|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2014;51:

312-314 |

|

Tuberous Sclerosis Presenting with Hemorrhagic

Stroke

|

|

Radheshyam Purkait, Sreyasi Bhattacharya,

Birendranath Roy and *Ramchandra Bhadra

From Departments of Pediatric Medicine and

*Radiology, NRS Medical College and Hospital, Kolkata-700014. WB, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Radheshyam Purkait,

Email:

[email protected]

Received: December 19, 2013;

Initial review: February 04, 2014;

Accepted: March 06, 2014.

|

|

Background: Incidence of intracerebral hemorrhage in patients with

tuberous sclerosis is rare, and in most of the cases it is associated

with either underlying cerebrovascular malformation or hemorrhage into

the subependymal giant cell astrocytoma. Case characteristics: A

2-year-old boy presented with a hemorrhagic stroke, and subsequently

diagnosed as a case of tuberous sclerosis. Observation: Detailed

work-up for stroke did not reveal any definite etiology. Outcome:

Weakness gradually improved. Follow-up neuroimaging showed resolution of

hemorrhage. Message: Clinician must be aware regarding this rare

presentation of tuberous sclerosis.

Keywords: Cerebral hemorrhage, Child, Stroke.

|

|

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is an autosomal

dominant neurocutaneous syndrome with variable penetrance; the estimated

frequency is approximately one in 6,000 newborns [1,2]. Although a wide

variety of central nervous system abnormalities are associated with TSC,

intracerebral hemorrhage is rare [3-9].

Case Report

A 2-year-old boy presented with history of sudden

onset repeated vomiting, loss of consciousness, recurrent attacks of

generalized tonic-clonic seizures, and left-sided hemiparesis. There was

no history of trauma or antecedent surgery, congenital cyanotic heart

disease, dehydration, tuberculosis or bleeding disorders. Child was

previously admitted to a local hospital where he was treated with

phenytoin and aspirin. Past history revealed that he was suffering from

recurrent focal seizures since six months of age for which he was

prescribed sodium valproate, but the drug compliance was poor for the

last three months. He was born out of a non-consanguineous marriage and

had two siblings. His elder brother was also suffering from similar kind

of focal seizures since early infancy, and had profound mental

disability.

At presentation, he was afebrile but comatose with

Glasgow Coma Scale of E2V2M3 with stable vital signs, including blood

pressure. On examination, he had spasticity and weakness in the left

upper and lower limb, positive Babinski sign and exaggerated deep tendon

reflexes on the left side. Ophthalmological examination showed

mid-dilated pupils with sluggish reaction to light and bilateral

papilledema. Child had no signs of meningeal irritation or any cranial

nerve involvement. Multiple hypopigmented macules were noted over the

face, abdomen and trunk of the child. Other systemic examination was

unremarkable.

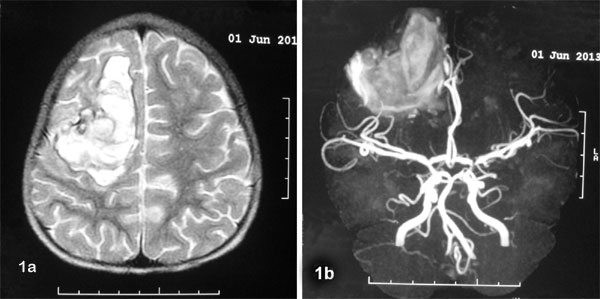

Routine hematological and biochemical investi-gations

were normal. A non-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of brain

showed massive acute intracranial hemorrhage with perilesional edema

located in the right fronto-parietal region with multiple

periventricular subependymal calcified nodules (Fig. 1a).

MR angiography did not detect any vascular abnormality except

intracerebral hemorrhage (Fig. 1b).

|

|

Fig. 1 (a) Non-enhanced CT scan

showing large intracranial hemorrhage with perilesional edema

located in the right fronto-parietal region as well as multiple

periventricular subependymal calcified nodules; (b) MR

angiography showing intracranial hemorrhage in the right fronto-parietal

region without any abnormality in the major cerebral vessels.

|

Protein C and protein S level, blood lactate levels,

Carotid doppler study, and abdominal ultrasound were non-contributory.

Ophthalmological examination did not reveal any retinal abnormality. 2D

Echocardiography showed two masses, one in left ventricle of size 16×14

mm, attached to the intraventricular septum, and another (10×10 mm) in

the right ventricle suggestive of rhabdomyoma. In view of history,

clinical examination and investigations, including neuroimaging, the

child was diagnosed as a case of tuberous sclerosis. Other family

members were assessed; except mother, all had TSC but the clinical

presentations were varied. Child improved gradually on medical

management and discharged with the advice to continue sodium valproate

and physiotherapy. CT scan repeated at 3 month of follow-up visit showed

resolution of hemorrhage.

Discussion

Tuber is the characteristic brain lesion of TSC, and

may rarely differentiate into a malignant subependymal giant cell

astrocytoma. The most common neurologic manifestations are seizures,

cognitive impairment, and behavioral abnormalities, including autism

[1].

In TSC, intracerebral hemorrhage – with or without

intraventricular component – is rare. In most of the reported cases, it

was associated with either underlying cerebrovascular malformation, like

ectasia, aneurysm and arteriovenous malformation or hemorrhage into the

subependymal giant cell astrocytoma [3-9]. The underlying

pathophysiologic mechanism of intratumoral hemorrhage remains unclear;

increased venous pressure secondary to an increased intracranial

pressure is the most accepted pathogenesis leading to necrosis and

hemorrhage [6].

In the present case, neither vascular anomaly nor

intratumor hemorrhage was detected. Other possible etiologies like

hypertension, primary or metastatic central nervous system malignancy,

leukemia, coagulopathy, use of drugs like warfarin, amphetamines,

cocaine, phenypropanolamine, history of head trauma or antecedent

intracranial surgery were excluded. Although the etiology remains

unexplained in the index case, possibility of early hemorrhagic

transformation of an underlying embolic ischemic infarction could not be

ruled out as the probable pathophysiologic mechanism where cardiac

tumours were the potential source of emboli [10].

Contributors: RP: diagnosed, worked up the case

and wrote the manuscript; SB and BR: managed the case and reviewed the

literature; RP and RB: prepared the final manuscript and followed up the

case.

Funding: None; Competing interests: None

stated.

References

1. Sahin M. Tuberous Sclerosis. In: Kliegman

RM, Stanton BF, St. Geme JW, Schor NF, Behrman RE, editors. Nelson

Textbook of Pediatrics. 19th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2012.

p.2049-51.

2. Irvine AD, Mellerio JE. Genetics and

Genodermatoses: Tuberous sclerosis complex. In: Burns T,

Breathnach, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology.

8th ed. UK: Willey-Blackwell; 2010. p.15.21-25.

3. Spangler WJ, Cosgrove GR, Moumdjian RA, Montes JL.

Cerebral arterial ectasia and tuberous sclerosis: case report.

Neurosurgery. 1997;40:191-3.

4. Sabat SB, Cure J, Sullivan J, Gujrathi R. Tuberous

sclerosis with multiple intracranial aneurysms: atypical tuberous

sclerosis diagnosed in adult due to third nerve palsy. Acta Neurol Belg.

2010;110:89-92.

5. Guridi J, Tuñón M, Caballero C, Gallo-Ruiz A,

Vázquez A, Zazpe I. Intracranial hemorrhage from an arteriovenous

malformation (AVM) in a tuberous sclerosis patient. Neurologia.

2001;16:281-4.

6. Waga S, Yamamoto Y, Kojima T, Sakakura M. Massive

hemorrhage in tumor of tuberous sclerosis. Surg Neurol. 1977;8:99-101.

7. Barbosa-Coutinho LM, Lima EL, Gadret RO, Ferreira

NP. Massive intratumor hemorrhage in tuberous sclerosis. Autopsy study

of a case. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 1991;49:465-70.

8. Kalina P, Drehobl KE, Greenberg RW, Black KS,

Hyman RA. Hemorrhagic subependymal giant cell astrocytoma. Pediatr

Radiol. 1995;25:66-7.

9. Wadhwa R, Khan IS, Thomas JO, Nanda A, Guthikonda

B. Hemorrhagic subependymal giant cell astrocytoma in a patient with

tuberous sclerosis: case report and review of the literature. Neurol

India. 2011;59:933-5.

10. Hoque R, Gonzalez-Toledo E, Minagar A, Kelley RE.

Circuitous embolic hemorrhagic stroke: carotid pseudoaneurysm to fetal

posterior cerebral artery conduit: a case report. J Med Case Rep.

2008;2:61.

|

|

|

|

|