|

India was one of the first

countries to adopt the

World Health Organization’s Expanded Programme

of Immunization (EPI). The program started

globally in 1974 and was initiated in India in 1978. Since its

inception, considerable progress has been made in terms of reduction in

disease burden. Despite these achievements and tremendous advances in

economic and technological spheres in recent years, the burden of

vaccine-preventable diseases remains unacceptably high, in comparison to

developed countries and also many developing countries [1]. One of the

obvious reasons for this could be that the level of coverage with

individual vaccines does not meet the target of sustained high coverage

required to control/eradicate disease. However vaccination coverage data

released by official sources such as the Ministry of Health and Family

Welfare [2] and Indian Council of Medical Research [3], consistently

suggested acceptably high levels of vaccine coverage in India. In

contrast, independent sources such as joint WHO-UNICEF (United Nations

Children’s Fund) report revealed 20-30% differences from the official

data for each vaccine in the national program. More recently, the

National Family Health Survey (NFHS) series [4-6] have shown that the

true vaccination coverage (estimated by robust methodological

procedures) is actually even lower than formerly believed. Over and

above this, the tendency to present vaccination performance in terms of

average coverage rates raises yet another problem viz. the issue

of equity. Averages often mask the wide disparity between extremes; in

the case of childhood vaccination in India, this is especially true as

the range for all observations is extremely high. As an example, the

latest NFHS report [6] gives the national average for complete

vaccination as 43.5%; however this masks the fact that performance in

states like Tamil Nadu with 81% coverage is vastly different from states

like Nagaland with 21% coverage.

Pande and Yazbeck [7] demonstrated the importance of

looking beyond national average figures for childhood vaccination to

uncover disparities masked by the average. They described significant

heterogeneity between states and highlighted the north-south imbalance.

They used the term ‘total system failure’, to describe uniformly low

vaccination coverage across all population segments in some states. They

recognized that some states could have high overall vaccination

performance but significant inequities; in contrast there could be

states with low performance but greater equity.

Gaudin and Yazbeck [8] also reiterated that average

values do not reflect the true picture or provide information for

action; they were concerned about the relationship between "efficiency"

and "equity". The former term is a euphemism for performance, in other

words the overall vaccination coverage; whereas the latter describes the

distribution of vaccination across different groups. Their analysis of

NFHS-2 data [5] revealed areas that had more equitable distribution of

vaccination coverage, but very low overall coverage (high equity but low

efficiency). Enhancing efficiency (coverage) in such areas might

increase inequities. They therefore advocated using Wagstaff’s extended

achievement index (comprising inequality-adjusted immunization scores)

rather than vaccination coverage alone, to allow examination of both

efficiency and equity.

Equity in immunization should not be restricted to

merely creating equal opportunities for immunization of children within

the country (in a sense this already exists as vaccination is provided

free-of-cost to all infants all over the country through a vast network

of public sector institutions). It is also concerned with identifying

the groups at highest risk of remaining unvaccinated and bridging

gaps/imbalances as far as possible. In this regard, the NFHS surveys

[4-6] have provided a vast body of data on the immunization status of

infants grouped by various individual, family, and social

characteristics. The need of the hour is to systematically examine all

sources of data reflecting inequities in vaccination. Such an exercise

would be beneficial in identifying the groups of infants at highest risk

of remaining unvaccinated; and also the characteristics of infants with

high as well as low vaccination coverage status. However no such

document is currently available.

This systematic review of literature was undertaken

to identify inequity in childhood routine immunization in India; and to

explore the reasons for the same.

Methods

Study design: This was a descriptive systematic

review of literature pertaining to childhood vaccination with specific

emphasis on examining and exploring the issues of equity and inequity in

childhood immunization. No secondary data analysis (meta-analysis or

other statistical tests) was undertaken. The design corresponded to

previously used Methodology for this kind of research question [9].

Inclusion criteria

Types of publications: This was a broad-based

review and included all types of publications (available in the public

domain) reporting childhood vaccination in India by direct data

collection through surveys, interviews, research trials, etc or

secondary analysis of published data obtained through one or more of

these methods. Publications representing estimations, data

extrapolations, or employing other indirect methods to calculate

childhood vaccination such as consumption of vaccine doses,

administrative databases, financial logs, etc were not included. No

restriction was applied in terms of type of study, methodology employed,

type of data analysis, or peer-review of publications. Where multiple

sets of data were available through serial updates, the most current

publication was included.

Types of participants: Publications were included

if they contained data on childhood vaccination. The definition of

child/childhood was age group less than five years.

Vaccination/immunization pertained to vaccines in the National

Immunization Schedule, viz. BCG at birth, three doses of DPT and

OPV at 6, 10 and 14 weeks; one dose of measles vaccine at 9 months of

age; and booster doses at 18 months and 5 years. The National

Immunization Schedule also includes a booster dose of tetanus toxoid

(TT) at 10 years of age and 2 doses tetanus toxoid vaccination of

pregnant women. However publications describing these were not included

as they do not directly pertain to the focus of this review. Similarly,

publications on vaccines that are currently not in the National Schedule

(such as hepatitis B, MMR, and newer vaccines) were not included.

Types of outcome measures: The primary outcome

measure was ‘complete vaccination/immunization’ defined as per the 1998

World Health Organization (WHO) guideline viz. receipt of one

dose of BCG vaccine, three doses of DPT and OPV vaccines, and one dose

of measles vaccine by infants in the age group 12-23 completed months.

Secondary outcome measures were (i) ‘no vaccination/immunization’

defined as failure of an infant 12-23 months old to receive even a

single dose of the vaccines listed above, and (ii)

‘partial/incomplete vaccination/immunization’ defined as receipt of

vaccine doses between ‘no vaccination’ and ‘complete vaccination’.

Search methods for identification of studies: The

following databases were searched: Medline through Pubmed

(www.pubmed.com) on 27 November 2011 and updated during 6-12 December

2011. Websites of the World Health Organization, United Nations

Children’s Fund (UNICEF), Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) series,

and Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, were searched between 12 and

27 December 2011. In addition, reference lists of included publications

were searched to discover additional data. No attempt was made to obtain

unpublished data, or data unavailable in the public domain, or data

available within specific institutions at the national, state or local

level. Publications were selected for potential inclusion by screening

titles (first step), screening abstracts of relevant titles (second

step) and studying the full text of relevant abstracts (third step). At

this stage, decision to include or exclude a publication was made.

Search strategy: A Pubmed MeSH search for the

term "equity" returned two categories viz. "Tax Equity and Fiscal

Responsibility Act" (1985), and "The remuneration paid or benefits

granted to an employee" (1978). As neither of these terms was relevant

to this systematic review, additional MeSH search for the term

"Disparity" was undertaken; this returned three categories viz..

"Vision Disparity" (1989), "Healthcare Disparities" (2008) and "Health

Status Disparities" (2008). The last term "Health Status Disparities"

was relevant and hence explored further, yielding 13 subheadings;

amongst these, the following were considered relevant: "statistics and

numerical data, trends, utilization". Therefore the following search

string was used to include citations related to disparity:

"(("Healthcare Disparities/statistics and numerical data"[Mesh]) OR

"Healthcare Disparities/trends"[Mesh]) OR "Healthcare

Disparities/utilization"[Mesh]". This was combined with terms for

immunization/vaccination and India; using the search string: "(immuniz*

OR vaccin*) AND India*". An additional search for the specific terms

‘equity’ and ‘inequity’, combined with vaccination/immunization in India

was undertaken using the string "(vaccin* OR immuniz*) AND India* AND (equit*

OR inequit*)". Following this, a series of searches was undertaken using

specific terms for gender, wealth/poverty, area of residence, social and

socio-economic factors. The detailed search strings for these searches

are listed in Table I.

Table 1 Outline of the Terms, Strings, Strategy and Output for Search and Step-wise

Decision to Include/exclude publication

|

Search for: |

Search string |

Search strategy |

Titles |

Abstracts

|

Full-text |

Included |

Disparity in vaccination

|

“((immuniz* OR vaccin*) AND India*) AND

(“Healthcare Disparities/statistics and numerical data”[Mesh] OR

“Healthcare Disparities/trends” [Mesh]) OR “Healthcare

Disparities/utilization” [Mesh] |

Web Appendix 1

|

25 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Equity/inequity in vaccination |

(vaccin* OR immuniz*) AND India* AND (equit*

OR inequit*)] |

Web Appendix 2

|

22 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

|

Gender |

(immuniz* OR vaccin*) AND India* AND

gender |

Web Appendix 3 |

47 |

27 |

14 |

9 |

|

Area of residence |

(vaccin* OR immuniz*) AND India* AND

(rural OR urban OR slum) |

Web Appendix 4 |

615 |

76 |

29 |

14 |

|

Wealth OR poverty |

(immuniz* OR vaccin*) AND India* AND

(Wealth OR poverty) |

Web Appendix 5 |

150 |

41 |

18 |

7 |

|

Social factors |

(immuniz* OR vaccin*) AND India* AND

(social OR socio*) |

Web Appendix 6 |

496 |

71 |

31 |

8 |

|

Education or literacy |

(immuniz* OR vaccin*) AND India* AND

(education* or literacy) |

Web Appendix 7 |

582 |

96 |

38 |

9 |

|

Incentives |

(immuniz* OR vaccine*) AND incentive AND

India* |

Web Appendix 8 |

42 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

Results

The output of the multiple Medline searches, and the

step-wise screening for inclusion of publications, is summarized in

Table I. Website searches yielded the three NFHS reports

[4-6] and four additional reports from different Departments of the

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare [10-13]. Searching of multiple WHO

[14,15] and UNICEF [16-19] websites did not yield any additional

publications that could be included. Searching reference lists of

included publications yielded one additional publication.

There were a limited number of publications reporting

nation-wide data; these were the three Demographic Health Surveys [4-6],

a survey conducted by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) [3]

at the invitation of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare in 1999;

and three reports from the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare

[10-12]. Recently the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare and UNICEF,

jointly published the results of a Coverage Evaluation Survey undertaken

during November 2009 to January 2010 [13]; this represents the most

current nationwide data available. This survey evaluated the vaccination

status of 12-23 month old infants drawn from rural (n=12635) and

urban (n=9969) areas. The methodology used was fairly similar to

the NFHS surveys.

Some common trends were noted in the NFHS-3 report

[6] and other documents. The coverage for individual vaccines was much

higher than the proportion of "fully vaccinated" infants; suggesting

significant decline in coverage for each subsequent dose of DPT /OPV and

between the third dose of DPT/OPV and measles vaccine; suggesting that

coverage rates declined as infants grew older. Another interesting

observation is that although DPT and OPV doses are administered at the

same age (and therefore ideally at the same vaccination session), there

was a consistent difference between the coverage for the two vaccines.

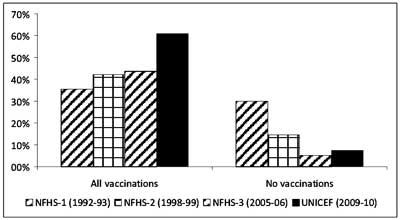

Another important observation from the three NFHS

series [4-6] is the trend over time. In the NFHS-1 survey (1992-93), a

total of 35.4% infants were fully vaccinated and about 30.0% had not

received any vaccination. The second survey (NFHS-2, 1998-99) reported

that 42.0% infants were fully vaccinated and 14.4% had not received any

vaccination. NFHS-3 reported 43.5% full vaccination and 5.1% infants

with no vaccination. These data show that although there was no

significant recent progress in complete vaccination of infants, many

infants are partially immunized. When the data from the UNICEF 2009-10

survey [13] are considered, there appears to be dramatic progress in

vaccination coverage; the complete vaccination rate was 61.0%.

Figure 1 summarizes the data. Further consideration of

time-trends and overall vaccination are outside the scope of this

review. The following sections discusses major factors responsible for

inequities in childhood vaccination.

|

|

Fig 1 Vaccination trend over time (Data

from the three NFHS series and latest UNICEF coverage evaluation

survey ).

|

State-level differences

NFHS-3 data [6] showed that nine states had full

vaccination rate lower than the national average; these include Madhya

Pradesh, Jharkhand, Meghalaya, Bihar, Assam, Arunachal Pradesh,

Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Nagaland. The below-average coverage states

include highly populous states such as Uttar Pradesh.

A group of Indian researchers [62] analyzed NFHS-3

data further to calculate state-wise disparities by gender and area of

residence, for 4 indicators of child health viz. complete

vaccination, prevalence of underweight children, prevalence of diarrhea

and under-five child mortality. To evaluate the effect of wealth, the

authors plotted the concentration curve (CC) and calculated the

concentration index (CI). The former plots the cumulative population

shares of a particular characteristic against the cumulative outcome

(wealth quintiles from lowest to highest) on the x-axis and

cumulative complete vaccination on the y-axis. If the resulting

curve is not a straight line, it indicates inequity in the health-care

outcome (here complete vaccination). The concentration index is

calculated as twice the area between the diagonal (representing zero

inequity) and the actual curve plotted. The larger the value of the CI,

the greater the degree of inequality. They reported that states with the

highest concentration index (indicating greatest wealth-based

inequities) were Bihar, Assam, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Jharkhand and

Uttar Pradesh. Only 8 of 18 states had a coverage rate greater than 50%.

The authors also plotted concentration indices for other health-care

measurements including under-five mortality, prevalence of underweight

and prevalence of diarrhea; the results indicated the same finding.

Analysis by area of residence showed that rural

children were the least likely to have complete vaccination. This

inequity was high in states like Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan,

Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand and Uttar Pradesh. Interestingly, the highest

inequity between rural and urban areas existed in Kerala, followed by

Chhattisgarh and Haryana. A similar analysis by gender was also

undertaken, which suggested the worst imbalance existed in Bihar and

Punjab, followed by Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh.

The ICMR survey [3] conduced across 90 districts in

India during 1999 reported 13 states with complete vaccination coverage

higher than the national average of 63.3%. Only BIMARU (Bihar, Madhya

Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh) and north-east states had coverage

lower than the national average. For some reason, the north-east states

were not named individually; likewise a group loosely labelled "Union

territories and others" were reported to have 82% complete vaccination

coverage. These data showed inexplicably higher vaccination coverage

than the NFHS-2 data for the same time period.

Another nation-wide survey conducted by the Health

Ministry among 4320 infants (distributed equally among rural and urban

areas) [11] reported that 56.6% infants were fully vaccinated, compared

to 50% the preceding year. Nearly one-fifth infants had not received any

vaccination. Among the 18 surveyed states reported, over 85% complete

vaccination was noted in only three states viz. Tamil Nadu

(91.5%), Kerala (91.3%) and Maharashtra (84.7%). Six states (West

Bengal, Punjab, Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka, Delhi and Andhra Pradesh)

reported 70-85% complete vaccination. However, complete vaccination by

the age of 12 months was over 80% only in Kerala and Maharashtra. The

states with lowest vaccination coverage included Bihar (12.8% complete

and 58.0% unvaccinated), Rajasthan (19.7% complete and 38.2%

unvaccinated), Uttar Pradesh (26.7% complete and 45.4% unvaccinated),

and Jharkhand (25.7% complete and 39.3% unvaccinated). It must be noted

that no data on north-east states were presented.

The 2009-10 UNICEF survey [13] reported that 16 of 29

states had complete vaccination rate higher than the national average of

61.0%; the Union Territories combined together had 71.3% complete

vaccination. Four states had greater than 80% complete vaccination;

these were Goa (87.9%), Sikkim (85.3%) Punjab (83.6%), and Kerala

(81.5%). The lowest rate was noted in Arunachal Pradesh (24.8%) and

Nagaland (27.8%). Barring these two states, all the other states had

full vaccination rates above 40%. Even the traditionally poor-performing

states showed dramatically improved performance; complete vaccination

rates in Bihar (49.0%), Madhya Pradesh (42.9%), Rajasthan (53.8%) and

Uttar Pradesh (40.9%) were much higher compared to previous surveys a

few years prior [11,12].

In a document titled, ‘National Health profile 2005’

[10], the Central Bureau of Health Intelligence (CBHI), Directorate of

Health Services of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, published

data on vaccination coverage during the period 1998-99. The document

reported complete vaccination among 42.0% and no vaccination in 14.4%

infants. Although the methodology of obtaining vaccination data was not

clearly described, state-wise coverage for the same period was reported.

The disparity in complete vaccination ranged from 11.0% in Bihar to

83.4% in Himachal Pradesh. No clear regional pattern could be discerned

from the data. For example, among the north-east states, Assam (complete

vaccination 17.0% and no vaccination 33.2%), Nagaland (complete

vaccination 14.10% and no vaccination 32.7%), and Meghalaya (complete

vaccination 14.3% and no vaccination 42.3%) appear to be very different

from Mizoram (complete vaccination 59.6% and no vaccination 10.5%) or

Arunachal Pradesh (complete vaccination 20.5% and no vaccination 28.7%).

The best state performance was reported from Goa (complete vaccination

82.6% and no vaccination 0.0%) and Himachal Pradesh (complete

vaccination 83.4% and no vaccination 2.8%). Maharashtra and Kerala had

very low rates of non-vaccination (2.0% and 2.2% respectively); although

complete vaccination rate was short of 80% in both states. No coverage

data were reported for 6 Union Territories.

A survey independent of the NFHS [20] compared the

vaccination status of infants (12-32 months) in four BIMARU states of

north India (Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh) with

the status in India as a whole. A cluster-survey was undertaken in 30

districts comprising 900 villages (6300 children). Complete vaccination

rate was only 48% compared to 63% for India; and these 4 states

accounted for 70% of India’s unvaccinated children although they have

only 40% of the total population. As in other studies, vaccination rates

were lower among infants with illiterate mothers and residing in rural

areas. The proportion of completely unvaccinated infants was highest in

Bihar (28%). The overall proportion of unvaccinated children in the four

states (22%) was twice the national average. The imbalances between boys

vs girls, rural vs urban, scheduled caste/tribe vs

others, and illiterate vs literate parents; for complete

vaccination coverage as well as unvaccinated infants was similar in the

BIMARU states as all over India.

De also re-examined NFHS-2 data to determine the

factors affecting childhood vaccination in Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, Uttar

Pradesh and Rajasthan [21] where the demographic, health and social

indicators (infant mortality rate, total fertility rate, female

literacy, women employment, maternal prenatal care, and institutional

deliveries) are worse than the national average. He evaluated

vaccination coverage in terms of receipt of three doses of DPT and OPV.

Complete vaccination of infants (rural and urban) in these states was

worse than the national average. The inequities in these four states

were similar to those for the national situation; however in Madhya

Pradesh, there was somewhat better vaccination coverage among Muslims

than other social groups.

A group of international researchers [22] tried to

identify the factors influencing the disparity in childhood vaccination

in two Indian states viz.. Maharashtra and Bihar. These were

selected as they were similar in population size, but diverse in terms

of development, economic status, health indicators (such as infant

mortality and life expectancy), and administrative systems. The

investigators evaluated the vaccination status of over 3000 children in

the age group 1-3 years old. They reported that almost two-thirds of

children in Maharashtra were fully vaccinated; whereas this only about

10% in Bihar. The authors attributed these differences to more educated

parents in Maharashtra, higher use of prenatal services, better media

exposure and higher standard of living. Interestingly, this study showed

that the probability of complete vaccination was higher for children in

rural areas of Maharashtra than urban areas, and attributed this to

better rural health care services in the state.

Mohanty, et al. [23] compared childhood

vaccination by household economic status in Uttar Pradesh with

Maharashtra. Using NFHS data, they observed wide variation in complete

vaccination between Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh. However, the rich to

poor gap estimated by calculation of the concentration index increased

over time in both states suggesting that even in better-performing

states such as Maharashtra, there was significant inequity based on

economic status.

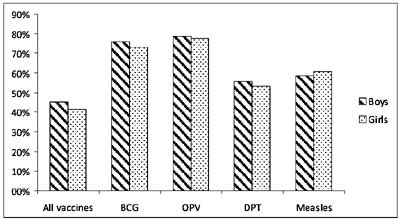

Effect of Gender

There was a higher proportion of boys (53%) than

girls surveyed in NFHS-3 [6]. The complete vaccination rate was 45.3%

for boys and 41.5% for girls. This gender imbalance existed irrespective

of the method of determination of vaccination status; among those whose

vaccination card was examined, 38.8% boys and 36.1% girls were fully

vaccinated. There were 4.3% boys compared to 6.0% girls who had not

received any vaccination. The gap between the genders was about 5% for

most of the individual vaccines including BCG, DPT (all three doses) and

measles; however the gap between boys and girls was considerably less

for the three doses of OPV (about 2%). Fig. 2 depicts a

summary of the NFHS-3 data for different vaccines.

|

|

Fig 2 Gender-based inequity in

childhood vaccination (data from NFHS-3 survey).

|

A group of researchers evaluated gender differences

by examining data from the three NFHS surveys as well as other studies

[24]. They pooled the data and calculated a relative probability of

vaccination among girls of 0.93 (95% CI 0.90-0.98), suggesting a 7%

lower likelihood. Analysis of the serial NFHS survey data suggested that

the overall gender inequity did not increase over time. Six states with

vaccination coverage higher than the national average, were among the 8

states with the lowest proportion of vaccinated girls. While the overall

girl to boy vaccination coverage ratio was 0.95 for India as a whole; it

varied from 0.86-0.90 in Punjab, Haryana and Bihar. In Uttar Pradesh and

Delhi, the ratio was 0.92 and 0.93 respectively. Among the northern

states, Himachal Pradesh and Rajasthan had the most favorable girl to

boy ratio. In the south, the best gender ratio was observed in Tamil

Nadu and Kerala. In the North-east, Jharkhand and Assam had the most

favourable coverage for girls; although the total coverage was very low.

The 2009-10 UNICEF survey [13] reported complete

vaccination in 61.9% boys and 59.9% girls; the unvaccinated infants were

7.9% and 7.2% respectively. The UNICEF (2005) survey across 22 states

(including combined data for 7 north-east states) reported complete

vaccination among 53.9% female infants compared to 55.1% males [12];

however no tests for statistical significance were performed. The

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare coverage evaluation survey during

2001-02 [11] reported fully vaccinated boys and girls as 58.0% and 55.1%

respectively; however no statistical analysis was undertaken. The ICMR

survey (1999) [3] reported 64.2% and 62.2% complete vaccination among

boys and girls respectively; and no vaccination among 9.1% and 10.3%

boys and girls respectively.

Vaccination data of 1279 infants in the age range 1-3

years in West Bengal state was examined from the District Level

Household Survey under the Reproductive and Child Health project

(2002-2004) [25]. It showed 54% complete vaccination rate. Although

there was wide variation in vaccination rates across 18 districts (range

23.3% to 72.2%); full vaccination was 53.0% among boys and 54.7% among

girls; odds ratio 1.061 (95% CI not given).

A research study undertaken in 3 of 6 districts in

Assam state in 2003 [26] evaluated vaccination status of infants based

on examination of vaccination cards and maternal recall. Standard

30-cluster sampling method was used to collect data for 616 infants

between 1-2 years of age. Complete vaccination was higher among male

infants (64.6%) compared to females (59.3%). An econometric analysis of

vaccination data obtained from a sample of over 4333 rural children

between 1-2 years old reported 50% fully vaccinated girls compared to

55% fully vaccinated boys [27]. A survey evaluating measles incidence

and vaccination coverage in urban slums in Ahmedabad during the year

2000 [28] included over 3000 eligible children using standard 30-cluster

sampling. It reported total measles vaccine coverage of 60% but did not

find gender inequalities. The authors also reported the measles

incidence rate and found no disparity between boys and girls. This

confirmed the absence of gender-based disparity for measles vaccine.

A small study to assess the vaccination status of 1-2

year old infants in Goa [29], included 362 infants using 30-cluster

sampling method. The proportions of boys who were fully vaccinated,

partially vaccinated and unvaccinated were 84.6%, 13.8% and 1.6%

respectively; it was 86.2%, 9.8% and 4.0% for girls. However the author

did not report the absolute number of infants in each group.

A survey carried out in Surat city [30] to calculate

the incidence of measles among children below the age of five years

collected measles vaccination data of 2597 children (9 months to 5

years), using parental recall and examination of immunization cards. The

overall coverage rate in boys was 49.3% compared to 47.2% among girls.

Although the overall difference was not statistically significant;

analysis by age of children revealed gender-based differences among

younger infants. Thus 33.7% boys in the 9-11 month age group were

vaccinated, compared to 26.1% girls; likewise 52.9% boys and 46.2% girls

in the age group 1-2 years were vaccinated. The gap narrowed with

increasing age; 52.3% boys and 49.8% girls in the 2-3 year age group

were vaccinated. Beyond that age, the gender differences narrowed

further and a slightly higher percentage of 4-5 year old girls had been

vaccinated.

Srivastava and Nayak [31] presented a brief report of

gender bias in vaccination coverage in Patna, the capital of Bihar state

during the years 1983-1990. However, the results were presented

graphically and numerical data could not be extracted.

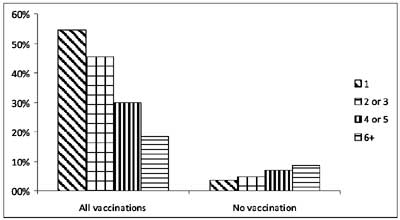

Birth order

The NFHS-3 data [6] showed a trend of declining

vaccination with increasing birth order (Fig. 3). The

proportion of fully vaccinated infants by birth order was 54.6% (first

order), 45.3% (second or third), 29.9% (fourth or fifth) and 18.5%

(sixth or higher). The proportion of unvaccinated infants also showed a

direct relationship; 3.7% among first order, 4.7% among second/third

order, 7.0% among fourth/fifth, and 8.6% among sixth/higher order. Since

the NFHS-3 data presented combined data for birth orders 2 and 3; and 4

and 5; information on each of these could not be obtained separately.

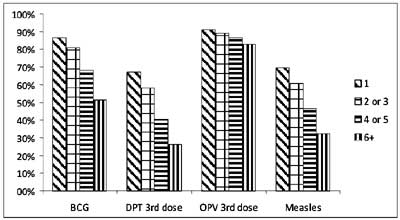

There was also no statistical analysis to confirm the risk associated

with higher birth order. Analysis of coverage for individual vaccines (Fig.

4) highlights two points: the coverage for OPV is higher than for

DPT as observed previously; and the gaps between increasing birth orders

is much lower for OPV compared to all the other vaccines.

|

|

Fig 3 Relationship of birth order and childhood

vaccination (data from NFHS-3 survey).

|

|

|

Fig 4 Coverage of individual vaccines

and relationship to birth order (data from NFHS-3 survey).

|

The 2009 Coverage evaluation survey [13] reported

complete vaccination among infants with birth order 1, 2, 3, 4+ as

67.4%, 64.7%, 53.7%, and 40.4% respectively. The proportion of

unvaccinated infants was 4.4%, 6.7%, 10.8%, and 16.0% respectively.

Analysis of the three NFHS surveys [24] showed that

although higher birth order infants had lower vaccination coverage,

girls were particularly disadvantaged. Among third birth order infants

with two older sisters, only 36.1% girls received age-appropriate

vaccination compared to 45.0% boys. However, third birth order girls

with two older brothers had slightly higher rates than boys in the same

situation.

In a survey of vaccination status of children

dwelling in urban slums in Agra city [32], nearly two-thirds of

unvaccinated infants had birth orders two or greater. Interestingly,

among 228 fully vaccinated infants also, nearly half had birth order two

or higher. The unadjusted and adjusted (for gender and age of child)

relative probability of complete vaccination was significantly lower for

second and third birth order infants compared to first birth order

infants; 0.52 (95% CI 0.36-0.76) and 0.67 (95% CI 0.40-1.13)

respectively.

A small-scale survey in Goa [29], also reported lower

proportion of fully vaccinated infants with higher birth order; it was

86.6%, 88.8%, 69.2% and 75.0%; for birth orders 1, 2, 3 and 4

respectively. The respective proportion of unvaccinated infants was

1.1%, 2.0%, 7.6% and 25.0%. The author did not report absolute numbers

of children in each group.

Pande [33] studied the effect of the gender of older

siblings on the gender-imbalance in rural areas. She reviewed NFHS-1

data and reported that first birth order boys had 38% complete

vaccination compared to 36% in first birth order girls. The complete

vaccination rate of infants with one older sister was 35% among boys and

31% among girls; the rates were identical for boys and girls with two

older sisters. For boys with one older brother, the rate was 35%; the

corresponding rate for girls was 32%. Interestingly, infants with two

older brothers had significantly lower vaccination rates; 22% for boys

and 26% for girls.

Residential Area (Urban, Rural and Urban Slum)

The NFHS-3 survey [6] reported that 57.6% of urban

infants were fully vaccinated compared to 38.6% in rural areas. The

percentage of infants who were not vaccinated was 5.7% in rural areas

compared to 3.3% in urban areas. The urban-rural gap existed for all

individual vaccines, although the gap was lowest with the 3 doses of

OPV. No statistical analysis was carried out in the NFHS-3 report.

The UNICEF 2009-10 survey [13] recorded complete

vaccination in 58.5% rural infants compared to 67.4% urban infants; the

respective unvaccinated infants were 8.5% and 5.2%. The ICMR (1999)

survey [3] evaluating vaccination status of 19000 infants across India

also reported a rural-urban imbalance in complete vaccination (urban

71.7% vs rural 58.5%) as well as no vaccination (rural 11.9%

vs urban 5.7%).

A secondary analysis of NFHS-3 data [34] showed that

among infants residing in urban areas, there were statistically

significant differences in vaccination coverage (BCG, first dose of DPT,

third dose of DPT, and measles) by gender, maternal education level,

maternal occupation, (not working vs working), partner’s

occupation (unemployed/labour vs salaried/professional),

regularity of occupation (all-year vs seasonal/occasional), caste

and religion. Binary logistic regression analysis to calculate the

independent effect of these variables (the dependent variable was "ever

had vaccination") showed a statistically significant effect of maternal

education; no education or incomplete primary education OR 0.238 (95% CI

0.079-0.718); primary education OR 0.304 (95% CI 0.097-0.954). However,

middle/incomplete secondary education showed OR 0.969 (95% CI

0.311-2.968). The other statistically significant effect was found for

‘mother’s autonomy’ (defined as "mother has no money for own use"); OR

0.627 (95% CI 0.408-0.962). There was no statistically significant

independent effect of infant’s gender, wealth category, caste, religion,

maternal occupation, partner’s occupation, or regularity of employment.

The UNICEF nation-wide survey (2005) [12] sampled 30

rural and 15 urban clusters across 22 states (the 7 north-east states

were clubbed together) and reported complete vaccination rate of 47.4%

in rural areas compared to 67.8% in urban areas. The respective

proportion of unvaccinated infants was 18.4% and 7.9%. In terms of

timeliness, only 39.3% infants were completely vaccinated before the

first birthday.

The Department of Family Welfare survey (2002) [11]

reported complete vaccination among 50.3% infants in rural areas

compared to 74.4% in urban. The respective data for non-vaccinated

infants was 23.7% and 8.9% (national average 19.8%).

A small survey in Kerala [35] compared vaccination

rates in three areas; urban, semi-urban and rural. The literacy rate in

all the three areas was above 90%. Standard 30-cluster sampling of

infants 12-23 months old was done and vaccination cards were examined.

The complete vaccination rates in the urban, semi-urban and rural area

were 77.5%, 76.7% and 77.3% respectively. The respective proportions of

unvaccinated infants were 4.2%, 1.9% and below 1%. Although coverage

rates of BCG and DPT/OPV were close to 90% or higher in the three areas,

measles vaccination was highest in the semi-urban area (90.6%) compared

to 77.9% in urban and 79.0% in rural areas.

In Goa state 80% infants residing in rural areas were

fully vaccinated compared to 90.6% infants living in urban areas [29];

however the author did not define urban and rural in the study.

A survey carried out in Chandigarh Union Territory

used maternal recall to assess vaccination status of infants (12-23

months) attending pulse polio booths on a National Immunization Day

[36]. A sample was drawn from 20 urban booths, 16 booths in slums and 4

rural booths to approximate Chandigarh’s population distribution is 50%

urban, 40% in slums and resettled colonies and 10% in rural areas. The

respective proportion of fully vaccinated infants was 80%, 59%, and 83%;

and proportion of unvaccinated infants was 2%, 27%, and 4%.

Another survey in Chandigarh assessed the vaccination

status of 12-23 month old infants [37] from 30 clusters (18 urban, 9

slum, and 3 rural) selecting 40 households from each. The population

distribution was 78% in urban areas, 12% in slums and 10% in rural

areas. The proportion of fully vaccinated infants was 30% in slums, 74%

in rural areas and 62.5% in urban areas. As in other surveys, there was

significant drop-out rate between initiation of vaccination with BCG to

third dose of DPT and measles vaccine.

A vaccination coverage survey in West Bengal [25]

documented complete vaccine coverage of 48.9% in rural areas and 63.9%

in urban areas. Low coverage was observed among the vulnerable groups of

poor minorities, especially in rural areas. Another survey in 3

districts of Assam [26] reported complete vaccination among 85.9%

infants in urban areas compared to 58.7% in rural areas.

Nearly two decades back, a survey [38] in New Delhi

evaluated the vaccination status of children in Narela region having

both rural (population 236000) and urban (population 221000) zones.

Thirty clusters were selected and immunization data of 422 infants

(12-23 month old) was recorded. Complete vaccination (defined in this

study as BCG and three doses of DPT and OPV) was 70.0% in rural area and

73.1% in the urban area. Coverage of individual vaccines in the rural

and urban zones was respectively 83.8% and 88.7% for BCG, 75.7% and

78.8% for third dose of DPT; and 34.3% and 39.2% for measles vaccine.

A community based, cross-sectional survey in two

urbanized villages in East Delhi among 2-4 year old children [39]

collected vaccination data by house-to-house visits. In this study

"urbanized village" was defined as those with population greater than

4000, or population density greater than 400 per square kilometre, or

greater than 75% males employed in activities other than agriculture.

Incidentally, both the selected areas had Health Centers where weekly

vaccination sessions were held. Immunization cards were examined to

ascertain the vaccination status; if unavailable, maternal recall was

used. Among 693 children, the survey did not find any differences in

complete vaccination rates between children living in nuclear or joint

families; or skilled or unskilled paternal occupation. An interesting

finding was that while only 34.6% infants delivered at home were fully

vaccinated; 58.2% of those born in hospitals had received complete

vaccination; the odds ratio was 2.64 (95% CI 1.86 to 3.75). The survey

also reported that 68.2% infants with immunization cards were fully

vaccinated compared to only 27.7% children who did not have cards; odds

ratio 5.78; 95% CI 4.05 to 8.25.

A study examined the vaccination status of 746

children (<2 years old) among migrant families in Delhi through a

30-cluster cross-sectional survey [40] in 23 slums and 7 resettlement

colonies. They further classified the families as either ‘recent

migrants’ (migrated to Delhi within the preceding 5 years) or ‘settled

migrants’ (migrated to Delhi more than 5 years prior). Both groups had

similar demographic profiles in terms of origin, ethnicity, social class

and religion. Vaccination status was determined by examining vaccination

cards and if unavailable, maternal report. The overall vaccination

coverage among migrant families was lower compared to 83.2% among

non-migrant residents of Delhi (although the authors did not measure

this directly). Complete vaccination was recorded in 64.3% recent

migrant infants and 80.8% in settled migrant infants (adjusted OR for

settled migrants 1.93, 95% CI 1.18-3.14). Similarly, coverage with

individual vaccines was lower among recent migrant families;

additionally the difference between settled and recent migrants was

smaller for initial vaccines than those administered later. Thus, 92.6%

recent migrant infants and 89.9% settled migrant infants had received

BCG; whereas 66.2 % and 77.1% of recent and settled migrant infants had

received three doses of DPT. For measles, 67.3% recent migrant infants

were vaccinated compared to 82.0% of settled migrant infants.

Analysis of factors affecting vaccination status

showed better complete vaccination rate with maternal education status

(adjusted OR for >6 years formal education compared to no education was

4.04, 95% CI 2.04-8.00), higher maternal age (adjusted odds ratio for

mothers older than 30 years compared to less than 30 years was 4.47, 95%

CI 1.47-14.15); regular salaried employment of heads of families

(adjusted odds ratio 5.44, 95% CI 1.76-16.77). Another significant

finding was that mothers who had received prenatal care had more

completely immunized infants; adjusted odds ratio for 1-2 antenatal

visits vs no visits was 2.34 (95% CI 1.17-4.67), and for more

than 3 visits 3.89 (95% CI 2.07-7.31). Another finding was a beneficial

effect of postnatal visits by health-care personnel; the odds of

complete vaccination was 2.74 (95% CI 1.42-5.28) compared to no

postnatal visits.

A cross-sectional survey [41] to evaluate missed

immunization opportunities and reasons for non-vaccination in 32 slums

of Udaipur city, included 262 infants (9-24 months old) using 30-cluster

sampling. Vaccination cards and maternal recall were used to determine

vaccination status. The survey recorded 36% complete vaccination; 18%

infants were unvaccinated. The individual vaccine coverage was 79% for

BCG, 80% for first dose of DPT and 50.6% for measles vaccine. However,

the contemporary coverage in urban (non-slum) areas was not described to

make comparisons.

A survey in slums of Lucknow city during 2005 [42]

used 30-cluster sampling with 17 infants (12-23 months old) per cluster.

Immunization cards and maternal reports were used to confirm vaccination

status. Multinomial logistic regression showed that low socioeconomic

status (OR=10.8), Muslim religion (OR=4.3), higher birth order (OR=4.3),

home delivery (OR=3.6) and belonging to a joint family (OR=2.1) were

independent predictors of non-vaccination.

A small cross-sectional survey in Orissa [43]

evaluated vaccination status of 71 infants (<2 years old) among migrant

tribals living in slums of Bhubaneswar city. None of the infants was

completely immunized and 25.3% had not received any vaccine. The overall

coverage for BCG was 59%, first dose DPT 62%, 3 doses DPT 23.6% and

measles vaccine 15%.

A multi-indicator cluster sampling procedure was used

in 1999 to evaluate vaccination coverage of 300 infants in 15 of 299

urban slums in Surat, where about 40% of the population resides in slums

[44]. Vaccination cards (maternal recall if unavailable) were used to

estimate vaccination coverage. The overall complete vaccination rate was

25%. While coverage for three doses of BCG as well as OPV and DPT were

higher among boys, measles vaccine coverage was slightly more among

girls (32.8 % vs 27.8 %).

Effect of Poverty and Wealth (Economic Status)

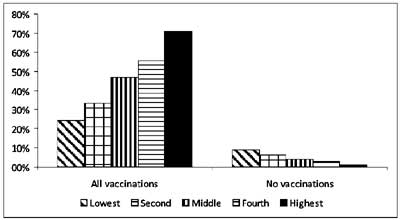

The NFHS-3 survey [6] classified economic status of

families using the ‘wealth index’ defined as a composite score

comprising living standard based on assets (such as television sets,

bicycles etc) and characteristics such as type of construction, access

to water, sanitation system etc. The wealth index was then used to

divide the population into wealth quintiles. The survey report showed

that infants in families with higher wealth indices had better

vaccination status (Fig. 5), although there was no

statistical analysis of the data.

|

|

Fig 5 Vaccination coverage by wealth

quintiles (data from NFHS-3 survey).

|

A re-analysis of the NFHS-3 data [34] reported that

40% infants among the urban poor (viz. lowest wealth index

quartile) were fully vaccinated; this was statistically significantly

lower than the 65.4% fully vaccinated non-poor children (upper three

wealth index quartiles). These differences between the urban poor and

non-poor existed for infants who did not receive the first dose of DPT

(taken to represent children left out of the immunization program), as

well as those who did not receive the third dose of DPT (representing

children who dropped out from the immunization program).

The UNICEF 2009-10 survey [13] also reported a direct

relationship between the economic status of families and vaccination

coverage; the respective complete vaccination rate in the ascending

order of wealth quintiles was 47.3%, 61.8%, 66.4%, 70.0%, and 76.5%. The

unvaccinated infants in the five quintiles were 13.7%, 6.3%, 4.2%, 4.7%,

and 2.7% respectively. This survey also reported complete vaccination

rate among families with and without BPL (below poverty line) cards; it

was 60.22% and 61.4% respectively. The unimmunized infants were 7.2% and

7.9%, respectively.

Gaudin, et al. [8] used concentration ratios

comparing cumulative population characteristics such as wealth with

cumulative vaccination coverage. They then used this method to compare

data from the first (1992-93) and second (1998-99) NFHS surveys to

estimate the changes over time. They reported that in 1999, there were

fewer areas where children did not receive any vaccination (reflecting

total system failure); the decline was from 38% to 18% in rural areas;

and 17% to 6% in urban areas. However, although wealth-based

inequalities decreased in urban areas, it did not change significantly

in rural areas. This suggests that less wealthy people in villages had

lower vaccination rates. In rural areas, although vaccination coverage

increased, much of this occurred in wealthier segments of the

population.

A group of researchers addressed whether improving

trends in immunization coverage over time could actually mask greater

inequities between different segments of population. They re-analysed

NFHS-3 data and calculated an adjusted score against the backdrop of

average health status of the population and wealth strata [63] and

showed that poor child health is mostly concentrated in poor households;

and the highest impact of increasing average immunization coverage rates

occurred in wealthier households. The adjusted score for full

immunization rate actually declined for many of India’s southern states

which are generally at the top end of the immunization rankings. The

data showed inequalities in child health achievement in states with

better health status such as Kerala and Goa; and states with higher

economic status such as Punjab and Haryana. The traditionally poor

performing states such as Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Orissa,

Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh, showed a mixed pattern. Some smaller

states like Jharkhand, Sikkim, Manipur and Arunachal Pradesh showed

evidence of better equity but comparatively lower average. There were

only two states viz. Tamil Nadu and Himachal Pradesh that showed

progress in terms of both equity and achievement.

Mohanty, et al. [23] analysed NFHS data for

trends in childhood vaccination, by household economic status. The

economic status was calculated from consumer durables, land size,

housing quality and water and sanitation facilities of the household.

The concentration index was used to calculate the gap between wealthier

and less wealthy households. The complete vaccination coverage of

infants in the three NFHS surveys was 36%, 40% and 44%. However the

absolute immunization coverage as well as rate of change was much lower

among the lowest wealth quintile; it was 18%, 23% and 24% during the

three surveys. The coverage in the three surveys among second lowest

wealth quintile was 27%, 34% and 33% respectively. In contrast, coverage

for the wealthiest quintile was not only higher than less wealthy

households in each of the surveys, but also showed a rising trend over

time; it increased from 64% (NFHS-1) to 71% (NFHS-3).

The UNICEF 2005 survey used the type of dwelling unit

as an indirect reflection of household economic status [12]. Among

families living in kachcha houses, complete vaccination was noted

in only 40.9%; it was 57.5% in those living in semi-pucca houses

and 65.3% among infants living in pucca houses.

In a study based in Udaipur district of Rajasthan

[45], vaccination status of 2365, under-five children presenting to

primary health centers for curative services, was analysed by household

economic status (determined by the possession of assets and amenities).

In addition to vaccination status, access to piped water was also

assessed. Overall only 40% of 12-23 month old infants were completely

vaccinated; the coverage by ascending order of wealth quartiles was 19%,

29%, 46%, and 68% respectively; the trend existed for all individual

vaccines except OPV. Although there was a direct relationship between

maternal literacy rate and immunization, literacy was itself associated

with socioeconomic status. The literacy rate in the ascending order of

wealth-based quartiles was18%, 42%, 72%, and 92%, showing that women

from wealthier families were more likely to be literate. The survey also

reported a negative relationship between vaccination and distance of the

family from health-care centers; however it was observed that less

wealthy families lived farther away from primary health-care facilities

than more wealthy counterparts. These observations suggest that

household economic status is a significant determinant of childhood

vaccination.

The survey carried out throughout the state of West

Bengal [25] evaluated the impact of living standard; complete

vaccination was 44.6% among those with low standard of living; 58.0% for

medium standard; and 77.1% with high standard of living. In another

study [27] of infants (1-2 years old) residing in rural areas, the

proportion of complete immunization was 45% in poor households and 55%

in non-poor households. In this study, households were classified as

"poor" if the total annual household income was below the poverty line

income.

A survey in Goa [29] categorised household

socio-economic status into 5 unspecified grades; 100% infants in Class I

families were fully immunized; the proportions in other classes were

95.8% in Class II; 92.1% in Class III, 81.7% in Class IV; and 48.6% in

Class V.

Education or Literacy

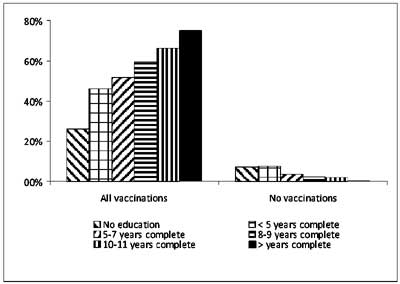

Mother’s education status was assessed in the NFHS-3

survey [6]; there was higher complete vaccination and lower

non-vaccination among infants of mothers with more years of formal

education (Fig. 6). However, no statistical analysis was

done.

|

|

Fig 6 Vaccination coverage by

education/literacy (data from NFHS-3 survey).

|

There was a significant positive correlation between

maternal education and complete vaccination in the UNICEF 2009-10 survey

[13]; 45.3% with no maternal education, 55.4% with <5 years, 64.9% with

5-7 years, 64.9% with 8-9 years, 74.1% with 10-11 years, and 76.6% with

>12 years education. The corresponding unvaccinated infants were 14.3%,

9.0%, 5.1%, 3.8%, 2.1% and 2.0%.

There was a direct relationship between level of

parental education and vaccination status in the UNICEF survey (2005)

[12]. Only 38.2% of illiterate parents were completely vaccinated,

compared to 53.8% with less than 5 years of school education, 59.6% with

5-7 years, 69.9% with 8-10 years, 77.5% with 11-12 years; and 82.4%

among infants whose parents had more than 12 years of schooling.

The Department of Family Welfare survey in 18 states

[11] also reported a positive relationship between complete vaccination

of infants and literacy level of primary care-givers, as follows:

illiterate (31.4%), 1-4 years education (64.4%), 5-8 years (71.3%), 9-14

years (85.5%) and over 15 years (96.7%).

The ICMR 1999 survey [3] reported complete

vaccination rate of 46.4% among infants of illiterate mothers compared

to 64.9% among mothers with primary education, 70.4% with middle

education, and 78.8% with higher secondary maternal education. Paternal

literacy also showed a similar relationship; complete vaccination was

45.8% among infants of illiterate fathers; 59.32% with primary

education, 63.2% with middle education and 69.7% with higher secondary

education. The survey also observed an effect of combined literacy of

both parents; complete vaccination rate was 42.2% infants if both

parents were illiterate, 65.4% if only mother was literate. 50.3% if

only father was literate and 74.4% with both parents literate.

An analysis of over 4000 children living in rural

households in 16 states [27] showed that 66% infants of literate

mothers, 59% of infants with proximate literacy, and 42% infants of

illiterate mothers were fully vaccinated. However, the authors did not

describe definitions for the three categories.

In a cross-sectional study of 693 children (2-4

years) [39] in two urbanized villages in Delhi, 34.4% children of

mothers with no education had received complete vaccination. In

contrast, 48.1% and 50.7% children of mothers who had been educated for

1-8 years and more than 8 years, respectively were fully vaccinated. The

respective odds ratios (compared to no education) were 1.77 (95% CI

1.12-1.28) and 1.96 (95% CI 1.37-2.81). Likewise only 31% of children

whose fathers were uneducated were fully vaccinated compared to 33.7%

and 45.7% where paternal education was 1-8 years and greater than 8

years respectively. The respective ORs were 1.30 (95% CI 0.61-2.1) and

1.80 (05% CI 1.21-2.89). The adjusted OR for complete vaccination was

1.43 (95% CI 1.03-1.99) for literate versus illiterate mothers; and 1.10

(95% CI 0.75-1.60) for literate versus illiterate fathers; suggesting

that maternal literacy was a more important determinant of childhood

vaccination.

A survey in Goa [29] reported that amongst uneducated

mothers, 70.8% infants were fully vaccinated. In contrast, 91.2%, 90.7%

and 100% of infants of mothers with primary, secondary and graduate

level of education respectively had received complete vaccination. The

proportion of fully vaccinated infants showed a gradation with paternal

education; 56% infants of uneducated fathers were fully vaccinated,

compared to 75.3% with primary level, 89.8% with secondary level and

98.5% with graduate level education.

A survey in West Bengal [25] reported complete

vaccination among 61.2% infants with literate mothers and 37.8% with

illiterate mothers; it was 59.9% for infants of literate fathers and

37.6% with illiterate fathers. A survey evaluating vaccination among 616

infants in the age group 1-2 years [26] reported higher complete

vaccination with literate fathers (66.3% compared to 35.4% with

illiterate fathers) and mothers (68.8% compared to 37.9% among

illiterate mothers).

A survey in Agra’s slums [32] reported that over

three quarters of 699 unvaccinated infants had illiterate mothers. Even

among fully vaccinated infants, about 42% mothers were illiterate. The

relative probability of complete vaccination for infants of illiterate

mothers compared to mothers with secondary level education was 0.08 (95%

CI 0.05-0.13) unadjusted and 0.18 (95% CI 0.10-0.30) adjusted for

maternal age and occupation. Among the unvaccinated infants, 92% had

mothers who were not working. This was similar to the proportion in the

fully vaccinated group as well. The relative probability of complete

vaccination among infants of working mothers was 0.37 (95% CI 0.18-0.77)

unadjusted and 0.48 (95% CI 0.21-1.08) adjusted for maternal age, and

education, suggesting that maternal education was a more critical factor

than employment.

A survey in Udaipur district [45] reported complete

vaccination rate of 20% among infants with illiterate mothers, 27% with

less than 5 years education, 42% with 5-7 years education, and 70% among

mothers with more than 8 years education.

One investigator based in the USA postulated an

association not only between childhood vaccination and maternal literacy

at the individual level, but also overall maternal literacy at the

community (district) level [46]. She undertook hierarchical linear

modelling, using the Human Development Profile Index (1994) representing

individual characteristics and the Indian Census (1991) for the

community characteristics; to evaluate within and between social

phenomena. The former provided vaccination data of 5623 infants (1-2

years) and the latter information on literacy rates, wealth, level of

urbanization, etc for 412 districts (rural and urban). Modelling showed

a significant positive relationship between the proportion of literate

females (defined in the Indian census as ability to read and write in

any language) in a district and the likelihood of complete vaccination

of a child. Further modelling controlled for 6 district-level

characteristics representing economic status, access to health-care,

social class, and religion. The positive relationship between district

level of female literacy and complete vaccination of individual children

persisted. The author then undertook modelling after controlling for

literacy status of individual mothers and noted that the positive

relationship between district-level literacy persisted although the

magnitude was somewhat lower. In other words, infants are more likely to

be fully vaccinated if their mothers are literate and they also reside

in an area with overall high female literacy. In the modelling exercise,

the impact of district level female literacy was overcome by higher

educational attainment of individual mothers; suggesting that infants

with highly educated mothers had better vaccination even if the

district-level literacy was not as impressive.

As in other studies, there was a positive

relationship between wealth status and likelihood of complete

vaccination; and significant negative relationship with the proportion

of Muslims and also scheduled tribes in a district. After controlling

for individual factors, modelling suggested that residing in

predominantly Muslim areas increased the likelihood of not getting

completely vaccinated even for non-Muslim infants, those with literate

mothers, and residing in wealthier households. This was in contrast to

caste based disparities; where the effect of residing in an area with

predominantly scheduled tribe households, did not increase the

likelihood of individual non-scheduled tribe children being incompletely

vaccinated. In other words, belonging to scheduled tribe was more

important for incomplete vaccination, than residing in a

disproportionately scheduled tribe area.

Based on these data, the author argued that community

characteristics (especially district-level of female literacy and

wealth) affect childhood vaccination in addition to individual

characteristics.

Effect of Social Factors (Religion, Caste, Women

Empowerment)

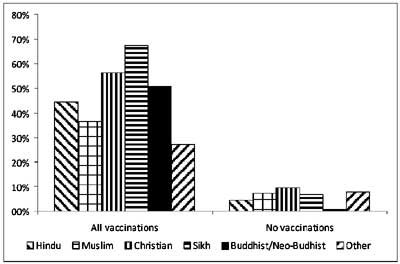

The NFHS-3 survey [6] defined the religion of infants

by that of the head of the family. In general, complete vaccination

coverage was higher among Christians and Sikhs; however the rate of

non-vaccination was also higher among these groups. Muslim households

had lower complete vaccination coverage and higher non-vaccination than

Hindu families (Fig. 7). There was no analysis to confirm

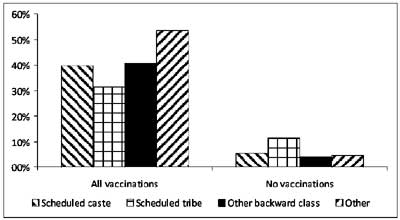

statistical significance. The survey [6] also reported that infants from

general category families had higher vaccination coverage that those

from scheduled caste, scheduled tribe and other backward classes (Fig

8). No statistical analysis as reported.

|

|

Fig 7 Vaccination coverage by religion

(data from NFHS-3 survey).

|

|

|

Fig 8 Vaccination coverage by caste

(data from NFHS-3 survey).

|

UNICEF coverage evaluation survey 2010 [13] reported

58.9% complete vaccination rate among infants from scheduled caste

families, 49.8% among scheduled tribe, 60.6% among other backward caste,

and 66.3% among other castes. The non-vaccination rate was 7.8%, 9.9%,

8.6% and 5.5% respectively. Vaccination rate by religion showed complete

vaccination in 61.2% Hindu infants, 55.7% Muslim infants, 78.2% Sikh

infants, 65.6% Christian infants, and 76.6% infants of other religions.

The previous UNICEF survey (2005) [12] reported

complete vaccination coverage of 52.2% and 53.3% among infants from

scheduled caste and scheduled tribe families respectively; it was 57.6%

among other groups. In rural areas complete vaccination rate among

infants from scheduled caste or tribe families was 46.1% compared to

48.3% amongst other infants. The corresponding data for urban areas was

69.4% among scheduled caste or tribe families; and 67.0% amongst other

families. The survey reported higher rate of complete vaccination

amongst infants from Sikh (81.9%) and Christian (67.3%) households

compared to Hindu (55.4%) and Muslim (45.5%) families.

The Department of Family Welfare survey [11],

reported highest proportion of complete vaccination amongst Sikh

families (71.4%), followed by Christian (65.9%), Jain (61.8%), Hindu

(56.9%) and Muslim (47.2%) infants. The survey also reported 54.0%

complete vaccination among infants in scheduled caste families, 51.7%

among scheduled tribe and 58.1% amongst other families.

In the 1999 ICMR survey across 90 districts [3],

there was a relationship between caste and complete vaccination

(scheduled caste 58.9%, scheduled tribe 48.3% and others 67.2%) as well

as no vaccination (scheduled caste 11.3%, scheduled tribe 16.3% and

others 8.0%). However, there did not appear to be significant inequity

based on religion (proportion of fully vaccinated infants was 63.8%

among Hindus, 61.9% among Muslims, 65.1% among Sikhs, and 59.6% among

Christians).

Another survey [27] of over 4000 children in 16

states showed that 60% infants from Hindu households were fully

vaccinated compared to 40% in Muslim households. A comparison of

households with and without empowered females showed complete

immunization in 61% and 46% infants respectively. The definition of

female empowerment was the opportunity to read newspapers, listen to the

radio, or watch television; for at least 1–2 days per week.

A survey in Goa [29] reported that 83.7% infants in

Hindu households were fully vaccinated whereas 2.4% were unimmunized,

compared to 56.0% and 16.0% in Muslim households.

A vaccination coverage survey in West Bengal [25]

reported 68.2% complete vaccination among Hindu general caste, 47.5%

among Hindu scheduled caste/tribe, and 57.1% among Hindu other backward

class. It was 39.8% among Muslims; and 50.0% among people of other

religions. A 30-cluster vaccine coverage survey covering half of Assam’s

districts [26] reported higher complete vaccination among infants from

Hindu households (62.5%) than Muslim households (55.9%). The authors

also reported lower complete vaccination among families belonging to

scheduled caste, schedule tribe and tea garden caste; as compared to

general caste.

A group of researchers undertook house-to-house

visits in 10 small (population <1000) and large (population 1000-22000)

villages in Vikas Nagar area (population approximately 200000) [47].

Hindu households had higher vaccination coverage than Muslim households,

although the investigators suggested that this was more a result of

higher literacy rate and education than religion alone. Incidentally, no

gender-based inequities were observed.

An intervention trial [48] compared health indicators

in 105 villages in Uttar Pradesh, cluster-randomized to receive either

enhanced awareness through public meetings or no intervention. The

investigators included some data on vaccination status by caste. They

noted that the vaccination rate (defined as receipt of one or more

childhood vaccines) in the control group (that did not receive any

intervention) was comparable (46-47%) among families belonging to

scheduled caste as well as mid to high caste. Although this design is

inappropriate to evaluate the impact of caste; the vaccination rates by

caste were similar in the control group population at baseline as well

as after the one-year trial; whereas it had increased significantly in

the intervention group.

A group of scientists in Tamil Nadu compared

vaccination coverage rates determined by the standard 30-cluster survey

method used by the Government of India and a Purposive method [49]. The

basis for this comparison was the difference in the technique used to

obtain the sample in these methods. Sampling with the 30-cluster method

starts close to the village centre and thereby is likely to exclude the

scheduled caste/tribe and other backward class families living at the

periphery or in pockets. The Purposive method reportedly ensures less

exclusion. Although the data showed no significant coverage differences

with the two methods, 30-cluster sampling method gave slightly higher

coverage rates; there was nearly difference 7% for measles vaccine. The

authors suggested that the conventional 30-cluster sampling method may

yield falsely higher vaccination coverage rates on account of exclusion

of socially deprived segments of the population.

Effect of Access to Health-care Services and other

Infrastructure

The ICMR survey (1999) [3] reported complete

vaccination coverage in only 19% infants living in small (population

<500) villages located more than 5 km away from health centers. In

contrast, villages located within 1 km of a health-care center had 56.9%

coverage. However, some villages that were relatively near health

centers also had lower vaccination.

In a study in Udaipur district in Rajasthan [45],

there was a relationship between the vaccination status of 2365 children

(< 5 years old) and the distance of their household from the nearest

primary health-care centre. Complete vaccination rate was 55% for

households <1 km away, 47% for distances 1-2 km, 32% for distance 2-7

km; and 30% for >7 km from health centers. Incidentally less wealthy

families lived farther away from primary health-care facilities than

more wealthy counterparts.

Almost two decades back, a survey was undertaken in

Lucknow’s slum areas [50]. At that time, there were 110 slums accounting

for about 13% of the city’s population. Among these, 40% slums with

about 47% of the slum population were covered by the Urban Basic

Services (UBS) program launched in 1986. The survey compared the

vaccination status of children living in slums with and without UBS

coverage approximately three years after the program inception. Standard

30-cluster sampling with 7 eligible infants (12-23 months) each was

employed. The proportion of fully vaccinated children was 16.2% in UBS

slums compared to 10.9% in non-UBS slums. The respective

proportions of partially-vaccinated infants were 46.2% and 51.5%. There

was no difference in the proportion of non-vaccinated infants (37.6%

each). The drop-out rate between the first and second doses of DPT

vaccine was comparable in the two types of slums; however the drop-out

rate between the second and third doses of DPT was somewhat higher in

non-UBS slums. The measles vaccine coverage in UBS slums was 18.6%

compared to 11.9% in non-UBS slums.

Another group analyzed vaccination status of 4844,

0-4 year old children and categorised it by their usage of public or

private care sector health-care facilities for outpatient curative

services in the preceding fortnight [51]. They included data for only

one child per household and controlled for multiple factors including

demographics, household socioeconomic status, and state of residence.

The likelihood of vaccination was not different among those who used

private or public sector health-care services except for measles

vaccine. They also categorised the data of those who accessed private

sector services by reasons of proximity or reasons of quality; the

latter had a higher proportion of vaccinated infants.

A group of investigators [52] examined NFHS-1 data

and observed a significantly higher rate of complete vaccination among

infants whose mothers had received antenatal care in the first trimester

compared to those who did not (62.4% vs 31.7%).

A vaccine coverage survey in Assam [26] reported a

positive relationship with access to health-care facilities (64.5%

complete vaccination compared to 57.4% among those with no access). The

data also suggested better vaccination status among those residing

within 2 km of health centers.

A door-to-door household comparative survey was

carried out in 1993 in one rural ICDS (Integrated Child Development

Scheme) block and five non-ICDS rural areas in Madhya Pradesh state

[53]. Vaccination data of 709 and 500 children (1-2 years) respectively

was collected. The proportion of vaccinated infants was lower in the

ICDS areas than non-ICDS areas for all vaccines; 80.2% vs 88.8%

for BCG, 79.5% vs 94.4% for three doses of DPT, 88.0% vs

95.3% for three doses of OPV, and 45.7% vs 62.0% for measles

vaccine. These differences are significant especially as nutritional

status of children in both areas was comparable.

A hospital-based study was conducted in a

tertiary-care teaching hospital in Delhi [54]; wherein the vaccination

status of 325 consecutive admitted children in the age range 1-5 years

was evaluated. Maternal report was the primary method of obtaining

vaccination information; additional examination of vaccination cards was

done where possible. Less than one-fifth children were completely

vaccinated; nearly half were partially vaccinated and one-third had not

received any vaccine. The majority of fully vaccinated children had

vaccination cards that could be cross-checked; whereas cards were

available in only a minority of the other children. Most of the children

who were not fully vaccinated had received multiple doses of OPV during

National Immunization days. The authors presented vaccination data by

gender, religion, parental education, and place of delivery; however as

this was a hospital-based study and the demographic profile of admitted

patients was not described, these variables have not been examined

further in this review.

Sahu et al. [55] examined NFHS-2 data to

estimate the impact of individual and community characteristics such as

age, gender and birth order of infants; maternal age, prenatal care,

post-natal care, parental education, institutional delivery, and access

to basic facilities such as health centers, roads and IEC (information,

education and communication) activities. They conducted a two-step

analysis to evaluate the vaccination status based on different subgroups

and individual as well as community characteristics. The data showed

that infants living in communities with all-weather roads, public-sector

health facilities, and exposed to IEC activities had higher complete

vaccination coverage compared to their counterparts.

Effect of Pulse Polio Immunization Program (PPIP)

A group of investigators studied the effect of the

pulse polio immunization program on routine immunization of infants

(12-35 months) residing in rural areas of Bihar, Madhya Pradesh,

Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh [56]. They evaluated vaccination coverage

before and after the initial years of the pulse polio immunization

program (PPIP) comparing NFHS-1 (1992-93) and NFHS-2 (1998-99) data.

Four outcomes were examined viz.. receipt of first dose of OPV, 3

doses of OPV, at least one dose of any of the non-polio EPI vaccines;

and complete immunization. They reported that the proportion of children

who received the first dose of OPV was 48.1% (95% CI 45.9-50.3%) in 1993

which increased to 72.6% (95% CI 70.6-74.5%) in 1999. Since the coverage

with first dose of DPT during the two periods was not very different;

48.0% (95% CI 45.9%-50.2%) and 49.9% (95% CI 48.0-51.9%) respectively;

the increase in OPV coverage could be attributed to the PPIP. Likewise,

there was no significant change in coverage with at least one dose of

non-polio EPI vaccines; 50.9% (95% CI 48.8-53.1%) and 56.4% (95% CI

54.4-58.4%) in 1993 and 1999 respectively. The complete immunization

coverage in the respective time periods was also similar 17.7% (95% CI

16.2-19.3%) in 1993 and 18.5% (17.2-19.8%) in 1999. Thus there was a

disproportionate increase in OPV coverage between 1992-93 and 1998-99.

The data also showed that although wealth-based inequity declined for

polio vaccination, it increased for other vaccines. Some reduction in

caste- based inequities were observed, but there was no impact on

religion- or residence-based inequities.

The authors offered two possible explanations viz.

that PPIP enhanced knowledge and awareness of polio vaccination but had