|

Haemophilus influenzae

type b (Hib) bacterium was estimated to have

caused 8.1 million cases of serious Hib diseases, and 371,000 deaths

globally in the year 2000 [1]. In India, an annual estimated 2.4 to

3.0 million cases and 72,000 deaths in under-5 children were

attributed to Hib diseases [1, 2]. Safe and effective vaccines to

prevent Hib diseases have been available for nearly two decades and

are being used globally. The National Technical Advisory Group on

Immunization (NTAGI) in India recommended the introduction of Hib

vaccine in the Universal Immunization Program (UIP) in 2008 [2].

From December 2011, Hib vaccine in combination with diphtheria,

pertussis, tetanus and hepatitis B has been introduced in UIP in

Kerala and Tamil Nadu states. A comprehensive technical review on

Hib diseases and vaccines was published in 2009 in this journal [2].

This paper provides an update on global Hib vaccine use, and reviews

the process and steps undertaken in India to introduce Hib-containing

pentavalent vaccine in Kerala and Tamil Nadu.

Hib Diseases

It is estimated that mortality due to Hib disease

contributes 4% of all annual under-5 deaths in India [1, 3, 4]. The

fastidious nature of the Hib bacterium and poor laboratory

infrastructure in developing country settings such as India makes

the diagnosis of Hib diseases and calculation of disease burden

extremely difficult. Moreover, a combination of limited access to

health services and poor health-seeking behavior by rural

populations results in many affected children never having the

opportunity of being correctly diagnosed or receiving appropriate

care [5]. Even for those children who do reach health facilities,

the increasing prevalence of antibiotic-resistance makes treatment

difficult [6, 7].

Hib Vaccines and Their Introduction

Hib vaccines are available in liquid and

lyophilized formulations and presented in monovalent format or

combined with other antigens such as DPT and/or hepatitis B

antigens. Hib vaccines have been shown to be cost-effective in both

developed and developing country contexts and are in use for more

than two decades. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends

that Hib vaccines be included in routine infant immunization

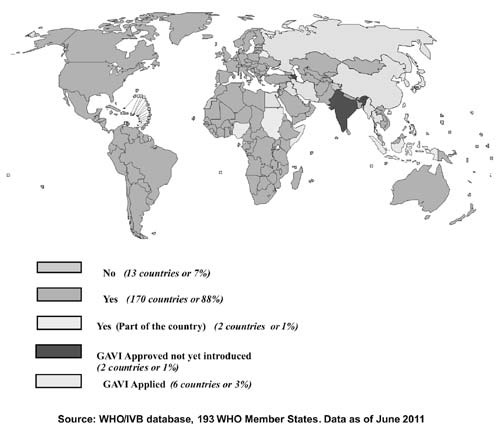

programs of all countries [7]. By June 2011, Hib vaccine, in various

formulations, was included in the national immunization program of

170 countries in all regions of the world [8].

Hib vaccination also reduces nasopharyngeal

colonization with the bacterium, resulting in further reductions of

Hib disease incidence. In addition to the effects directly

attributed to the vaccine, there are important indirect effects

associated with Hib vaccines. Indirect benefits include herd

immunity and reductions in antibiotic resistance by preventing

disease and inappropriate use of antibiotics. These benefits have

been amply demonstrated by the post-introduction studies where near

elimination levels of Hib disease have been reached;

near-elimination of the disease occurred in both industrialized and

developing countries, even countries with moderate to low

immunization coverage rates [9-12].

Decision-making

In April 2008, the NTAGI Sub-committee on Hib

vaccine reviewed available literature and information related to

disease burden in India, vaccine availability, safety and efficacy,

and cost-effectiveness. Based on this information, the Sub-committee

recommended that Hib-containing pentavalent vaccine should be

introduced in the country [2,3]. In a subsequent NTAGI meeting held

in June 2008, the Sub-committee recommendations were discussed.

Based on the cumulative weight of supporting evidence, the

Sub-committee’s recommendation to introduce Hib-containing

pentavalent vaccine was endorsed [3]. Importantly, the Indian

Academy of Pediatrics (IAP) had already recommended in 2006 the use

of Hib vaccine for all children [13]. The use of Hib vaccines in the

private sector is widespread in India for almost a decade. Following

the recommendation of NTAGI, the Ministry of Health and Family

Welfare (MoHFW), Government of India (GoI), decided to introduce the

vaccine initially in two states.

Strategy for Vaccine Introduction

Government of India has introduced Hib as liquid

pentavalent vaccine (LPV) combined with DPT and HepB in 10-dose

presentation. The use of combination formulation has certain clear

programmatic advantages. First, the number of injections per

completed schedule will be less, consequently requiring fewer

syringes and generating less potentially hazardous sharps waste. In

addition, cold chain space will be saved as a single vial of LPV

replaces DPT and Hep B vials. LPV has been recommended for all

infants and will be given in a 3-dose schedule. The first dose is

given at 6 weeks of age or older followed by dose 2 after a gap of

at least 4 weeks and a gap of at least 4 weeks before dose 3 (Table

I). The vaccine is offered to all children younger than 1

year of age and the booster dose is not recommended in UIP in India

[2, 14].

TABLE I Immunization Schedule following Pentavalent Vaccine Introduction

|

Age |

Current schedule |

After introduction of

Pentavalent vaccine |

|

At Birth |

BCG, OPV-0, HepB-Birth dose |

BCG, OPV-0, HepB-Birth dose |

|

6 weeks |

OPV-1, DPT-1, HepB1 |

OPV-1, Pentavalent-1 |

|

10 weeks |

OPV-2, DPT-2, HepB2 |

OPV-2, Pentavalent-2 |

|

14 weeks |

OPV-3, DPT-3, HepB3 |

OPV-3, Pentavalent -3 |

|

16-24 months |

DPT-B1, MCV2, OPV-B1 |

DPT-B1, MCV2, OPV-B1 |

|

5-6 year |

DPT-B2 |

DPT-B2 |

To facilitate and ease program implementation,

Government of India policy states that LPV will be given to a

progressive birth cohort whereby all children who present for their

first dose of DPT (DPT 1) will be provided their first dose of LPV

(LPV 1). Infants who had already initiated their schedule of DTP +

HepB will complete the DPT and HepB vaccines schedule. In addition,

monovalent Hepatitis B vaccine will continue to be used for

birth-dose and DPT vaccines will continue to be used for 16-24

months and 5-6 years of age booster doses [2, 14].

Preparing for Vaccine Introduction

The operational guidelines and frequently asked

questions for the introduction of LPV in UIP were developed and

provided to Kerala and Tamil Nadu states for wider dissemination,

several months prior to the initiation of LPV use. State

immunization program managers were sensitized on the strategies and

principles of LPV introduction during a National level UIP review

meeting held in May 2011 in New Delhi. In addition, LPV introduction

training materials were produced for medical officers and health

workers.

Training and sensitization within states then

followed a cascade format. State level orientations and training

workshops were held and attended by district immunization officers,

medical college faculty and other stakeholders. District

authorities, program managers, and PHC-block medical officers were

sensitized. In turn, block medical officers trained frontline health

workers on key aspects related to LPV and its introduction.

Representatives of professional associations, such as IAP Indian

Medical Association (IMA), and other stakeholders were also

sensitized at various levels.

In synergy with trainings, information, education

and communication (IEC) material including frequently asked

questions, were prepared in local languages and widely disseminated.

A media-sensitization workshop on Hib diseases and vaccination was

conducted in each state just prior to LPV introduction. The program

was launched by the State Ministers of Health and other senior

health department officials in Kerala and Tamil Nadu.

Capitalizing on Opportunity

Lessons from the introduction of Hepatitis B

vaccine in 10 states of India in 2007-08 illustrated the

immunization system strengthening opportunities that introducing a

new vaccine affords. Likewise, the introduction of LPV has been used

to strengthen Kerala and Tamil Nadu immunization systems by

training/re-training health personnel on proper injection

techniques, assessing and correcting existing cold chain problems,

improving program monitoring and supervision, and enhancing

reporting of adverse events following immunization. In addition,

pre-introduction training phase emphasized the importance of

maintaining sufficient stocks of monovalent Hepatitis B and DPT

vaccines to ensure the application of birth-dose and DPT booster (at

16-24 months and 5-6 years of age).

|

|

Fig. 1 Countries which have

introduced Hib vaccine in the National Immunization Program.

|

Moreover, the introduction of Hib-containing

pentavalent vaccine offers poorer families the opportunity to

provide the same life-saving protection to their children as

wealthier families who can afford vaccine services in the private

sector. Therefore, the introduction of Hib vaccine, free of cost in

the government system, helps to ensure equity in health service

availability – a stated objective of India’s National Health Policy

[15].

From a public health perspective, this is not a

trivial issue: Hib is one of the leading cause of bacterial

meningitis in India and a major cause of childhood pneumonia, the

largest killer of Indian children less than 5 years of age. It is

estimated that Hib disease prevention through vaccine use has the

potential to reduce India’s under-5 mortality rate by 4 percentage

points. The introduction of LPV in India is a major milestone and a

step forward to accelerate child survival in India, and progress

towards achieving national health goals and Millennium Development

Goal 4.

Competing interests: None stated.

Disclaimer: The view expressed in this paper

are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the UNICEF

and WHO.

References

1. Watt JP, Wolfson LJ, O’Brien KL, Henkel E,

Deloria-knol M, McCall N, et al. Burden of disease caused by

Haemophilus influenzae type b in children younger than 5

years: global estimates. Lancet. 2009; 374: 903-11.

2. Subcommittee of NTAGI. NTAGI subcommittee

recommendations on Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib)

vaccine introduction in India. Indian Pediatr. 2009;46:945-54.

3. Government of India. Operational guidelines:

Introduction of Hib as Pentavalent Vaccine in Universal Immunization

program in India. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Govt. of

India, New Delhi, 2011.

4. United Nations Children’s Fund. Level and

Trends in Child Mortality: Report 2010. UNICEF and WHO, New York;

New York and Geneva: 2010.

5. National Family Health Survey (NFHS)

2005-2006, International Institute of Population Sciences, Mumbai,

India. Available at www.nfhsindia.org. Accessed on March 1,

2012.

6. World Health Organization. Introduction of

Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine into immunization

programmes. World Health Organization, Geneva, 2000.

7. World Health Organization. WHO Position Paper

on Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccines. Weekly

Epidemiol Rec. 2006;81:445-52.

8. World Health Organization. WHO/ IVB database

of 193 WHO member states, as of June 2011

9. Cowgill KD, Ndiritu M, Nyiro J, Slack MP,

Chiphatsi S, Ismail A, et al. Effectiveness of Haemophilus

influenzae type b conjugate vaccine introduction into routine

childhood immunization in Kenya. JAMA. 2006;296:671-8.

10. Lee EH, Lewis RF, Makumbi I, Kekitiinwa A,

Ediamu TD, Bazibu M, et al. Haemophilus influenzae

type b conjugate vaccine is highly effective in the Ugandan routine

immunization program: a case-control study. Trop Med Int Health.

2008;13:495-502.

11. Baqui AH, El Arifeen S, Saha SK, Persson L,

Zaman K, Gessner BD, et al. Effectiveness of Haemophilus

influenzae type b conjugate vaccine on prevention of pneumonia

and meningitis in Bangladeshi children: a case-control study.

Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:565-71.

12. Watt JP, Levine OS, Santosham M. Global

reduction of Hib disease: what are the next steps? Proceedings of

the meeting Scottsdale, Arizona, September 22-25, 2002. J Pediatr.

2003;143: S163-87.

13. IAP guide book on immunization , IAP

Committee on Immunization 2007-2008, Indian Academy of Pediatrics,

Jaypee Brothers, New Delhi

14. Government of India. Pentavalent Vaccine.

Guide for Health Workers. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare,

Govt. of India, New Delhi, 2011.

15. National Health Policy 2002 (India), Ministry

of Health and Family Welfare. Available at http://mohfw.nic.in/nrhm/documents/national_health-policy_2002.pdf.

Accessed on March 1, 2012.

|