|

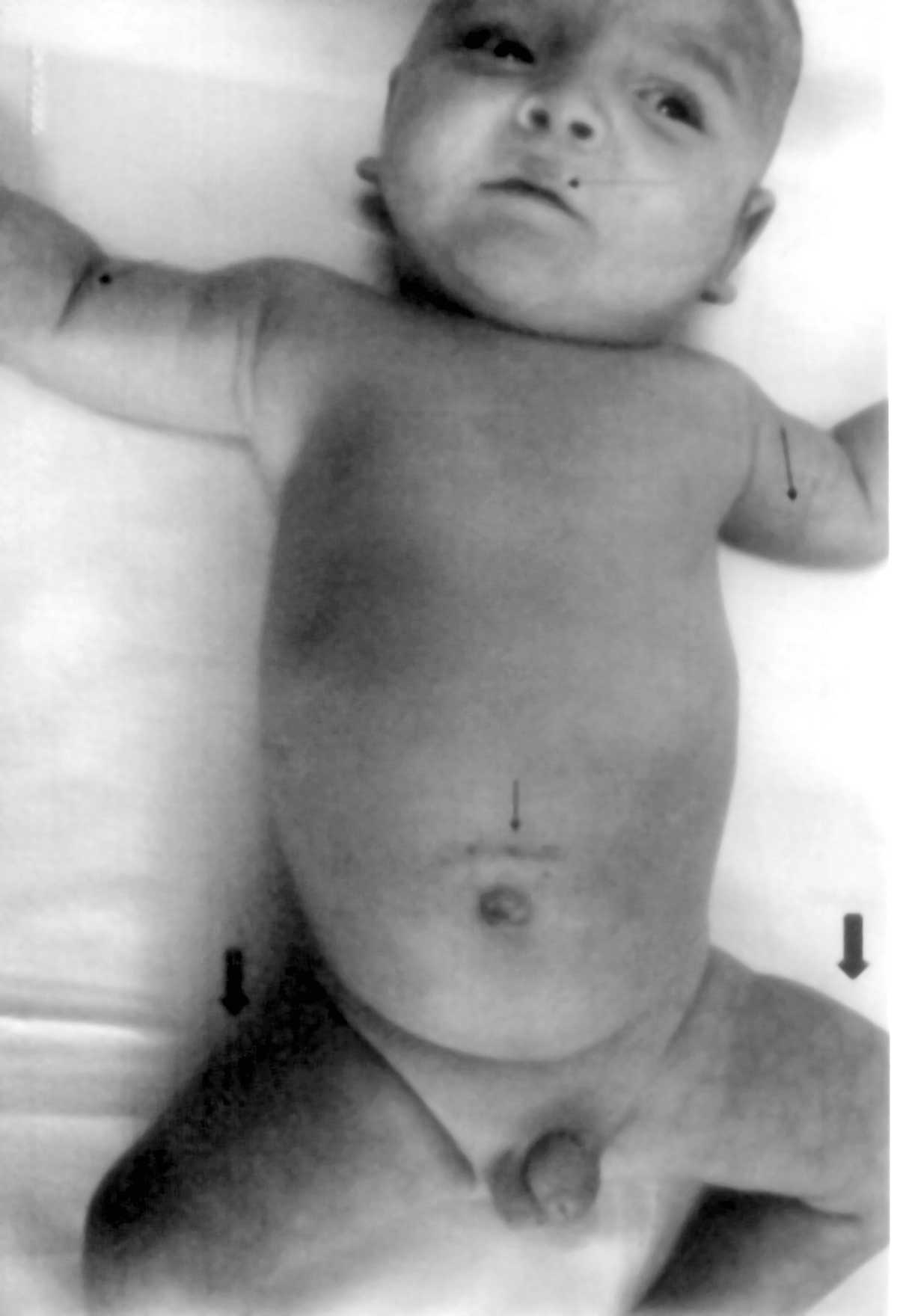

A 5-month-old boy patient was referred to us because of skin problems.

The parents were second cousins. There was no family history of

congenital skin or vascular diseases. He was born premature and

suffered from hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, respiratory distress

syndrome and septic shock. He was kept in the neonatal intensive care

unit for fifty days and had required six cutdown procedures because of

management of life-threatening episodes of septic shock. At the age of

two months, he developed multiple reticuled, blue-violet skin lesions,

midline nevus flammeus along the upper lip, cavernous hemangioma at

the frontoparietal region and the chin (Fig. 1.). The skin

lesions were distributed all over the body especially below umbilicus.

We thought that these features of cutis marmorata telengiectatica

congenital (CMTC) might be connected with the vascular trauma because

of repeated cutdown procedures, although Doppler study of venous and

arterial system was normal. Brain computerized tomography revealed

left hemispheric atrophy, asymmetric dilatation of left lateral

ventricle and calcification at left basal ganglion level.

|

|

Fig. 1. Typical reticulated blue-violet

net-work is evident on the left arm, right and left leg (thick

arrows). Note nevus flammeus of philtrum and upper lip (dotted

arrow) and three cutdown scars (thin arrows).

|

A number of hypothesis have been proposed for the

pathogenesis of CMTC, including environmental factors, autosomal

dominant inheritance with low or variable penetrance, a multifactorial

cause or a lethal gene surviving mosaism, a peripheral neural

dysfunction, and a failure of development of the mesodermic vessels in

the early embryonic stage(1-4). We suggest that a failure of

development of vessels might be because of septic shock and frequently

repeated cut- down procedures. One of the most serious complications

of cutdown procedures is probably arterial thrombosis. And also,

repeated microthrombosis might lead to increased peripheral flow

resistance, which causes a perfusion deficit, and thus explain the

reduced oxygen saturation in the tissues and specific skin problems.

Although, we could not confirm this theory, we presume a functional

malformation at the level of the terminal blood vessels.

Osman Baspinar,

Selim Kervancioglu,*

Departments of Pediatrics,

and *Radiodiagnostics,

Gaziantep University, Faculty of Medicine,

Gaziantep, Turkey.

E-mail: baspinar@gantep.edu.tr

1. Amitai DB, Fichman S, Merlob P, Morad Y,

Lapidoth M, Metzker A. Cutis marmorata telengiectatica congenita:

Clinical findings in 85 patients. Pediatr Dermatol 2000; 17:

100-104.

2. Gerritsen MJ, Steijlen PM, Brunner HG, Rieu P.

Cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita: Report of 18 cases. Br J

Dermatol 2000; 142: 366-369.

3. Devillers AC, de Waard-van der Spek FB, Oranje

AP. Cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenital: Clinical features in

35 cases. Arch Dermatol 1999; 135: 34-38.

4. Mazereeuw-Hautier J, Carel-Caneppele S, Bonafe JL. Cutis

marmorata telengiectatica congenita: report of two persistent cases.

Pediatr Dermatol 2002; 19: 506-509.

|