|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2014;51:

27-31 |

|

Prevalence of Rotavirus Diarrhea among

Hospitalized Under-five Children

|

|

MA Mathew, Abraham Paulose, S Chitralekha, *MKC Nair,

†Gagandeep Kang and

‡Paul Kilgore

From Department of Pediatrics, Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church

Medical College Hospital, Kolenchery, Ernakulam District, Kerala; †Department

of Microbiology, Christian Medical College, Vellore, India and ‡Division

of Translational Research, International Vaccine Institute, Seoul, South

Korea.

Correspondence to: Dr MA Mathew, Professor, Department of Pediatrics,

Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church Medical College Hospital, Kolenchery,

Ernakulam District, Kerala 682 311, India.

Email: [email protected]

Received: February 02, 2013;

Initial review: March 05, 2013;

Accepted: August 22, 2013.

Published online: September 05, 2013.

PII: S097475591300111

|

Objectives: To estimate the prevalence of rotavirus diarrhea among

hospitalized children less than 5 years of age in Kerala State and to

determine the circulating strains of rotavirus in Kerala.

Design: Multicenter, cross-sectional study.

Setting: Eight representative hospitals in

Kunnathunadu Thaluk, Ernakulam district, Kerala.

Participants: Children in the age group under 5

years

Methods: Hospitalized children admitted with

acute diarrhea were examined and standardized case report form was used

to collect demographic, clinical and health outcome. Stool specimens

were collected and ELISA testing was done. ELISA rotavirus positive

samples were tested by reverse transcription PCR for G and P typing (CMC

Vellore).

Results: Among the 1827 children, 648 (35.9%)

were positive for rotavirus by the Rotaclone ELISA test. The prevalence

of rotavirus diarrhea in infants less than 6 months of age was 24.7%; 6-

11 months 31.9%; 12- 23 months 41.9%; 24- 35 months 46.9%; and 33.3% in

36- 59 months. Rotavirus infections were most common during the dry

months from January through May. G1P[8] (49.7%) was the most common

strain identified followed by G9P[8] (26.4%), G2P[4] (5.5%), G9P[4]

(2.6%) and G12P[6] (1.3%).

Conclusions: The prevalence of rotavirus diarrhea

among hospitalized children less than 5 years is high in Ernakulam

district, Kerala State.

Keywords: Kerala, Rotavirus diarrhea, Rotavirus infections.

|

|

R

otavirus is a leading cause of severe acute

gastroenteritis requiring hospitalization among infants and young

children worldwide [1]. Data on rotavirus disease burden are needed

across India to support credible, evidence-based decisions regarding any

intervention. There is a lack of nationally representative data on the

incidence of severe rotavirus disease in India [2]. Previous studies in

the Indian Rotavirus Strain Surveillance Network have confirmed that

rotavirus accounts for 39% of acute diarrheal hospitalizations [3].

There is a need for additional research and public health surveillance

to ensure that adequate information about rotavirus is obtained from

diverse populations in India.

There are limited data on rotavirus disease burden

among children in Kerala. We conducted a systematic study of rotavirus

diarrhea among children in Ernakulam district, Kerala with the

objectives to estimate the prevalence of diarrhea due to rotavirus among

hospitalized children younger than 5 years of age and also to describe

the circulating strains of rotavirus in this population.

Methods

This was a multicenter study conducted in 8 hospitals

in Kunnathunadu Thaluk, Ernakulam district, Kerala. In 2001 national

census, Kunnathunadu had 47,743 children less than 5 years of age. For

this study the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church Medical College (MOSC),

a tertiary care referral hospital, was the base hospital and 2

government and 5 private hospitals were selected.

All children aged <5 years who presented to a study

hospital with acute watery diarrhea and required hospitalization were

enrolled after informed consent was obtained from the parent or

guardian. The study was conducted over a period of 24 months between

February 1, 2009 and January 31, 2011.

A case of diarrhea was defined as increased stool

frequency compared with the usual pattern occurring in a child less than

5 years old for whom parents sought care for treatment of diarrhea. The

indications for hospitalization were (i) severe dehydration

requiring intravenous hydration, (ii) malnourished children with

dehydration, (iii) toxic appearance, changing mental status or

seizure, (iv) fever >38.5°C for infants <6 months or >39°C for 6-

36 months, (v) high output diarrhea ( >10 large volume

stool/day), (vi) persistent vomiting or diminished or no oral

intake, (vii) suboptimal or no response to ORT or further

deterioration, (viii) inability of the caregiver to administer

ORS, (ix) suspected surgical cause, and (x) history of

premature birth, chronic medical conditions or concurrent illness [4,5].

Hospitalized children less than 5 years of age

admitted with acute diarrhea were examined by trained medical staff. The

subject’s parent or guardian was interviewed concerning date of onset of

diarrhea and on vomiting and fever. Information was collected on the

duration of diarrhea, maximum number of stools passed per day, duration

and frequency of vomiting, degree of fever, presence and severity of

dehydration, and treatment. The severity of dehydration was assessed

according to the WHO Integrated Management of Childhood Illness Model

Handbook guidelines and was categorized into severe, some or no

dehydration [5]. Data concerning primary method of feeding and duration

of exclusive breast feeding were collected.

A standardized case report form based on the WHO

generic protocol [6] was used to collect demographic, clinical and

health outcome data.

Stool collection and laboratory analysis: Stool

specimens were collected from hospitalized patients and stored in the

refrigerator at 4°C and later transported to the base hospital in icebox

and stored at -20°C in the testing laboratory. ELISA testing (RotaClone,

Meridian diagnostics, Cincinnati,OH) was done twice weekly for detection

of rotavirus antigen. The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was highly

sensitive (100%) and specific (97%) for rotavirus antigen. ELISA

Rotavirus-positive samples were analyzed by reverse

transcription-polymerase chain reaction for G and P typing at Christian

Medical College, by previously reported methods [7].

Data management and statistical analysis: Data

were entered on a weekly basis into database management software, which

was created for the surveillance system and was based on an MS Visual

FoxPro platform. Analysis was performed using SAS software. Tests of

proportion were applied. A P value <0.05 was considered to be

statistically significant.

The protocol was reviewed and approved by the local

independent ethics committee/ institutional review board for each

participating centre.

Results

1827 children with diarrhea were admitted to study

health facilities and had a stool specimen collected for rotavirus

testing during the study period. There were 20 children just above five

years of age; they were excluded from final analysis (n=1807). Of

the 1807 stool specimens tested, 648 (35.8%) were positive for rotavirus

by the RotaClone ELISA test (Table I). The mean (SD) age

of children was 17.9 (13.8) months; male 17.2 (13.7) vs. female

18.8 (13.9).

TABLE I Rotavirus Results of Children With Diarrhea, Kerala, India, January 2009 to January 2011

|

RV-Positive (n= 648)

|

|

Age group (mo) |

|

|

<6 (n=235) |

58 (24.7%)

|

|

6-11 (n=568) |

181 (31.9%)

|

|

12-23 (n=535) |

233 (41.9%)

|

|

24-35 (n=194) |

91 (46.9%)

|

|

36-59 (n=255) |

85 (33.3%)

|

|

Fever group (°C)* |

|

|

≤ 37.5 (n=935) |

307 (32.8%)

|

|

37.6 -38.6 (n=690) |

256 (37.1%)

|

|

≥ 38.7 (n=182) |

85 (46.7%)

|

|

Length of stay (days)* |

|

|

≤ 2 (n=858) |

300 (34.9%)

|

|

3- 6 (n=779) |

267 (34.3%)

|

|

≥ 7 (n=170) |

81 (47.6%)

|

|

Dehydration# |

|

|

None (n =1292)

|

416 (32.2%)

|

|

Some (n =503) |

228 (45.3%)

|

|

Severe (n =9) |

4 (44.4%)

|

|

*P<0.01; #P<0.001. |

|

|

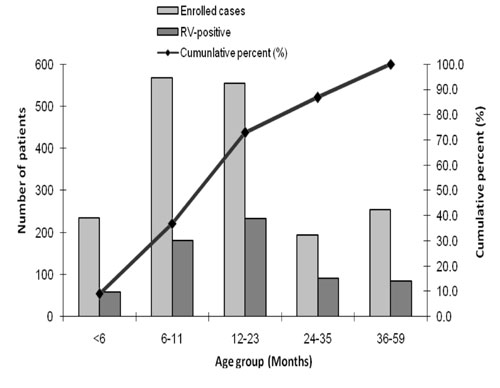

Fig. 1 Age distribution of children

with diarrhea, Kerala, India, February 2009 to January 2011.

|

|

|

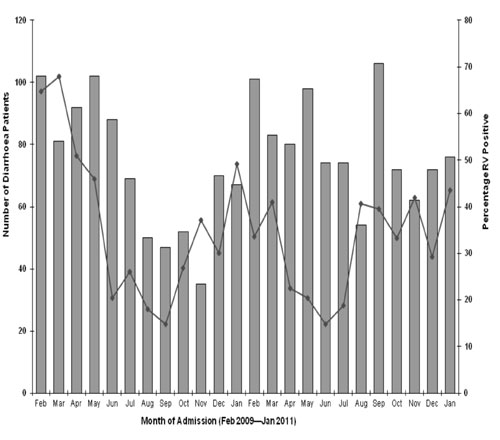

Fig. 2 Monthly distribution of

rotavirus-positive patients, Kerala, India, February 2009 –

January 2011 (n= 1807).

|

Fig. 1 shows the cumulative age distribution

of rotavirus cases. There was no mortality in the study population.

Rotavirus infections were seen throughout the year and were most common

during the hot dry months from January through May (Fig. 2).

Of the 648 samples that were ELISA rotavirus positive, genotyping (Table

II) was done for 450 (81.6%) randomly selected samples. The majority

(49.7%) of rotavirus strains typed were G1P[8] strains. An additional 12

(2.6%) samples were untypable.

TABLE II Distribution Of G And P Types Among A Randomly Selected Subset (N=450)

Of Rotavirus Positive Samples

Genotype

(n=450) |

Number

|

|

G1 P[8] |

224 ( 49.7%) |

|

G9 P[8] |

119 (26.4 %) |

|

G2 P[4] |

25 (5.5%)

|

|

G9 P[4] |

12 (2.6%) |

|

G12 P[6] |

6 (1.3%) |

|

G1 P[6] |

4 (0.8%) |

|

G12 P[8] |

4 (0.8%) |

|

G1 P[4] |

1 (0.2%) |

|

G1 P[Untypable] |

2 (0.4%) |

|

G9 P[Untypable] |

11 (2.4%) |

|

Partially typed |

6 (1.3%) |

|

Mixed infections |

24 (5.3%) |

|

Both G and P untypable |

12 (2.6%) |

Discussion

This is the first systematic study to assess the

prevalence of rotavirus diarrhea among children younger than 5 years of

age in Kerala. In this study, rotavirus was detected in 35.9% of

diarrhea-related hospital admissions among children less than 5 years of

age in Ernakulam district, Kerala.

A review of studies performed in India during 1990-

2005 had estimated that rotavirus disease accounted for 20.8% of all

diarrhea- related hospital admissions [7]. The Indian Rotavirus Strain

Surveillance Network carried out a multi-centric study in seven

different regions of India and reported that rotavirus was detected in

stools of 39% children aged <5 years [3]. Inclusion of children at

hospitals caring for lower acuity diarrheal episodes or less severe

disease may account for a lower percentage of rotavirus positive cases

among the total number of enrolled patients in our study compared with

previous studies [3,8-15].

The prevalence of rotavirus diarrhea in infants aged

<6 months was 24.7%, with high prevalence in children aged 6 months to

11 months and 12-23 months (31.9% and 41.9%, respectively). These data

are important because they demonstrate that the vast majority of cases

could be prevented by an effective rotavirus vaccine given to children

along with their primary immunization series. But for a setting in a

developing country, this is somewhat lower than expected since ~80% to

85% of all rotavirus cases in children under 5 years occurred by 18

months of age in hospital-based studies [16]. These observations may

indicate that the epidemiology of rotavirus in Kerala may differ from

other parts of India, because general living conditions and

socio-economic status are better in Kerala.

A marked seasonality was not seen in our study and

rotavirus infections peaked from January through May and were less

common during the monsoon season months of June through September.

Rotavirus is markedly seasonal in Northern temperate locations but was

less seasonal in Southern locations with a tropical climate

[3,10,17,18]. It has been observed that with minimal seasonality,

rotaviruses circulate at a relatively higher level all year round,

resulting in children being exposed at an early age and experiencing

severe illness [14].

This is the first study in Kerala to provide

information on both rotavirus G and P types. The results of G and P

typing shows that the G1P[8] strain is the most common contributing half

the number of cases. This finding is also consistent with the results

from national rotavirus surveillance in India showing that the G1P[8]

strain was among the two most common strains from December 2005 to

November 2007. However, there were differences in that the G9P[8] strain

is the second most common strain found in the Kerala field site and 5.5%

of strains were G2P[4], while overall in the national Indian

surveillance network the G2P[4] and G9 P[8] strains accounted for 25.7%

and 8.5%, respectively of all rotavirus strains [3]. A recent study from

Vellore reported that the most common types were G1P[8] (in 15.9% of

infections), G2P[4] (in 13.6%), G10P[11] (in 8.7%), G9P[8] (in 7.2%),

G1P[4] (in 4.4%), G10P[4] (in 1.7%), G9P[4] (in 1.5%), G12P[6] (in

1.1%), and G1P[6] (in 0.6%) [19]. The proportion of untypable strains

may suggest the potential for emergence of new rotavirus strains in

Kerala.

The strengths of this study include the use of the

WHO generic protocol and laboratory confirmation of rotavirus diarrhea

in a single reference laboratory including genotyping of rotavirus

strains. Potential limitations are the small study population and the

lack of ability to extrapolate disease burden to milder disease because

this was a hospital-based study.

In conclusion, this study highlights that rotavirus

diarrhea accounts for a large proportion of diarrheal disease in

hospitalized children less than 5 years in Ernakulam district in Kerala.

Contributors: MAM: conceived and designed the

study and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. He

will act as guarantor of the study; AP: collected data and drafted the

paper; MKC, GK and SC: did final revision of manuscript. GK conducted

the laboratory tests, and interpreted them; PK: analysed the data and

helped in manuscript writing. The final manuscript was approved by all

authors.

Funding: Indian Council for Medical Research, New

Delhi; Competing interests: None stated.

|

What Is Already Known?

•

Rotavirus is the leading cause of severe diarrhea in Indian

children less than 5 years.

What This Study Adds?

• High prevalence of rotaviral diarrhea in

Ernakulam, Kerala state, accounting for 35.9% of diarrhea-related

hospitalizations among children less than 5 years of age.

|

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Rotavirus surveillance- worldwide, 2001- 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly

Rep. 2008;57:1255-7.

2. Khan G, Fitzwater S, Tate JE, Kang G, Ganguly N,

Nair G, et al. Epidemiology and prospects for prevention of rotavirus

disease in India. Indian Pediatr. 2012;49:467-74.

3. Kang G, Arora R, Chitambar SD, Deshpande J, Gupte

MD, Kulkarni M, et al. Multicenter, hospital-based surveillance of

rotavirus disease and strains among Indian children aged <5 years. J

Infect Dis. 2009;200:S147-53.

4. Bhatnagar S, Lodha R, Choudhary P, Sachdev HP,

Shah N, Narayan S, et al. Consensus statement of IAP National Task

Force: Status report on management of acute diarrhea. Indian Pediatr.

2007;44: 380-9.

5. World Health Organization. The Treatment of

Diarrhea: A Manual for Physicians and Other Senior Health Workers, 4th

ed. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2005

(http://www.who.int/child-adolescent health/New_Publications/CHILD_HEALTH/ISBN_92_4_159318_0.pdf).

Accessed on May 12, 2013.

6. Bresee J, Parashar U, Holman R, Gentsch J, Glass

R. Generic protocols for (i) hospital-based surveillance to estimate the

burden of rotavirus gastroenteritis in children and (ii) a

community-based survey on utilization of health care services for

gastroenteritis in children. Document WHO/V&B/02.15.Geneva: World Health

Organization, 2002:1-67.

7. Ramani S, Kang G. Burden of disease and molecular

epidemiology of group A rotavirus infections in India. Indian J Med Res.

2007;125:619-32.

8. Samajdar S, Ghosh S, Chawla- Sarkar M, Mitra U,

Dutta P, Kobayashi N, et al. Increase in prevalence of human group A

rotavirus G9 strains as an important VP7 genotype among children in

eastern India. J Clin Virol. 2008;43:334-9.

9. Bahl R, Ray P, Subodh S, Shambharkar P, Saxena M,

Parashar U, et al. Incidence of severe rotavirus diarrhoea in New Delhi,

India, and G and P types of the infecting rotavirus strains. J Infect

Dis. 2005;192:S114-9.

10. Saravanan P, Ananthan S, Ananthasubramanian M.

Rotavirus infection among infants and young children in Chennai, South

India. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2004;22:212-21.

11. Kang G, Green J, Gallimore CI, Brown DW.

Molecular epidemiology of rotaviral infection in South Indian children

with acute diarrhoea from 1995-1996 to 1998-1999. J Med Virol.

2002;67:101-5.

12. Banerjee I, Ramani S, Primrose B, Moses P,

Iturriza- Gomera M, Gray JJ, et al. Comparative study of the

epidemiology of rotavirus in children from a community-based cohort and

a hospital in South India. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:2468-74.

13. Kelkar Sd, Purohit SG, Simha KV. Prevalence of

rotavirus diarrhoea among hospitalized children in Pune, India. Indian J

Med Res.1999:109:131-5.

14. Mishra V, Awasthi S, Nag VL, Tandon R. Genomic

diversity of group A rotavirus strains in patients aged 1-36 months

admitted for acute watery diarrhoea in northern India: a hospital based

study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16;45-50.

15. Chakravarti A, Chauhan MS, Sharma A, Verma V.

Distribution of human rotavirus G and P genotypes in a hospital setting

from Northern India. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health.

2010;41:1145-52.

16. Nelson EA, Bresee JS, Parashar UD, Widdowson MA,

Glass RI. Rotavirus epidemiology: the Asian Rotavirus Surveillance

Network. Vaccine. 2008;26:3192-6.

17. Ray P, Sharma S, Agarwal RK, Longmei K, Gentsch

Jr, Paul VK, et al. First detection of G12 rotavirus in newborns with

neonatal rotavirus infection at All India Institute of Medical Sciences,

New Delhi, India. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:3824-7.

18. Phukan AC, Patgiri DK, Mahanta J. Rotavirus

associated acute diarrhoea in hospitalized children in Dibrugarh, Nort-east

India. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2003;46:274-8.

19. Gladstone BP, Ramani S, Mukhopadhya I, Muliyil J,

Sarkar R, Rehman AM, et al. Protective effect of natural rotavirus

infection in an Indian birth cohort. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:337-46.

|

|

|

|

|