octors are expected to

consistently exhibit professional attitudes, behaviour, values and

ethics in their practice. Professionalism is an important component of

medicine's contract with society. The concept of the profession of a

doctor has changed considerably with the times. Previously, doctors were

granted autonomy by the community, with the belief that they would place

the welfare of their patients before their own. However in contemporary

society, this autonomy has been challenged by the altered public

perception of the role of the doctor. Their behaviour is now observed

and scrutinized more closely by the media. Doctors' own attitudes

towards their vocation have also changed [1,2].

Though a small minority of professionals exhibit

inappropriate professional behaviour, they end up receiving

disproportionate attention, maligning the entire profession. Medical

errors, adverse outcomes, malpractice and inappropriate behaviour result

when doctors do not adhere to guidelines, have difficult workplace

relationships, find themselves inadequate in communication,

collaboration and transfer of information, or suffer from low morale

[3].

Studies from the West have shown that students who

demonstrate unprofessional behaviour during their undergraduate and

postgraduate education are more likely to be found guilty of

unprofessional actions by the monitoring boards after they graduate

[3,4]. Thus, the need to include teaching and assessment of

professionalism in the formal curricula for undergraduate and

postgraduate medical training has been globally acknowledged. The

Medical Council of India (MCI), the custodian of medical education in

the country, has not even explicitly mentioned professionalism in the

Graduate Medical Education Regulations [5]. The Postgraduate Medical

Education Regulations 2000 cursorily mention that their goal is to

produce competent specialists "who shall recognize the health needs of

the community, and carry out professional obligations ethically and in

keeping with the objectives of the national health policy", but do not

elaborate this further. The focus is on acquisition of theoretical

knowledge, practical and clinical skills, communication skills, and

research acumen [6]. Further, there is no consensus on what is meant by

professionalism or how it should be integrated into the curriculum.

Assessment of professionalism is an even more contentious territory as

it is such an intangible entity.

Defining Professionalism

Professionalism is a theoretical construct, more

easily described in lofty idealistic terms than by observable

behaviours. There is also much variation in what 'professionalism' means

across different countries. Epstein and Hundert, in 2002, defined

professional competence as "the habitual and judicious use of

communication, knowledge, technical skills, clinical reasoning,

emotions, values, and reflection in daily practice for the benefit of

the individual and community being served’’ [7]. The Royal College of

Physicians, UK, defines professionalism as "a set of values, behaviours,

and relationships that underpin the trust the public has in doctors"[8].

The American Board of Internal Medicine identified the key elements of

professionalism as: altruism, accountability, duty, excellence, honor,

integrity and respect for others [8]. The medical educationists from

Netherlands defined professionalism in terms of observable behaviours to

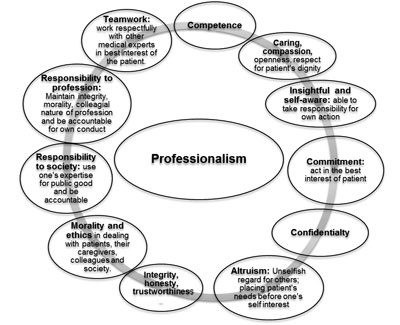

make assessment feasible [8]. In an effort to make these elements more

explicit, a faculty development initiative tried to build consensus by

defining some of the core attributes of professionalism. Some of these

are displayed in Fig. 1 [9].

|

|

Fig. 1 Core attributes of

professionalism,

|

Evolving definitions of professionalism perhaps

reflect the place it is accorded in medical training. The elements in

initial definitions are easy to identify but difficult to measure as

learning outcomes. The subsequent definitions include behaviours that

are observable, to some extent measurable, and hence amenable to

assessment and inclusion as a core curricular component.

The societal and cultural value system influences the

perception and interpretation of professional behaviour of a physician.

Naturally, while everyone agrees on the core elements of

professionalism, a consensus on a culturally appropriate global

definition appears to be lacking. Therefore, it is imperative for each

country and every institution to develop its own definition of

professionalism, according to the societal norms of the times, and

identify its core elements.

Though no Indian publication dedicated to defining

professionalism in Indian context could be found on literature search,

there have been recent meetings and conferences addressing this issue.

One of the authors (TS) was a keynote speaker at a deliberation on

Professionalism held at Karamsad in April 2013 where these aspects were

discussed in depth. Also, a workshop and meeting of the Indian

physicians from all over the world (Global Indian Doctors) was held in

Kolkata in January 2014 to address the worrisome decline in practice of

professionalism and ethics. They noted the critical role of education

and mentorship in inculcating right values from the start of medical

training [10]. A welcome beginning was also made by the MCI in form of

proposed new regulations for Graduate Medical Education 2012 that

mentioned some aspects of professionalism as a core competency for

Indian medical graduates.

Teaching And Learning Professionalism

Professionalism is not a single skill, but a

multi-dimensional competency construct with several component skills. A

combination of teaching-learning methods is essential for imparting

training in professionalism. It is worthwhile to address the 'why, what,

who, where, when and how' of teaching professionalism before

incorporating it into the curriculum [11].

Why does professionalism need to be taught and

assessed?

For years, the development of professional values in

a doctor was taken for granted and it perhaps held true in the earlier

apprenticeship model of physician training. With changing models of

physician training, this view has changed. As professionalism is so

intrinsic and integral to the medical profession, it should be an

explicit part of the medical curriculum. It is now globally agreed that

professionalism is a core competency for physicians and cannot be left

to informal means to be imbibed [8,12]. It is well known that what is

not assessed is not valued by students. Therefore, institutions need to

develop written criteria about what needs to be taught and assessed.

What should be taught and learnt?

As mentioned earlier, it is important for each

institution to define professionalism in its own context. The faculty as

well as students should have a clear understanding of the traits,

characteristics and qualities that contribute to professionalism. A

written statement of curricular outcomes, content (such as ethics,

decision making/moral reasoning, humanism, empathy, communication), and

an explicit list of knowledge, skills and attitudes guards against

delivering conflicting messages to students [13]. Developing an

institutional curriculum for professionalism with a feasible and

acceptable blueprint for teaching-learning and assessments is also

likely to instil a sense of ownership in the faculty, and hence

facilitate effective delivery of this curriculum [14].

Who should teach and be taught?

Without doubt, professionalism should be included in

the formal curriculum of both undergraduate medical students and

postgraduate trainees [9,13]. At the same time, the traditional place of

professionalism in the hidden and informal curriculum deserves equal

attention. The behaviour of faculty must reflect the attributes of

professionalism as endorsed by the institution rather than be at

conflict with it. For this, the sensitization and training of faculty in

teaching learning and assessing professionalism is of key importance.

The students' training will enable them to observe and imbibe

appropriate attitude and behaviour.

When and where should professionalism be taught?

Teaching and learning of professionalism cannot be

confined to a certain stage of medical training but has to be explicitly

'woven into the fabric' of entire undergraduate curriculum and also the

postgraduate training [15]. Inculcation of professional values should

begin at the time of entry into medical school. Cruess and Cruess

suggest 'continuity' and 'incremental approach' in teaching-learning and

assessing professionalism in medical schools [16]. They further propose

that with an initial strong cognitive base, 'stage appropriate'

educational activities (including assessment) should be devised. Faculty

must also utilize the opportunities at workplace to reinforce the

correct behaviour and allow the students to practice what they have

learnt during the formal training sessions in professionalism. Thus

training should focus not only on inculcating the core aspects of

professionalism, but also on making the student a self-motivated and

self-directed learner.

How should professionalism be taught?

Many of the core attributes of professionalism are

related to soft skills. Some common aspects that contribute to bringing

about attitudinal or behavioural changes and are integral to planning

educational activities for professionalism are outlined below:

(i) Motivation (self-driven;

intrinsic): Students must imbibe the importance of the desired

change in behaviour for it to be a driving force.

(ii) Observation of role models:

Teachers have always been role models for students and their

positive as well as negative behaviour patterns are likely to be

imbibed by the students (informal and hidden curriculum). The

trainees need orientation and a cognitive base to be able to

discriminate between good and poor role modelling [17].

(iii) Continued stimulus to be thinking

about these aspects of being a physician rather than in spurts

occasionally.

(iv) Feedback: Timely and effective

feedback on own behaviour received from friends, colleagues, peers,

seniors with positive reinforcement of desired behaviour as well as

corrective suggestions for improvement.

(v) Reflection and reflective practice:

Very simply expressed as ‘mental processing with a purpose or

anticipated outcome’, this is the key to attitudinal change [8]. One

could reflect on an experience or a behaviour or on feedback

received. 'Reflection on action' is most important and can be well

encouraged by providing situations and experiences during the course

of training [15].

(vi) Extrinsic motivation: Reward

or appreciation related to behaviour. Assessment works by way of

feedback as well as by providing an extrinsic motivation.

Teaching professionalism involves several intricacies

(Box I). The teaching-learning methods that may be

utilized are:

• Interactive lecture and brainstorming:

These can help in initial sensitization and in introducing students

to the concept. A good cognitive base with clarity on definitions

and concept in the initial stages of training will enable the

students to make the most out of experiences and other educational

activities in later stages of training [18].

• Clinical scenarios or case vignettes:

These could be designed to focus on various aspects of

professionalism, such as, honesty with patients, patient

confidentiality, maintaining appropriate behaviour with patients and

their caregivers, active listening etc. Small group discussions or

individual exercises that involve responding to such scenarios

compel the students to reflect on these aspects of a doctor's

working [18].

• Reflective exercises: These could be

discussions based on actual situations that arose during work,

sharing of own experiences by the trainee or based on what they

observed. Dedicated time needs to be put aside for this activity

[15].

• Feedback: Provision of timely and

effective feedback to the trainee is a powerful way of guiding the

development of professional values. The feedback should be specific,

based on an observed incident/behaviour and be given along with a

feed forward for appropriate behaviour in future in such situations.

The importance of observing in authentic workplace setting and

providing feedback based on it cannot be overemphasised. Assessment

methods such as mini-clinical evaluation exercise and directly

observed procedural skills (DOPS) have 'feedback' built into the

assessment process and are therefore excellent teaching methods as

well.

• Portfolios: Student portfolios, in

contrast to a log-book, include reflections of the student in his

own words. This is another way of compelling the trainees to

think-back about their observations and experiences, and thus

inculcate a habit of self-development based on reflective thinking

[19].

• Role models: Students knowingly or

unknowingly imbibe the professional behaviour of teachers. So it is

of utmost importance that teachers are sensitized to their role as a

'role model' to the students and that they are consciously aware of

the same at all times [17].

• Art-based interventions: Use of arts in

medical education to foster a better understanding of patients'

perspectives is also being utilized as a strategy for developing

professional values in some institutions. This approach not only

develops trainees as better communicators, but also encourages them

to explore own feelings [20]. The 'Theatre of the Oppressed'

initiative by the medical humanities group of University College of

Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India is an example of this effort in

India.

|

Box I Strategies to Teach Professionalism |

•

|

Sensitization: Orienting students to the concept of

professionalism and its importance so that they recognize it as an

essential component of physician training and subsequent practice. |

•

|

Immersion: Expose them to situations (hypothetical or real) that

force them to think on these lines. |

•

|

Provide time and opportunities for reflection: Following

exposure to situations or experiences, it is equally important to

provide a conducive environment, create opportunities and provide

dedicated time to reflect upon them. |

In summary, a structured stepwise approach in

planning a training program using a judicious combination of various

methods in an appropriate sequential or simultaneous manner is

desirable.

Faculty development in teaching and learning of

professionalism serves two main purposes. One, faculty are sensitized to

their role as 'role models' to students and the imbibed curriculum.

Second, it encourages them to consciously adopt one or more methods for

imparting professional values to the students [9]. In India, it may be a

good idea to include a module on professionalism in faculty training

sessions by the Medical education units.

An obvious cognizance of professional behaviour by

authorities (rather than appreciation of only clinical competence) can

be an effective way of setting the expected standards [14]. Positive

acknowledgement of exemplary professional behaviour and punitive action

for unprofessional behaviour will drive home the message well.

Assessment of Professionalism

Assessment is said to be the driving force behind

learning. It directs and guides learning, and provides a degree of

importance to a given area. Professionalism is no exception. Without a

system to assess professionalism, acquisition of professional values

will be rated low in priority [13]. Furthermore, without assessment,

teachers and students will have no yardstick to gauge the level of

learning [21].

There are several impediments to the assessment of

professionalism. The first is the common belief that "professionalism is

caught and not taught". There is no evidence for or against this belief

so far. However, by saying that professionalism is not taught, we accept

the fallout of this idea that this learning is haphazard, not guided by

any specific objectives and not amenable to assessment. This approach is

likely to promote negligence of professionalism in assessment planning.

The second issue is the cultural acceptance (or

non-acceptance) of unprofessional behaviour. In India, so far,

unprofessional behaviour has been viewed rather leniently by society. In

our society, it may be difficult to penalize a student on the basis of

deviations from professional behaviour. Unless society demands strict

professional behaviour from doctors, lapses in professionalism may be

difficult to control. For this, to be effective, we need to identify and

respond appropriately to each unprofessional behaviour [3].

The third issue is our obsession with objectivity in

assessment. Given the present state of our understanding, we may not be

able to objectively measure professionalism. However, we could take

steps to blunt the effect of subjectivity (e.g. by increasing the

number of tests and raters, or by faculty training).

Lastly, behaviour is greatly influenced by the local

context and organizational factors. What is considered professional in

one organization may be considered unprofessional in another [22]. This

explains why we have not been able to develop standardized tools to

assess professionalism. Further, when an institution or a faculty member

in an institution demonstrates unprofessional behaviour and goes

unpunished, then it may really be difficult to penalize students for

similar behaviour. Despite these odds, it is prudent to assess

professionalism.

Many of issues of professionalism faced by doctors or

patients relate to their conduct rather than to their competence. There

is evidence to suggest that since professionalism is learnt, it can be

moulded in a particular direction. This teaching - as argued above -

cannot happen without a supportive assessment. Like assessment of

knowledge and skills, assessment of professionalism has be both,

formative and summative. However, such assessment should be defensible

[23].

What should be assessed under professionalism?

The best way to answer this question is to use

Miller's pyramid and assess each level as appropriate to the stage of

the training (Table I). Thus new students should be

assessed to find out what they know about professionalism, while final

year students and interns may be assessed at the 'shows' and 'does'

levels [22]. It needs to be emphasized that the base of knowledge should

not be undermined, because the students have to first know "what is

professionalism'', before they can demonstrate professional behaviours

in different contexts. This is not to say that assessment should be

limited only to written tests. Assessment should include behavioural

aspects as well.

TABLE I: Tools Used for Assessment of Professionalism

Level of Miller's pyramid

|

Tools

|

|

Does |

Multi Source Feedback (MSF), healthcare outcomes, critical

incident report |

|

Shows |

Observed real or standardized patient encounter (m-CEX; PMEX;

OSCE) |

|

Knows how |

Reflective/narrative portfolio, Case based discussion |

|

Knows |

Multiple Choice Questions (MCQ)/ Short Answer Questions (SAQ)/

Vignettes with professional conflicts |

|

M-CEX-Mini clinical evaluation exercise;

PMEX-Professionalism mini evaluation exercise; OSCE-Objective structured

clinical examination. |

As far as possible, assessment of professionalism

should take place in actual work settings i.e. Workplace-based

Assessment (WPBA) rather than in the controlled artificial settings of

formal examinations [19]. At this juncture, issues of reliability of

workplace based assessment are likely to be raked. However, going by the

experience of using individual tools of WPBA, as well as the composite

program - it should be possible to get fairly reliable results by having

6-8 assessments per year by different assessors [24]. In the beginning,

for several years, such assessments will happen only for formative

purposes. This is useful, as here one does not aim for a very high

reliability. Experience and faculty training will also help to improve

the reliability of such assessments [25].

Vague definitions and lack of unanimous standards may

make the assessment of professionalism challenging. Additionally, some

teachers may be hesitant to give negative ratings, while others may tend

to inflate summative ratings (like what happens with internal assessment

now). However, these kinds of issues should not be taken against

professionalism, as we happily accept the assessment of knowledge and

skills by the same teachers, many of whom are likely to be as much

influenced by the conflict in the role of a teacher and an assessor.

It may be worthwhile to relook at the concept of

utility of assessment, which is a notional concept and is represented as

a product of its validity, reliability, feasibility, acceptability and

educational impact [26]. Assessments which are low on one parameter can

still be very useful by being high on others. Even though numerical

reliability of professionalism assessment might be low, its educational

impact can be fairly high. Relative importance to various attributes of

assessment should be guided by purpose of assessment rather than by a

pursuit of objectivity.

Tools for assessing professionalism

Professionalism is a multi-dimensional concept and no

single tool may be able to capture it in entirety. A number of tools

have been developed for assessing professionalism (Table I).

These include observing patient encounters (mini-CEX, professionalism

mini assessment tool PMEX, standardized direct observation tool);

simulations (OSCE using standardized patients); reporting of

unprofessional incidents (critical incident method); paper and pencil

tests (MCQs, critical incident reports); observer ratings (multi source

feedback, global ratings); self-reported scales and patient satisfaction

surveys [14,19]. We need to select the appropriate tools from this

toolkit to suit our purpose.

Most of the tools mentioned above have been described

in an earlier paper on WPBA [27]. However, PMEX needs some elaboration.

It is a structured observation tool and consists of 21 items, each of

which is rated on a 4 point scale (unacceptable, below expectations, met

expectations and exceeded expectations) [28]. In addition, it has space

for recording of an incident which has shown a clear breach of

professional boundaries. The assessment is discussed with the trainee,

who signs the form at the end of this discussion. The forms become a

part of the learning portfolio and can be used to show the development

of professionalism over a period of time [23]. Factor analysis has

confirmed that it assesses four important factors viz. doctor-patient

relationship, reflection, time management and inter-professional

relationship. A generalizability coefficient of 0.82 (SEM 0.08) is

attainable by 12 forms [28].

Assessment of professionalism needs to be linked to

the overarching assessment of knowledge and skills. While it usually

remains formative, it may need to be made summative, especially at

decision points (e.g. graduation). Compilation of data over a period of

time should help students to attempt to acquire professional values in

areas found lacking and also help teachers to take remedial action.

Irrespective of which tool is used for assessment of professionalism,

the basic premise remains the same i.e. direct observation in authentic

settings followed by feedback and an opportunity to reflect. While there

may not be a consensus on the best tool for assessing professionalism,

there is agreement on the fact that without solid assessment tools,

questions about the efficacy of approaches to educating learners about

professional behaviour will not be effectively answered [24].

A model blueprint for learning and assessing

professionalism in the Indian scenario (for undergraduates) is proposed

in Table II. It is possible to incorporate assessment of various

elements of professionalism in the existent internal assessment

programs, and its reliability can be improved by adopting the Quarter

model of In-training Assessment [29].

Conclusions

Professionalism is integral to the medical profession

and it should be an explicit part of the medical curriculum. Each

country and institution needs to develop its own definition of

professionalism, according to the societal norms of the times and

identify the core elements of professionalism. A judicious combination

of teaching and learning methods need to be incorporated in a

longitudinal manner using a stepwise approach to teach professional

values to students of all levels. Assessment of professionalism needs

priority for it to be taken seriously. Assessment of professionalism is

best done in authentic workplace-based settings, where supervisors have

an opportunity to provide feedback after direct observation of students

and allow them a chance to reflect on their behaviour.

1. Sohl P, Bassford HA. Codes of medical ethics:

Traditional foundations and contemporary practice. Social Sci Med.

1986;22:1175-9.

2. van Mook WK, van Luijk SJ, O'Sullivan H, Wass V,

Zwaveling JH, Schuwirth LW, et al. The concepts of professionalism and

professional behaviour: Conflicts in both definition and learning

outcomes. Eur J Intern Med. 2009;20:e85-9.

3. van Mook WN, Gorter SL, De Grave WS, van Lujk SJ,

Wass V, Zwaveling JH, et al. Bad apples spoil the barrel: Addressing

unprofessional behavior. Med Teach. 2010;32:891-8.

4. Papadakis MA, Arnold GK, Blank LL, Holmboe ES,

Lipner RS. Performance during internal medicine residency training and

subse- quent disciplinary action by state licensing boards. Ann Intern

Med. 2008;148:869-76.

5. Regulations on Graduate Medical Education 1997.

Medical Council of India website. Available from:http://www.mciindia.org/Rules-and-Regulation/GME_REGULATIONS.pdf.

Accessed June 22, 2014.

6. Medical Council of India. Post Graduate Medical

Education Regulations 2000. Available from: http://www. mciindia.org/RulesandRegulations/PGMedical

EducationRegulations2000.aspx. Accessed July 8, 2014.

7. Epstein RM, Hundert EM. Defining and assessing

professional competence. JAMA. 2002;287:226-35.

8. O'Sullivan H, Van Mook W, Fewtrell R, Wass V.

Integrating professionalism into the curriculum: AMEE Guide No. 61. Med

Teach. 2012;34:e64-7.

9. Steinert Y, Cruess S, Cruess R, Snell L. Faculty

development for teaching and evaluating professionalism: from programme

design to curriculum change. Med Educ. 2005;39:127-36.

10. Madhok R. The Global Indian Doctor: Workshop on

Promoting Professionalism and Ethics - Brief Notes and Next Steps. 2014

Jan 10; Kolkata, India. Available

from:http://leadershipforhealth.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Event-report.pdf

Accessed September 29, 2014.

11. Hawkins RE, Katsufrakis, Holtman MC, Clauser BE.

Assessment of medical professionalism: Who, what, when, where, how, and

…why? Med Teach. 2009; 31:348-61

12. Cruess SR, Cruess RL. Professionalism must be

taught. BMJ. 1997;315:1674-6.

13. Ponnamperuma G, Ker J, Davis M. Medical

professionalism: Teaching, learning, and assessment. South East Asian

Journal of Medical Education. 2007;1:42-8.

14. Wilkinson TJ, Wade Wb, Knock LD. A blueprint to

assess professionalism: Results of a systematic review. Acad Med.

2009;84:551-8.

15. Goldie J. Integrating professionalism teaching

into undergraduate medical education in the UK setting. Med Teach.

2008;30:513-27.

16. Cruess SR, Cruess RL. Teaching professionalism -

Why, what and how? Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2012;4:259-65.

17. Jochemsen-van der Leeuw HG1, van Dijk N, van

Etten-Jamaludin FS, Wieringa-de Waard M. The attributes of the clinical

trainer as a role model: A systematic review. Acad Med. 2013;88:26-34.

18. Cruess R, Cruess S. Teaching professionalism:

General principles. Med Teach. 2006;28:205-8.

19. Passi V, Doug M, Peile E, Thistlethwaite J,

Johnson N. Developing medical professionalism in future doctors: A

systematic review. Int J Med Educ. 2010;1:19-29.

20. Perry M, Maffuli N, Wilson S, Morrissey D. The

effectiveness of art-based interventions in medical education: A

literature review. Med Educ. 2011;45:141-8.

21. Arnold L. Assessing professional behaviour:

Yesterday, today and tomorrow. Acad Med. 2002;77:502-15.

22. Goldie J. Assessment of professionalism:

Consolidation of current thinking. Med Teach. 2013;35:e952-6.

23. Hodges BD, Ginsburg S, Cruess R, Cruess S,

Delport R, Hafferty F, et al. Assessment of professionalism:

Recommendations from the Ottawa 2010 conference. Med Teach.

2011;33:354-63.

24. Norcini J, Burch V. Workplace-based assessment as

an educational tool: AMEE Guide No.31. 2007;29:855-71.

25. Adkoli BV. Assessment of Professionalism and

Ethics. In Principles of Assessment in Medical Education. (Ed: Singh T,

Anshu) Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers. New Delhi. 2012:.p. 180-190.

26. van der Vleuten CPM. The assessment of

professional competence: Developments, research and practical

implications. Adv Health Sci Educ. 1996;1:41-67.

27. Singh T, Modi JN. Workplace-based Assessment: A

step to promote competency based postgraduate training. Indian Pediatr.

2013;50:553-9.

28. Cruess R, McLlroy JH, Cruess S, Ginsburg S,

Steinert Y. The professionalism mini-evaluation exercise: A preliminary

investigation. Acad Med. 2006;81:S74-8.

29. Singh T, Anshu, Modi JN. The Quarter Model: A

proposed approach for in-training assessment of undergraduate students

in Indian medical schools. Indian Pediatr. 2012;49:871-8.