|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2016;53:

70-72 |

|

Gastrointestinal Neuroendocrine Tumors in Two

Children

|

|

Tugba Koca, Selim Dereci, *Nermin

Karahan and Mustafa Akcam

From Departments of Pediatrics, Division of Pediatric

Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, and *Department of

Pathology; Faculty of Medicine, Suleyman Demirel University, Isparta,

Turkey.

Correspondence to: Dr Tugba Koca, Department of Pediatrics, Suleyman

Demirel University Faculty of Medicine, Cunur, Isparta, Turkey.

[email protected]

Received: February 23, 2015;

Initial review: April 27, 2015;

Accepted: October 27, 2015.

|

|

Background: Enterochromaffin-like cell hyperplasia and

neuroendocrine tumors are relatively rare in childhood.Case

characteristics: A 15-year-old girl who presented with epigastric

pain and a 6-year-old boy who was admitted with hematochezia. Endoscopy

revealed nodules in the stomach in Case 1, and polyploidy lesion in the

rectum in Case 2. Outcome: Enterochromaffin-like cell hyperplasia

in Case 1 and neuroendocrine tumor in Case 2. Message: A low

index of suspicion for neuroendocrine tumors in children can result in

delay in the detection of these rare but potentially malignant diseases.

Key words: Abdominal pain, H. pylori,

Hemtochezia.

|

|

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) – slow-growing tumors

that arise from cells within the neuroendocrine system — are rarely seen

in childhood [1,2]. The incidence in children and adolescents is low at

2.8 per million population under the age of 30 years. Despite their low

incidence, NETs represent the most frequent tumor of the

gastrointestinal tract in children [3].

Enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cell hyperplasia

constitutes the substrate for the development of gastric NETs type 1,

which represents the most common (65–75%) type of gastric NETs. There is

increasing diagnosis of NETs of the colon and rectum [4]. We present two

cases of NETs and ECL cell hyperplasia.

Case Reports

Case 1: A 15-year-old girl presented with a

3-month history of epigastric pain which was unresponsive to a 2-month

course of proton pump inhibitor (PPI). Physical examination was

unremarkable. Complete blood count, metabolic panel, lipase, C-reactive

protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and celiac serology were

normal. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed numerous 2 to 4 mm nodules

in the body of the stomach and in the transitional and pyloric region.

The histopathological investigation demonstrated focal intestinal

metaplasia and ECL cell hyperplasia in the stomach. Synaptophysin

staining highlighted an increase in ECL cells within the glands (linear

hyperplasia) and florets of ECL cells in the lamina propria (nodular

hyperplasia) (Fig. 1). Helicobacter pylori staining

was positive. Further laboratory evaluation revealed serum gastrin:

293.6 pmol/L (Normal 6.2-54.8), anti thyroglobulin: 322.7 IU/mL (Normal

0-115), and anti-Jo-1 positive. Serum vitamin B 123,

and free serum T4 levels

were normal. The PPI treatment was stopped after the result of the serum

gastrin level was available. An abdominal computed tomography scan was

normal. The secretin stimulation test was negative. Endoscopic and

pathological investigations were repeated one year after diagnosis.

H. pylori staining was negative and the histopathological findings

were similar to those seen on the earlier biopsies. In the second year

of follow-up, she had no significant abdominal pain. Third

esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed multifocal atrophic gastritis and

focal intestinal metaplasia. ECL cell hyperplasia was identified in the

cardia, corpus and antrum-corpus junction. Additional laboratory reports

included anti-parietal cell antibodies positive and chromogranin A

elevated at 298.5 ng/mL (Normal 0-100). Serum gastrin level was high

(376 pmol/L) despite no use of PPI after the diagnosis. Given her

negative evaluation for H. pylori, positive anti-parietal cell

antibodies and gastric pathology, the patient was diagnosed with

autoimmune metaplastic atrophic gastritis (AMAG) with associated ECL

cell hyperplasia.

|

|

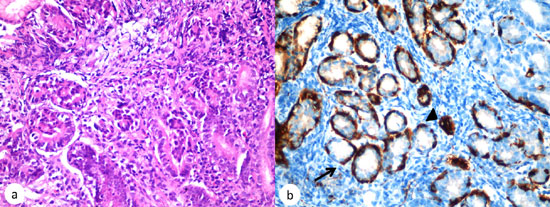

Fig. 1. (a)

Histopathology (Hematoxyline and eosin, X400) demonstrating

enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cell hyperplasia; (b),

Synaptophysin stain demonstrating both linear (arrow) and

nodular (arrowhead) patterns of ECL cell hyperplasia in the body

of the stomach (x 400).

|

Case 2: A 6-year-old boy was admitted with

abdominal pain for two weeks and hematochezia for 2 days. The physical

examination, upper gastrointestinal system endoscopy, routine laboratory

findings and Meckel scintigraphy were unremarkable. Colonoscopy revealed

polyploid architecture (0.6 cm in diameter) located in the rectum and 5

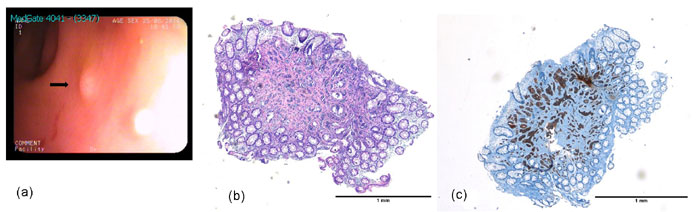

cm from the anal verge (Fig. 2a). Endoscopic resection was

performed and the histopathological examination was consistent with a

NET (Fig. 2 b and 2c). Hematochazia was not observed

during the hospitalization period. Due to the low risk of metastatic

spread, and as the tumors were small (<1 cm, without muscularis

invasion), we planned to perform endoscopic investigation every year.

|

|

Fig. 2. (a) Endoscopic view of

polyploid architecture (0.6 cm in diameter) located in the

rectum (black arrow); (b) Hematoxylin and eosin stain of the

colon demonstrating NET; (c), Synaptophysin stain demonstrating

NET in the rectum.

|

Discussion

There are three situations in which clinicians

suspect ECL-cell hyperplasia. The simplest is when a nodule or polyp is

identified by the endoscopist. The second situation involves the

evaluation of gastric atrophy, and finally in PPI use as a result of

iatrogenic hypergastrinemia [5]. Initially, atrophic gastritis was not

determined in case 1, although she had nodules in the stomach with

history of PPI use.

Neuroendocrine nests are seen on the hematoxylin and

eosin-stained sections; there is no need to perform special staining.

ECL cells, typically found in the gastric corpus, are rare or absent in

other compartments of the stomach [5]. ECL cells were identified in the

cardia, corpus and antrum-corpus junction in Case 1. Long-standing

hypergastrinemia and, acid suppression exerts a proliferative pressure

on ECL cells, especially in the presence of H. pylori infection

[6]. The time of ECL hyperplasia regression after H. pylori

eradication is not known. In Case 1, there was PPI use together with

H. pylori infection. At follow-up, 1 year after diagnosis, H.

pylori was negative in the endoscopy examination but ECL had not

regressed. Surveillance endoscopic biopsy revealed H. pylori–negative

atrophic gastritis.

To date, there have been few published information

regarding ECL cell hyperplasia in children [7]. ECL hyperplasia together

with autoimmune thyroid disease and autoimmune gastritis has been

previously reported [8]. Anti-thyroglobulin antibody was positive in

case 1. Colonic and rectal NETs are also very rare in children [9]. Due

to the low risk of metastatic spread, tumors that are small and confined

to the mucosa or submucosa can be managed with endoscopic resection.

Hindgut NETs have a substantial risk of relapse after resection and need

to be followed up for at least 7 years [4]. In case 2, a small rectal

tumor (<1 cm, without muscularis invasion) was excised, and it was

planned to perform endoscopic investigation every year.

Chromogranin A levels correlate positively with ECL

cell mass in patients with AMAG [10]. Only a small fraction of hindgut

NETs produce and secrete serotonin or other bioactive hormones [3].

In conclusion, gastric NETs are usually solitary and

large and have frequently metastasized by the time of presentation.

Pediatric gastroenterologists and pathologists must be aware that NETs

can begin at a young age, and their immediate precursors such as ECL

cell hyperplasia develop in the pediatric age group.

Contributors: TK: management of cases; TK,

SD: wrote the manuscript; MC, NK: evaluated the histological

preparations; MAK: case management and final approval of manuscript.

Funding: None; Competing interest: None stated.

References

1. Li T, Qiu F, Qian ZR, Wan J, Qi XK, Wu BY.

Classification, clinicopathologic features and treatment of gastric

neuroendocrine tumors. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:118-25.

2. Sarvida ME, O’Dorisio MS. Neuroendocrine tumors in

children and young adults: Rare or not so rare. Endocrinol Metab Clin N

Am. 2011;40:65-80.

3. Howell DL, M. Sue O’Dorisio MS. Management of

neuroendocrine tumors in children, adolescents, and young adults. J

Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012;34:64-8.

4. Anthony LB, Strosberg JR, Klimstra DS, Maples WJ, O’Dorisio

TM, Warner RR, et al. The NANETS Consensus Guidelines for the

Diagnosis and Management of Gastrointestinal Neuroendocrine Tumors

(NETs): Well-differentiated nets of the distal colon and rectum.

Pancreas. 2010;39:767-74.

5. Cockburn AN, Morgan CJ, Genta RM. Neuroendocrine

Proliferations of the Stomach: A pragmatic approach for the perplexed

pathologist. Adv Anat Pathol. 2013;20:148-57.

6. Waldum HL, Hauso Ř, Fossmark R. The regulation of

gastric acid secretion - clinical perspectives. Acta Physiol (Oxf).

2014;210:239-56.

7. Yang R, Cheung MC, Zhuge Y, Armstrong C, Koniaris

LG, Sola JE. Primary solid tumors of the colon and rectum in the

pediatric patient: A review of 270 cases. J Surg Res. 2010;161:209-16.

8. Alexandraki KI, Nikolaou A, Thomas D, Syriou V, Korkolopoulou

P, Sougioultzis S, et al. Are patients with autoimmune thyroid

disease and autoimmune gastritis at risk of gastric neuroendocrine

neoplasms type 1? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2014;80:685-90.

9. Johnson PR. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine

(carcinoid) tumors in children. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2014;23:91-5.

10. Peracchi M, Gebbia C, Basilisco G, Quatrini M,

Tarantino C, Vescarelli C, et al. Plasma chromogranin A in

patients with autoimmune chronic atrophic gastritis, enterochromaffin-like

cel lesions and gastric carcinoids. Eur J Endocrinol. 2005;152:443-8.

|

|

|

|

|