|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2016;53:

39-41 |

|

Association Between

Metabolic Control and Lipid Parameters in Indian Children with

Type 1 Diabetes

|

|

Lavanya Parthasarathy, Shashi Chiplonkar, Vaman

Khadilkar and Anuradha Khadilkar

From Hirabai Cowasji Jehangir Medical Research

Institute, Jehangir Hospital, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Anuradha Khadilkar, Hirabai

Cowasji Jehangir Medical Research Institute, Jehangir Hospital, 32

Sassoon Road, Pune.411 001, India.

Email:

[email protected]

Received: April 07, 2015;

Initial review: June 08, 2015;

Accepted: October 28, 2015.

|

Objectives: To compare lipid parameters between diabetics and

controls and to study association between metabolic control and lipid

profile.

Methods: Lipid profile and HbA1c were measured (n=80,

39 boys) in diabetic children [age 10.7(3.4) y] and 54 controls, tests

repeated after 1 year (in 45 diabetics).

Results: Diabetic children had higher mean (SD)

LDL-C [95.3(27.7) vs 84.5(26.4) mg/dL], lower HDL-C [48.2 (13.1)

vs 53.1(11.9) mg/dl]. Moderate physical activity (P=0.014)

protected against high LDL-C levels. HbA1c (P=0.00) predicted

total and LDL-C levels. At 1year, 63% showed reduced LDL-C with

improving HbA1c; 72% showed increased LDL-C with deteriorated HbA1c.

Conclusion: Improving metabolic control is

cardinal to reduce cardiometabolic risk; physical activity is

beneficial.

Keywords: Cardiometabolic risk, Hyperlipidermic, Metabolic

control, Prognosis.

|

|

I

mpaired lipid metabolism resulting from

uncontrolled hyperglycemia is implicated in cardiovascular complications

in diabetes. Deranged lipids have been reported amongst adolescents and

youth in the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth study [1]. Although data on

the influence of blood glucose control on development of atherosclerosis

is conflicting, there is increasing evidence of an association between

the two [2-5].

This study was conducted to i) compare lipid

parameters between diabetic children and controls; ii) determine

factors influencing lipid parameters in diabetic children; and iii)

examine effect of lowering of glycosylated hemoglobin on lipids in

diabetic children at one year.

Methods

This cross-sectional study with one-year follow-up

was done after institutional ethical committee clearance. Considering

variability in LDL-C reported in past studies [6], a sample size of 80

diabetics and 54 controls was found to have a power of 0.8 at 5% level

of significance and 3% margin of error. Families with diabetic children

aged 5 to 17 years attending the diabetes clinic at our institution were

approached, and a random sample of 80 (39 boys) were enrolled

prospectively (May 2013 to October 2014). Age- and gender-matched

healthy controls were recruited from private schools. Patients with

known chronic disorders were excluded. Data on medications, age at onset

and duration of diabetes and insulin regimen were collected in a

standardized form and verified from hospital records.

Anthropometric data were collected using standard

methods and were converted to Z scores [7]. Fasting blood sample was

collected to measure HbA1c by HPLC (BIO-RAD, Germany) and lipid profile

(enzymatic method). The GE-Lunar DPX Pro (GE Healthcare, Wisconsin, USA)

was used to measure body composition. Dietary intakes were assessed by

24-hour recall on three random days (non-consecutive)/week, including

one holiday. Nutrient intakes were calculated (CDIET, Version 2, Xenios

Technologies, Pune, India). Physical activity data were collected using

validated activity questionnaires [8,9] adapted for Indian children.

Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS for

Windows 12 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Anthropometry, biochemical

parameters and body composition were recorded in 45 (20 girls) children

who regularly attended the clinic at the end of one year.

Results

Table I summarizes the anthropometric, body

composition and biochemical parameters. There were no significant

differences between sexes for anthropometric and biochemical parameters

(P>0.05). Hence, further analysis was performed on pooled data.

TABLE I Anthropometry, Body Composition and Biochemical Parameters in Study Participants

|

Cases (n=80) |

Controls (n=54) |

|

Age (y) |

10.7 (3.4) |

11.7 (2.8) |

|

Height (cm) |

132.3 (18.1) |

144.7* (15.2) |

|

Weight (kg) |

28.9 (11.8) |

35.0* (11.2) |

|

BMI (kg/m2) |

15.6 (3.1) |

17.1 (5.8) |

|

Height for Age Z Score |

–0.9 (1.1) |

0* (0.9) |

|

Weight for Age Z Score |

–1 (0.9) |

–0.8 (3.4) |

|

BMI for Age Z Score |

–0.7 (0.8) |

–1.3 (5.7) |

|

Lean Mass% |

73.9 (9.0) |

70.7 (9.0) |

|

Total Body Fat% |

20.3 (9.1) |

26.5* (12) |

|

Android Fat% |

21.9 (10.3) |

29.1* (13.3) |

|

Gynoid Fat% |

33 (8.8) |

35.8 (9.9) |

|

Cholesterol (mg/dL) |

157.7 (33.5) |

153.5 (27.7) |

|

Triglyceride (mg/dL) |

71 (26.5) |

71.5 (30.5) |

|

HDL (mg/dL) |

48.2 (13.1) |

53.1* (11.9) |

|

VLDL |

14.3 (5.4) |

14.3 (6.1) |

|

LDL (mg/dL) |

95.3 (27.7) |

84.5* (26.4) |

|

Cholesterol/HDL ratio |

3.4 (0.8) |

3* (0.8) |

|

LDL/HDL ratio |

2.1 (0.7) |

1.7* (0.7) |

|

HbA1c% |

10 (2) |

- |

|

*significantly different between diabetic children and

controls (P<0.05); #significantly different between

HbA1c>median group and controls (P<0.05). |

35% diabetic children had high LDL-C, 18% had low

HDL-C and 2% had high triglycerides [10]. HDL-C was significantly lower

and LDL-C was significantly higher in diabetic children. Mean (SD) HbA1c

of diabetic children was 10 (2), signifying suboptimal blood glucose

control.

Using linear regression, metabolic control (HbA1c) (P=0.002)

was identified as positive predictor and age at diagnosis (P=0.012)

as a negative predictor of total cholesterol. For LDL-C, metabolic

control (P=0.001) and age at diagnosis (P=0.027) were

predictors. Total body fat % or android fat % did not affect lipid

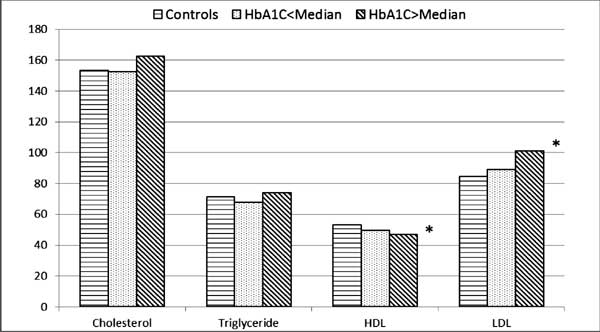

profile. When diabetic children were divided into two groups according

to median HbA1c (9.7%) and then compared to controls, diabetic children

with HbA1c above median had significantly higher LDL-C and lower HDL-C

as compared to controls (Fig. 1).

|

|

Fig. 1 Comparison of lipid

profile parameters between groups of diabetic children according

to HbA1C and controls.

|

To study impact of lifestyle factors on lipid

profile, linear regression models were utilized. Mean (SD) daily intake

of energy was 1632 (43) Kcal, protein was 44 (12) g, fat was 45 (12) g

and carbohydrate was 267 (75) g. Mean (SD) time spent in moderate

activities by children was 37 (25) min/d. Moderate physical activity (P=0.014)

was identified as protective factor against LDL-C. Dietary intakes did

not affect any of the lipid profile parameters.

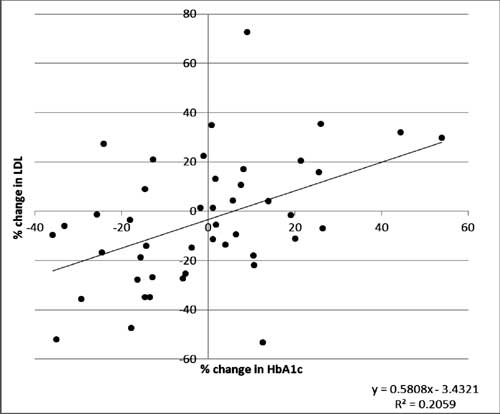

Follow-up: Lipid profile parameters and HbA1c

were repeated after one year in a subset of diabetic children (n=45)

and percentage change of LDL-C and HbA1c were computed. A positive

association (r 2=0.2059)

between percentage change in LDL-C and HbA1c was seen (Fig. 2).

In the group of children whose metabolic control improved, 63% children

showed a reduction in LDL-C levels. Whereas, in the group where the

metabolic control deteriorated, 72% children showed increase in LDL-C.

|

|

Fig. 2 Relationship between

percentage change of LDL-C and HbA1c over the one year period.

|

Discussion

Our cross-sectional data shows that Indian children

and adolescents with type 1diabetes have deranged lipids as compared to

healthy controls. Deterioration was related to poor metabolic control

and age at diagnosis. Physical activity was protective against LDL-C.

One year follow-up data showed deterioration in HbA1c to be associated

with an increase in LDL-C and vice versa.

One of the important factors contributing to

variations in lipid profile amongst children could be family history of

the child. We did not have information regarding the parent’s lipid

profile parameters or their risk for CVD. Hence, we could not adjust for

this during analysis. Although our data support the relationship between

poor metabolic control and increase in LDL-C, our sample size for the

follow-up study is small, and studies with larger sample size are

required to confirm our findings.

Interference in normal physiology of low-density

lipoprotein (LDL) particle has been reported by studies in the past

which suggest that in patients with type 1 diabetes, LDLs are often

enriched in triglycerides and increased number of small dense LDL

particles are observed. Our data are in keeping with findings of Guy,

et al. [2] and Petitti, et al. [5] who have also reported

high LDL-C among children with Type 1 diabetes.

Advantages of physical activity in diabetes

management have been previously reported [11-13]. In our study as well,

children who engaged in moderate physical activity for more than half an

hour each day had lower LDL-C. Hence, encouraging children to

participate in various forms of physical activity may be beneficial in

reducing the risk of CVD in future.

In conclusion encouraging a healthy lifestyle

with adequate physical activity and improving metabolic control is

recommended for reducing dyslipidemia in children with diabetes.

Children diagnosed younger are more likely to have deranged lipids and

thus are at increased cardiometabolic risk.

Contributors: LP, AK, VK: conceptualized the

study, and analyzed data; SC: performed statistical analyses. All

authors contributed to the manuscript and approved its contents.

Funding: Mr. Pancharatnam; Ms Lavanya

Parthasarathy was funded by a fellowship grant from the University

Grants Commission, Government of India.

Competing interests: None stated.

|

What This Study Adds?

• Children diagnosed at younger years are at

higher risk of deranged lipid parameters.

• Physical activity is a protective factor against desanyed

lipid profile.

|

References

1. Kershnar AK, Daniels SR, Imperatore G, Palla SL,

Petitti DB, Pettitt DJ, et al. Lipid abnormalities are prevalent

in youth with type 1 and type 2 diabetes: the SEARCH for Diabetes in

Youth study. J Pediatr. 2006;149:314-9.

2. Guy J, Ogden L, Wadwa RP, Hamman RF, Mayer-Davis

EJ, Liese AD, et al. Lipid and lipoprotein profiles in youth with

and without type 1 diabetes: the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth

case-control study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:416-20.

3. Ladeia AM, Adan L, Couto-Silva AC, Hiltner A,

Guimarães AC. Lipid profile correlates with glycemic control in young

patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus.Prev Cardiol. 2006;9:82-8.

4. Petitti DB, Imperatore G, Palla SL, Daniels SR,

Dolan LM, Kershnar AK, et al. SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study

Group. Serum lipids and glucose control: the SEARCH for Diabetes in

Youth study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:159-65.

5. Schwab KO, Doerfer J, Naeke A, Rohrer T, Wiemann

D, Marg W, et al. ; German/Austrian Pediatric DPV Initiative.

Influence of food intake, age, gender, HbA1c, and BMI levels on plasma

cholesterol in 29,979 children and adolescents with type 1

diabetes—reference data from the German diabetes documentation and

quality management system (DPV). Pediatr Diabetes. 2009;10:184-92.

6. Babar GS, Zidan H, Widlansky ME, Das E, Hoffmann

RG, Daoud M, et al. Impaired endothelial function in

preadolescent children with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care.

2011;34:681-5.

7. Khadilkar VV, Khadilkar AV, Cole TJ, Sayyad MG.

Cross-sectional growth curves for height, weight and body mass index for

affluent Indian children, 2007. Indian Pediatr. 2009;46:477-89.

8. Barbosa N, Sanchez CE, Vera JA, Perez W, Thalabard

JC, Rieu M. A physical activity questionnaire: Reproducibility and

validity. J Sports Sci Med. 2007;6:505-18.

9. CDC, 1999. Available from: www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/

dnpa/ physical/pdf/PA_Intensity_table_2_1.pdf. Accessed December 22,

2013.

10. American Diabetes Association. Management of

dyslipidemia in children and adolescents with diabetes. Diabetes Care.

2003;26:2194-7.

11. Beraki A, Magnuson A, Särnblad S, Åman J,

Samuelsson U. Increase in physical activity is associated with lower

HbA1c levels in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes: results

from a cross-sectional study based on the Swedish Pediatric Diabetes

Quality Registry (SWEDIABKIDS). Diabetes Res Clin Pract.

2014;105:119-25.

12. Quirk H, Blake H, Tennyson R, Randell TL,

Glazebrook C. Physical activity interventions in children and young

people with Type 1 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review with

meta-analysis. Diabet Med. 2014;31:1163-73.

13. Leclair E, de Kerdanet M, Riddell M, Heyman E.

Type 1 diabetes and physical activity in children and adolescents. J

Diabetes Metab. 2013;S10:004.

|

|

|

|

|