|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2010;47: 317-322 |

|

Aerosolized L-epinephrine vs Budesonide

for Post-extubation Stridor: A Randomized Controlled Trial |

|

A Sinha, M Jayashree and S Singhi

From the Department of Pediatrics, Postgraduate Institute

of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Jayashree Muralidharan, Additional

Professor of Pediatrics, Advanced Pediatrics Centre, PGIMER, Chandigarh

160 012, India. Email:

[email protected]

Received: August 8, 2008;

Initial review: August 29, 2008;

Accepted: April 24, 2009.

Published

online: 2009 September 3.

PII:S097475590800491-1

|

|

Abstract

Objective: To compare the efficacy and adverse

effects of aerosolized L-epinephrine vs budesonide in the

treatment of post-extubation stridor.

Study design: Randomized controlled trial.

Setting: Pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) of

a tertiary teaching and referral hospital.

Subjects: Sixty two patients with a stridor score

³4 following extubation.

Intervention: Patients were randomized to receive

either aerosolized L-epinephrine (n=32) or budesonide (n

=30). Respiratory rate, heart rate, stridor score, blood pressure and

oxygen saturation were recorded from 0 min to 24 hours.

Outcome measures: Stridor score remaining at

³4, need for re-nebulization and re-intubation

between 20 min –24 hours were primary outcome measures. Tachycardia (HR

> normal for age), hypertension (BP >95th centile for age) and hypoxia

(SpO2 <92% for 5 min) were secondary outcome measures.

Results: Both drugs showed a significant and

comparable decline in the median (95% CI) stridor scores from baseline

to 60 min [4 (4.10-4.50) to 2.00 (1.46-2.67) for budesonide vs 4

(4.12-5.00) to 2.00 (1.31 -2.75) for epinephrine]. At 2 hours, the

stridor scores were significantly lower in the epinephrine as compared

to budesonide group [0.00 (0.69-1.81) vs 3.00(1.75-3.32); P

=0.02)]. However, the proportion of patients with stridor score

³4 at any time between 20min-24 hrs

(53.3% vs 53.1%; P=0.99), need for renebulization (40 %

vs 43.8 %; P=0.76) and re-intubation (20% vs 25%, P=0.638),

and adverse effects were similar in both groups.

Conclusions: Both aerosolized L-epinephrine and

budesonide were equally effective in their initial therapeutic response

in post-extubation stridor. However, epinephrine showed a more sustained

effect.

Key words: Budesonide, Epinephrine, Extubation, Stridor.

|

|

T

he most serious and immediate

complication of extubation in young

children is laryngeal edema; the incidence

of post extubation stridor in the Pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) is

described to be between 2-25%(1-5). Aerosolized epinephrine has been found

to be an effective therapy in both infective and postextubation

stridor(6,7). The action of epinephrine, however, is transient and there

is a potential risk of rebound laryngeal edema, which may limit the

repeated use of this drug(7). Treatment with steroids provides a sustained

effect due to their anti-inflammatory action. Intravenous dexamethasone

was found to be effective in pre-extubation and post- extubation states

thus decreasing the risk of

post-extubation stridor by around 40%(8). Theoretically, inhaled steroids

with a similar mechanism of action as systemic steroids should be more

advantageous due to direct delivery at the site of action, lesser dose

needed and fewer side effects. Thus, aerosolized budesonide when used in

the treatment of croup was found to reduce edema without any side

effects(9,10). Trials comparing aerosolized epinephrine and budesonide in

the treatment of infective croup have shown similar efficacy and safety of

both the drugs(11). However, there are no studies comparing these two

drugs in the treatment of post-extubation stridor.

Methods

The trial was conducted in the PICU of a

multispeciality urban teaching and referral hospital with 1200 beds over a

period of 11 months from February 2004 to January 2005, after approval

from the Institute’s Ethics Committee.

Patients demonstrating hoarseness of voice, barking

cough and/or inspiratory stridor with a stridor score

³4 (Table I)

after extubation, were enrolled after obtaining a written informed consent

from parents or guardians. The demographic details, admission diagnosis,

indication for PICU admission, Pediatric risk of mortality (PRISM) III

scores, duration of mechanical ventilation and indication, type and

duration of intubation were recorded at the time of inclusion.

TABLE I

Stridor Scoring System

|

Clinical findings |

Points |

|

Level of consciousness |

|

Normal (including sleep) |

0 |

|

Altered mental status (lethargy) |

5 |

|

Cyanosis in room air |

|

None |

0 |

|

When agitated |

4 |

|

Cyanosis at rest |

5 |

|

Inspiratory stridor |

|

None |

0 |

|

When agitated |

1 |

|

At rest |

2 |

|

Air movement |

|

Normal |

0 |

|

Decreased |

1 |

|

Markedly decreased |

2 |

|

Retractions |

|

None |

0 |

|

Mild (alar flaring) |

1 |

|

Moderate (suprasternal and intercostal) |

2 |

|

Severe (all accessory muscles used) |

3 |

|

Maximum total points |

17 |

|

Adapted from Nutman, et al.(6). |

Following extubation, all patients were administered

humidified oxygen by nasal prongs or facemask with an oxygen flow of

6L/min. Patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were randomized to

receive either aerosolized L-epinephrine [(Group I (E)] or budesonide

[Group II (B)]. Randomization by stratification (varying block

randomization) was done so as to distribute patients with primary upper

airway disease into both groups evenly. A primary upper airway disease was

defined as primary pharyngeal, laryngeal or tracheal infections, trauma to

upper airway or anatomical malformations of upper airway. A person who was

not directly involved in the study did the random number allocation.

After randomization, Group I(E) received L- epinephrine

1% solution 0.25mL in 2mL normal saline, nebulized over 15-20 min with

face mask and 6L/min of oxygen flow. Group II (B) received budesonide

1000µg (2mL) nebulized over 15-20 min with face mask and 6L/min of O 2

flow. Respiratory rate (RR), stridor score, heart rate (HR), blood

pressure (BP) and oxygen saturation (SpO2)

were recorded for each patient immediately before aerosol administration

(time 0) and at 20, 40 and 60 mins; and at 2, 4, 8, 12 and 24 hours.

Stridor score remaining at

³4,

need for re-nebulisation, and/or re-intubation at any time between 20

min-24 h were identified as primary outcome variables.

Children in whom the stridor score remained

³4 or worsened after

receiving therapy, were re-nebulized with L-epinephrine (conventional

protocol). The need for reintubation was decided by the treating physician

based on combination of variables i.e. HR, RR, stridor score and

SpO2.

Sample size: Assuming a failure rate of 40%

in L-epinephrine group and a desired reduction of failure rate to 10% in

the budesonide group, with an

a

error of 5% and power of 80%, we calculated that approximately 30 subjects

would be required in each group.

Statistical analysis: Data are presented as

mean±SD, median and percentages wherever applicable. Parametric data were

analyzed using the Student’s‘t’ test and non-parametric data with

Mann- Whitney U test. Categorical data were analyzed with Chi-sqaure or

Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables measured at different time

intervals between the groups were compared using the repeated measures

ANOVA. The linear trend in proportion between the groups was analyzed with

Chi-square. The statistical packages used in the study were SPSS (version

10.0) and Epi Info 2000 (version 6.0).

Results

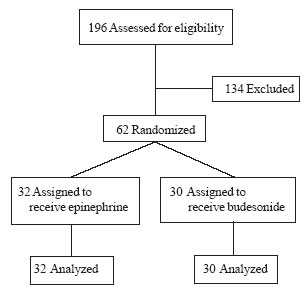

Of the 370 patients admitted to the PICU during the

study period, 196 (52.9%) were intubated for various reasons. Sixty-two

(31.6%) of the intubated patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria and

were randomized (Fig.1). Their baseline characteristics are

summarized in Table II.

|

|

Fig. 1 Study flow chart.

|

TABLE II

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Subjects

|

|

Group I (E) n=32 |

Group II (B) n=30 |

P value |

|

Age (mo), mean ± SD |

34.7 ± 38.4 |

38.6±41.9 |

0.80* |

|

Males |

26 |

24 |

0.58*** |

|

PRISM score, median (Centile range) |

17 (5-36) |

15 (3-33) |

0.72** |

|

Indication for intubation n (%) |

|

Respiratory failure |

11(34.4) |

11(36.7) |

|

|

Shock |

6 (18.8) |

2 (6.7) |

|

|

Respiratory failure + shock |

3 (9.4) |

3 (10) |

0.57*** |

|

Low Glasgow Coma score |

4 (12.5) |

3 (10) |

|

|

Raised Intracranial pressure |

4 (12.5) |

9 (30) |

|

|

Upper airway obstruction |

4 (12.5) |

2 (6.7) |

|

|

Duration(d), median (range) |

|

Intubation |

10 (3-33) |

8.5 (2-50) |

0.55** |

|

Mechanical Ventilation |

9 (1-32) |

7.5 (2-39) |

0.79** |

|

Stridor score, median# |

4 (4-5.5) |

4 (4-5) |

0.59** |

|

Respiratory rate, mean ± SD |

35.9 ± 6.6 |

38.3 ± 8 |

0.19* |

|

Heart rate, mean ± SD |

119.8 ± 20.4 |

132.8 ± 19.3 |

0.01* |

|

Systolic blood pressure, mean ± SD |

98 ± 10.2 |

100.5 ± 16.2 |

0.47* |

|

Diastolic blood pressure, mean ± SD |

59.6 ± 12.2 |

64.5 ± 15.7 |

0.17* |

|

O2 saturation, mean ± S.D |

95.9±15.8 |

98.7 ± 2 |

0.25* |

*Student’s ‘t’ test, **Mann Whitney U test, ***Chi Square test.

|

The median (95% CI) stridor scores from baseline (0min)

to 24 hours and corresponding proportion of subjects with stridor score

³4 at different

time intervals is depicted in Table III. The proportion of

patients with stridor score

³4

at any time between 20min-24 hrs between budesonide and epinephrine group

was 53.3% and 53.1%, respectively (P=0.99).

TABLE III

Stridor Score ≥4 at Different Time Intervals

|

Time Interval |

Group |

Group |

P |

| |

II(B) |

I (E) |

value |

|

Baseline |

|

Stridor score ≥4; n (%) |

– |

– |

– |

|

Median score (5-95th centile) |

4 (4-5) |

4 (4-8) |

0.59 |

|

20 min |

|

Stridor score ≥4; n (%) |

11(36.7%) |

9 (28.1%) |

0.47 |

|

Median (5-95th centile) |

2.5 (1-5) |

2.5 (0-5) |

0.79 |

|

40min |

|

Stridor Score ≥4; n (%) |

8 (26.7%) |

8 (25.0%) |

0.88 |

|

Median (5-95th centile) |

2 (0-4) |

2 (0-5) |

0.91 |

|

60min |

|

Stridor score ≥4; n (%) |

6 (20%) |

6 (18.8%) |

0.90 |

|

Median (5-95th centile) |

2 (0-5) |

2 (0-6) |

0.68 |

|

2 hours |

|

Stridor score ≥4; n (%) |

10 (33.3%) |

5 (15.6%) |

0.10 |

|

Median (5-95th centile) |

3 (0-5) |

0 (0-4) |

0.01* |

|

4 hours |

|

Stridor score ≥4; n (%) |

5 (16.7%) |

5 (15.6%) |

0.91 |

|

Median (5-95th centile) |

1.00 (0-4) |

0.00 (0-4) |

0.45 |

|

8 hours |

|

Stridor score ≥4; n (%) |

4 (13.3%) |

4 (12.5%) |

0.92 |

|

Median (5-95th centile) |

1 (0-4) |

0 (0-4) |

0.09 |

|

12 hours |

|

Stridor score ≥4; n (%) |

2 (6.7%) |

4 (12.5%) |

0.44 |

|

Median (5-95th centile) |

0 (0-4) |

0 (0-4) |

0.67 |

|

24 hours |

|

Stridor score ≥4; n (%) |

0 |

1(3.1%) |

0.33 |

|

Median (5-95th centile) |

0 (0-3) |

0 (0-3) |

0.35 |

|

*P value < 0.05 by Mann Whitney U test. |

Twelve patients (40%) in the epinephrine group and 14

patients (43.8%) in the budesonide group required re-nebulization (P=

0.76). The median time taken from initiation of study treatment to need

for subsequent re-nebulization was significantly longer in epinephrine

group as compared to budesonide group [(120 (60-720) min vs 90

(60-240 min)], (P=0.04). Re-nebulized patients who developed

hypoxia or showed signs of increased work of breathing were re-intubated.

The proportion of patients needing re-intubation was similar in both the

groups [epinephrine: 8 (25%) and budesonide: 6 (20%); P= 0.64]. The

median time to re-intubation was also similar [budesonide: 120 (120-720)

min and epinephrine: 150 (60-720) min].

The trends in RR, HR, systolic and diastolic BP and SpO 2 in both groups were not significantly different when

assessed over time. Frequency of sinus tachycardia within 2 hours of

aerosolized therapy was similar in both the groups [10 (31.3%) in

epinephrine vs 7 (23.3%) in budesonide group]. Transient

hypertension was noted in 4 patients (12.5%) in epinephrine as compared to

2 (6.7%) in budesonide group.

Discussion

The incidence of post-extubation stridor in our

patients was 31.6%, similar to that reported previously(12,13). Both

aerosolized epinephrine and budesonide were similar with respect to their

rapid therapeutic action. Epinephrine, however, showed a statistically

significant sustained effect at 2 hours post-nebulization. The proportion

of patients with stridor score

³4,

need for re-intubation and re-nebulization were similar in both the

groups. The frequency of adverse effects in both the groups were also

similar.

The rapid onset of action of aerosolized epinephrine

and budesonide postulated due to local vasoconstrictor effect mediated by

a-adrenergic

receptors has been observed by several authors(6,7, 9,11,15). Our findings

in the epinephrine group are in concordance with observations of Westley,

et al.(7) and Waisman, et al.(15) who had shown a

similar change in croup score at 30 min post nebulization lasting for

60-90 min. Rapid response with budesonide observed by us was also similar

to the findings of Husby, et al.(9) and Fitzgerald, et al.(11),

who reported a significant change in the mean croup scores from baseline

to 30 min post-nebulization(9, 11). The trend of response observed by us

at 2 hours post nebulization was different in that epinephrine showed a

significant and sustained improvement as compared to budesonide. Majority

of the published reviews have, however, reported a trend to the contrary –

supporting the contention that the response to nebulized epinephrine is

rapid and transitory and that to budesonide more sustained(7, 10,16).

Klassen, et al.(16) and Godden, et al.(10) found a

significant reduction in croup scores at 4 hours and 2 hours with aerosolized budesonide in the treatment of

children with croup, thus reiterating the sustained nature of the drug

effect. The sustained effect of steroids is attributed to their

anti-inflammatory effects, which are usually not apparent until 6 hours

after treatment(9). The statistically significant difference in the

therapeutic response between epinephrine and budesonide observed by us at

2 hours was possibly not clinically meaningful as the proportion of

patients with a stridor score of

³4

in both groups was similar at that point. Additionally, the subsequent

rate of re-nebulization and re-intubation was also similar in both the

groups. Since there were more patients with raised intracranial pressure

in the latter, it is possible that the poor outcomes in the form of

worsening stridor scores were related to the effects of raised ICP causing

aggravation of airway problems and not to the direct drug effect per se.

The incidence of re-nebulization, though similar in

both the groups, was higher than that reported previously(11). The lower

incidence observed by Fitzgerald, et al.(11) was possibly

related to the additional effect of systemic steroids that were given in

14 (40%) and 15 (48.4%) patients in the budesonide and epinephrine group,

respectively. The reasons for the relatively higher incidence in our

patients remains unclear. Nearly one-third of patients in both groups had

sinus tachycardia within 2 hours of aerosolized therapy unlike the

previously reported trend(6,15,17). Tachycardia in the budesonide group

was probably secondary to worsening stridor scores and increased work of

breathing rather than to direct drug effect as seen in the epinephrine

group. Transient systolic hyper-tension was noted in minority of patients

in both the groups. Though the dose used in our study was similar to

others, most of the studies have reported lack of significant change in

blood pressure with both the drugs(6,7,9,10).

The major limitation of our study is inclusion of

patients with upper airway disease. Though evenly distributed, these are

different pathologies bearing different post extubation criteria and

course. Additionally, the poor therapeutic response noted with either drug

needs to be studied in the context of the basic underlying etiology, that

can have an important bearing on airway problems.

Contributors: AS: Data collection,

statistical analysis and drafting of manuscript. JM: Concept, study design

and planning, analysis and drafting of manuscript. SS: Study design and

planning, and critical review of manuscript.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None stated.

|

What is Already Known?

• Both epinephrine and budesonide are similar in

efficacy and safety in infective croup.

What This Study Adds?

• Both aerosolized epinephrine and budesonide are

equally effective in their rapid therapeutic response in post-extubation

stridor.

|

References

1. McGovern FH, Fitz-Hugh GS, Edgemon LJ. The hazards

of endotracheal intubation. Ann Otol 1971; 80: 556-564.

2. Anene O, Meert KL, Uy H, Simpson P, Sarnaik AP.

Dexamethasone for the prevention of post extubation airway obstruction: A

prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Crit Care

Med 1996; 24: 1666-1669.

3. Jordan WS, Graves CL, Elwyn RA. New therapy for post

intubation laryngeal edema and tracheitis in children. JAMA 1970; 212:

585-588.

4. Goddard JE, Phillips OC, Marcy JH. Betamethasone for

prophylaxis of postintubation inflammation: A double blind study. Anesth

Analg 1967; 46: 348-353.

5. Pender JW. Endotracheal anesthesia in children:

advantages and disadvantages. Anesthesiology 1954; 15: 495-506.

6. Nutman J, Brooks LJ, Deakins K, Baldesare K, Witte

M, Reed M. Racemic versus L-epinephrine aerosol in the treatment of

postextubation laryngeal edema: Results from a prospective, randomized,

double-blind study. Crit Care Med 1994; 22: 1591-1594.

7. Waisman Y, Klein BL, Boenning DA, Young GM,

Chamberlain JM, O’Donnell R, et al. Prospective randomized

double-blind study comparing L-epinephrine and racemic epinephrine

aerosols in the treatment of laryngotracheitis (croup). Pediatrics 1992;

89: 302-306.

8. Meade MO, Guyatt GH, Cook DJ, Sinuff T, Butler R.

Trials of corticosteroids to prevent postextubation airway complications.

Chest 2001; 120: 464S-468S.

9. Husby S, Agertoft L, Mortenson S, Pedersen S.

Treatment of croup with nebulised steroid (budesonide): a double bind,

placebo controlled study. Arch Dis Child 1993; 63: 352-355.

10. Godden CW, Campbell MZ, Hussey M, Cogswell JJ.

Double blind placebo controlled trial of nebulised budesonide for croup.

Arch Dis Child 1997; 76: 155-158.

11. Fitzgerald D, Mellis C, Johnson M, Allen H, Cooper

P, Van Asperen P. Nebulized budesonide is as effective as nebulized

adrenaline in moderately severe croup. Pediatrics 1996; 97: 722-725.

12. Tellez DW, Galvis AG, Storgion SA, Amer HN, Hoseyni

M, Deakers TW. Dexamethasone in the prevention of postextubation stridor

in children. J Pediatr 1991; 118: 289-293.

13. Kemper JK, Benson MS, Bishop MJ. Predictors of

postextubation stridor in pediatric trauma patients. Crit Care Med

1991; 19: 352-355.

14. Koka BV, Andre JM, Smith RM, Jeon IS, Mackay I.

Postintubation croup in children. Anesth Analg 1977; 56: 502-505.

15. Westley CR, Cotton EK, Brooks JG. Nebulized racemic

epinephrine by IPPB for the treatment of croup. Am J Dis Child 1978; 132:

484-487.

16. Klassen P, Feldman E, Watters K, Sutcliffe T, Rowe

C. Nebulized budesonide for children with mild-to-moderate croup. N Engl J

Med 1994; 331: 285-289.

17. Fogel JM, Berg IJ, Gerber MA, Sherter CB. Racemic epinephrine in

the treatment of croup: nebulization alone versus nebulization with

intermittent positive pressure breathing. J Pediatr 1982;

25: 1028-1031.

|

|

|

|

|