n medicine, a great deal of professional learning

occurs in the authentic work- environment, where residents learn on the

job, when they are exposed to real problems in daily practice [1]. One

of the outcomes of training during residency is to ensure that trainees

ultimately improve their patient-care practices. In order to achieve

this, residents must be able to evaluate their patient-care practices,

identify their strengths and deficiencies, and gather and critically

analyze scientific evidence. Having done this, they must be able to set

learning goals to offset their deficiencies and make feasible plans to

achieve them. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education

(ACGME) calls this competency Practice-based learning and improvement

(PBLI) [2,3]. The ACGME believes that assessment of these competencies

provide evidence of the effectiveness of the residency program and also

provide information to improve it further [4].Training in PBLI has also

been shown to lead to improved health outcomes in preventive care [5],

chronic disease management [6], and patient-safety [7].

The Medical Council of India (MCI) advocates that

postgraduate training should be competency-based and essentially

self-directed [8]. However, PBLI as a competency is not explicitly

stated in this document. There is also lack of expertise in teaching and

assessing PBLI in India. In teaching hospitals, the pressure of clinical

work often takes priority over resident-training. While residents are

expected to provide service, they must not be short-charged regarding

the quality of teaching. The prevailing scenario can be improved by

explicitly incorporating elements of PBLI in the residency training

curriculum.

Concept and Components

Practice based learning and improvement is best

described as a cyclical continuous process (Fig. 1) [9].

In an attempt to link education to quality of patient care, the ACGME

Outcome Project [10] defined eight constituent components under the core

competency of PBLI, which are summarized in Box 1.

|

|

Fig.1 Cycle of practice-based learning

and improvement.

|

|

Box 1

ACGME Components of Practice-based Learning and Improvement

|

|

In order to acquire the core competency of practice-based

learning and improvement, the learner should be able to:

1. Identify strengths, deficiencies and

limits in one’s knowledge and expertise

2. Set learning and improvement goals

3. Identify and perform appropriate learning

activities for personal and professional development

4. Incorporate formative evaluation feedback

into daily practice

5. Systematically analyze practice and

implement changes to improve practice

6. Locate, appraise, and assimilate evidence

from scientific studies

7. Use technology to optimize learning and

health care delivery

8. Participate in the education of patients, families, fellow

students and other health care professionals.

Source: Swing SR. The ACGME outcome project:

retrospective and prospective. Med Teacher. 2007;29:648-54.

|

Defining Milestones

In a competency-based education and training system,

the unit of progression is ‘mastery’ of specific knowledge and skills

[11]. The ACGME has defined the levels of proficiency expected at each

learning level [12]. Milestones have been identified for each

competency, which describe the performance level of skills, knowledge or

behavior that a learner is expected to demonstrate at a certain level of

professional development [13]. Breaking down these competencies into

observable milestones is useful both to the learner and to the assessor

as they help in determining an individual learner’s trajectory from a

beginner to a proficient practitioner.

ACGME suggests writing five levels of milestones [14]

based on the Dreyfus model of skill development [15], as discussed in an

earlier paper [16]. Milestones have been defined specifically for

different clinical specialties [11]. For Pediatrics, milestones under

different components of PBLI have been defined in several ways [17-22].

Web Table I illustrates different milestones under each

competency and provides practical examples of these.

Each of these PBLI competencies are discussed in

detail below:

1. Identify strengths, deficiencies and limits in

one’s knowledge and expertise

Learners may be able to identify their deficiencies

and limits because they are either: Motivated by external threat of a

negative consequence; e.g. punishment, morbidity, bad grades; or

Motivated by external positive consequence; e.g. reward, good

scores in examination, praise from superior; or Intrinsically motivated

by reward: such as ease of work, comfort, satisfaction of learning; or

Intrinsically motivated to excel and acquire expertise.

Identification of gaps serves as a stimulus to

identify their strengths and limitations in performance, by working hard

to master skills against required standards. Kolb [23] suggests that

when learners perceive gaps in knowledge, skills and attitudes on

reflecting on their experiences, they tend to engage in active

experimentation like applying new strategies to learn further. Schon’s

model [24] talks of the importance of reflection either before

("reflection for action") or during ("reflection in action") or after a

particular action ("reflection on action"). This pushes learners to seek

new knowledge in ambiguous situations and incorporate new knowledge into

practice.

2. Set learning and improvement goals

Self-directed learning is a process in which

"individuals take initiative (with or without the help of others) to

diagnose their own learning needs, formulate goals, identify human and

material resources for learning, choose and implement appropriate

learning strategies and evaluate learning outcomes" [25]. This task

requires them to formulate both short-term and long-term learning and

improvement goals. Triggers to discovering new learning needs can be:

questions which arise during patient care, while reading, during

conversations with other peers or while attending formal academic

sessions. Self-directedness is influenced by factors such as motivation,

self-regulation and self-efficacy [26].

3. Identify and perform appropriate learning

activities for personal and professional development

Learners must be aware of their preferred learning

styles [23] and must have sufficient understanding of what they need to

learn (in terms of knowledge, skills, behavioral change). They also need

to know what instructional methods most effectively and efficiently

address their specific learning needs and where they can access these

resources. This may require considerable discussion, consultation and

trial-and-error before identification of strategies that work best for

them.

4. Incorporate formative evaluation feedback into

daily practice

Formative feedback intends to improve specific

aspects of a learner’s performance by offering insight into their

behavior, rather than offering a judgment on overall performance [27].

Learners must eventually learn not only to listen to feedback and

incorporate it into their practice, but also be proactive in seeking

feedback for improvement. In practice, a learner must be aware of his

limitations and must know when a situation requires him to summon help

from a superior without compromising the safety of a patient.

5. Systematically analyze practice using quality

improvement methods and implement changes

Residents are expected to be able to apply their

knowledge of desired standards of patient care, standard protocols,

evidence-based guidelines and principles of quality improvement in their

day-to-day practice. They need to imbibe reflective practice and learn

how to manage change. If individuals are not trained in reflective

practice, they may turn defensive, when shown evidence for their need to

improve. In early stages, their focus might be on individual patients.

However, in the long run, clinicians will need to shift their focus to

their teams and to the system [28]. This can be taught by integrating

residents in the team which is involved in the hospital’s quality

improvement programs [29]. For example, an effort to improve the care of

low birth weight babies should also include attention to the system –

like the process of recording weight, record keeping, training of nurses

and other care providers, provision of nutritional advice and

availability of educational material.

6. Locate, appraise, and assimilate evidence from

scientific studies related to health problems of patients

The amount of medical information is ever-increasing

and clinicians must learn strategies to search for the evidence and

apply it in their practice [30]. Confronted with uncertainty in a

clinical case, the learner must be able to actively question the

rationale of patient care. For example, ‘In this patient, what is the

best antibiotic we should be using? What is the evidence we have for

this decision?’

One cannot practice evidence-based medicine (EBM)

without being able to set improvement goals for oneself or without being

motivated to be a lifelong learner. The skills required to be learnt in

order to practice have been detailed previously [17].

The milestones which characterize learners in various

stages of development of this sub-competency are illustrated through

examples in Web Table I. Learning EBM needs a steep

learning curve and a methodical approach. Several authors suggest

introducing EBM to undergraduates when time constraints are less. These

skills can subsequently be strengthened through actual practice during

residency training.

7. Use information technology to optimize

learning and healthcare delivery

Information technology is now vital to the practice

of medicine. The availability of the internet, the adoption of hospital

information systems and electronic health records (EHR) and use of

technology such as tablets and smartphones to provide access to

information at the point of care have changed the way in which clinical

medicine is practiced [31]. Medical colleges also have invested majorly

in computers and internet access.

Acceptance of technology is affected by perceived

ease of use and perceived usefulness. Of these, the perceived ease of

use has a greater impact on behavior and early learners must overcome

this hurdle to adopt technology [32,33]. While training new learners it

is important to keep in mind the following factors which determine early

perceptions of ease of use of a new system [34]:

• Internal control: Characterized by one’s

own sense of savviness with technology.

• External control: Perception of support

from facilitators with use of the new technology.

• Intrinsic motivation: Characterized by

‘computer playfulness’ or intrinsic enjoyment in interacting with

the technology.

• Emotion: Computer anxiety or negative

reaction to use of computers.

8. Participate in the education of patients,

families, fellow students and other healthcare professionals

Patient-education requires several skills and

capabilities such as: knowledge about the disease process, counseling

skills, and interpersonal and communication skills. Learners must be

trained in carrying out interactive, two-way, patient-centered

counseling sessions, while paying special attention to the behavioral,

psychosocial and environmental attributes of health and disease [35,36].

They must be able to perform data gathering, educate the patient,

negotiate and resolve issues, and demonstrate empathy [37].

Strategies to Impart Training in PBLI

Teaching the competency of PBLI may require different

pedagogical strategies compared to those used to foster

clinical-reasoning skills or patient-interaction skills. The basic

principles of designing these strategies are to clearly define key

learning outcomes, identify potential workplace settings which can be

opportunistically used to impart PBLI competencies and select engaging

and learning-rich experiences. The developmental milestones enumerated

in Web Table I will be useful to identify the level of the

learner and build on previous learning.

Learners must be encouraged to use both formal and

informal approaches. Some of these approaches are: use of study groups

with peers, problem solving exercises, formal clinical rotations, online

modules (for knowledge); demonstrations, simulations, review of video

recording of learner, deliberate practice (for skills); and sharing real

life experiences in discussions, behavioral interventions, and

appropriate role models (for behavior). Deliberate practice involves

improving and extending the reach and range of skills which one already

possesses. Deliberate practice entails consider-able, specific and

sustained efforts to develop expertise in something which the learner

cannot do well [38].

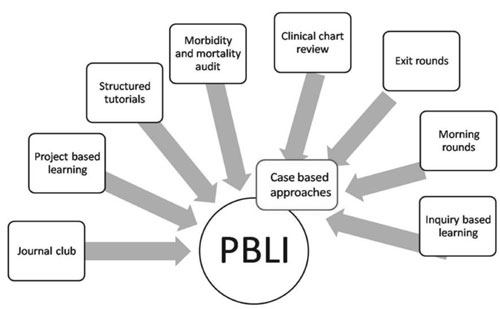

Literature has documented many teaching-learning

strategies ranging from small-group learning [39], workshops [40] to

project-based learning [41], which can help in fostering these behaviors

in learners. Many curricula and models have also been developed and

tested [42-44]. Some of the best documented instructional strategies for

cultivating PBLI behaviors in learners have been documented in the ACGME

project report [45] and are summarized in Fig.2. Some of

these instructional strategies are elaborated below:

|

|

Fig.2 Teaching-learning strategies to

cultivate practice-based learning and improvement behaviors in

learners.

|

Case-based approaches

A case, problem or inquiry is used to stimulate

discussion and impart learning. Based upon the level and nature of

inquiry, residents’ discussion can be observed, analyzed, evaluated and

critiqued as it reflects their level of knowledge, skills, and

attitudes. Probing can divulge the existing status of knowledge as well

as resident’s ability to recognize learning gaps. Some of the case based

approaches are:

• Inquiry-based learning: This model helps

learners develop the habit of inquiry by asking questions. These

questions may be posed to themselves or to other learners in the

group, thus fostering self-directed and autonomous learning.

Learners not only try to search for the right answers, but also

identify the gaps in their learning as far as knowledge and skills

are concerned and help to address them. This can be in the form of

reciprocal peer questioning. The model works on the presumption that

if critical thinkers are good questioners, the reverse is also true.

This helps in promoting skills of critical analysis and appraisal

[46].

• Morning rounds: Cases providing learning

opportunities can be chosen and patient-care can be reviewed during

rounds, with residents and students being asked to prepare possible

queries about the case. To widen the areas of learning opportunities

and improving the patient-care, case audits and case-census can also

be assimilated into the whole exercise [47].

• Exit rounds: Exit rounds tap the

opportunity of learning provided by recently discharged patients.

Residents reflect on the learning they have while working with these

patients. This provides with an opportunity to improve their patient

care practices too. Besides being a learning exercise, exit rounds

offer attending physicians an opportunity to evaluate students’

learning and performances [48].

• Clinical-chart review: A chart review

involves a systematic analysis of what has been done in the course

of clinical care of a patient, and how this could have been done

better. Patient chart review can help residents in identifying the

areas where they need improvement; gaps in their patient care

practice, and help them in taking critical action to improve their

patient outcomes. This exercise improves self-assessment and

critical analytical skills [43].

Morbidity and mortality audit

A morbidity and mortality audit is a specific audit

that tends to review negative clinical outcomes. A bizarre audit finding

can act as a lead and can direct further investigation into practice

patterns [49]. The resident scrutinizes an morbidity and mortality case

in terms of his or her own practice behaviors, reflects on it, and uses

that to improve practice behavior [43,50]. The resident presents a

description of the case, reflections on what went wrong, and a list of

resources used to gain a better understanding of the case. Presenters

are expected to challenge themselves with self-queries like what they

would do differently and what they would have to learn in order to

improve. Clinical teachers rate residents in areas of practice analysis,

improvement opportunity, resources to support analysis, and action plan

[50].

Structured-tutorials

A case under a resident’s care, which generated

uncertainty either during evaluation or management or counseling and

which definitely requires some action is chosen. The resident discusses

the case with a facilitator. Then a Medline search is conducted by the

resident for relevant literature review. Again a meeting with

facilitator is conducted and a tutorial is prepared. The same is

presented to the group in a structured-manner, giving questioning

opportunities after every session [51]. By utilizing their own clinical

cases, the residents appreciate the need to learn, identify

learning-gaps, and improve by self-reflection on real life situations,

thus improving PBLI skills.

Project-based learning

Residents work with a facilitator to recognize an

area of their practice that needs improvement, plan a

project-intervention to improve upon that gap, execute the improvement,

and establish its efficacy of the implementation during next year. By

learning their own practice-gaps and improving upon by self-reflection,

and implementation of improvement-project, the residents inculcate PBLI

skills [52].

Journal clubs

The focus of journal clubs can be one specific skill

(such as how to use likelihood ratios, or how a search strategy is

developed), and then specific articles can be chosen to teach that

particular skill. Residents must eventually learn how to weigh the

strength of the scientific evidence and regular sessions on critical

appraisal of journal articles are most valuable for this purpose.

While PBLI needs to be explicitly included in the

postgraduate training program, it can be introduced early in the

undergraduate curriculum with Early clinical exposure (ECE); using

student electives to reinforce the value of evidence-based medicine; and

by allowing undergraduates to shadow patients in the clinics.

Assessment of PBLI Competencies

Assessment of PBLI as a whole is difficult as it

spans different roles of a scholar, professional, manager, communicator,

and lifelong learner. It is not possible to measure all competencies

with a single assessment tool. Lack of validated and reliable tools to

assess this competency compounds the problem. Dependable methods of

assessment must be developed. By defining milestones for each

competency, assessment criteria specify the level of achievement or

mastery expected at each stage. During assessment, the rate of progress

of the learner’s knowledge, skills and behavior on each competency must

be documented.

Assessment of PBLI involves longitudinal observation

of the learner demonstrating self-directed learning behaviors, during

multiple encounters [17]. One option to demonstrate improvement is to

use the same assessment tool at different points along the training,

provided that the tool is able to consistently distinguish between the

different levels of performance.

It is important to clarify what will be assessed, how

and when the assessment will be conducted and who will be responsible

for assessment. Assessment can both be formative as well as summative.

Some of the approaches which have been used to assess PBLI are detailed

below:

Portfolios: Residents in most institutes in

India, use pre-formatted logbooks as a popular means to document

learning experiences in patient care. These are seldom taken seriously

and scarcely provide opportunities of reflective behavior, feedback and

improvement in patient care. Portfolios are a compilation of one’s

professional work and achievements over a period of time and can be used

to assess progress. Self-reflection is the inherent characteristic of

any portfolio-linked learning and professional development, and that’s

where they differ from logbooks, which are merely a compilation of

record of one’s work [53]. Reviewing and analyzing a portfolio along

with a mentor is a good strategy for a resident to receive formative

feedback [54]. Portfolios can also be maintained electronically to track

learner progress. The flexibility, comprehensiveness and potential for

integration offered by use of portfolios makes it a top choice for

assessment of PBLI competencies [9].

Medical record review and Chart-stimulated recall:

Patient records are reviewed during one-on-one sessions with faculty in

formal or informal settings using standardized forms. The focus of the

review can be resident’s decision making, medications given, tests

ordered, impact of interventions and their comparisons with standard

patient care guidelines.

Performance ratings using checklists or global rating

forms: Global assessment of competencies using rubrics or

observation checklists may be other methods of demonstrating progress of

learners [2,13]. Rubrics must clearly show how the learner has moved to

a higher level of performance on each competency. Checklists are useful

when competencies can be broken down into specific behaviors or actions.

Each clinical encounter requires enlisting of determined standards

before assessment can be implemented. Both checklists and rubrics

require trained raters to assess completeness and correctness of each

outcome.

Procedure or case logs: Residents prepare

summaries of patient care experiences or procedures, which include both

clinical data as well as their reflections [2]. These logs are useful

for documentation of experiences and deficiencies, and can form part of

the portfolio. Review of these logs with a faculty can be used to assess

PBLI competencies.

Evidence-based medicine skill test: Some

residency programs use written or oral EBM skill tests to assess

knowledge of critical appraisal. Different abilities–such as formulating

well-structured clinical questions; performing advanced literature

searches; and assessing validity of evidence in published studies can be

tested. The EBM skill test can be conducted several times; once before

exposure to EBM curriculum and after that to record improvement in

learning. Sustainability of improved behavior can be also assessed with

EBM skill tests [55].

Other methods: Multiple choice questions,

oral examination, use of standardized patients, objective structured

clinical examination, work-place based assessment [56] like

mini-clinical evaluation exercise (mini-CEX), 360° assessment and direct

observation of procedural skills (DOPS), can be used for formative and

summative assessment of PBLI. During 360° assessment or multisource

feedback, residents receive structured feedback using standard forms

from their peers, faculty, nurses, other staff and patients who observe

their work on a day-to-day basis during patient care. Feedback maybe

gathered on different aspects of their performance such as team work,

professionalism, communication skills, management skills or decision

making. These assessment forms could form part of the educational

portfolio. In all these methods, direct observation of the learner in

the workplace is followed by opportunities for reflection when

constructive feedback is given by the faculty.

Role of Faculty and Faculty Development

While we cannot emphasize the role of faculty in

nurturing these skills enough, it must be said that strong institutional

leadership and support are the keys to the effective implementation of

these competencies. A rigid regulatory framework, shortage of faculty,

unenthusiastic or overworked faculty, or lack of resources are all

possible impediments to the successful functioning of this programme.

Faculty is required to guide and nurture learners to

be self-directed [57]. Faculty or supervisors will be required to assist

learners in envisioning long-term broader goals and then breaking them

down into more achievable feasible short-term goals within a given time

frame. It is important for faculty in each department to diagnose the

stage of self-directedness that the learner lies in, so that they can

facilitate their movement from a less advanced to a more advanced stage

[58].

Faculty must be made aware of the importance of

ensuring that students are trained and assessed for the competencies

under PBLI. Faculty sensitization and training will be required to

identify opportunities within the existing curriculum to incorporate

PBLI training, provide constructive formative feedback, documentation of

progress of milestones achieved by students in a longitudinal manner and

assessment of competencies of PBLI. Ownership must be shared by several

collaborators.

The development of expertise requires faculty who

have the patience to observe students in their day-to-day work, and who

have the capability of delivering constructive, and sometimes difficult

feedback to the learner. Feedback which comes from a supervisor who has

directly observed the learner is always more acceptable. To provide

optimal feedback, faculty need to articulate it in a simple manner and

provide clear messages, facilitate reflection and guide learners on how

to translate learning goals into action [59]. Faculty must also have the

ability to mentor, support and challenge learners in a manner that they

are driven to achieve the next milestone. For skill acquisition, it is

useful here to remember that there will be variations in how learners

progress and acquire more advanced skills [15]. They must be given

enough guidance, feedback, experience and practice to be comfortable

with newer technologies.

Conclusion

Residents must be provided with ample opportunities

to experience and practice their skills, in order to move towards

acquiring expertise and acquire the competencies under practice based

learning and improvement. It is important that they develop

self-awareness of their abilities, are able to reflect on their

proficiency and find avenues to pursue lifelong learning. Training and

assessment of PBLI skills should be a mandatory part of the postgraduate

curriculum and strategies to foster PBLI skills should be interwoven

within all phases of training. Availability of milestones makes this

process feasible enough to implement in practice.

1. Spencer J. Learning and teaching in the clinical

environment. Br Med J. 2003;326:591-4.

2. Hayden SR, Dufel S, Shih R. Definitions and

competencies for practice-based learning and improvement. Acad Emerg

Med. 2002;9:1242-8.

3. Varkey P, Karlapudi S, Rose S, Nelson R, Warner M.

A systems approach for implementing practice-based learning and

improvement and systems-based practice in graduate medical education.

Acad Med.2009; 84: 335-9.

4. Swing SR. Assessing the ACGME general

competencies: General considerations and assessment methods. Acad Emerg

Med. 2002;9:1278-88.

5. Paukert JL, Chumley-Jones HS, Littlefield JH. Do

peer chart audits improve residents’ performance in providing preventive

care. Acad Med. 2003; 78 (suppl 10):S39-41.

6. Sutherland JE, Hoehns JD, O’Donnell B, Wiblin RT.

Diabetes management quality improvement in a family medicine residency

program. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2001;14:243-51.

7. Parenti CM, Lederle FA, Impola CL, Peterson LR.

Reduction of unnecessary intravenous catheter use: Internal medicine

house staffparticipate in a successful quality improvement project. Arch

Intern Med. 1994;154:1829-32.

8. Medical Council of India. Post Graduate Medical

Education Regulations 2000. Available from:

http://www.mciindia.org/RulesandRegulations/PGMedical

EducationRegulations2000.aspx. Accessed July 17, 2016.

9. Lynch DC, Swing SR, Horowitz SD, Holt K, Messer

JV. Assessing practice-based learning and improvement. Teach Learn Med.

2004; 16: 85-92.

10. Swing SR. The ACGME outcome project:

retrospective and prospective. Med Teacher. 2007;29:648-54.

11. Sullivan RL. The Competency-based Approach to

Training. Strategy Paper No 1. JHPIEGO Corporation: Baltimore, Maryland;

1995. Available from: http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pnacg569.pdf.

Accessed July 17, 2016.

12. Nasca T. The next step in the outcomes-based

accreditation project. ACGME Bull. 2008;2-4.

13. Swing SR, Beeson MS, Carraccio C, Coburn M, Lobst

W, Selden NR, et al. Educational milestone development in the

first 7 specialties to enter the next accreditation system. J Grad Med

Educ. 2013;5:98-106.

14. Holmboe ES, Edgar L, Hamstra S. ACGME: The

Milestones Guidebook; Version 2016. Available from:

https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/MilestonesGuidebook. pdf. Accessed

July 17, 2016.

15. Dreyfus HL, Dreyfus SE. Mind over Machine. New

York, NY: Free Press; 1988.

16. Dhaliwal U, Gupta P, Singh T. Entrustable

professional activities: Teaching and assessing clinical competence.

Indian Pediatr. 2015; 52: 591-7.

17. Burke AE, Benson B, Englander R, Carraccio C,

Hicks PJ. Domain of competence: Practice-based learning and improvement.

Acad Pediatr. 2014; 14: S38-S54.

18. Hicks PJ, Schumacher DJ, Benson BJ, Burke AE,

Englander R, Guralnick S, et al. The pediatrics milestones:

conceptual framework, guiding principles, and approach to development. J

Grad Med Educ. 2010; 2:410-8.

19. American Board of Pediatrics and Accreditation

Council for Graduate Medical Education. The Pediatrics Milestone

Project. Available from: https://www.abp. org/abpwebsite/publicat/milestones.pdf.

Accessed July 17, 2016.

20. Englander R, Burke A, Guralnick S, Benson B,

Hicks PJ, Ludwing S, et al. The pediatric milestones: a

continuous quality improvement project is launched-now the hard work

begins! Acad Pediatr. 2012;12:471-4.

21. Hicks PJ, Englander R, Schumacher DJ, Burke A,

Benson BJ, Gurulnick S, et al. Pediatrics milestone project: next

steps toward meaningful outcomes assessment. J Grad Med Educ.

2010;2:577-84.

22. Schumacher DJ, Lewis KO, Burke AE, Smith ML,

Schumacher JB, Pitman MA, et al. The pediatrics milestones:

initial evidence for their use as learning roadmaps for residents. Acad

Pediatr. 2013;13:40-7.

23. Kolb D. Experiential Learning as the Science of

Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1984.

24. Schon D. Educating the Reűective Practitioner.

San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1987.

25. Knowles MS. Self-Directed Learning. A Guide for

Learners and Teachers. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall/Cambridge; 1975.

26. Morris C, Blaney D. Work-Based Learning. In:

Swanwick T, (editor). Understanding Medical Education: Evidence, Theory

and Practice. Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK; 2010.

27. Ende J. Feedback in clinical medical education.

JAMA. 1983;250:777-81.

28. Moore LG, Wasson JH. Improving efficiency,

quality and the doctor–patient relationship. Fam Pract Manag.

2007;14:20-4.

29. Ashton CM. "Invisible doctors": making a case for

involving medical residents in hospital quality improvement programs.

Acad Med. 1993;68:823-4.

30. Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB,

Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t.

BMJ. 1996;312:71-2.

31. Duncan J, Evens R. Using information to optimize

medical outcomes. JAMA. 2009;301:2383-5.

32. Davis FD. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of

use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q.

1989;13:319-39.

33. Davis FD, Bagozzi RP, Warshaw PR. User acceptance

of computer technology: a comparison of two theoretical models. Manage

Sci. 1989;35:982-1002.

34. Venkatesh V. Determinants of perceived ease of

use: integrating control,intrinsic motivation, and emotion into the

technology acceptance model. Inf Syst Res. 2000;11:342-65.

35. Bird J, Cohen-Cole SA. The three function model

of the medical interview. An educational device. Adv Psychosom Med.

1990;20:65-88.

36. Lazare A, Putnam SM, Lipkin M. Jr. Three

functions of the medical interview. In: Lipkin M Jr., Putnam SM,

Lazare A, editors. The Medical Interview: Clinical Care, Education, and

Research. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 1995. pp. 3-19.

37. Modi JN, Anshu, Chhatwal J, Gupta P, Singh T.

Teaching and assessing communication skills in medical undergraduate

training. Indian Pediatr. 2016;53: 497-504.

38. Ericsson KA, Prietula MJ, Cokely ET. The making

of an expert. Harv Bus Rev. 2007;85:114-21.

39. Canal DF, Torbeck L, Djuricich AM. Practice-based

learning and improvement: a curriculum in continuous quality improvement

for surgery residents. Arch Surg. 2007;142:479-83.

40. Morrison LJ, Headrick LA. Teaching residents

about practice-based learning and improvement. Jt Comm J Qual Patient

Saf. 2008;34:453-9.

41. Ogrinc G, Headrick LA, Morrison LJ, Foster T.

Teaching and assessing resident competence in practice-based learning

and improvement. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19 496-500.

42. Peters AS, Kimura J, Ladden JD, March E, Moore

GT. A self-instructional model to teach systems-based practice and

practice-based learning and improvement. J Gen Intern Med.

2008;23:931-6.

43. Ziegelstein RC, Fiebach NH. The mirror and the

village: A new method for teaching practice-based learning and

improvement and systems-based practice. Acad Med. 2004;79:83-8.

44. Tomolo AM, Lawrence RH, Watts B, Augustine S,

Aron DC, Singh MK. Pilot study evaluating a practice-based learning and

improvement curriculum focusing on the development of system-level

quality improvement skills. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3:49-58.

45. ACGME Outcome Project. Enhancing residency

education through outcomes assessment - Advancing education in

practice-based learning and improvement. Available from:

https://www.usahealthsystem.com/workfiles/com_docs/gme/2011%20Links/Practice%20Based%20Learning.

ACGME.pdf. Accessed July 17, 2016.

46. King A. Designing the instructional process to

enhance critical thinking across the curriculum. Teach Psychol.

1995;22:13-7.

47. Whelan CT, Podrazik PM, Johnson JK. A case based

approach to teaching practice-based learning and improvement on the

wards. Semin Med Pract. 2005; 8: 64-74.

48. Arseneau R. Exit rounds: A reflection exercise.

Acad Med. 1995;70: 684-7.

49. Yaffe MJ, Gupta G, Still S, Boillat M, Russillio

B, Schiff B, et al. Morbidity and mortality audits. Can Fam

Physician. 2005;51:234-9.

50. Rosenfeld JC. Using the morbidity and mortality

conference to teach and assess the ACGME general competencies. Curr

Surg. 2005;62:664-9.

51. Green ML, Ellis PJ. Impact of an evidence-based

medicine curriculum based on adult learning theory. J Gen Intern Med.

1997;12:742-50.

52. Lough JRM, Murray TS. Audit and summative

assessment: a completed audit cycle. Med Educ. 2001;35:357-63.

53. Joshi M, Gupta P, Singh T. Portfolio-based

learning and assessment. Indian Pediatr. 2015;52:231-5.

54. Salzman DH, Franzen DS, Leone KA, Kessler CS.

Assessing practice-based learning and improvement. Acad Emerg Med.

2012;19:1403-10.

55. Smith CA, Ganschow PS, Reilly BM. Teaching

residents evidence-based medicine skills: a controlled trial of

effectiveness and assessment of durability. J Gen Intern Med.

2000;15:710-5.

56. Singh T, Modi JN. Workplace-based assessment: A

step to promote competency based postgraduate training. Indian Pediatr.

2013;50:553-9.

57. Schmidt H. Assumptions underlying self-directed

learning may be false. Med Educ. 2000;34:243-5.

58. Grow GO. Teaching learners to be self-directed.

Adult Educ Q. 1991;41:125-49.

59. Nichol DJ, Macfarlane-Dick D. Formative

assessment and self-regulated learning: a model and seven principles for

good feedback practice. Stud Higher Educ. 2006;31: 199-218.