|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2016;53: 627-629 |

|

Rotavirus

Diarrhea in Children Presenting to an Urban Hospital in Western

Uttar Pradesh, India

|

|

Neeraj Teotia, Amit Upadhyay, Sunny Agarwal,

#Amit Garg and *Dheeraj

Shah

From Department of Pediatrics and #Microbiology,

LLRM Medical College, Meerut, UP; and *Department of Pediatrics,

University College of Medical Sciences and GTB Hospital, New Delhi;

India.

Correspondence to: Dr Neeraj Kumar Teotia, Department

of Pediatrics, LLRM Medical College, Meerut, UP, India.

Email: [email protected]

Received: January 02, 2014;

Initial review: January 27, 2014;

Accepted: April 27, 2015

|

Objective: To determine the proportion and clinical profile of

rotavirus-associated diarrhea in children aged 6 months to 5 years.

Methods: Clinical details and stool samples were

collected from 254 children aged between 6 months to 5 years

presenting with acute diarrhea, irrespective of hydration status, to the

outpatient department or emergency room of a hospital in Meerut, Uttar

Pradesh, India.

Results: Rotavirus accounted for 26.3% (51 of

194) of diarrhea cases overall, and 41.2% (14 of 34) in hospitalized

children. Rotavirus infection was associated with significantly longer

duration [3.3 (1.4) d vs. 2.5 (1.1) d; P=0.004) of

diarrhea, and more chances of dehydration (OR 1.85; 95% CI 1.19, 3.57)

as compared to non-rotavirus diarrhea.

Conclusion: Rotavirus is a common cause of acute

diarrhea in under-five children, and is associated with a longer

duration and more chances of dehydration than non-rotavirus diarrhea.

Keywords: Acute diarrhea, Epidemiology, Etiology.

|

|

Rotavirus is a common cause of diarrhea in

children below 5 years of age, and is estimated to cause 4.4% and 3.2%

of deaths worldwide in children in age group below one year and 1-4

years, respectively [1]. India has estimated annual burden of 2.0-3.4

billion cases attributable to rotavirus [2]. A rising trend in

proportion of rotavirus cases in hospitalized children has been

reported; 26.1% before 2000 to 38.3% after 2005 [3]. A recent

multi-centric surveillance study in India reported 39% prevalence of

rotavirus in children below five years of age hospitalized for acute

diarrhea [4]. World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that State of

Uttar Pradesh (UP) in India accounts for 32% of diarrheal deaths due to

rotavirus infection among Indian children younger than five years [5].

As UP was not included in rotavirus multi-centric surveillance study, it

is pertinent to collect information related to rotavirus diarrhea from

this region. The present study was designed to estimate the proportion

of rotavirus diarrhea in children presenting with acute diarrhea, and to

study its clinical profile.

Methods

This descriptive study was conducted in the

Department of Pediatrics, LLRM Medical College, Meerut, UP, India from

July 2011 to June 2012. Children aged between 6 months to 5 years

presenting with acute diarrhea (<7 days duration), irrespective of

hydration status, to the outpatient department (OPD) or emergency room

of hospital were eligible for inclusion. Diarrhea was defined as passage

of three or more loose stools in the last 24 hours [6]. Children with

severe malnutrition (weight-for-height <-3 SD of WHO charts), dysentery

and clinical evidence of coexisting acute or chronic systemic illnesses

were excluded from the study. Written informed consent was obtained from

parents of children enrolled in the study.

All children were managed according to their

dehydration status, as per WHO guidelines [6]. Children were monitored

for number of loose stools, consistency of stool and time since last

loose stool every six hours in a day. Children admitted in emergency

ward were monitored directly by doctor on duty. Those who were enrolled

on outpatient basis were contacted telephonically till diarrhea

resolved, or for a period of 7 days after enrolment, whichever was

earlier.

Stool samples of enrolled children were collected in

sterile screw-top container, and were stored at -20° C till testing.

Rotavirus detection was done only in children who completed the 7-day

follow-up. Samples were transported to Microbiology department of our

hospital in vaccine carrier; rotavirus detection was done by ELISA using

Rota IDEIA Kit (DAKO, Germany).

Data were entered in the Microsoft Excel worksheet

and were analyzed using SPSS Version 17.0.

Results

Over a 12-month period, 516 children (444 OPD and 72

Emergency services) with acute diarrhea presented to the hospital, out

of which 254 eligible children were enrolled in the study. Among

included patients, 170 patients were also part of another study to

determine the effect of probiotics on acute childhood diarrhea [7].

Stool sample analysis for rotavirus could be done only for 194 patients;

165 (85.1%) were enrolled from OPD and 29 (14.9%) from the emergency

(overnight hospital stay). The mean (SD) age was 19.1 (13.5) months, and

children aged 6-23 months accounted for 79.5% of all included children.

Some dehydration was seen in 40.7%, severe hydration in 5.1% and

vomiting in 37.8% of participants. Thirty-six (14.6%) children required

intravenous fluids for dehydration correction, and one child died 6

hours after admission in emergency services. None of the included

children was vaccinated with rotavirus vaccine.

|

|

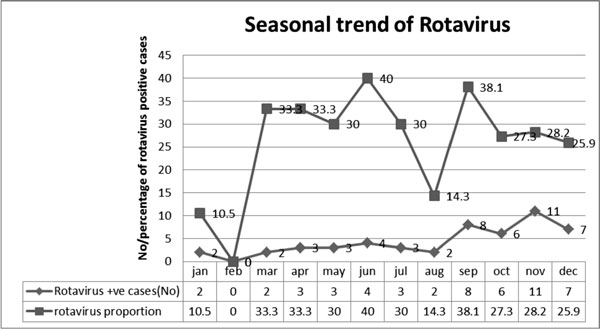

Fig. 1 Month-wise rotavirus positivity

in study children.

|

Rotavirus was detected in 51 out of 194 (26.3%)

children with acute diarrhea. Fig. 1 depicts the

month-wise detection of rotavirus antigen in study children. Among

hospitalized children, rotavirus was detected in 14 out of 34 (41.2%).

Most (82.3%) rotavirus-positive cases occurred in the age group of 6–23

months. Rotavirus positivity rate did not differ significantly by sex

(34.7% among boys vs. 24.3% among girls). Table I

compares clinical profile of diarrhea in children with rotavirus

positive and rotavirus negative status. Children with rotavirus diarrhea

had a longer duration of diarrhea and were more likely to be dehydrated

than those with rotavirus-negative disease [dehydrated (56.8%) vs.

non- dehydrated (43.2%); OR 1.85; 95% CI 1.19, 3.57; P=0.021].

Fever was observed in 72.5% (37 of 51) children with rotavirus diarrhea

and 48.9% (70 of 143) without rotavirus diarrhea.

TABLE I Clinical Profile of Children with Rotavirus Diarrhea

|

Variable |

Rotavirus positive |

Rotavirus negative |

P value |

OR (95% CI) |

|

Age < 2 y |

42 (82.3) |

94 (65.7) |

0.02 |

2.41 (1.10, 5.26) |

|

Winter season (Nov-Feb) |

26 (50.9) |

69 (48.3) |

0.89 |

1.11 (0.48, 2.20) |

|

Fever |

37 (72.5) |

70 (48.9) |

0.004 |

2.75 (1.37, 5.53) |

|

Dehydrated |

29 (56.9) |

56 (42.0) |

0.02 |

1.85 (1.19, 3.57) |

|

#Loose stools per day |

9.8 (2.1) |

9.6 (2.2) |

0.83 |

0.33 (-0.44, 0.93)* |

|

#Duration of hospital stay (h) |

76.1(27.7) |

76.5 (17.7) |

0.97 |

-0.36 (-16.19, 15.48)* |

|

#Duration of diarrhea at time of enrolment (d) |

3.3 (1.4) |

2.5 (1.1) |

0.004 |

1.25 (0.90-1.64) |

|

#Total duration of diarrhea (d) |

6.3 (1.6) |

5.3 (1.4) |

0.02 |

1.55 (1.09, 2.00)* |

|

Data in No. (%) or #Mean (SD); *Mean difference (95% CI). |

Discussion

Rotavirus infection is the most common cause of

severe gastroenteritis in children below five years of age in most

regions of India [8-10]. The present study demonstrated that rotavirus

accounts for approximately one-fourth of acute diarrhea among children

presenting to hospital below 5 years of age. The proportion was higher

(41.2%) in hospitalized children, and those with rotavirus diarrhea had

a longer duration of diarrhea and were more likely to be dehydrated.

Kang, et al. [2] detected rotavirus in 39%

cases in Indian multi-centric surveillance whereas Bahl, et al.

[8] reported 23.5% positivity rate in children below 5 years,

hospitalized for acute diarrhea. A review of 46 epidemiological studies

reported rotavirus in 20% of children hospitalized for acute diarrhea

[10]. The difference observed between our study and previous studies may

be attributed to variation in enrolment criteria among the studies, and

inclusion of outpatient children in our study. Like previous studies

[2,11], we also found more dehydration and longer duration of diarrhea

in rotavirus-positive children.

Main limitations of our study were hospital-based

enrolment and absence of asymptomatic control group. Rotavirus detection

was done only in children completing the follow-up, which might have

affected the calculation of the correct positivity rate. Also, we did

not look for other etiological agents causing diarrhea. A recent study

from Kolkata reported that 57.8% cases positive for rotavirus were

co-infected with other pathogens.

We conclude that rotavirus is responsible for about

one-fourth of childhood diarrhea under age of five years, and is

associated with significant risk of dehydration and prolonged diarrhea.

Contributors: AU and DS: conceived and designed

the study and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content;

NT, SA collected the data and drafted the paper; DS: analyzed the data

and provided critical review for revision of manuscript; AG performed

the laboratory work, and provided critical inputs. The final manuscript

was approved by all authors.

Funding: None; Competing interest: None

stated.

References

1. Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K,

Aboyans V, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes

of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: A systematic analysis for

the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2095-128.

2. Tate JE, Chitambar S, Esposito DH, Sarkar R,

Gladstone B, Ramani S, et al. Disease and economic burden of

rotavirus diarrhoea in India. Vaccine. 2009;27:18-24.

3. Kahn G, Fitzwater S, Tate J, Kang G, Ganguly N,

Nair G, et al. Epidemiology and prospects for prevention of

rotavirus disease in India. Indian Pediatr. 2012;49: 467-74.

4. Kang G, Arora R, Chitambar SD, Deshpande J, Gupte

MD, Kulkarni M, et al. Multicenter, hospital-based surveillance

of rotavirus disease and strains among Indian children aged <5 years. J

Infect Dis. 2009;200:147-53.

5. Morris SK, Awasthi S, Khera A, Bassani DG, Kang

G, Parashar UD, et al. Rotavirus mortality in India: Estimates

based on a nationally representative survey of diarrhoeal deaths. Bull

World Health Organ. 2012;90: 720-7.

6. Arora NK, Das MK, Mathur P. Diseases of

Gastrointestinal Tract and Liver. In: Ghai OP, Paul VK, Bagga A,

editors. Ghai Essential Pediatrics. 7th ed. Delhi: CBS

Publishers; 2009. p. 251-95.

7. Aggarwal S, Upadhyay A, Shah D, Teotia N, Agarwal

A, Jaiswal V. Lactobacillus GG for treatment of acute childhood

diarrhoea: An open labelled, randomized controlled trial. Indian J Med

Res. 2014;139:379-85.

8. Bahl R, Ray P, Subodh S, Shambharkar P, Saxena M,

Parashar U, et al. Incidence of severe rotavirus diarrhea in New

Delhi, India, and G and P types of infecting strains. J Infect Dis.

2005;192:114-9.

9. Banerjee I, Ramani S, Primrose B, Moses P,

Iturriza-Gomara M, Gray JJ, et al. Comparative study of the

epidemiology of rotavirus in children from a community-based birth

cohort and a hospital in South India. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:2468-74.

10. Ramani S, Kang G. Burden of disease and molecular

epidemiology of group A rotavirus infections in India. Indian J Med Res.

2007;125:619-32.

11. Gladstone BP, Ramani S, Mukhopadhya I, Muliyil J,

Sarkar R, Rehman AM, et al. Protective effect of natural

rotavirus infection in an Indian birth cohort. N Engl J Med.

2011;365:337-46.

|

|

|

|

|