|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2014;51:

309-310 |

|

Percutaneous Central Line Extravasation

Masquerading as an Abscess

|

|

Binu Govind, Prakash Ignace Tete and Niranjan Thomas

From Department of Neonatology, Christian Medical

College, Vellore , Tamil Nadu, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Niranjan Thomas, Professor,

Department of Neonatology, Christian Medical College Hospital, Vellore

632 004, Tamilnadu, India.

Email:

niranjan@cmcvellore.ac.in

Received: December 19, 2013;

Initial review: January 07, 2014;

Accepted: February 05, 2014.

|

|

Background: Percutaneous central line insertion is a common

procedure in the neonatal intensive care unit. Case characteristics:

A preterm baby, who had a percutaneous central line inserted developed

an erythematous swelling over the infraclavicular area. Observation:

A diagnosis of abscess was made, and an incision and drainage done that

revealed a white fluid with high triglyceride content, confirming lipid

extravasation. Outcome: The lesion healed completely few days

after removal of the catheter. Message: This case highlights the

importance of proper placement and confirmation of central line

position.

Keywords: Central venous line, Complication,

Abscess, Total parenteral nutrition.

|

|

Percutaneously inserted central catheters (PICC)

are commonly used in the neonatal intensive care units (NICU) to

administer hyperosmolar solutions, total parenteral nutrition (TPN) and

medications. However, PICCs have been associated with complications due

to displacement, embolism, thrombosis or infection of the catheter [1].

Effusions into a body cavity can occur when a PICC passes into a small

vein and damage the vascular wall occurs. Extravasation into pleural,

pericardial, subdural and retroperitoneal, and renal pelvis have been

described. [2-4] Central line migration and extravasation leading to

superficial abscess is extremely rare [5]. We report a child who

presentedwith a chest wall swelling which was due to extravasation of a

malpositioned PICC into a superficial vein of the chest wall.

Case Report

The patient was the first of twins, born to a

primigravida mother who had regular antenatal care in our hospital. The

mother had spontaneous onset of labour at 29weeks of gestation and baby

was born by assisted breech delivery with a birthweight of 1280g and

APGAR scores of 2, 6 and 7 at 1, 5 and 10 minutes, respectively. He was

admitted into the NICU for preterm care and respiratory distress. He

received 70 hours of continuous positive airway pressure for moderate

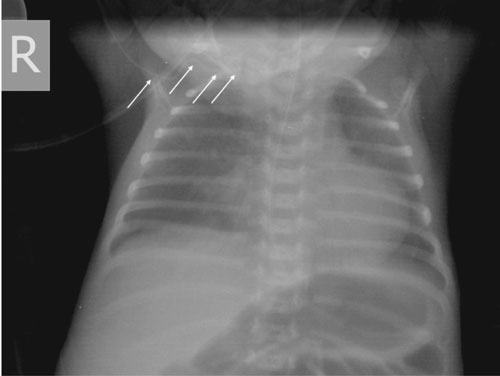

hyaline membrane disease, and antibiotics for presumed sepsis. A right

brachial PICC (Vygon, 2 Fr) was inserted and position was confirmed

radiologically to be in the subclavian vein (Fig. 1) and

TPN infusion was started. On day 27 of life, baby was noted to have an

erythematous swelling in the right infraclavicular region. Pediatric

surgery consultation was obtained, and incision and drainage was done in

view of a clinical diagnosis of abscess. A whitish coloured fluid was

seen draining out and on flushing the PICC line, a fluid similar in

appearance to lipid infusate was noted to be coming out (Fig.

2). Triglyceride estimation of the sample aspirated from the site

was high (756 mg/dL), confirming that the fluid was extravasating TPN.

The PICC line was removed and the drainage site started healing

gradually. He was discharged on day 66 of life on breast feeds when he

was gaining weight adequately. At follow-up of 18 months, the child is

neurodevelop-mentally normal.

|

|

|

Fig. 1 X-ray of the chest and abdomen

showing the position of the PICC appearing to be in the right

subclavian.

|

Fig. 2 Infraclavicular swelling with

extravasating intralipid after the incision and drainage.

|

Discussion

PICC is useful in the care and nutrition of sick and

small neonates, and is one of the common procedures done in the NICU.

The ideal position for catheters inserted through the upper limb is at

the junction of superior vena cava (SVC) and right atrium while those

inserted through the lower limb line should be in the inferior vena cava

(IVC) at the level of diaphragm [3,6]. Risks involved in the use of PICC

lines include infection, thrombosis, vessel perforation and

extravasations [1]. Factors implicated in causing the vessel perforation

and subsequent extravasation include occlusive mural thrombosis,

localized phlebitis and erosion of the vessel wall by the catheter. When

the end of the catheter creates an acute angle with the vessel wall, the

jet of abrasive fluid directed on the wall may lead to formation of a

thrombus attaching the catheter tip to the vessel endothelium [1]. This

is more likely to occur if the catheter is in a smaller vessel with a

slower flow of blood.

There have been reports of PICC extravasation causing

pericardial effusion and also leakage of fluid into subdural space,

renal pelvis, peritoneal cavity, retroperitoneal space and pleural space

[3,4]. Extravasations into soft tissue have been reported less

frequently. Baker, et al.[5] have described extravasation of a

lower limb PICC presenting as an abdominal wall abscess similar to the

presentation seen in our patient.

In our case, the initial position of the PICC was

thought to be in the subclavian vein but was probably malpositioned into

a superficial vein of the chest. This highlights the fact that optimal

position of the PICC should always be ensured. Blind positioning of PICC

based on anatomical landmarks and anthropometry leads to high

malposition rates [7]. Single plane X ray alone may not be adequate in

identifying the central line. In one series, 50% of line tips were not

identified by plain X-ray; radio-opaque contrast injection

increased detection rates to 93.5% [8]. Odd, et al.[9] showed

radio-opaque contrast to increase the proportion of central line tip

position identification from 39% to 55%. Groves, et al.[10] have

described easy localization of the PICC line tip using colour doppler

ultrasound with the line being flushed with saline at a rate of 0.1 mL/s.

To avoid complications, either contrast injection or bedside ultrasound

with colour doppler may be used to identify the central line tip

position. Confirmation of central line tip and daily inspection by

experienced personnel will help prevent delay in identification of

complications [1].

Contributors: All the authors were

involved in the diagnosis and management of the patient.

Funding: None; Competing interests: None

stated.

References

1. Menon G. Neonatal long lines. Arch Dis Child Fetal

Neonatal Ed. 2003;88:F260-2

2. Madhavi P, Jameson R, Robinson MJ. Unilateral

pleural effusion complicating central venous catheterization. Arch Dis

Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2000;82:F248-9.

3. Nowlen TT, Rosenthal GL, Johnson GL, Tom DJ, Vargo

TA. Pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade in infants with central

catheters. Pediatrics. 2002;110:137-42.

4. Nadroo AM, al-Sowailem AM. Extravasation of

parenteral alimentation fluid into the renal pelvis-a complication of

central venous catheter in a neonate. J Perinatol. 2001;21:465-6.

5. Baker J, Imong S. A rare complication of neonatal

central venous access. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2002;86:F61-2.

6. Ramasethu J. Complications of vascular catheters

in the neonatal intensive care unit. Clin Perinatol. 2008;35:199-222.

7. Johnston AJ, Bishop SM, Martin L, See TC, Streater

CT. Defining peripherally inserted central catheter tip position and an

evaluation of insertions in one unit. Anaesthesia. 2013;68:484-91.

8. Reece A, Ubhi T, Craig AR, Newell SJ. Positioning

long lines: contrast versus plain radiography. Arch Dis Child Fetal

Neonatal Ed. 2001;84:F129-130.

9. Odd DE, Page B, Battin MR, Harding JE. Does

radio-opaque contrast improve radiographic localization of percutaneous

central venous lines? Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2004;89:F41-43.

10. Groves AM, Kuschel CA, Battin MR. Neonatal long

lines: localisation with colour Doppler ultrasonography Arch. Dis Child

Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2005;90:F5.

|

|

|

|

|