs was assessed as a Likert scale and labelled

as good (SQCI 0.71- 1.0), satisfactory (SQCI 0.4- 0.7) and

unsatisfactory (SQCI <0.4) [14].

|

Table I Special Newborn Care Unit

(SNCU) Quality of Care Index (SQCI) Calculations

|

|

Data collection: The SQCI tool was used

in the states of Rajasthan and Odisha. All the parameters were

retrieved in each quarter of the year, recorded in a predesigned

excel database and SQCI score calculated by the program team.

The indices were calculated for every month and then compiled

for each quarter of the year. Each index was color coded (red

for unsatisfactory, yellow for satisfactory and green for good)

for better understanding. No additional data were collected for

the purpose of the study.

Overall feedback, with particular emphasis on

the two worst indicators, was provided to the districts. This

facilitated improvement in the performance of the SNCUs.

Permission and approvals were obtained from

concerned authorities (MoHFW, State governments) for retrieval

and analysis of data from SNCU database. Anonymity and rights of

patients and doctors were respected and therefore we did not

consider individual level data in our analysis.

The data for SQCI computation was taken from

an ongoing program and hence no ethical issues were involved.

Since this was a program evaluation based on routinely collected

data, no additional data was collected.

Data of five quarters starting from Jan- Mar

2016 to Jan- Mar 2017 were compared to assess the change in the

quality of services. Paired t test was done to explore

the statistical significance of the difference over a period of

one year (from Jan-Mar, 2016 to Jan-Mar, 2017).

RESULTS

We present the results as composite scores

aggregated from the SNCUs for the two states. In the pilot

phase, data from 11 SNCUs out of total 92 SNCUs in the states of

Rajasthan (n=59) and Odisha (n=33) were analyzed.

The SQCI for Odisha increased from 0.44 to 0.57 over a period of

one year while that of Rajasthan showed a marginal increase. (Table

II, Fig. 1). Overall, the mean difference of the

differences in the composite index of each unit between January

to March, 2016 and same period in 2017 was 0.20 (95% CI 0.13-

0.28; P<0.001). Similar results were obtained for other

indices. A significant improvement in the overall composite

score was noted in Odisha [MD (95% CI) 0.22, (0.11-0.33) P=0.003]

and Rajasthan [MD (95% CI) 0.17, (0.05-0.3) P=0.002]

(data not shown).

We analyzed the key indices that are most

amenable to improvement within the limited period of

intervention. Those indices were index for rational use of

antibiotics, index for mortality in normal weight babies and low

birth weight survival index. An analysis of every unit for the

difference in these indices for the same time periods showed a

significant improvement. A positive effect in terms of an

improvement in the overall composite score was observed one year

after the initiation of the QI model (data available at

https://sncuindiaonline.org).

Table II Indices to Measure Quality of Care in SNCUs in India Based on SQCI Model

| Time period |

SQCI |

Rational |

Index for |

Inborn birth |

Index for |

Low birth |

Low birth |

Optimal |

|

|

admission |

rational use |

asphyxia |

mortality in |

weight |

weight |

bed |

|

|

index |

of antibiotics |

index |

normal weight |

admission |

survival |

utilization |

|

|

|

|

|

babies |

index |

index |

index |

| Odisha (7 SNCUs combined) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I qtr 2016 |

0.44 |

0.91 |

0.34 |

0.70 |

0.40 |

0.27 |

0.66 |

0.20 |

| II qtr 2016 |

0.28 |

0.95 |

0.01 |

0.64 |

0.44 |

0.26 |

0.71 |

0.28 |

| III qtr 2016 |

0.46 |

0.95 |

0.41 |

0.62 |

0.17 |

0.33 |

0.65 |

0.47 |

| IV qtr 2016 |

0.44 |

0.94 |

0.42 |

0.62 |

0.09 |

0.34 |

0.66 |

0.63 |

| I qtr 2017 |

0.57 |

0.99 |

0.50 |

0.69 |

0.36 |

0.27 |

0.81 |

0.74 |

| Rajasthan (4 SNCUs combined) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I qtr 2016 |

0.50 |

0.74 |

0.55 |

0.79 |

0.71 |

0.19 |

0.67 |

0.27 |

| II qtr 2016 |

0.40 |

0.76 |

0.11 |

0.90 |

0.87 |

0.18 |

0.71 |

0.20 |

| III qtr 2016 |

0.40 |

0.73 |

0.12 |

0.89 |

0.69 |

0.19 |

0.76 |

0.20 |

| IV qtr 2016 |

0.49 |

0.78 |

0.29 |

0.89 |

0.71 |

0.21 |

0.70 |

0.35 |

| I qtr 2017 |

0.52 |

0.80 |

0.51 |

0.82 |

0.67 |

0.20 |

0.62 |

0.39 |

| MD (95% CI) a |

0.20 |

0.07 |

0.28 |

-0.01 |

-0.33 |

0.008 |

0.01 |

0.14 |

|

(0.13-0.28)b |

(0.03-0.11)b |

(0.16-0.41)c |

(-0.05-0.03) |

(-0.52,-0.14)b |

(-0.02--0.03) |

(-0.09-0.12)b |

(0.007- 0.27)b |

| aMean difference in

scores in each unit in first quarter of 2016 and 2017;

bP<0.05; #P<0,001, SNCU: Special newborn care unit;

SQCU: SNCU quality of care index; ^I quarter:

January-March, II quarter: April-June, III quarter:

July-September, IV quarter: October-December. |

DISCUSSION

This study describes the development of a

composite index and its application in two states of India. Our

results showed SQCI in the SNCUs could be utilized for improving

quality of services. An analysis of the SQCI over a period of

one year showed a significant improvement in both the states.

Our findings demonstrate that program

managers can use the tool to monitor the FBNC program. In the

state of Rajasthan, the SQCI scores were utilized to initiate

discussions on the challenges and discuss areas for improvement

such as rational use of antibiotics, admission criteria and

inpatient management of LBW newborns. Similarly, in Odisha, this

model was used to identify and prioritize the shortfalls that

were addressed during supportive supervision by the medical

officers as part of the routine program.

Globally, it is now known that quality

improvement (QI) models work in diverse cultures and locations

[15]. Studies have shown that a regular system of QI

intervention generally leads to improved adherence to health

care delivery practices [8,12,13]. A QI project in six tertiary

care hospitals in India, focused on interventions for increasing

awareness on health care associated infections, improving

compliance to infection control measures and monitoring rational

antibiotic use reported. Periodic visits, rapid assessments and

feedback, training and action at public health facilities has

been reported to lead to improvement in adherence to QI

guidelines in labor rooms in Rajasthan [8]. Periodic monitoring

of labor rooms and newborn care facilities in Bihar also

resulted in favorable outcomes [13,17]. Though on-site real time

observations to assess quality of delivery of services have

their own merits, yet it is a cost-and-resource intensive

exercise and hence, may not be a preferred option for public

health program [13].

Several QI models that have attempted to

improve the quality of services have focused on babies with LBW

[18-21]. The goals of these models were to identify and explain

variations in clinical practices and patient outcomes from the

routinely collected secondary data on newborns weighing less

than 1500g [19]. Our assessment is based on the online database

maintained by the health system, which is similar to those

models. In our country, the purpose of setting up SNCUs was to

take care of LBW babies primarily. However, reports suggest that

the bulk of admissions to SNCUs are contributed by babies whose

birthweights are more than 2500 [5,6]. Our approach therefore

included babies of all birth weights.

An advantage of our approach is the ease with

which data can be assembled and analyzed without relying on any

special technical help. In our case, concurrently and routinely

collected data from SNCUs were used which was independent of the

process of medical records data abstraction. The indicators used

to calculate SQCI are objective in nature, and less likely to be

influenced by individual perceptions. Another advantage of our

approach is that every SNCU in-charge in the country has access

to review their own performance through the online portal, which

is an advantage in terms of efficiency and feasibility.

Our limitations were that we captured only

the providers’ performance and users’ perspectives were

completely missed out. Although an important component in itself

[22], we did not include them due to feasibility issues. Certain

indices such as newborns discharged within 24 hour do not

capture the reasons for admission, which is a drawback.

Secondly, an independent evaluation to assess the validity of

SQCI indices was not undertaken and it remains a limitation. In

order to obtain some feedback on the reliability of SQCI,

trained neonatologists did an independent assessment of select

SNCUs, although this was not very objectively done. The overall

feedback given by the experts confidentially corroborated well

with the inferences drawn based on data driven QI model. Our

experiences from 11 SNCUs across two states represent diverse

locations lending to a possible generalizability with states

with similar health indicators.

Government at both national and state levels

were in support of QI initiatives using SQCI. Use of an existing

mechanism of surveillance without any major external support for

QI makes it more feasible as compared to the existing QI models.

Implemented within the existing health systems, infrastructure

and human resources, it contains a few components that can be

easily added onto the existing system.

The SQCI index is a useful tool to evaluate

the quality of neonatal care services in the Indian Special

Newborn Care Units. The index can be used to follow a unit’s

performance over time or to benchmark various units and for

quality improvement.

Contributors: HK: conceptualized SQCI and

provided technical oversight of the process of SQCI analysis and

use; RK: developed the statistical model during

conceptualization of SQCI, analyzed data, interpreted the

results and contributed to writing of the manuscript. VA,AK:

provided technical support during conceptualization of SQCI,

monitoring indicators and reviewed the manuscript; AAB:

contributed in the framing of monitoring indicators and reviewed

the manuscript SBN: reviewed the literature and drafted the

manuscript; PC,PKS: implemented SQCI in their respective states,

reviewed manuscript and provided inputs.

Funding: This study was conducted as part

of the Newborn care project supported by Norway India

Partnership Initiative (NIPI); Competing interest: None

stated.

|

|

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN?

•

There are multiple methods available to assess

quality of services from routinely collected data.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS?

•

It is possible to calculate indices (SQCI) based on

available data that serve as proxy to quality of

services.

•

It is feasible to implement SQCI in public health

settings for quality improvement.

|

REFERENCES

1. Facility based newborn care:

Operational guidelines. In: Ministry of Health and Family

Welfare, editor. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family

Welfare, Government of India; 2011.

2. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare.

Health Management Information System. In: Ministry of

Health and Family Welfare, editor. Ministry of Health and Family

Welfare, Govt of India; 2017.

3. MOHFW. Special Newborn Care Units in

India. In: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, editor.

New Delhi 2017.

4. Strengthening Facility Based Paediatric

Care: Operational Guidelines for Planning & Implementation in

District Hospitals. In: Child Health Division, Ministry

of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, New Delhi.

September 2015. Accessed on November 16, 2020. Available from:

https://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/

programmes/child-health/guidelines/Strenghtening_FacilityBasedPaediatric

Care-OperationalGuidelines.pdf

5. Neogi SB, Malhotra S, Zodpey S, Mohan P.

Assessment of special care newborn units in India. Health Pop

Nutr. 2011;29:500-9.

6. Neogi SB, Malhotra S, Zodpey S, Mohan P.

Challenges in scaling up of special care newborn units-Lessons

from India. Indian Pediatr. 2011;48:931-5.

7. Sharma G, Powell-Jackson T, Haldar K,

Bradley J, Filippi V. Quality of routine essential care during

childbirth: Clinical observations of uncomplicated births in

Uttar Pradesh, India. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95:419-29.

8. Iyengar K, Jain M, Thomas S, et al.

Adherence to evidence based care practices for childbirth before

and after a quality improvement intervention in health

facilities of Rajasthan, India. BMC Pregn Childbirth.

2014;14:270.

9. Chauhan M, Sharma J, Negandhi P, Reddy S,

Sethy G, Neogi S. Assessment of newborn care corners in selected

public health facilities in Bihar. Indian J Public Health.

2016;60:341-6.

10. Chawla D, Suresh GK. Quality improvement

in neonatal care - A new paradigm for developing countries.

Indian J Pediatr. 2014;81:1367-72.

11. Neogi SB, Malhotra S, Zodpey S, Mohan P.

Does facility-based newborn care improve neonatal outcomes? A

review of evidence. Indian Pediatrics. 2012;49:651-58.

12. Sarin E, Kole SK, Patel R, et al.

Evaluation of a quality improvement intervention for obstetric

and neonatal care in selected public health facilities across

six states of India. BMC Pregn Childbirth. 2017;17:134.

13. Neogi SB, Shetty G, Ray S, Sadhukhan P,

Reddy SS. Setting up a quality assurance model for newborn care

to strengthen health system in Bihar, India. Indian Pediatr.

2014;51:136-8.

14. Vagias WM. Likert -type scale response

anchors. Clemson University: Department of Parks, Recreation and

Tourism Management, 2006.

15. Nadeem E, Olin SS, Hill LC, Hoagwood KE,

Horwitz SM. Understanding the components of quality improvement

collaboratives: a systematic literature review. Milbank Q.

2013;91:354-94.

16. Mehndiratta A. Quality Improvement of

Facility Based New Born Care in India: ACCESS health

International; 2014; Available from: http://accessh.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Quality-Improvement-of-Facility-Based-Newborn-Care-in-India-Poster.pdf

17. Sharma J, Neogi S, Negandhi P, Chauhan M,

Reddy S, Sethy G. Rollout of quality assurance interventions in

labor room in two districts of Bihar, India. Indian J Public

Hlth. 2016;60:323-8.

18. Horbar JD. The Vermont Oxford Network:

Evidence-based quality improvement for neonatology. Pediatrics.

1999;103:350-9.

19. Horbar JD, Rogowski J, Plsek PE, et al.

Collaborative quality improvement for neonatal intensive care.

NIC/Q Project Investigators of the Vermont Oxford Network.

Pediatrics. 2001;107:14-22.

20. Hernández-Borges AA, Pérez-Estévez E,

Jiménez-Sosa A, et al. Set of quality indicators of pediatric

intensive care in Spain: Delphi method selection. Pediatr Qual

Safety. 2017;2:e009.

21. Profit J, Zupancic JA, Gould JB, et al.

Correlation of neonatal intensive care unit performance across

multiple measures of quality of care. JAMA Pediatr.

2013;167:47-54.

22. Lachman P, Jayadev A, Rahi M. The case

for quality improvement in the neonatal intensive care unit.

Early Human Dev. 2014;90:719-23.

|

|

|

|

|