|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2020;57: 376-377 |

|

Infantile Beri Beri: The Mizoram Experience

|

|

John Malsawma

Department of

Pediatrics, Synod Hospital, Durtlang, Mizoram, India.

Email:

[email protected]

|

|

In the land where the bamboo flowers, and where the population is

just over 10 lakhs, is the small North-Eastern state of Mizoram, from

where we would like to share our experience with infantile beriberi and

how we handled it.

In the last couple of years, from the months

of August-September to around February-March, we used to get very sick

infants aged mostly 6 weeks to about 3 to 4 months of age. The babies

usually came with complaints of lethargy, drowsiness, groaning, poor

feeding, sometimes with high shrill cries and sometimes with rapid

breathing – fever was noticeably absent. Most were hospital-born with

uneventful birth history. Their mothers had regular antenatal checkups

and were receiving iron/ folic acid and calcium tablets till before and

after delivery. All the babies were on exclusive breast feed. These

babies were mainly from low socio-economic status families.

At

first, our line of treatment was on the lines of infection/sepsis. But

in spite of giving all the best antibiotics and all supportive measures,

we kept losing these infants. When bird flu H1N1 cases were reported

from these South East Asia and India, we thought it might be a viral

cause and used Oseltamivir suspensions for such sick infants, but to no

avail. We contacted National Institute of Virolgy (NIV), Pune for

detailed virological analysis, but there was no response. Our diagnoses

for these infants varied from septicemia, viral encephalitis, right

heart failure (as echocardiographic findings showed pulmonary artery

hypertension, tricuspid regurgitation, and right heart dilatation) [1],

acute respiratory distress, shock etc as the final end stage

presentation. These deaths were an important component of the Infant

mortality rate (IMR) in Mizoram.

In December, 2014, having run

out of options, we started giving vitamin B-complex infusion (Vitneurin,

Beplex) along with the usual antibiotics and supportive care to these

infants. Following that practice, there was a dramatic change in the

outcome of these infants, and no more babies that came with these

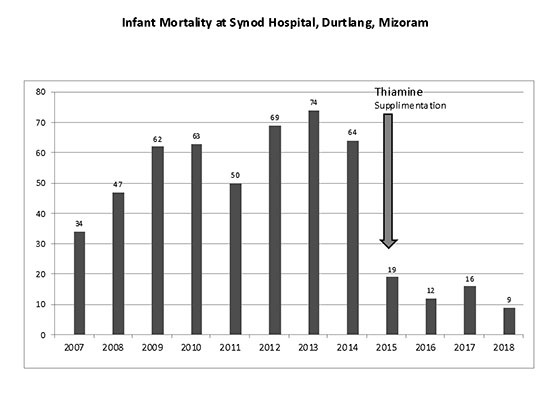

symptoms died in our hospital after that period (Fig. 1).

We concluded that we were dealing with infantile beriberi, and giving a

bolus of thiamine infusion and seeing the clinical response is the best

diagnostic method [2].

|

| Fig. 1 Infant

mortality at Synod Hospital, Durtlang before and after

routine thiamine supplementation in the post-partum

period. |

We presented our findings to the Department of Health

and Family Welfare of Mizoram (NHM) in Aizawl in March, 2015.

Convinced by our observations, a government order was issued for

all post-partum mothers to be given vitamin B complex tablets

from their time of delivery till their babies were six months of

age. These vitamin B complex tablets were to be dispensed from

the institution of delivery (District hospitals, PHCs, Sub

Centers) to last till their child’s first vaccination. Further,

vitamin B complex tablets were to be dispensed from sub- centers

on vaccination days.

The actions taken by the government

health authorities led to a marked decline in new cases of

infantile beriberi in the State of Mizoram. From 2015 onwards,

these cases just dried-up and the infant deaths dropped,

possibly also contributing to the lowering of infant mortality

rate of Mizoram.

Although, we did not find any

literature on universal B-complex supplementation for postpartum

mothers, it was better than waiting for infants to develop

beriberi.

We now know that thiamine deficiency is rampant

in Mizoram. These infants who died or came with the illness were

mostly low socio-economic families, the mothers were regular pan

chewers, and infants were on exclusive breast feeds. The risk of

beriberi is known to increase in individuals who consume a diet

high in thiaminase-rich foods (eg, raw freshwater fish or

shellfish, ferns), a diet high in anti-thiamine factors (eg,

tea, coffee, betel nuts), or both [3]. Since betel nuts cause

depletion in vitamin B1 stores and with a poor nutritional

intake, babies born to these mothers have a very poor chance of

survival. Breastfed infants whose mothers have thiamine

deficiency develop an infantile form of beriberi [4]. Providing

iron and calcium tablets to mothers does not help, if the mother

is thiamine-deficient [5].

Since supplementation for

pregnant women in India is only oral calcium, iron and folic

acid, it would be prudent to additionally provide vitamin B1, B6

and B12. This would go a long way in saving the lives of infant

born to thiamine-deficient mothers without additional

infrastructure and manpower inputs.

References

1. Jain SA, Kiran K, Krishna Kumar

R. Advances in pediatric cardiac emergencies. Indian J Pract

Pediatr. 2010;12:416.

2. Shivalkar B, Engelmann I, Carp

L. Shoshin syndrome: Two case reports representing opposite ends

of the same disease spectrum. Acta Cardiol. 1998; 53:195-9.

3. Vimokesant SL. Hilker DM, Nakornchai S, Rungruangsak

K, Dhanamitta S. Effect of betel nuts and fermented fish on the

thiamine status of Northeastern Thais. Am J Clin Nutr.

1975;28:1458-63.

4. Khounnorath S, Chamberlain K, Taylor

AM, Soukaloun D, Mayxay M, Lee SJ, et al. Clinically unapparent

infantile thiamine deficiency in Vientiane, Laos. PLoS Negl Trop

Dis. 2011;5:e969.

5. Mcgready R, Simpson JA, Cho T,

Dubowitz L, Changbumrung S, Böhm V, et al. Post-partum thiamine

deficiency in a Karen displaced population. Am J Clin Nutrition.

2001;74:808-13.

|

|

|

|

|