|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2011;48: 969-971 |

|

Azathioprine Hypersensitivity Presenting as

Sweet Syndrome in a Child with Ulcerative Colitis |

|

Mi Jin Kim, *Kee Taek Jang, and Yon Ho Choe

From the Departments of Pediatrics and *Pathology,

Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul,

Korea.

Correspondence to: Yon Ho Choe, Department of

Pediatrics, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of

Medicine, 50 Irwon-dong, Gangnam-gu, Seoul, 135-710, South Korea.

Email: [email protected]

Received: June 10, 2010;

Initial Review: July 01, 2010;

Accepted: August 05, 2010.

|

Sweet syndrome is a cutaneous lesion characterized by tender, red

inflammatory nodules or papules. We describe a pediatric case of Sweet

syndrome presenting 10 days after treatment with azathioprine. As

azathioprine is widely used in children with inflammatory bowel disease,

clinicians should be aware of this unusual adverse reaction.

Key words: Azathioprine, Children, Hypersensitivity, Sweet

syndrome.

|

|

Sweet syndrome, or acute febrile neutrophilic

dermatosis, is a cutaneous lesion characterized by tender, red

inflammatory nodules or papules, usually affecting the upper limbs,

face and neck. It can become generalized, and patients often are ill

with associated signs and symptoms, including malaise, high fever,

neutrophilia, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive

protein levels, which mimic an infectious process. It has rarely been

seen as a mani-festation of azathioprine hypersensitivity in adults

[1-4].

Case Report

A nine-year-old girl was referred for management

of refractory ulcerative Colitis (UC) that had been diagnosed one

year previously. She had no history of reported drug allergies and

had been prednisolone-dependent (2 mg/kg/day) for much of the

preceding year, with her disease flaring after attempts to reduce the

prednisolone dosage. During the hospitalization, she received

mesalazine treatment (48 mg/kg/day) without prednisolone, but it was

ineffective. She underwent azathioprine therapy (1 mg/kg/day) and 10

days later was hospitalized for fever (temperature of 39.2ºC), skin

rash and hematochezia.

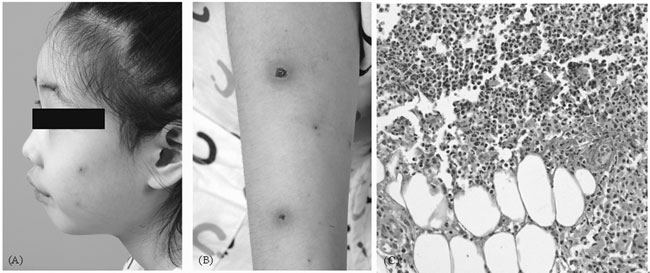

Physical examination was significant for numerous

erythematous, painful, 1-3 mm vesicular lesions with central pustules

on her face and both arms (Fig. 1). Laboratory results

showed an elevated white blood cell count (13,470/µL) with

neutrophilia, microcytic hypochromic anemia (hemoglobin 9.2 g/dL, MCV

80.9 fl, MCH 24.8 pg), hyponatremia (132 mmol/L), and a markedly

raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate (89 mm/hr) and C-reactive

protein level (3.13mg/dL). Anti-nuclear antibody was negative, but

c-type anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (c-ANCA) was positive.

Her thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) activity was normal (18.2

U/ml RBC, reference range: 15.1-26.4 U/mL RBC). Blood cultures and

urinalysis were obtained and the patient was started on cefotaxime

(100 mg/kg/day) for a possible infectious etiology.

|

|

Fig. 1 Pustular and crust lesions

surrounded by erythema appeared on face (a) and arm (b) 10 days

after administration of azathioprine. (c) Skin biopsy of

pustular lesion shows massive neutrophilic infiltration in

entire dermis (H&E, x400). |

Two days after the cefotaxime treatment, the

patient still had a fever. The patient then received metronidazole

(30 mg/kg/day) for a week and prednisone (1.7 mg/kg/day). However,

she was febrile with shaking chills and nausea. Cultures taken from

blood and urine prior to antibiotic therapy were sterile. Biopsy

specimens and tissue cultures were taken from the pustular lesions.

Pathologic evaluation of skin biopsy showed massive neutrophilic

infiltrate in the entire dermis (Fig. 1). Tissue

culture results were negative for bacterial or fungal infection.

Based on the clinical course, a diagnosis of sweet syndrome was made.

As the patient’s fever had not subsided in spite of the

administration of antibiotics and steroid, we presumed that the sweet

syndrome was caused by the azathioprine and was not due to

inflammatory bowel disease. The azathioprine therapy was

discontinued. Within 48 hours, the patient’s fever abated and her

skin lesions improved. Following this improvement, the prednisolone

dose was reduced to 0.4 mg/kg per day without a recurrence of her

symptoms.

At follow-up after two weeks, there had been no

recurrences of her symptoms, and her UC was comparatively well

controlled by prednisolone and mesalazine treatment.

Discussion

The criteria for drug-induced SS have been

reviewed by many authors [3,5] and include abrupt onset of painful

erythematous plaques or nodules, histopathologic evidence of a dense

neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of leukocytoclastic

vasculitis, pyrexia (temperature >38ºC), and a temporal relationship

between drug ingestion and clinical presentation, as well as

resolution after withdrawal. Our patient meets most of these

criteria.

ANCAs have been described in some cases, and may

be pathogenically relevant through the activation of neutrophils [6].

In our case, c-ANCA was positive. Kemmett, et al. [7] reported

the presence of c-ANCA in six of the seven patients with sweet

syndrome and speculated whether ANCA may be helpful in establishing

the diagnosis of sweet syndrome .

Azathioprine is a widely used immunosuppressive

agent that has been used increasingly as a steroid-sparing agent for

the treatment of Crohn’s disease and UC. Azathioprine rarely causes a

hypersensitivity syndrome which is characterized by fever, headache,

arthralgias, and rash, with possible cardiovascular, renal, lung, and

hepatic involvement [8]. Skin lesions include erythematous or

maculopapular eruptions, vesicules or pustules, urticaria, purpuric

lesions, erythema multiforme, or erythema nodosum. A case of acute

generalized exantematous pustules induced by azathioprine like our

case also has been reported [9]. Diagnosis is often missed or

delayed, as the clinical features are often misinterpreted as either

sepsis or an exacerbation of the underlying disease state. According

to previous studies [10], TPMT activity was not predictive of this

type of adverse effect.

The morphology of these skin lesions can mimic

that of several other mucocutaneous and systemic conditions. The

differential diagnosis includes infectious and inflammatory

disorders, neoplastic conditions, reactive erythemas, vasculitis.

Skin lesions and negative cultures help in the diagnosis. In

addition, negative test results for autoimmune diseases are important

for diagnosis. In our case, an infection focus or signs of an

autoimmune disease could not be detected. Clinical and

histopathologic findings supported the drug-induced sweet syndrome

and cessation of the drug caused a rapid regression in symptoms. In

patients without prior exposure to azathioprine, signs and symptoms

usually begin approximately two weeks from the initial azathioprine

exposure [1], which began after 10 days in this child.

We believe that azathioprine-induced sweet

syndrome may be under-diagnosed because it can easily be

misinterpreted as inflammatory bowel disease-related skin changes.

Contributors: All authors contributed to case

work-up and drafting the manuscript.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None stated.

References

1. Garey KW, Streetman DS, Rainish MC.

Azathioprine hypersensitivity reaction in a patient with ulcerative

colitis. Ann Pharmacother. 1998;32:425-8.

2. Paoluzi OA, Crispino P, Amantea A, Pica R,

Iacopini F, Consolazio A, et al. Diffuse febrile dermatosis in

a patient with active ulcerative colitis under treatment with

steroids and azathioprine: a case of Sweet’s syndrome. Case report

and review of literature. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36:361-6.

3. El-Azhary RA, Brunner KL, Gibson LE. Sweet

syndrome as a manifestation of azathioprine hypersensitivity. Mayo

Clin Proc. 2008;83:1026-30.

4. Yiasemides E, Thom G. Azathioprine

hypersensitivity presenting as a neutrophilic dermatosis in a man

with ulcerative colitis. Australas J Dermatol. 2009;50:48-51.

5. Su WP, Liu HN. Diagnostic criteria for Sweet’s

syndrome. Cutis. 1986;37:167-74.

6. Sarkany RP, Burrows NP, Grant JW, Pye RJ,

Norris PG. The pustular eruption of ulcerative colitis: a variant of

Sweet’s syndrome? Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:365-6.

7. Kemmett D, Harrison DJ, Hunter JA. Antibodies

to neutrophil cytoplasmic antigens: serologic marker for Sweet’s

syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24: 967-9.

8. El-Azhary RA. Azathioprine: current status and

future considerations. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:335-41.

9. Elston GE, Johnston GA, Mortimer NJ, Harman KE.

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis associated with

azathioprine hypersensitivity. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:52-3.

10. McGovern DP, Travis SP, Duley J,

Shobowale-Bakre el M, Dalton HR. Azathioprine intolerance in patients

with IBD may be imidazole-related and is independent of TPMT

activity. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:838-9.

|

|

|

|

|