Toddlers and even infants, while enjoying their

newfound freedom of movement are frequently at risk of accidental injury

caused by household items. We report a young boy who accidentally

aspirated and was severely asphyxiated by aspiration of a massive amount

of ‘kolam’ (limestone) powder used commonly in Tamilnadu for drawing

floral and other designs on the space leading to their house.

Case report

An 18-month-old male child accidentally tripped and

fell backwards while running carrying a bag containing nearly ½ kg of

kolam powder. The contents of the bag fell heaped on his nose and face,

he became unresponsive and was unable to breathe for a few seconds.

Choking cough, labored noisy respirations, vomiting and cyanosis

followed. He did not develop any seizures. He was brought to the

emergency department of our hospital three hours after the aspiration.

On examination, he was a well nourished child, had

central cyanosis and gasping, irregular respirations. He had severe

supra-sternal and intercostal retractions. There was no stridor. The

chest was hyperinflated and silent bilaterally on auscultation. He was

drowsy but arousable with a Glasgow coma scale of 11/15. His heart rate

was 160 per minute, respiratory rate 36 per minute, and blood pressure

was 82/60 mmHg.

He was intubated and endotracheal suction performed

to remove frothy secretions containing chalky white powder. Stomach wash

was given with saline. He was mechanically ventilated while awaiting

bronchoscopy. Despite high peak inspiratory airway pressures, feeble

breath sounds were heard anteriorly with no breath sounds posteriorly. A

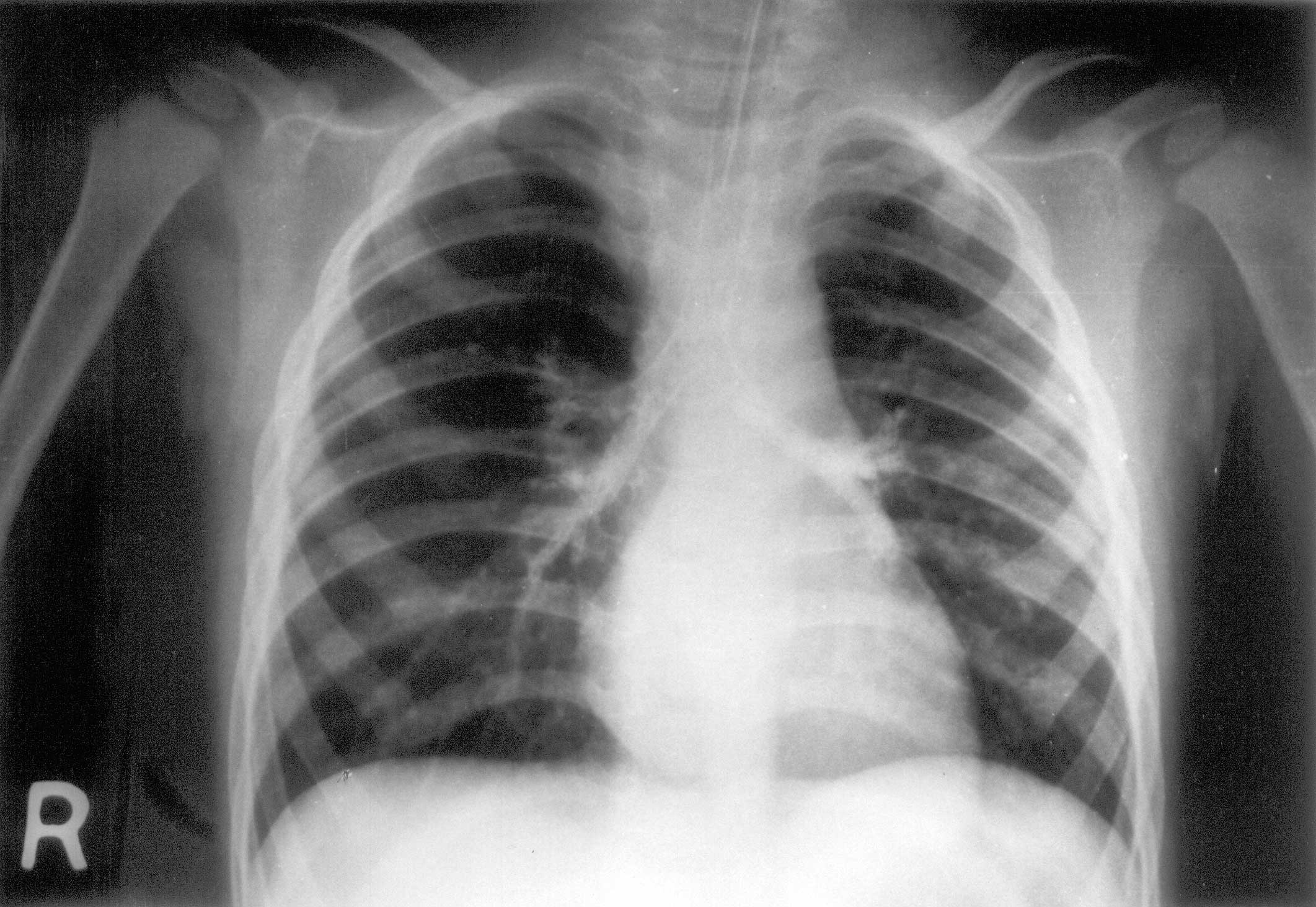

chest X-ray resembled a bronchogram with the trachea and bronchi

being clearly outlined by the calcium content of the inhaled powder (Fig.

1). He was given nebulised terbutaline, intravenous amino-phylline

infusion 0.6 mg/kg/h, 10 mg/kg of hydrocortisone bolus and subsequently

10 mg/kg/day in four divided doses. Parenteral cefotaxime and

metronidazole were also administered.

|

|

Fig. 1. Chest X-ray following powder

aspiration. |

Bronchoscopy done 30 minutes after admission using a

rigid bronchoscope yielded inhaled kolam powder in the trachea and both

major bronchi. There was edema and redness of the bronchial mucosa. The

bulk of the aspirated chalky material was removed by bronchial lavage

with normal saline and suction using a wide bore suction catheter. The

remaining clumps sticking to the bronchial walls were removed with an

extraction forceps. Two mL of adrenaline 1:2,00,000 dilution was

instilled locally in each major bronchus and trachea to reduce post-bronchoscopic

bleeding and reactive bronchospasm.

Following bronchoscopic lavage, the patient was

ventilated mechanically for 15 hours during which period chest physiotherapy

followed by endotracheal suctioning was carried out every 15 minutes.

The air entry in the lower lobes improved signi-ficantly following the

bronchoscopy and later he showed clinical improvement. Serial arterial

blood gas estimation revealed moderate metabolic acidosis that resolved

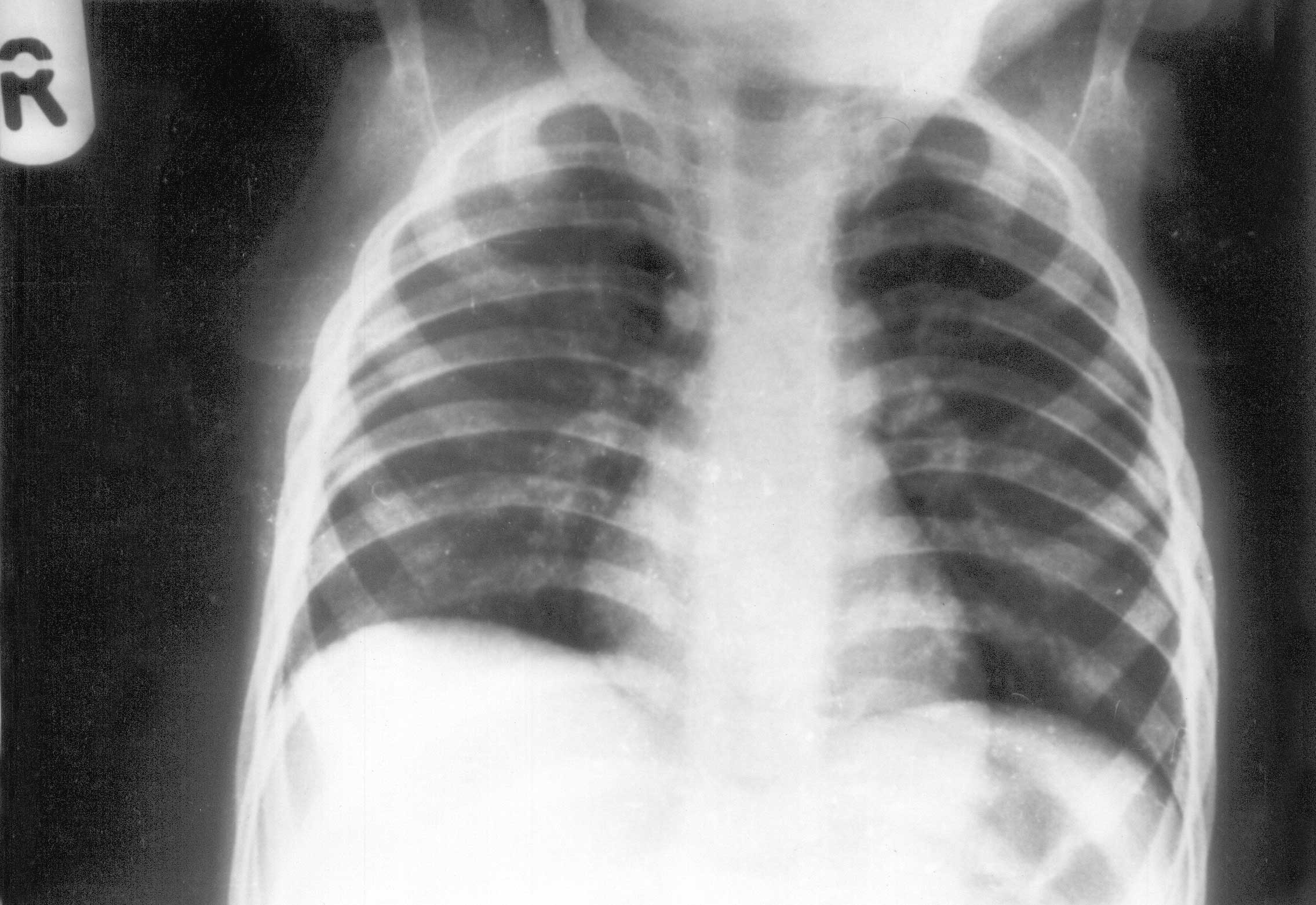

within a few hours of mechanical ventilation. Repeat skiagram six hours

after bronchoscopy showed evidence of bronchiolar obstruction with

perihilar flaring. He was weaned off oxygen over the next 24 hours and

discharged on the fourth day. Biochemical analysis confirmed the

aspirated powder to be calcium carbonate.

At discharge, the child had regular respirations at a

rate of 38 per minute with no chest recession or hyperinflation and

vesicular breath sounds were audible equally. On follow-up at two and

six weeks after discharge, he was asymptomatic with no recurrence of

respiratory distress. The chest radiograph at discharge and at follow-up

(Fig. 2) showed normal lung markings. His serum calcium was 9.4

mg/dL, serum phosphorus was 5.8 mg/dl and serum alkaline phosphatase was

313 U/L at follow up. Ultrasound abdomen showed no evidence of

nephrocalcinosis or urinary tract lithiasis and urinary spot calcium/creatinine

ratio was 0.173.

|

|

Fig. 2. Chest X-ray 3 weeks after discharge. |

Discussion

Accidental aspiration of food objects such as nuts

and seeds are common in young children and may result in death if not

promptly removed. Inedible objects such as balloons(1), coins, pills,

sticks, safety pins, ball bearings, metallic objects, marbles, and baby

powder may also be fatally aspirated.

Though aspiration of ‘kolam’ powder is uncommon,

there are reports of massive talcum powder aspiration from the

West(2-4). Consequences of massive powder aspiration vary from being

asymptomatic to more severe complications such as mild to severe

aspiration pneumonia(2), adult respiratory distress syndrome(5), severe

bronchiolar obstruction, massive bronchitis with pulmonary edema,

atelectasis and compensatory emphysema, acute respiratory

insufficiency/failure needing tracheotomy and mechanical ventilation(4),

progressive diffuse pulmonary fibrosis(3), and increased mortality

(23%). Outcome and prognosis depend on the time interval between the

occurrence of the accident and the hospitalization of the child or

institution of appropriate mode of therapy(4).

Calcium carbonate is insoluble in water, but absorbs

water and tends to form thick flakes on mixing with water(6). This

probably resulted in difficulty in clearing the aspirated material from

the airways in our patient .

An important point to note is that there is usually a

characteristic silent period of several hours between the initial event

of powder aspiration and onset of severe respiratory distress. This

asymptomatic period can lead to wrong parental and medical decisions

resulting in increased morbidity and mortality. The best results in

treatment are obtained by immediate intubation and bronchial wash even

in the absence of respiratory symptoms. Artificial ventilation may be

necessary to overcome very high airway resistance as encountered in our

patient. Corticosteroids and bronchodilators may be helpful(4).

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. Geethanjali A., Department of Clinical

Biochemistry, Christian Medical College Hospital, Vellore, for the

chemical analysis of the aspirated powder.

Contributors: ACP was involved in the care of

this patient and drafted the report, under the supervision of R P. GT

did the bronchoscopy. SGV evaluated serial radiographs and provided the

illustrations.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None stated.