|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2014;51: 45-47 |

|

Modifiable Factors for Prevention of Childhood

Mortality

|

|

Vidushi Mahajan, Amarpreet Kaur, Amit Sharma,

Chandrika Azad and Vishal Guglani

From Department of Pediatrics, Government Medical

College and Hospital, Sector 32, Chandigarh, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Vidushi Mahajan, Assistant

Professor, Department of Pediatrics, Government Medical College and

Hospital, Sector 32, Chandigarh, India.

Email:

vidushimahajan2003@yahoo.co.in

Received: February 1, 2013;

Initial review: March 04, 2013;

Accepted: July 05, 2013.

Published online: August 05, 2013.

PII: S097475591300104

|

|

Objective: To know the

disease-related causes of child mortality and identify socially

modifiable factors affecting child mortality among hospitalized children

aged >1 month-18 years in a referral hospital of North India.

Methods: Causes of death (ICD-10 based) were extracted

retrospectively from hospital files (n=487) from 17 March 2003 to

30 June 2012. Modifiable factors were prospectively studied in 107

consecutive deaths from 6 October 2011 to 30 June 2012. Results:

Pneumonia, CNS infections and diarrhea were the most common

disease-related causes of child mortality. Conclusions: Amongst

modifiable factors, administrative issues were most common followed by

family-related reasons and medical-personnel related problems.

Keywords: Audit, Child deaths, India,

Prevention.

|

|

India hosts maximum (24%) number of deaths in

under-5 children occurring worldwide [1]. Disease-related or

‘biological’ factors related to child mortality are studied extensively.

Majority of childhood deaths in India are attributed to infections,

particularly pneumonia and diarrhea [1- 6]. Certain non-biological

causes (e.g. administrative, medical personnel, family-related

factors) may also contribute towards child mortality [7]. We planned

this study to evaluate disease-related causes and modifiable factors of

child mortality among hospitalized children aged >1 month-18 years who

died in a tertiary care referral teaching hospital of Northern India.

Methods

The study had a mixed design; disease-related causes

of mortality were analyzed retrospectively (17

March, 2009 to 30

June, 2012) and socially modifiable factors were

identified prospectively (6

October, 2011 to 30 June,

2012) in children (age 1 mo-8 y), who died in Pediatric emergency ward

(PEW) and Pediatric Intensive care unit (PICU). Ethical approval was

obtained.

To study the disease-related causes of mortality, we

extracted the relevant clinical details and final diagnosis from

hospital files of the study population. We excluded any missing case

records. The ‘primary cause’ of death was the probable cause that

finally led to death of the child [8]. The causes of death were ICD-10

based.

To study the modifiable causes of child mortality, we

enrolled all critically sick children admitted in PEW and PICU. A list

of modifiable factors was developed a. priori, which were defined

as events, actions or omissions contributing to death of a child and

which, by means of interventions, could be modified [9]. These factors

were categorized as: (A) Family/caregiver-related problems which

included - (i) delay in getting medical attention (e.g.

lack of transport, girl child, delayed referral by primary care

physician, inability to recognize danger signs, maternal ill health), (ii)

treatment by quacks/faith healers, (B) Medical personnel-related factors

included - (i) clinical assessment issues (delay in detection of

signs, delayed referral by treating team, alternative diagnosis not

considered), (ii) monitoring issues, and (iii) case

management (prescription error, delay in institution of specific

management) at our hospital; and (C) Administrative factors included -

(i) shortage of staff (residents, nurses), (ii)

shortage/non-functioning of equipment(s), (iii) lack of

specialized lifesaving care e.g. dialysis, surgical procedure

etc, (iv) lack of PICU beds/ ventilators, (v)

communication gap between medical staff, (vi) Lack of drugs,

blood products, and (vii) lack of policy. Resident doctors

recorded these factors during history-taking, which were cross-checked

by a consultant pediatrician. The staff was periodically primed to

record all study variables.

To identify modifiable factors audit meetings were

held fortnightly, using death-audit profoma and patient records. Each

meeting was attended by at least three consulting pediatricians (one

primary consultant who managed the case and two unrelated consultants),

concerned resident doctors and nursing staff, where deemed necessary.

Consensus on causes of death, contributing conditions and modifiable

factors were reached.

Proportion of disease-related causes of mortality;

and proportion of modifiable factors related to child mortality were the

two outcome variables. Descriptive statistics was used to describe

baseline demographic variables and modifiable factors. Data were

analysed by Excel and SPSS V. 17.0.

Results

There were 5815 admissions (>1 month) during the

study period. Of these, 493 children died (case fatality rate 8.4%). We

excluded six cases whose files could not be traced. We therefore

analyzed 487 deaths [237 (48.6%) one-month to 1-year, 138 (28.3%) in 1-5

years and 112 (23%) in children >5 years] for disease-related causes of

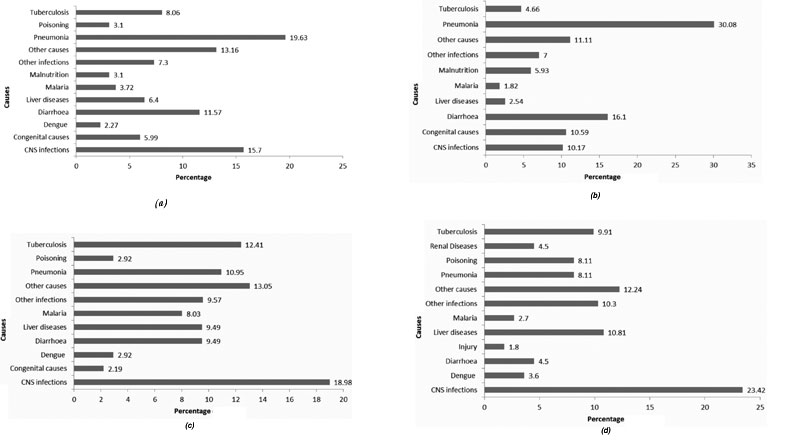

mortality. Pneumonia, CNS infections and diarrhea were leading

disease-related causes of mortality (Fig. 1). Severe

malnutrition (42%) was the major contributing cause [median z–score:

-1.94 (IQR -3.37 to -0.68)].

|

|

Fig. 1 Causes of deaths in (a)

children of all ages (N=487) (b) children 1-12 months (N=237)

(c) children 1-5 years (N=138) (d) children above 5 years

(N=112).

|

We studied modifiable factors amongst 107 (5% males)

consecutive deaths. Their median (IQR) age was 12 (5, 60) months and

weight was 8 (5, 15) kg. 43% had shock at presentation, as defined by

AHA [10,11], and 6% had a cardiac arrest either before or at

presentation to PEW. Seventy one percent required mechanical

ventilation within one hour of presentation. Median

hospital stay was 32 (IQR-10, 101) hours. Majority (64%) of the parents

of study children lived in villages, were illiterate (mothers-46%,

fathers-29%) and worked as manual labourers/ daily wagers (61%).

Amongst modifiable factors, administrative issues

were most common (universal) followed by family/caregiver-related

factors (72%) and medical personnel-related factors (41%). Shortage of

medical personnel especially senior residents and nursing staff remained

a constant feature throughout. Among medical personnel-related factors,

improper monitoring was single most prevalent factor. (Table I).

TABLE I Modifiable Factors Among 107 Deaths

|

Modifiable Factors* |

N (%) |

|

Family caregiver related |

|

Transport problem |

15 (14) |

|

Female child |

5 (5) |

|

Delayed referral |

34 (32) |

|

Delay in illness recognition

|

45 (42) |

|

Maternal Ill-health |

4 (4) |

|

Quacks and faith healers |

11 (10) |

|

No family related issues |

30 (28) |

|

Medical personnel related |

|

Assessment |

|

|

Delayed detection |

5 (5) |

|

Alternative diagnosis not considered |

2 (2) |

|

Delay in specific management |

11 (11) |

|

Case monitoring |

20 (19) |

|

Case management |

|

|

Delayed referral |

1(5) |

|

Prescription error |

|

|

No medical personnel issues |

63 (59) |

|

Administrative factors |

|

Bed or ventilator unavailability |

57 (53) |

|

Lack of specialized care |

3 (3) |

|

Lack of equipment |

12 (11) |

|

Lack of medical personnel |

|

|

Communication problems |

1

|

|

Lack of drugs and blood products etc |

2 |

|

Lack of policy |

1 |

|

*More than one modifiable factor were present in some study

subjects; #Lack of medical personnel was a constant feature

throughout the study. |

Discussion

Pneumonia, CNS infections and diarrhea were main

causes of disease-related mortality and administrative issues followed

by family-related reasons were most common modifiable factors in our

study.

Our study results were in accordance with national

and global estimates of child mortality [1-6] and national audit

reports, evaluating modifiable factors, published from South Africa

[7-9]. We found a considerable proportion of deaths due to CNS

infections and tuberculosis in our study, which is expected because of

the referral hospital setting.

Although administrative issues were present

universally, majority of them are related to the infrastructure,

availability of healthcare personnel and equipments. These factors,

though modifiable, are related to health resource allocation and budget

constraints. However, a few administrative factors e.g. availability of

drugs, and unit policy decisions can be locally modified. There was a

high incidence of monitoring issues which is linked to the poor doctor:

patient (1:40-1:70)/nurse: patient (1:20-1:30) ratio, with bed occupancy

>100% during study period.

We acknowledge the limited sample size of our study

and mixed retrospective-prospective study design. However, our study

population was both rural and urban including slums, thereby giving an

insight to deaths occurring in all sections of society.

Family-related factors were present in more than

two-third of child deaths. Largely, children who died were very sick at

admission, which underscores the importance of early health seeking.

Majority of our population were daily wagers with poor literacy

levels, which could contribute to delayed illness recognition.

References

1. The latest estimates on child mortality generated

by the UN Inter-agency Group on Child Mortality Estimation (IGME):

Levels and Trends in Child Mortality, Report 2012 (13 September 2012).

http://www.childinfo.org/mortality.html. Accessed on 14 January, 2013.

2. Million Death Study Collaborators, Bassani DG,

Kumar R, Awasthi S, Morris SK, Paul VK, Shet A, et al. Causes of

neonatal and child mortality in India: a nationally representative

mortality survey. Lancet. 2010;376:1853-60.

3. Black RE, Cousens S, Johnson HL, Lawn JE, Rudan I,

Bassani DG, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child

mortality in 2008: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:1969-87.

4. Black RE, Morris SS, Bryce J. Where and why are 10

million children dying every year? Lancet. 2003;361: 2226-34.

5. Jones G, Steketee RW, Black RE, Bhutta ZA, Morris

SS; Bellagio Child Survival Study Group. How many child deaths can we

prevent this year? Lancet. 2003;362: 65-71.

6. Million Death Study Collaborators, Morris SK,

Bassani DG, Awasthi S, Kumar R, Shet A, Suraweera W, et al.

Diarrhea, pneumonia, and infectious disease mortality in children aged 5

to 14 years in India. PLoS One. 2011;6: e20119.

7. Krug A, Patrick M, Pattinson RC, Stephen C.

Childhood death auditing to improve paediatric care. Acta Paediatr.

2006;95:1467-73.

8. Krug A, Pattinson RC, Power DJ. Saving children -

an audit system to assess under-5 health care. S Afr Med J.

2004;94:198-202.

9. Pattinson, RC. Practical application of data

obtained from a Perinatal Problem Identification Programme. S Afr Med J.

1995;85:131-2.

10. Kleinman ME, Chameides L, Schexnayder SM, Samson

RA, Hazinski MF, Atkins DL, et al. Part 14: Pediatric Advanced

Life Support: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for

Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care.

Circulation. 2010:122: S876-908.

11. Kleinman ME, de Caen AR, Chameides L, Atkins DL,

Berg RA, Berg MD, et al. Part 10: Pediatric Basic and Advanced

Life Support: 2010 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary

Resuscitation and Emergency Cardio-vascular Care Science with Treatment

Recommendations. Circulation. 2010;122:S466-515.

|

|

|

|

|