Introduction

Tracheo-bronchial rupture, due to blunt trauma in

children, is an uncommon injury with a variety of clinical

presentations(1-3). The clinical features even with the major

disruptions can be minimal, delaying the diagnosis in 25 to 68% of the

cases and hence, high index of suspicion is required for diagnosis(1,4).

However, a total absence of initial clinical signs and symptoms is

unusual. We present a case of right main bronchus injury with absence of

initial clinical features resulting in a delayed diagnosis.

Case Report

An 8-year-old, 13 kg boy sustained blunt trauma with

an iron door falling on his chest and pinning him to the ground. There

was no history of head injury, respiratory distress, subcutaneous

emphysema or hemodynamic instability following trauma and the chest

radiograph did not reveal pneumothorax or pneumomediastinum. He was

given pain relief and did not require hospitalization. The child

remained well for 3 months before he started having recurrent cough and

occasional difficulty in breathing on exertion. The patient was treated

symptomatically for another 5 months in a peripheral hospital before

referral to our center. The clinical examination revealed a stable child

with no respiratory distress. The chest wall on the right side was

slightly depressed. The trachea and heart were shifted to the right and

the air entry was poor in the right lower half of the chest. An x-ray

of the chest revealed collapsed right lung near the right dome of the

diaphragm and hyper-inflation of the left lung. The underlying bony cage

was normal. An ultrasonography of the chest showed minimal fluid in

right thoracic cavity. The echocardiography was normal. The CT scan of

the chest showed collapsed right lung lying in the right para-vertebral

gutter and hyper-inflated left lung with herniation of the apex of left

lung to the opposite side. The right main bronchus showed abrupt cut-off

with no evidence of extrinsic compression or endo-bronchial lesion

including foreign body thereby suggest-ing a bronchial injury (Fig. 1).

Bronchoscopy revealed normal trachea and bronchial take-off on both the

sides but the right main bronchus was completely occluded at 1.5 cm from

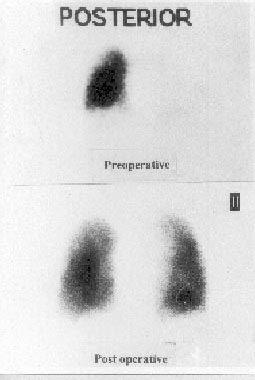

the carina. The origin of upper lobe bronchus was not seen. A perfusion

scan of the lung showed negligible perfusion (only background activity)

to the collapsed right lung (Fig. 2).

|

|

Fig. 1. CT scan of chest showing herniation

of hyperinflated left lung and atelectatic right lung in right

paravertebral gutter. |

The endotracheal tube for general anesthesia was

manipulated into the left main bronchus. The patient underwent right

postero-lateral thoracotomy. The right main bronchus was found to be

transected at about 1.5 cm from the carina, and the other end was

somewhat buried into the collapsed lung near its hilum. The gap between

the two ends was approximately 4 cm. The distal end was dissected out

from the hilar structures and opened. After suction of the mucus, the

collapsed lung could be inflated by inserting a separate endotracheal

tube into the distal bronchial end. An end-to-end anastomosis was

performed with interrupted sutures of 5-0 Vicryl in a single layer.

Post-operatively, the patient recovered well and did not require

ventilation. A perfusion scan four months later showed near-normal

expanded lung with increased perfusion (Fig. 2). The chest

radiograph and the CT scan showed near normal lung expansion and the

patient had developed normal exercise tolerance.

|

|

Fig. 2. Radionucleide perfusion scan showing

majority of the perfusion going to the left lung preoperatively

(upper scan) and near equal perfusion of both the lungs 4 months

after repair (lower scan). |

Discussion

The patients with traumatic rupture of tracheo-bronchial

tree exhibit well-recognized signs and symptoms of bronchial transection

such as shortness of breath, mediastinal and subcutaneous emphysema,

hemoptysis, pneumothorax, atelectasis, persistent air leak and failure

to expand the lung with thoracostomy tube drainage. The lung drops below

the level of the carina if the bronchus is completely transected and it

is a pathog-nomonic radiological sign(1,5,6). Various mechanisms of

injury are compression of tracheobronchial tree between the sternum and

the vertebral column resulting in distraction of the carina, shearing of

bronchus by rapid deceleration and rapid increase in tracheo-bronchial

pressure as a result of crush injury with a closed glottis(1,5).

The bronchial injury may be sealed by the

peribronchial tissues and the patient survives the initial damage but

absence of air leak at presentation is unusual and rare(6,7). However if

the tear is in the mediastinal part of the main bronchus or trachea,

pneumothorax may not occur and only mediastinal air will be seen(3,5).

In cases, which have no pleural communication, ventilation may proceed

through the torn area and the diagnosis is frequently delayed(5).

Bronchoscopy is mandatory to make the diagnosis of bronchial transection

when such a lesion is suspected even with minimal clinical and radio-

logical symptoms(1-3,6). Granulation tissue invades the area over next 1

to 3 weeks after injury. Incomplete obstruction will lead to restriction

of normal removal of the secretions and infection. However, if the

bronchial communication snaps suddenly and completely, there is no

aeration, which protects the lung from the air-borne sepsis and sterile

mucus collects inside the atelectatic lung(5). The possibility of

bronchial repair should be entertained even in the cases recognized long

after injury(6). The prognosis depends upon the time interval between

the diagnosis and treatment, associated vessel injury and the condition

of the distal transected lung(6). Expansion and deflation of the lung on

the operation table, before repair, demonstrates compliance and

elasticity of the atelectatic lung and the likelihood of regaining a

good lung growth in the postoperative period. When repair is

impractical, resection is indicated to avoid infection and pulmonary

vascular shunt(1).

The vascularity of the chronic atelectatic lung is a

concern especially in the cases, which are diagnosed late(8). The

radionucleide perfusion scan is a simple, efficient, non-invasive

modality to evaluate the circulation of chronically collapsed lung and

can be used repeatedly to assess the immediate and delayed response to

the surgical repair(4,5).

In our case, the initial symptoms were subtle and the

child did not show the air leak either clinically or radiologically, to

suggest the presence of tracheo-bronchial disruption. Such near total

absence of clinical symptoms has been unusual in the pediatric

population. The diagnosis is usually delayed if air ceases to leak from

the chest drainage tube, which our patient did not require. However,

persistent atelectasis of the lung in our patient aroused the suspicion

of a bronchial injury and bronchoscopy confirmed it. Hence, significant

bronchial injuries may occur in the absence of usual initial symptoms.

Therefore, the patients of obvious chest trauma should be on follow up

in the immediate post-injury period for detecting these lesions to avoid

unnecessary morbidity and possible mortality.

Contributors: Study concept and design JKM, KLNR,

PM, BRM. Analysis and interpretation of data: JKM, KLNR, PM, BRM.

Drafting of manuscript: JKM, PM, KLNR, Guarantor of the manuscript: KLNR.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None stated.